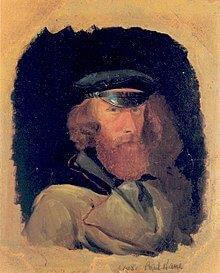

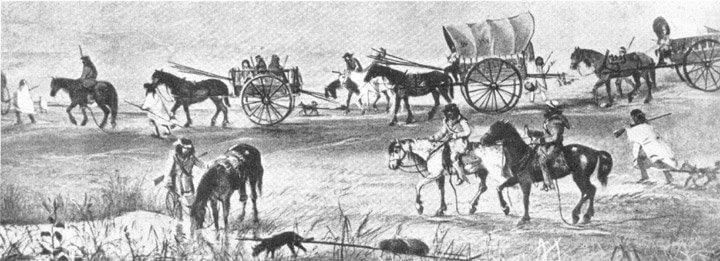

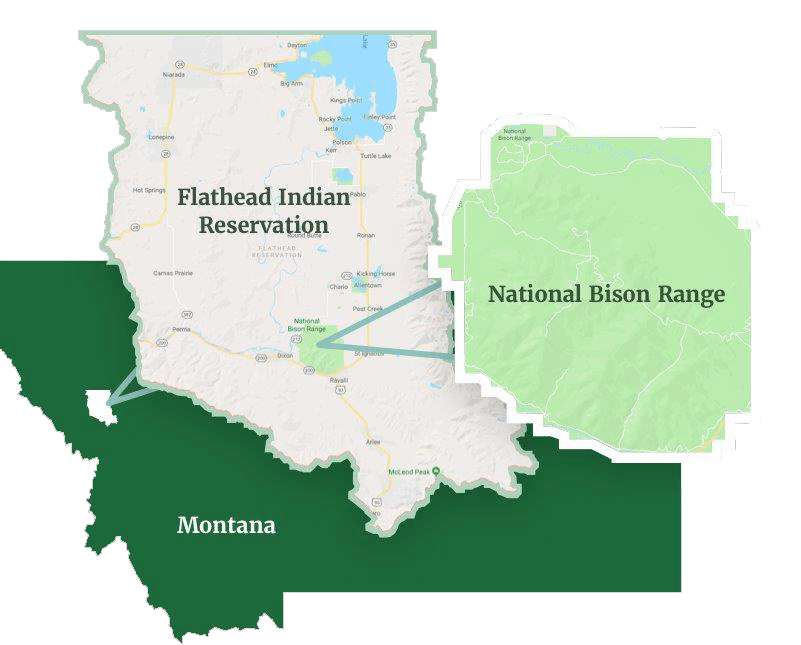

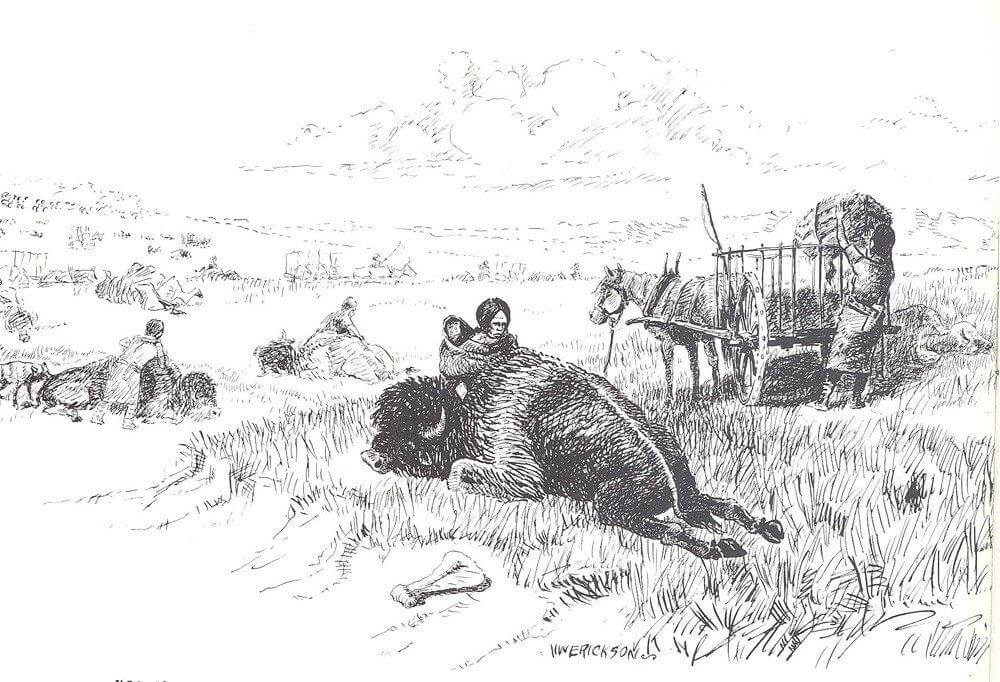

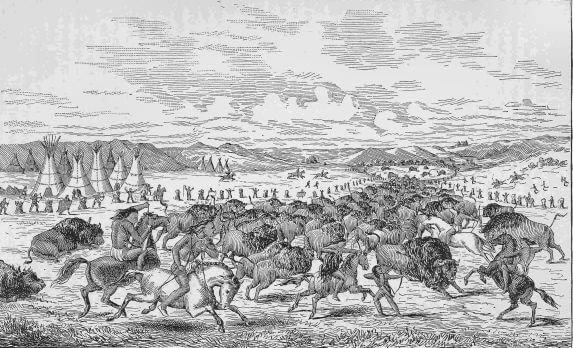

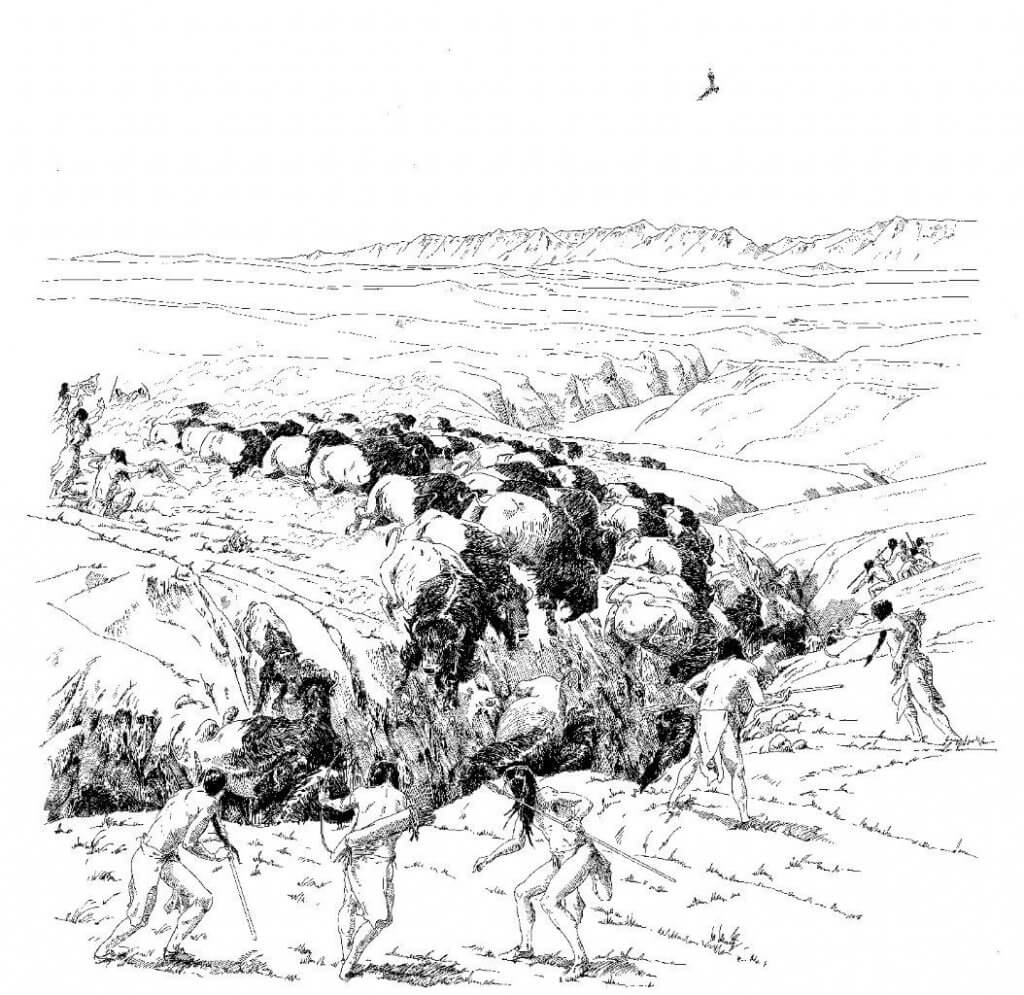

“Cree Indians impounding buffaloes.” An Impound often included drive lines leading down a hill into some kind of corral or enclosure. There the herd could be trapped and slaughtered. Prof HY Hind’s Red River, Assiniboine and Saskatchewan Expedit. Credit Wm Hornaday.

In rocky or wooded country, the hunters built strong enclosures of rocks and trees. These were used over and over in areas frequented by buffalo, successfully when the animals cooperated.

Old Weasel Tail described the impound method, thus:

“Near the edge of timber and toward the bottom of a downhill slope the Indians built a corral of wooden posts set upright in the ground to a height of about seven feet. They connected the posts by cross-poles tied in place with rawhide ropes.”

The downward slope was important—as were drive lines and wings bringing the Buffalo to the entrance.

“Around three sides of the corral they laid stakes over the lowest cross-poles. Their butt ends were firmly braced in the ground outside the corral. These stakes projected about three feet inside the corral at an angle, so their sharpened ends were about the height of a buffalo’s body.

“If the buffalo tried to break through the corral they would be impaled on these stakes.”

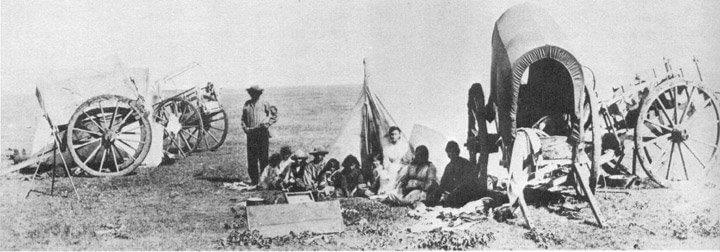

The hunters fired their weapons until all the buffalo in the corral were slaughtered, while women and children guarded any weak sections with waving robes and shouting.

The scene was bloody.

As one observer said, “The scene was more repulsive than pleasant or exciting. A great number were already killed and the live ones were tumbling about furiously over the dead bodies of their companions, and I hardly think the space would have held them all alive without some being on top of others, and in addition the bottom of the pound was strewn with fragments of carcasses left from former slaughters in the same place.”

And another: “People running frantically around the mound of animals trying to kill the wounded and yet avoid being killed. . . After firing their arrows they generally succeeded in extracting them again by a noose on the end of a pole, and some had even the pluck to jump into the area and pull them out with their hands—but if an old bull or a cow happened to observe them they had to be very active in getting out again.”

“Even mere boys and young girls”—were stationed on the walls of the corral—”all busy plying bows and arrows, guns and spears and even knives, to compass the destruction of the buffalo.

“Bison stumbling, rolling, dragging themselves from the pyramid.

“Animals of every age were huddled together in all the forced attitudes of violent death. Some lay on their backs with eyes starting from their heads and tongue thrust out through clotted gore. . . One little calf hung suspended on the horns of a bull which had impaled it in the wild race round and round the pound.”

Jack Brink in his book Imagining Head-Smashed-In recorded that every animal in the pound had to be killed, to enable the people to get to the meat. Also he said there was a spiritual belief that the buffalo now knew too much and if some escaped, would alert others and ensure the failure of future attempts.

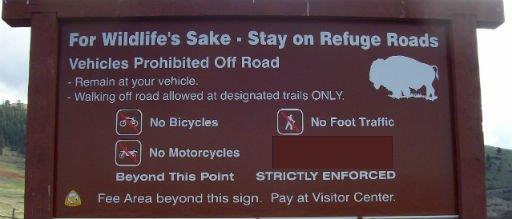

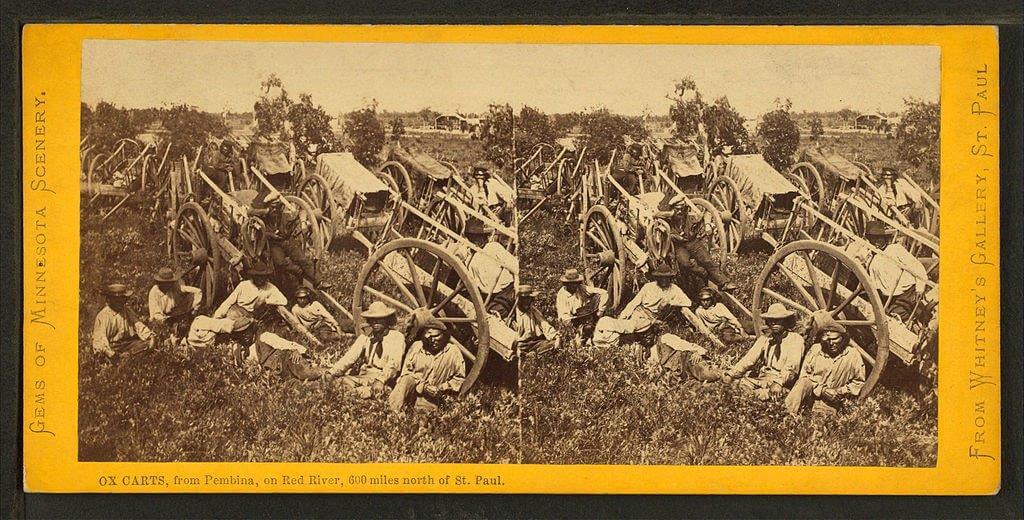

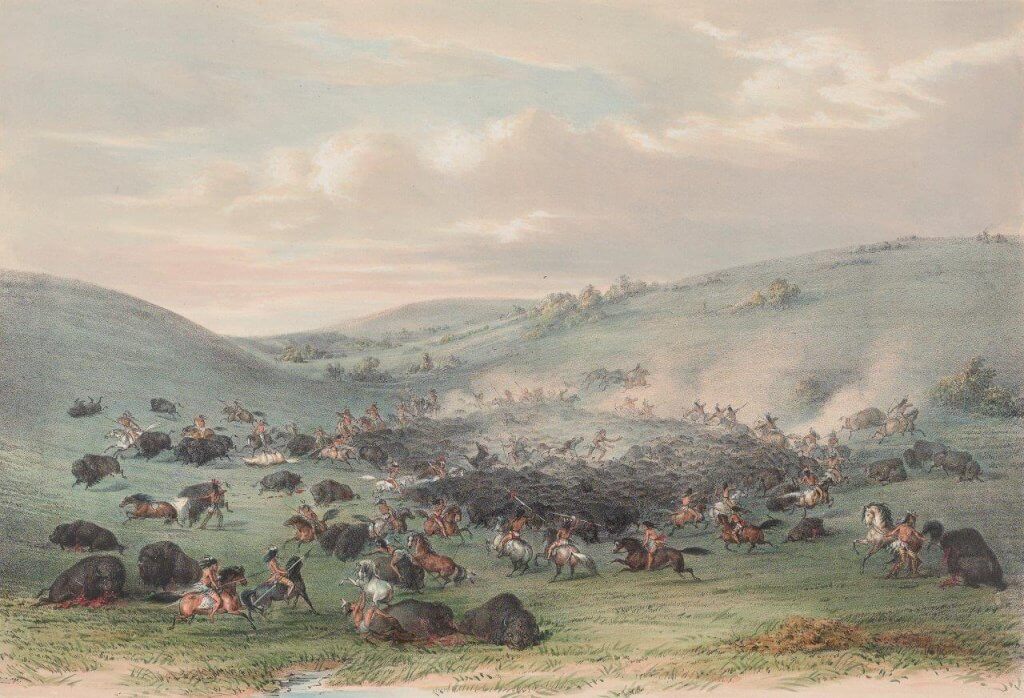

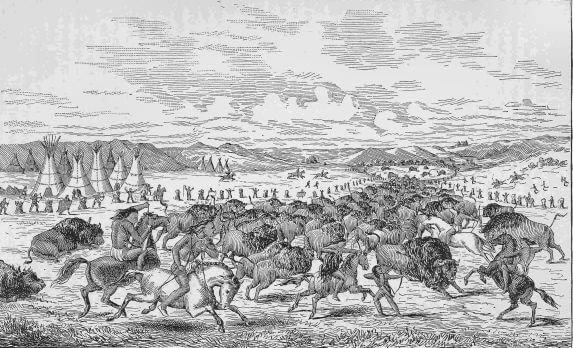

Drive Lines Critical in Moving Buffalo

With the development of the Impounding method of trapping buffalo, drive lines comparable to the often-complex drive lines of Buffalo Jumps began to take shape.

Old Weasel Tail explained how Drive Lines worked above the impoundment corral.

“From the open side of the corral the fence of poles extended into two wings outward and up the hill. These lines were further extended by piles of cut willows in the shape of conical lodges about half the height of a man, tied together at their tops. . . spaced at intervals of several feet.

“On the hill just above the corral opening a number of poles were placed on the ground crosswise of the slope and parallel to each other. The buffalo had to cross these poles to enter the corral. The poles were covered with manure and water, which froze and became slippery so that once the buffalo were in the corral they couldn’t escape by climbing back up the hill.

“Before the drive began, a beaver bundle owner removed the sacred buffalo stones from his bundle and prayed.

“He sang a song, ‘Give me one buffalo or more. Help me to fall the buffalo.’”

The hunters had numerous special rites, adds Brink, “Ceremonies and taboos associated with buffalo and the hunting of this animal. It is absolutely correct to state that everything about a buffalo hunt, from beginning to end, was steeped in spiritual beliefs and appropriate ceremony.”

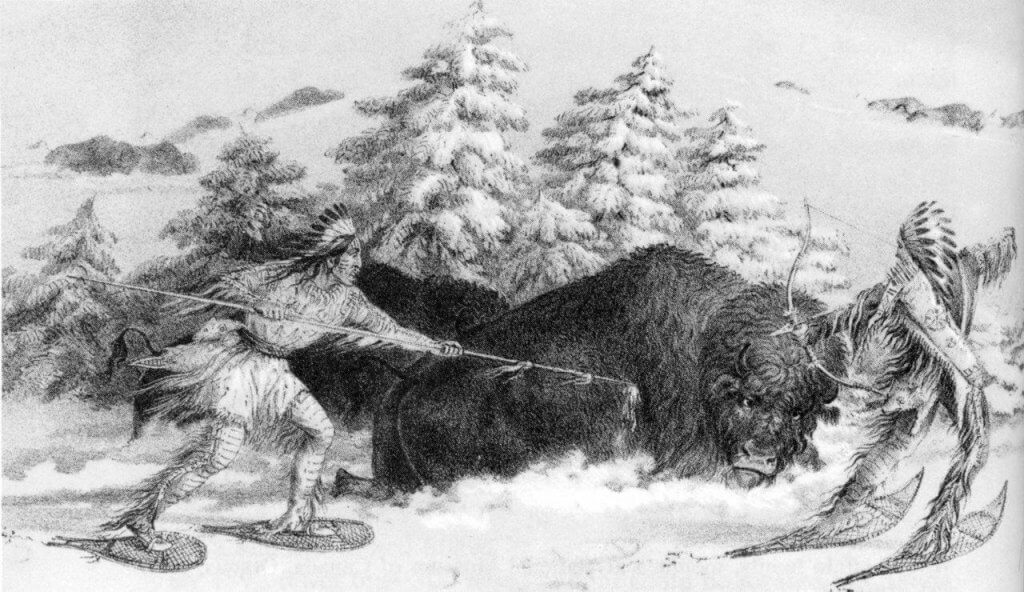

Buffalo have an excellent sense of smell and hearing. The wind brings both, and the ancient hunters clearly understood that.

Brink quotes one observer, who travelling through vast herds of buffalo one day in 1820, wrote:

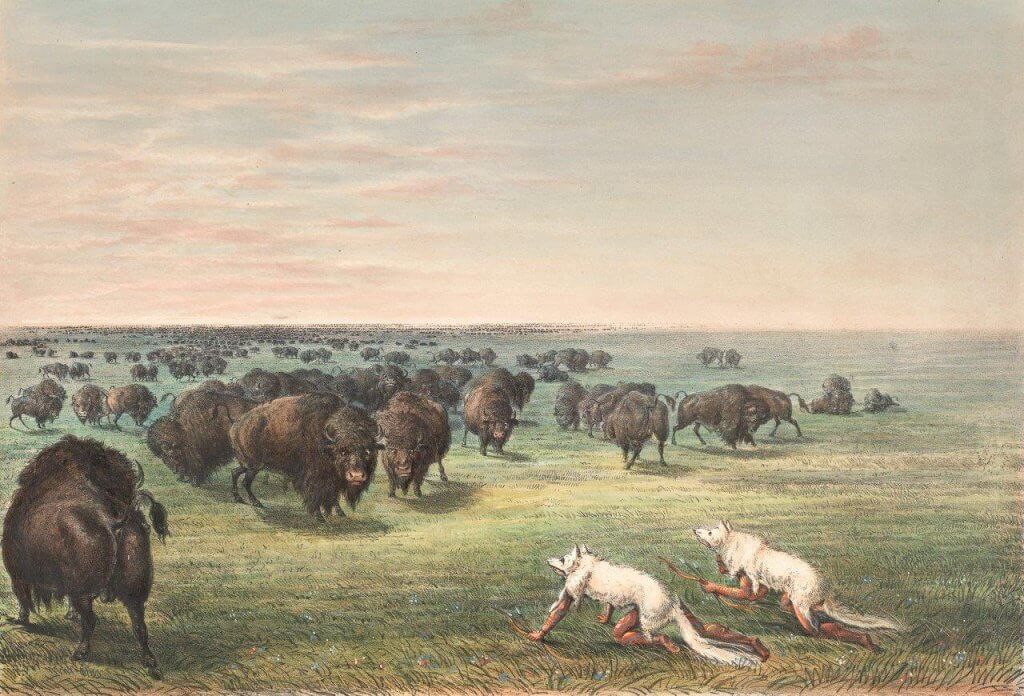

“The scent of our party was borne directly across the Platte, and we could distinctly note every step of its progress through a distance of 8 or 10 miles, by the consternation and terror it excited among the buffaloes. The moment the tainted gale infected their atmosphere, they ran with as much violence as if pursued by a party of mounted hunters.”

Brink explains his version of the meaning conveyed by the moving drive lines of waving “fences” along the heights.

He wrote that the waving branches and grasses struck fear into the buffalo, because this kind of fence—waving along the high points was unknown to them. They feared what they did not know.

“Indians are stationed by the side of some of these stakes, to keep them in motion, so that the buffaloes suppose them ALL to be human beings,” notes Brink. This kept the buffalo down low as they moved on toward the trap.

Then Jack Brink imagined two more tricks of the wily hunters—the “array of ingenious ruses that allowed them to direct the path of bison movement.”

One was placing a trail of buffalo chips in the valley between the drive lines leading to the trap, so the buffalo thought they were following an existing trail.

“A herd of bison, frightened by hunters circling around them, could see and smell a safe path of escape in the form of a beaten trail marked with a line of chips,” says Brink.

He said he had never seen this recorded anywhere before. And obviously, any evidence would have been long gone over the centuries. But it makes perfect sense.

Grinnell wrote of using the manure patties in winter, “The line of buffalo chips. . . was conspicuous against white snow, and when the buffalo were running down the chute, they always followed it, never turning to the right nor to the left.”

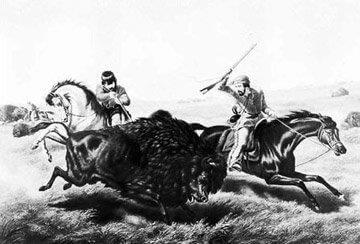

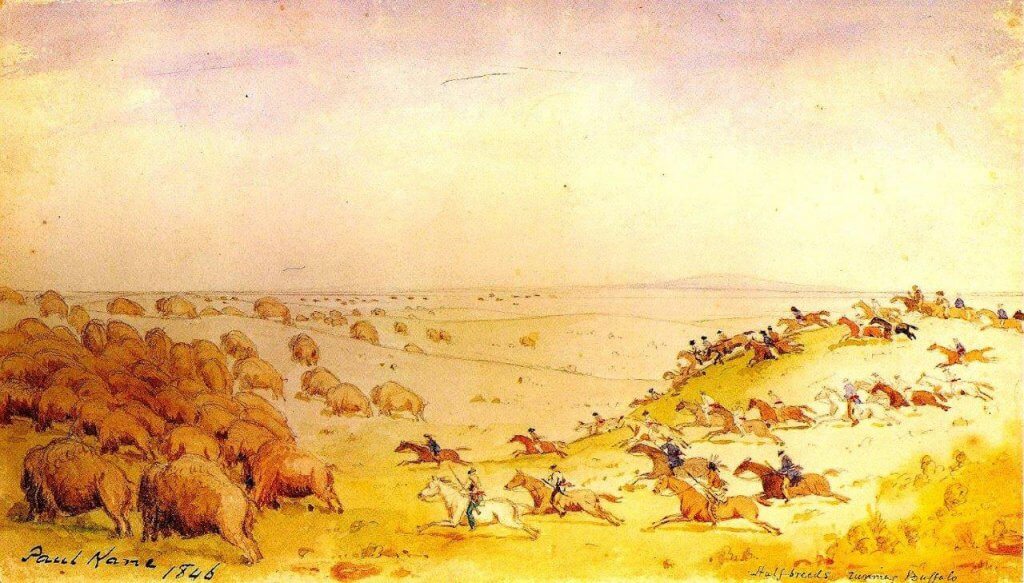

The second, maybe even stronger lure, came as a couple of ‘buffalo calves’ came into position between the herd and the drive lanes, moving just as young buffalo would, draped in calf skins and emitting perfect lost-calf bleats.

“Since the herd consists mainly of cows and calves—the preferred target group for nearly all Plains hunters—the trick has the desired effect,” wrote Brink.

“Cows raise their heads and check for their calves. Even if she knows her own calf is nearby, maternal instinct dictates that every cow will investigate the source of the plaintive bleating. A calf in danger cannot be ignored. The cows respond and start after the ‘lost calves.’

“The buffalo runners continue their hoax, wandering slowly away from the herd, into the mouth of the funnel, toward a mighty hunting party laying in wait . . . the herd continues to follow, walking into the jaws of the trap.”

Jack Brink talks about the stampede in his book as the buffalo entered the drive lanes. “It might sound as if a full-blown stampede of bison was in progress. Far from it.

“The great majority of movement leading up to and through the drive lanes was almost certainly of a much more gentle, though deliberate, nature. . . The drive probably consisted of short bursts of movement where the herd scampered ahead, followed by a lull where the hunters purposefully allowed them to rest and remain calm.

“Patiently, the hunters waited for the herd to regroup, perhaps resume grazing and then looked for an opportunity to nudge them ahead another short distance.”

Even today in corralling their buffalo, herd manager Robbie Magnon, of Fort Peck Sioux and Assiniboine Reservation in northeastern Montana, tells me the best way to avoid stressing the buffalo is by spending a couple of days bringing them in.

He says between their large pasture and the working corral are two or three successively smaller pastures. The first day, driving several pickup trucks, the Fort Peck crew might not bring the buffalo through the first gate, but by exerting gradual pressure from a distance, patiently haze them closer.

That night the herd might walk through the open gate on its own. The handlers drive through, close the gate and proceed in the same way toward the next one.

Near the end of the trap, writes Brink, “The tapering of the funnel permitted greater numbers of people to congregate along the narrowest parts of the lane, where the need for control, and the danger, was greatest.”

The Box Canyon or Arroyo Trap

Box Canyons and natural traps have claimed less attention than buffalo jumps—which left great heaps of bones and arrow points beneath the jumps. But Marcel Kornfeld, George C. Frision and Mary Lou Larson in their book Prehistoric Hunters-Gatherers of the High Plains and Rockies, say that likely more buffalo died in various kinds of traps than were ever killed in buffalo jumps.

A classic example of what archaeologists call a ‘box canyon’ or ‘arroyo trap’ is the Hawkin site just south of Sundance, Wyoming. Bones and artifacts show that as many as 80 animals were driven from the bottom up to the headcut where they were trapped and killed. Dating analysis shows the Hawkin site was used as early as 6,600 years ago.

The Agate Basin arroyo site has been researched in northeastern Wyoming, as well as to some extent in the surrounding area in Montana and the Dakotas. Others are along the Cheyenne River south of the Black Hills, where arroyo traps have been identified.

Wyoming archeologists twice excavated the Wardell Buffalo Trap northeast of Big Piney. Used 800 to 1,600 years ago, hunters drove their herds as far as a mile, with sagebrush and grease-wood wings extending about a half mile toward the river to help funnel buffalo into that trap.