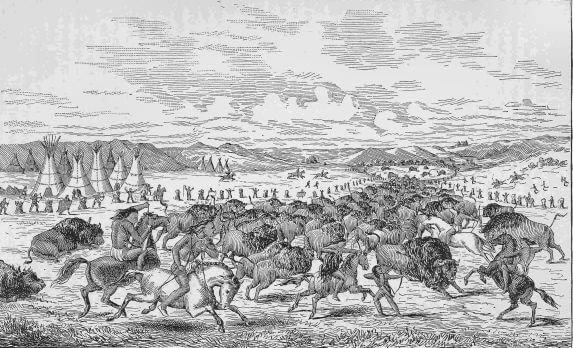

The surround may have been the earliest method for communal hunts before prehistoric people had horses or guns. The defensive buffalo gradually began to mill into a circle. As buffalo on the outside were killed, they piled up and trapped others within the circle until all were killed. Later on, with horses as in this painting, the herd was more easily kept together in a tight circle. “Buffalo Hunt, Surround” by George Catlin, courtesy Amon Carter Museum.

This may have required less preparation than later drives, but considerable good luck and certainly an understanding of buffalo behavior.

In the surround, a band of prehistoric people, both men and women, cautiously encircled a band of buffalo of manageable size.

“Then running in circles around the terrified animals, yelling loudly, they would slowly close the circle, making it smaller and smaller. . . At the appropriate time they would let go with their lances and arrows,” writes Dary.

If all went according to plan, the confused buffalo began to mill in a defensive circle, instead of running away. Typically, the bulls would tend to circle protectively around the outside, with cows and calves in the middle.

The hunters fired their lances, darts and arrows, killing the bulls in front of them.

As they fell, they piled up a barrier of bodies around the circle, trapping the live buffalo within the circle until all were killed.

George Bird Grinnell, author of The Cheyenne Indians, described a surround that used a decoy from early interviews he did with tribal elders.

“The people would go out on the prairie and conceal themselves in a great circle, open on one side. Then some man would approach the buffalo and decoy them into the circle.

“Men would now show themselves at different points and start the buffalo running in a circle, yelling and waving robes to keep them from approaching or trying to break through the ring of men.

“Of necessity this required great judgment and care, for once the herd started through in one direction it was impossible to turn. It would rush through the ring and be gone.”

Scouts are sent out ahead to find buffalo herds and consider how best to approach them. They follow time-honored protocol in going out and reporting back to the main hunting party. Credit CMRussell painting, Montana Historical Society.

“After swift-running men located a herd of buffalo, the chief told all the women to get their dog travois. Men and women went out together, approaching the herd from downwind so the animals wouldn’t get their scent and run off.

“The women were told to place their travois upright in the earth, small end up. The travois were so spaced that they could be tied together to form a semicircular fence. Women and dogs hid behind them.

“Two fast-running men circled the buffalo herd, approached the animals from upwind, and drove them toward the travois fence. Other men took positions along the sides of the route and closed in as the buffalo neared the travois.

“Barking dogs and shouting women kept the buffalo back. The men rushed in and killed the buffalo with arrows and lances.

“After the buffalo were killed the chief went into the center of the enclosure, counted the dead animals and divided the meat equally among the participating families.

“He also distributed hides to the families for making lodge covers. The women hauled the meat and hides to camp on their dog travois. This was called a surround of the buffalo.”

The Surround took advantage of the landscape when possible, such as driving the buffalo into natural traps, and bogs in blind canyons.

Logs, trees or large rocks may have been incorporated to form a barrier or fence on one side.

The risk was that sometimes the frantic buffalo would break through a weak spot—with all the others following close behind. Once they began to escape, hunters on foot could not stop or turn the fleet and agile buffalo.

Likely the earliest of these prehistoric hunters used the Spearthrower or atlatl—a tool that uses leverage to achieve greater velocity in dart of javelin-throwing. It’s a long-range weapon that can reach speeds of 93 mph. Stone age spear-throwers—could send a dart 100 meters or yards, but it was most accurate at 20 meters or less.

Impounding—Building Corrals

Impounding is viewed as more difficult than the surround, since it required building a buffalo-proof enclosure and finding a buffalo herd nearby.

However, once set up, it was likely more successful.

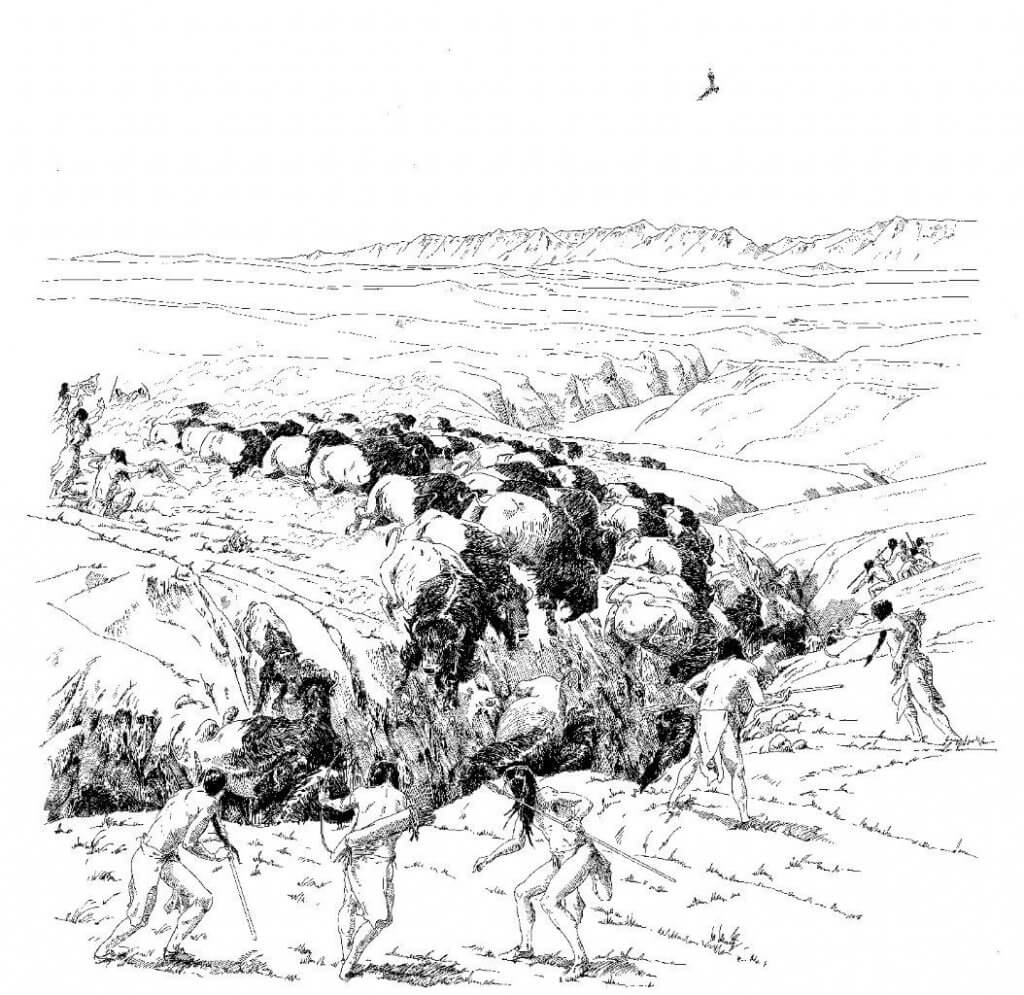

“Cree Indians impounding buffaloes.” An Impound often included drive lines leading down a hill into some kind of corral or enclosure. There the herd could be trapped and slaughtered. Prof HY Hind’s Red River, Assiniboine and Saskatchewan Expedit. Credit Wm Hornaday.

Old Weasel Tail described the impound method, thus:

“Near the edge of timber and toward the bottom of a downhill slope the Indians built a corral of wooden posts set upright in the ground to a height of about seven feet. They connected the posts by cross-poles tied in place with rawhide ropes.”

The downward slope was important—as were drive lines and wings bringing the Buffalo to the entrance.

“Around three sides of the corral they laid stakes over the lowest cross-poles. Their butt ends were firmly braced in the ground outside the corral. These stakes projected about three feet inside the corral at an angle, so their sharpened ends were about the height of a buffalo’s body.

“If the buffalo tried to break through the corral they would be impaled on these stakes.”

The hunters fired their weapons until all the buffalo in the corral were slaughtered, while women and children guarded any weak sections with waving robes and shouting.

The scene was bloody.

As one observer said, “The scene was more repulsive than pleasant or exciting. A great number were already killed and the live ones were tumbling about furiously over the dead bodies of their companions, and I hardly think the space would have held them all alive without some being on top of others, and in addition the bottom of the pound was strewn with fragments of carcasses left from former slaughters in the same place.”

And another: “People running frantically around the mound of animals trying to kill the wounded and yet avoid being killed. . . After firing their arrows they generally succeeded in extracting them again by a noose on the end of a pole, and some had even the pluck to jump into the area and pull them out with their hands—but if an old bull or a cow happened to observe them they had to be very active in getting out again.”

“Even mere boys and young girls”—were stationed on the walls of the corral—”all busy plying bows and arrows, guns and spears and even knives, to compass the destruction of the buffalo.

“Bison stumbling, rolling, dragging themselves from the pyramid.

“Animals of every age were huddled together in all the forced attitudes of violent death. Some lay on their backs with eyes starting from their heads and tongue thrust out through clotted gore. . . One little calf hung suspended on the horns of a bull which had impaled it in the wild race round and round the pound.”

Jack Brink in his book Imagining Head-Smashed-In recorded that every animal in the pound had to be killed, to enable the people to get to the meat. Also he said there was a spiritual belief that the buffalo now knew too much and if some escaped, would alert others and ensure the failure of future attempts.

Drive Lines Critical in Moving Buffalo

With the development of the Impounding method of trapping buffalo, drive lines comparable to the often-complex drive lines of Buffalo Jumps began to take shape.

Old Weasel Tail explained how Drive Lines worked above the impoundment corral.

“From the open side of the corral the fence of poles extended into two wings outward and up the hill. These lines were further extended by piles of cut willows in the shape of conical lodges about half the height of a man, tied together at their tops. . . spaced at intervals of several feet.

“On the hill just above the corral opening a number of poles were placed on the ground crosswise of the slope and parallel to each other. The buffalo had to cross these poles to enter the corral. The poles were covered with manure and water, which froze and became slippery so that once the buffalo were in the corral they couldn’t escape by climbing back up the hill.

“Before the drive began, a beaver bundle owner removed the sacred buffalo stones from his bundle and prayed.

“He sang a song, ‘Give me one buffalo or more. Help me to fall the buffalo.’”

The hunters had numerous special rites, adds Brink, “Ceremonies and taboos associated with buffalo and the hunting of this animal. It is absolutely correct to state that everything about a buffalo hunt, from beginning to end, was steeped in spiritual beliefs and appropriate ceremony.”

Buffalo have an excellent sense of smell and hearing. The wind brings both, and the ancient hunters clearly understood that.

Brink quotes one observer, who travelling through vast herds of buffalo one day in 1820, wrote:

“The scent of our party was borne directly across the Platte, and we could distinctly note every step of its progress through a distance of 8 or 10 miles, by the consternation and terror it excited among the buffaloes. The moment the tainted gale infected their atmosphere, they ran with as much violence as if pursued by a party of mounted hunters.”

Brink explains his version of the meaning conveyed by the moving drive lines of waving “fences” along the heights.

He wrote that the waving branches and grasses struck fear into the buffalo, because this kind of fence—waving along the high points was unknown to them. They feared what they did not know.

“Indians are stationed by the side of some of these stakes, to keep them in motion, so that the buffaloes suppose them ALL to be human beings,” notes Brink. This kept the buffalo down low as they moved on toward the trap.

Then Jack Brink imagined two more tricks of the wily hunters—the “array of ingenious ruses that allowed them to direct the path of bison movement.”

One was placing a trail of buffalo chips in the valley between the drive lines leading to the trap, so the buffalo thought they were following an existing trail.

“A herd of bison, frightened by hunters circling around them, could see and smell a safe path of escape in the form of a beaten trail marked with a line of chips,” says Brink.

He said he had never seen this recorded anywhere before. And obviously, any evidence would have been long gone over the centuries. But it makes perfect sense.

Grinnell wrote of using the manure patties in winter, “The line of buffalo chips. . . was conspicuous against white snow, and when the buffalo were running down the chute, they always followed it, never turning to the right nor to the left.”

The second, maybe even stronger lure, came as a couple of ‘buffalo calves’ came into position between the herd and the drive lanes, moving just as young buffalo would, draped in calf skins and emitting perfect lost-calf bleats.

“Since the herd consists mainly of cows and calves—the preferred target group for nearly all Plains hunters—the trick has the desired effect,” wrote Brink.

“Cows raise their heads and check for their calves. Even if she knows her own calf is nearby, maternal instinct dictates that every cow will investigate the source of the plaintive bleating. A calf in danger cannot be ignored. The cows respond and start after the ‘lost calves.’

“The buffalo runners continue their hoax, wandering slowly away from the herd, into the mouth of the funnel, toward a mighty hunting party laying in wait . . . the herd continues to follow, walking into the jaws of the trap.”

Jack Brink talks about the stampede in his book as the buffalo entered the drive lanes. “It might sound as if a full-blown stampede of bison was in progress. Far from it.

“The great majority of movement leading up to and through the drive lanes was almost certainly of a much more gentle, though deliberate, nature. . . The drive probably consisted of short bursts of movement where the herd scampered ahead, followed by a lull where the hunters purposefully allowed them to rest and remain calm.

“Patiently, the hunters waited for the herd to regroup, perhaps resume grazing and then looked for an opportunity to nudge them ahead another short distance.”

Even today in corralling their buffalo, herd manager Robbie Magnon, of Fort Peck Sioux and Assiniboine Reservation in northeastern Montana, tells me the best way to avoid stressing the buffalo is by spending a couple of days bringing them in.

He says between their large pasture and the working corral are two or three successively smaller pastures. The first day, driving several pickup trucks, the Fort Peck crew might not bring the buffalo through the first gate, but by exerting gradual pressure from a distance, patiently haze them closer.

That night the herd might walk through the open gate on its own. The handlers drive through, close the gate and proceed in the same way toward the next one.

Near the end of the trap, writes Brink, “The tapering of the funnel permitted greater numbers of people to congregate along the narrowest parts of the lane, where the need for control, and the danger, was greatest.”

The Box Canyon or Arroyo Trap

Box Canyons and natural traps have claimed less attention than buffalo jumps—which left great heaps of bones and arrow points beneath the jumps. But Marcel Kornfeld, George C. Frision and Mary Lou Larson in their book Prehistoric Hunters-Gatherers of the High Plains and Rockies, say that likely more buffalo died in various kinds of traps than were ever killed in buffalo jumps.

A classic example of what archaeologists call a ‘box canyon’ or ‘arroyo trap’ is the Hawkin site just south of Sundance, Wyoming. Bones and artifacts show that as many as 80 animals were driven from the bottom up to the headcut where they were trapped and killed. Dating analysis shows the Hawkin site was used as early as 6,600 years ago.

The Agate Basin arroyo site has been researched in northeastern Wyoming, as well as to some extent in the surrounding area in Montana and the Dakotas. Others are along the Cheyenne River south of the Black Hills, where arroyo traps have been identified.

Wyoming archeologists twice excavated the Wardell Buffalo Trap northeast of Big Piney. Used 800 to 1,600 years ago, hunters drove their herds as far as a mile, with sagebrush and grease-wood wings extending about a half mile toward the river to help funnel buffalo into that trap.

A turn in this washout above the South Grand to the left of where a Forest Service Ranger is standing—hides the steep headcut around the corner that could have acted as a trap or box canyon. Credit Francie M Berg.

At the fence corner they take the steep sandy trail down toward the water. About halfway down the trail, off to the right, is a dry gulch with steep sides and a headcut that could have acted as a trap or box canyon.

Like other Plains rivers, the South Grand repeatedly cuts into the buttes lining its banks, washing away the face of steep cliffs and breaking out new gulches and draws. Some gulches lead to an abrupt headcut where floodwaters have dropped in waterfalls—forming a steep wall at the upper end of the gulch.

Let’s imagine a family group of 5 to 8 prehistoric hunters looking down on a band of buffalo here in the low grassy area along the South Grand River among the cottonwood trees.

From the plateau above, the hunters would have planned their approach. Scanning the area for drive lines used in previous hunts would have perhaps revealed two or three possibilities. They’d want the breeze in their faces coming from the buffalo to avoid sending early warnings.

They decide to bring the buffalo into the gulch at an opening along the near side of the river on the narrow strip of land that runs below the bank.

For this they will need to drive the buffalo up along the north side of the river, past the point where it turns abruptly against the bank. The hunt leaders recognize the weak links in this plan and determine where to station persons to step out of hiding at just the right moment.

If all goes well, three or four hunters haze the entire herd from a careful distance along the trail under the bank.

As the buffalo reach an opening in the bank, imagine that a woman and dog step out ahead. Seeing her, they turn smoothly into the gulch, relieved to find an escape route. Twists and turns in the brushy gulch disguise what lies ahead—a deep box canyon with high straight sides.

The hunters rush forward to slaughter as many buffalo as possible, piling up large bodies across the narrow entrance. Up above wait women with children and dogs, ready to jump out of hiding when needed, to guard any weak points and keep the panicked animals down in the gulch.

Off to the left of the sandy trail is another long draw with sides too gradual for trapping buffalo. An ideal route for hikers to return to the flat above—it’s a nice draw for climbing, following one of the many deer trails going up both sides through shady cottonwoods.

Although this dry gulch trap has not been excavated, others in this general have been, several nearby in northeastern Wyoming.

In this sketch early hunters take advantage of a small, tight canyon with steep sides where buffalo could be prevented from climbing out by hunters stationed at the weak points. Jack Brink points out that buffalo running downhill are at a disadvantage because of the weight of their large heads and forequarters. Courtesy “Imagining Head-Smashed-In,” JBrink.

How buffalo were trapped in a dry gulch or box canyon is a method that archaeologists are paying closer attention to today, thanks to the diligence of Wyoming researchers.

The difficulty in researching arroyo traps and box canyons are the reason they’ve been neglected, the Wyoming experts tell us.

The evidence of traps tends to wash far downstream and scatter in many directions, in contrast to buffalo jumps—where big piles of bones, arrowheads and butchering tools are preserved at the site, usually protected by layers of earth.

With traps, the bones and artifacts lie in the bottom of draws and canyons washed by every flood. Heavy runoff through the centuries carries most of the remains farther on downstream.

However, some collect with mud and trash to form a barrier—even changing the course of streams. The solid barrier may be waiting for the next bone-hunting anthropologist to expose it at a later time with more runoff.

Note: Just a few miles downstream from Site 5, the Shadehill Buffalo Jump (Site 6) rises from the lake, dammed during the 1950’s. The same prehistoric hunters who might have hunted box canyons higher up the river likely used that jump for large communal hunts.

Trapped in Deep Snow or Sand

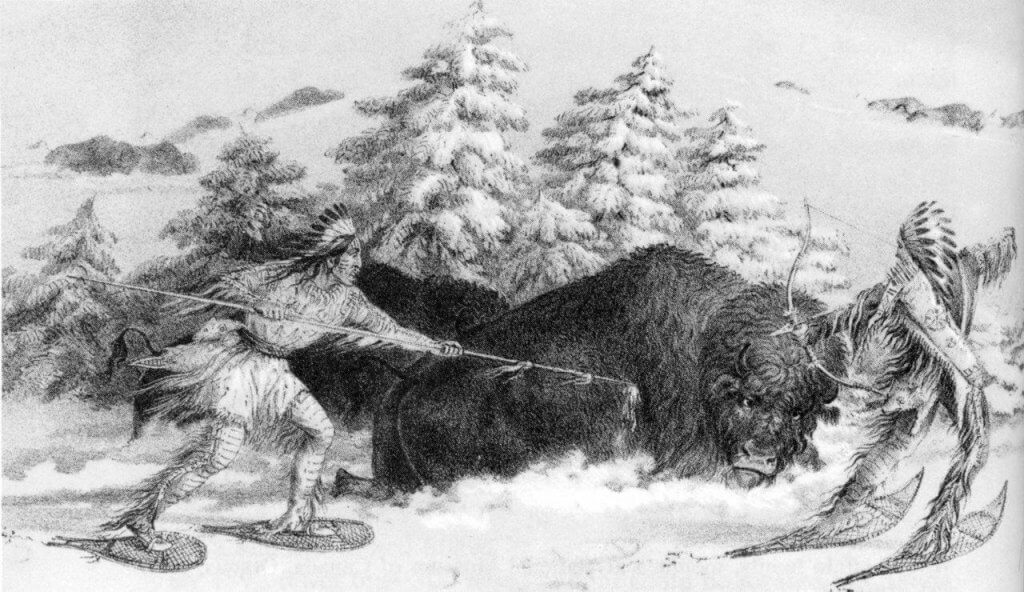

“Buffalo Hunt on Snow shoes,” George Catlin lithograph from his American Indian Portfolio. Credit Wm Hornaday.

In winters of deep snow Cheyenne hunters led trained dogs on the hunt, according to Grinnell. They chased the buffalo into the deepest drifts in draws, set free dogs to worry them and then ran up and killed them with lances.

Buffalo floundering in pockets of deep snow, fighting off dogs, were easy prey even for hunters on foot. After killing and cleaning buffalo, the ancient owners fed the dogs, then loaded packs on the dogs or harnessed them into dog travois to carry the meat back to camp.

After the packs were taken off, the dogs circled back to the kill to eat their fill. Females with young pups returned to camp to disgorge food for their young—and then raced back for more.

Another hunt in deep snow is described by Paul Kane, the Canadian artist:

“Upon ascending the bank, we found ourselves in the close vicinity of an enormous band of buffaloes, probably numbering nearly 10,000. The snow was so deep that the buffaloes were either unable or unwilling to run far and at last came to a dead stand.

“We therefore secured our horses and advanced towards them on foot to within 40 or 50 yards when we commenced firing, which we continued to do until we were tired of a sport so little exciting. For, strange to say, they never tried either to escape or to attack us.”

Some tribes fashioned snow shoes for deep-snow winters. Buffalo could also be trapped on ice in wintertime.

Similarly, at times a buffalo herd could be trapped in deep sand.

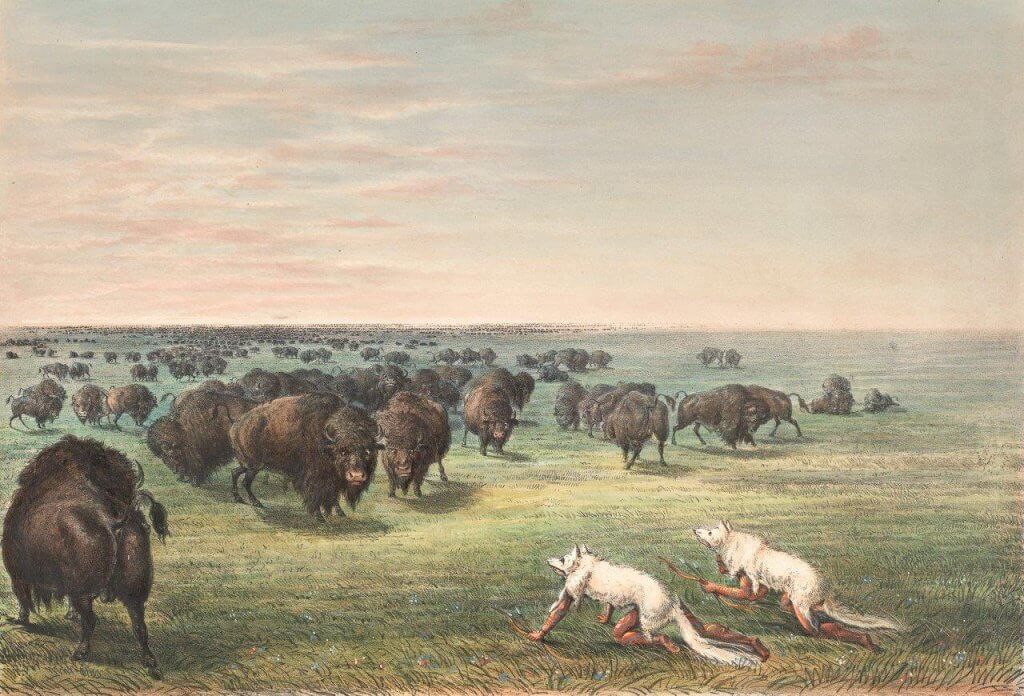

Disguises—Making a Calf or Snake

Sometimes hunters disguised themselves with animal skins to get close to their prey without startling them.

The skins of wolves were often used, as wolves commonly hung out with buffalo herds. They were not much of a risk to healthy buffalo in a herd, but often picked off any isolated weak or old animals.

This famous George Catlin painting provided two versions of Native hunters disguised in wolf skins. In this version the hunters carry weapons. Perhaps hunting alone, they may intend to kill a fat-looking buffalo that comes close. The second version, without weapons, may have been about enticing a curious herd to follow prancing ‘wolves’ into a trap during a communal hunt. Courtesy Amon Carter Museum, Ft Worth, Texas.

Another trick was performed by two men, one covering himself with a wolf pelt, the other with a buffalo robe, said Kane, hunting in Canada.

“We fell in with a small band of buffaloes and Francois initiated me into the mysteries of ‘making a calf,’” explained Kane.

“They crawl on all fours within sight of the buffaloes and as soon as they have engaged their attention, the pretend wolf jumps on the pretend calf, which bellows in imitation of a real one. The buffaloes seem to be easily deceived in this way.

“As the bellowing is generally perfect, the herd rush to the protection of their supposed young with such impetuosity that they do not perceive the cheat until they are quite close enough to be shot.

“Indeed, Francois’ bellowing was so perfect that we were nearly run down. As soon, however, as we jumped up, they turned and fled.

“We shortly afterwards fell in with a solitary bull and cow and again ‘made a calf.’

“The cow attempted to spring toward us, but the bull seeming to understand the trick, tried to stop her by running between us. The cow dodged and got round him and ran within ten or fifteen yards of us, with the bull close at her heels, when we both fired and brought her down.

“The bull instantly stopped short and, bending over her, tried to raise her up with his nose, evincing the most persevering affection for her. Nor could we get rid of him so as to cut up the cow without shooting him also, although bull flesh is not desirable at this season of the year.”

In using disguises, Native people took on not just the appearance of the animal they had become, but they moved as it did.

“Having thousands of years to observe the behavior of all the game of the Plains, these fellow residents of the land would have an intimate knowledge of how each species walks, runs, sways, pauses, sniffs the air, lowers its head and paws the earth . . . They transformed themselves,” wrote Jack Brink.

Another ruse of the two Canadians was ‘Making a snake.’

“Which we often practiced with great success at Edmonton. It consisted in crawling on our bellies and dragging ourselves along by our hands, being first fully certain that we were to the leeward of the herd, however light the wind, lest they should scent us.

“Should there be twenty hunters engaged in the sport, each man follows exactly in the track of his leader, keeping his head close to the heels of his predecessor.

“The buffaloes seem not to take the slightest notice of the moving line, which the Indians account for by saying that the buffalo supposes it to be a big snake winding through the snow or grass.”

Other Ways of Slaughter

When food was scarce good hunters went out often, alone or with a few friends.

In oral histories gathered by A.B. Welch is a story told of an outstanding hunter named John Grass from the Mandan, Arikara and Hidatsa tribes in northern Dakota.

One extremely cold day Grass took a small hunting party out from camp on foot.

“John Grass was carrying his bow. He carried his arrow carrier in front that time. His left hand froze tight about the bow. They could not open his fingers.”

Then they found a buffalo, which they killed.

“They cut it open along the belly and shoved his arm and bow inside. His hand was melted then. That was a very bad thing that time.”

Single hunters could pick off old bulls separated from the herd and wounded by wolves, provided they could hold off the pack of wolves.

It was said that Flathead hunters were skilled at killing buffalo by rock throwing, choking or knifing them.

A South Dakota report tells of Native hunters digging hiding places or caves in soft banks near trails leading down to water. Then they hid in the cave and killed buffalo as they came to drink.

Then came the horse. Soon after, trade guns. And the exciting horse culture of running buffalo on the Plains prevailed for 150 years!

References:

Brink, Jack W. “Imagining Head-Smashed-In: Aboriginal Buffalo Hunting on the Northern Plains,” 2008. Athabasca University Press, Edmonton, Canada.

Dary, David A. “The Buffalo Book: Full Saga,” Chicago: Swallow Press, 1974. Davis, Leslie B. and John W. Fisher Jr., Editors. “Pisskan: Interpreting First Peoples Bison Kills at Heritage Parks,” 2016. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Densmore, Frances. “Teton Sioux Music: Song to Secure Buffalo in time of Famine.” https://www.questia.com;read/77737640/teton-sioux-music.

Ewers, John C. “The Blackfeet: Raiders on the Northwestern Plains.” Norman: U of Oklahoma Press, 1958., p11-13. ACLib)

Garcia, Louis. Personal Communication and “The History and Culture of the Spirit Lake Dakota,” Tokio, ND.

Gilfillan, Archer. SD Highway Magazine, 1939. South Dakota Game, Fish and Parks. Grinnell, George Bird. “The Cheyenne Indians,” Vol 1 and Vol 2, 1928, Bison Books.

Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump, Personal visit, June 15-23, 2016. Hornaday, William T. “The Extermination of the American Bison,” Report of the National Museum, 1887. Reprinted in book form by Gov. Printing Office, 1889.

Johnsgard, Paul A. “Prairie Dog Empire: Saga of the Shortgrass Prairie.” Lincoln: U of Nebraska Press, 2005.

Kornfeld, Marcel, George C. Frison and Mary Lou Larson. “Prehistoric Hunters-Gatherers of the High Plains and Rockies,” 3rd Edition, 2010. Left Coast Press, Walnut Creek, CA.

Lame Deer, John (Fire) and Richard Erdoes. “Lame Deer Seeker of Visions.” NY: Simon and Schuster, 1972.

Magnon, Robert. Fort Peck Sioux and Assiniboine Reservation, Visit and Personal Communication.

Merriman, Don. ShadeHill, Personal Communication, 2015.

Ulm Pishkun State Park, Personal visit, June 15-23, 2016.

Vore Buffalo Jump, Personal Visit and Interviews 2016, Vore Buffalo Jump

Waggoner, Josephine. “Witness: A Hunkpapha Historian’s Strong-Heart Song of the Lakotas.” Edit Emily Levine. U of Nebr Press, Lincoln, 2013.

Welch, A.B. Colonel. Source: Online www.Welchdakotapapers.com. “Oral history of the Dakota Tribes 1800s-1945: As Told to Colonel A.B. Welch.”

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog