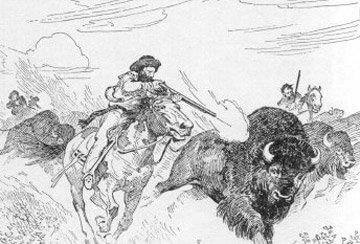

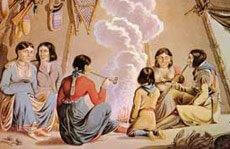

Paul Kane painted many scenes of Métis men hunting buffalo, including this one. The red sash worn by the man on the ground in front was typical of the capote worn by Métis.

Paul Kane was an artist and writer who followed the Buffalo hunting Métis onto the western Canadian plains and observed, painted and wrote about them. Born in 1810—while he was still a boy his family emigrated from Ireland to the Toronto area.

Always interested in art, he spent 4 years in Europe studying painting, mostly copying the style of old masters. In England he may have met George Catlin and seen some of his 1830s paintings of Native tribes on the Great Plains of the US. This inspired him to bring together a visual record of the Native people of Canada.

In June 1846 Kane left his home in Toronto to hunt buffalo with the Red River Métis—pronounced Mah tee’ or Mah tees’—from Ft. Garry (now Winnipeg).

Kane soon found that to get safely into the interior of Canada where he could paint many different tribes, he needed a sponsorship from the Hudson Bay Company.

He was fortunate in being able to meet with Sir George Simpson of Hudson Bay, who gave him the papers he needed. Simpson granted Kane free board, lodging and transportation to trading posts in Hudson Bay territory (which was roughly one quarter of North America)—in exchange for a dozen sketches of Native American life for Simpson’s personal museum of “Indian curiosities.”

Kane set off across Canada all the way to the Pacific Ocean—going from one trading post to the next. Sometimes he travelled by water with a fleet of voyagers—sometimes he rode horseback, alone with an interpreter or guide.

He missed by only a few days a Métis group that had just left on a buffalo hunt. Without delay he purchased a cart for his tent, a saddle-horse for himself, hired a Métis helper to drive and hurried to catch up.

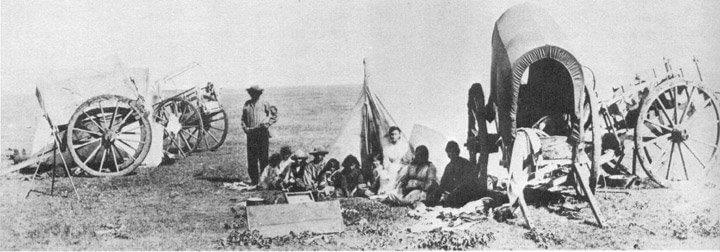

Three days later they joined one of the bands of “200 hunters, besides women and children” who welcomed him “with the greatest cordiality.”

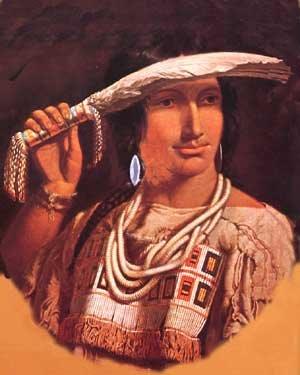

Self Portrait by Paul Kane, artist, painted about 1845.

The Métis at Ft. Garry, he wrote: “are more numerous than whites and now amount to 6,000. These are the descendants of the white men in the Hudson’s Bay company’s employment and the Native Indian women. They all speak the Cree language and the Lower Canadian Patois.

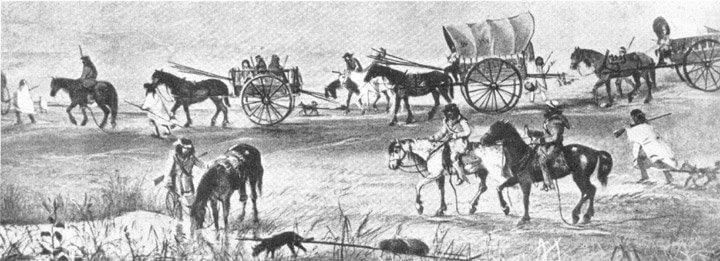

“Here the tribe is divided into three bands, each taking a separate route for the purpose of falling in with the herds of buffaloes. These bands are each accompanied by about 500 carts, drawn by either an ox or a horse,” he writes.

“Their cart is a curious-looking vehicle, made by themselves with their own axes and fastened together with wooden pins and leather strings—nails not procurable. The tire of the wheel is made of buffalo hide and put on wet. When it becomes dry it shrinks and is so tight that it never falls off and lasts as long as the cart holds together.

“The carts containing the women and children—each decorated with some flag or other conspicuous emblem on a pole, so that the hunters might recognize their own from a distance–wound off in one continuous line, extending for miles, accompanied by the hunters on horseback.

Traveling to buffalo ranges, the carts with Métis women and children extended for miles, accompanied by hunters on horseback. In recording their travels, Paul Kane’s method was to sketch as many scenes and portraits as he could on the spot in pencil, oils or charcoal, and then later spend more time in painting similar scenes.

Attack by Sioux Hunters

“A very hardy race of men, [they are] capable of enduring the greatest hardships and fatigues—but they make poor farmers, neglecting their land for the more exciting pleasures of the chase.

“Their camps while on the move, are always preceded by scouts, for the purpose of reconnoitering either for enemies or buffaloes. If they see the latter they give a signal by throwing up handfuls of dust. And if the former, by running their horses to and fro.

Métis and the caravan, taking a break for lunch, while scouts went on ahead to scan the horizon for enemies or buffalo. The Sioux deeply resented the Métis’ wholesale slaughter of large herds on what they considered their own hunting grounds.

Three days later the scouts in the distance were seen riding back and forth—the signal of enemies being in sight.

Kane writes, “Immediately 100 of the best mounted hastened to the spot and, concealing themselves behind the shelter of the bank of a small stream, sent out two as decoys—who exposed themselves to the view of the Sioux.

“The latter, supposing them to be alone, rushed upon them, whereupon the concealed [Métis] sprang up and poured in a volley amongst them, which brought down eight. The others escaped, although several must have been wounded—as much blood was afterwards discovered on their track.

“The following afternoon we arrived at the margin of a small lake, where we camped earlier than usual for the water. Next day I was gratified with the sight of a band of about 40 buffalo cows in the distance and our hunters in full chase. They were the first I had seen but were too far off for me to join in the sport.

Buffalo Hunting

“They succeeded in killing 25, which were distributed through the camp and proved most welcome to all of us, as our provisions were getting rather short—and I was abundantly tired of pemmican and dried meat.

The hunters, “Succeeded in killing 25, which were distributed through the camp and proved most welcome to all of us, as our provisions were getting rather short—and I was abundantly tired of pemmican and dried meat,” wrote Kane.

“The fires being lighted with wood we had brought with us in the carts, the whole party commenced feasting with a voracity which appeared perfectly astonishing to me, until I tried myself and found by experience how much hunting on the plains stimulates the appetite.

“For the next two or three days we fell in with only a single buffalo, or small herds of them, but as we proceeded they became more frequent.

“At last our scouts brought in word of an immense herd of buffalo bulls about two miles in advance of us. They are known in the distance from the cows by their feeding singly and being scattered wider over the plain—whereas the cows keep together for the protection of the calves, which are always kept in the center of the herd.

According to Kane, a Métis named Hallett “who was exceedingly attentive to me, woke me in the morning to accompany him in advance of the party, that I might have the opportunity of examining the buffalo whilst feeding before the commencement of the hunt.

“Six hours’ hard riding brought us within a quarter mile of the herd. The main body stretched over the plains as far as the eye could reach. Fortunately the wind blew in our faces. Had it blown towards the buffaloes they would have scented us miles off.

“I wished to have attacked them at once but my companion would not allow me until the rest of the party came up—as it was contrary to tribal law. We therefore sheltered ourselves from the observation of the herd behind a mound, relieving our horses of their saddles to cool them.

“In about an hour the hunters came up, about 130 and immediate preparations were made for the chase. Every man loaded his gun, looked to his priming and examined the efficiency of his saddle-girths.

“The elder men strongly cautioned the less experienced not to shoot each other. A caution by no means unnecessary—as such accidents frequently occur.

“Each hunter then filled his mouth with balls, which he drops into the gun without wadding. By this means loading much quicker and being enabled to do so whilst his horse is at full speed. It is true that the gun is more liable to burst, but that they do not seem to mind.

“The scene now became one of intense excitement. The huge bulls thundering over the Plain in headlong confusion, whilst the fearless hunters rode recklessly in their midst, keeping up an incessant fire at but a few yards’ distance from their victims.

“Upon the fall of each buffalo, the successful hunter merely threw some article of his apparel—often carried by him solely for that purpose—to denote his own prey—and then rushed on to another. These marks are scarcely ever disputed, but should a doubt arise as to the ownership, the carcass is equally divided among the claimants.

“The chase continued only about one hour, and extended over an area of from 5 to 6 square miles, where might be seen the dead and dying buffalos to the number of 500.

“In the meantime my horse which had started at a good run, was suddenly confronted by a large bull that made his appearance from behind a knoll within a few yards of him. Being thus taken by surprise, he sprung to one side and getting his foot into one of the innumerable badger holes, with which the plains abound, he fell at once. I was thrown over his head with such violence that I was completely stunned.

“Some of the men caught my horse and I was speedily remounted. I again joined in the pursuit and coming up with a large bull, I had the satisfaction of bringing him down at the first fire.

“Excited by my success I threw down my cap and galloping on soon put a bullet through another enormous animal. He did not however fall, but stopped and faced me pawing the earth, bellowing and glaring savagely at me. The blood was streaming profusely from his mouth and I thought he would soon drop.

“The position in which he stood was so fine that I could not resist making a sketch. I accordingly dismounted and had just commenced when he suddenly made a dash at me. I had hardly time to spring on my horse and get away from him, leaving my gun and everything behind.

“When he came up to where I had been standing, he turned over the articles I had dropped, pawing fiercely as he tossed them about and then retreated towards the herd. I immediately recovered my gun and having reloaded, again pursued him and soon planted another shot in him. This time he remained on his legs long enough for me to make a sketch.

“I have often witnessed an Indian buffalo hunt since, but never one on so large a scale.”

As he returned to camp, he came upon “One of the hunters coolly driving a wounded buffalo before him. In answer to my inquiry why he did not shoot him, he said he would not do so until he got him close to the lodges as it would save the trouble of bringing a cart for the meat. He had already driven him seven miles and afterwards killed him within 200 yards of the tents.

“That evening while the hunters were still absent a buffalo, bewildered by the hunt, got amongst the tents and at last got into one—after having terrified all the women and children, who precipitately took flight.

“When the men returned they found him there still. And being unable to dislodge him, they shot him down from the opening in the top.”

Buffalo Hunting methods

The hunting methods used by the Métis were far different from that of their Indian ancestors. Instead of driving bison off cliffs or into pounds and corrals on foot, they had horses and guns from the first, provided by their fathers and grandfathers. Their Native mothers taught them buffalo culture.

They ran their trained buffalo horses into the herd, picked out a fat cow and fired point-blank at full gallop. Experienced hunters on buffalo horses could kill 10 to 12 buffalo in a two-hour run.

The Métis hunters had horses and guns from the first, provided by their fathers and grandfathers. They trained their horses to move in close to the targeted buffalo—they could kill 10 to 12 buffalo during a two-hour run.

“The sagacity of the animal is chiefly shewn in bringing his rider alongside the retreating buffalo, and in avoiding the numerous pitfalls abounding on the prairie. The most treacherous of the latter are the badger holes.

“Considering the bold nature of the sport, remarkably few accidents occur. The hunters enter the herd with their mouths full of bullets. A handful of gunpowder is let fall from their powder horns—a bullet is dropped from the mouth into the muzzle, a tap with the butt end of the firelock on the saddle causes the salivated bullet to adhere to the powder during the second necessary to depress the barrel, when the discharge is instantly effected without bringing the gun to the shoulder.”

Kane recorded the Métis’s buffalo adventures not only in paintings and sketches, but also in colorful narratives, collected later in his book “Wanderings of an Artist Among the Indians of North America” published in London in 1859.

As Canada’s first artist of national significance he has an interesting and important place in the history of Canadian art and ethnography. However, he does not escape criticism and questions about his authenticity—it was said his final paintings did not always match with the sketches he had made on site.

During his 2 voyages through the Canadian northwest in 1845 and from 1846 to 1848 Kane sketched and painted Métis people who lived around the forts as well as Indians from a variety of tribes who came to visit or trade at the forts. Everywhere along the way he made sketches, in pencil, watercolor or oil.

He made two voyages through the Canadian northwest—in 1845 and from 1846 to 1848.

During those years Kane sketched and painted Métis people who lived around the forts as well as Native people from other tribes who came to visit or trade at the forts. Everywhere along the way he made sketches, in pencil, watercolor or oil.

Hudson Bay after 1821 had a monopoly and operated about 100 isolated outposts along the major fur trade routes.

What he found in the Métis, Kane wrote was, “A race, who, keeping themselves distinct from both Indians and whites, form a tribe of themselves. Although they have adopted some of the customs and manners of the French voyageurs.”

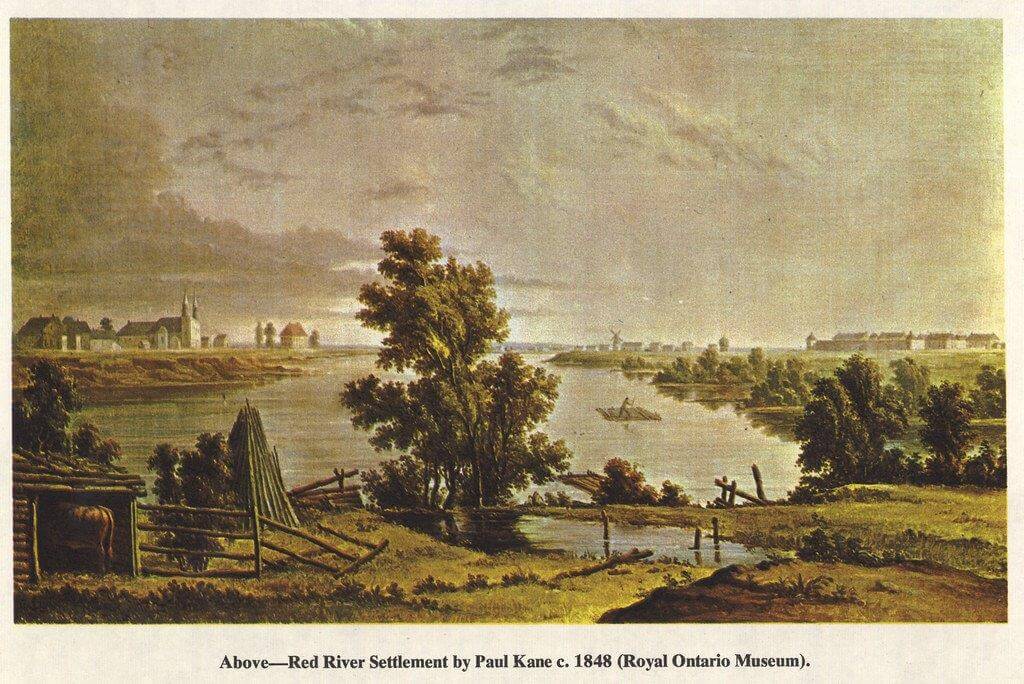

Metis settlements on the Red River were located upstream as far as Pembina, ND, and downstream to Lake Winnipeg and Hudson Bay.

Métis hunts involved organizing hundreds of men, women, children, Red River carts and horses for the westward journeys which covered vast stretches of the Plains to harvest the buffalo where they grazed. On the return trip, tons of processed buffalo meat and hides were shipped for the fur and hide trade.

Buffalo hunts provided the Métis with an impressive organizational structure. By 1820 it was a permanent feature of life for all individuals on or near the Red River and other Métis communities.

The Red River Métis became famous for their buffalo hunts. However, experts say this was largely because of the abundance of writers and observers who passed through that area along the Red River between Winnipeg and Pembina publicizing their large hunts and pemmican trade.

Actually the Red River Métis were on the eastern edge of the pemmican commerce and only came late to the game.

Métis buffalo hunting and the making of pemmican for trade actually began in the late 1700s farther north and west. Fur trading companies looked for food items that could last their traders on long trips. The buffalo hunters showed them that pemmican was an ideal product, since it could be stored for long periods of time without spoiling.

During the early 1800s, Canadian Métis established themselves as suppliers of pemmican to the new world.

The first Métis communities appeared in Ontario, particularly around the Great Lakes, and Eastern Canada. As the fur trade moved west, so did the French-Canadian fur traders. Métis settlements were located as far west as British Columbia, and as far north as the Mackenzie River in the Northwest Territories.

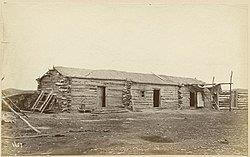

Some who participated in the northern hunts preferred to stay out on the Prairie in winter camps. Roughly 30 such settlements have been found in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Montana. Their small villages consisted of about 40 or 50 rough-hewn, flat sod-roofed cabins.

Métis lived in log cabins near or within fur trading forts. They were first and foremost buffalo hunters.

Among their many other names, the Métis were also known as Buffalo Hunters. Although they sustained themselves in a variety of ways—such as fishing, trapping for furs, practicing small-scale agriculture and working as wage laborers for the Hudson Bay Company—they were first and foremost buffalo hunters.

There were usually two organized hunts each year: one in the spring and one in the fall. The buffalo hunts of this time were carried out through almost militaristic precision.

Often a priest accompanied the devout Métis hunters and one of their rules was ‘No Hunting, No travel’ on Sundays.

Kane reported that the first organizational meeting for the hunt was held and a President selected. A number of captains were nominated by the President and the people jointly. The captains then proceeded to appoint their own policemen, the number assigned to each not exceeding ten.

Their duty was to see that the Laws of the hunt were strictly carried out. Guides were responsible for the camp flag that remained raised until it was time to settle for the night. At the end of the day the captains took charge.

Arrival at Fort Edmonton

A favorite fur trading fort for Paul Kane was the Edmonton trading post on the Plains of central Alberta. There he arrived in deep snow amid temperatures of 40 and 50 below. He rode across the Continental Divide the end of November and spent the rest of the winter there.

Kane observed the men working in the ice pits. He wrote “The buffaloes range in thousands close to the fort. The men had already commenced gathering their supply of fresh meat for the summer in the ice pit.

“This is made by digging a square hole capable of containing 700 or 800 buffalo carcasses. As soon as the ice in the river is of sufficient thickness, it is cut into square blocks of a uniform size with saws. With these blocks the floor of the pit is regularly paved and the blocks cemented together by pouring water in between them and allowing it to freeze solid.

“In like manner the walls are solidly built up to the surface of the ground.

“The head and feet of the buffalo when killed are cut off, and the carcass without being skinned is divided into quarters and piled in layers in the pit as brought in, until it is filled up, when the whole is covered with a thick coating of straw, which is again protected from the sun and rain by a shed.

“In this manner the meat keeps perfectly good through the whole summer, and eats much better than fresh killed meat, being more tender and better flavored.”

Five or six gentlemen prepared for a buffalo hunt to which Kane was invited.

First they selected their horses. “We had our choice of splendid horses, as about a dozen are kept in the stables for the gentlemen’s use from the wild band of 700 or 800. Which roam about the fort and forage for themselves through the winter, by scraping snow away from long grass with their hoofs.

“They have only one man to take care of them, he follows them about and camps near them with his family. This would appear a most arduous task. But instinct soon teaches them that their only safety from their great enemies, the wolves, is by remaining near the habitations of man.

“These horses are kept and bred for the purpose of sending off pemmican and stores to other forts during the summer. In winter they are almost useless, on account of the depth of snow.

After going about 6 miles on a wagon trail the hunters saw a band of buffalo on the bank.

“A dog who had sneaked after us—running after them, gave the alarm too soon—and they started off at full speed. We caught the dog and tied his legs together and left him lying in the road to await our return.

“About 3 miles further we came to a place where the snow was trodden down in every direction and on ascending the bank, we found ourselves in the close vicinity of an enormous band of buffaloes, probably nearly 10,000.

“The snow was so deep they were either unable or unwilling to run far, and at last came to a dead stand. We therefore secured our horses and advanced towards them on foot to within 40 or 50 yards. We commenced firing, which we continued to do until we were tired of a sport so little exciting.

“For strange to say, they never tried either to escape or attack us.

“Seeing a very large bull, I thought I would kill him for the purpose of getting the skin of his enormous head and preserving it. He fell. But as he was surrounded by three others that I could not frighten away, I was obliged to shoot them all before I could venture near him—although they were all bulls and are not generally saved for meat.

“The sport proving rather tedious, from the unusual quietness of the buffaloes, we determined to return home and send the men for the carcasses and remounted our horses.

“But before we came to the river we found an old bull standing right in our way. Mr. Harriett, the chief, for the purpose of driving him off, fired at him and slightly wounded him. Then he turned and made a furious charge. Mr. Harriett barely escaped by jumping his horse on one side. So close, indeed was the charge, that the horse was slightly struck on the rump.

”The animal still pursued Mr. Harriet at full speed and we all set after him, firing ball after ball into him, as we ranged up close to him without any apparent effect than that of making him more furious and turning his rage on ourselves.

“This enabled Mr. Harriett to reload and plant a couple more balls in him. We were now all close to him and we all fired deliberately at him. At last after receiving 16 bullets in his body, he slowly fell.

“On our return, we told the men to bring in the cows we had killed, numbering 27, with the head of the bull I wanted. Whereupon the women—who have always this job to do, started off to catch the requisite number of dogs.

“These dogs are quite as valuable as horses, as it is with them that everything is drawn over the snow,” Kane observed. The snow at Edmonton was so deep in winter that horses could not be used. “Yet no care is taken of [the dogs] except that of beating them sufficiently before using them, to make them quiet for the time they are in harness. Painting by Paul Kane.

“About the fort there are always 200 or 300 who forage for themselves like the horses and lie outside. These dogs are quite as valuable as horses, as it is with them that everything is drawn over the snow. Two of them will easily draw in a large cow. Yet no care is taken of them except that of beating them sufficiently before using them, to make them quiet for the time they are in harness.

“It would be almost impossible to catch them were it not for the stratagem of tying light logs to them, which they drag about. By this means they soon catch as many as they want and bring them into the fort where they are fed—sometimes—before being harnessed.

“Early next morning I was roused by a yelling and screaming that made me rush from my room, thinking we were all being murdered. And there I saw the women harnessing dogs.

“Such a scene! The women were like so many furies with big sticks, threshing away at the poor animals, who rolled and yelled in agony and terror until each team was yoked up and started off.

“During the day the men returned, bringing the quartered cows ready to be put in the ice-pit. And my big head, which before skinning I had put in the scales and found that it weighed exactly 202 lbs. The skin of the head I brought home with me.

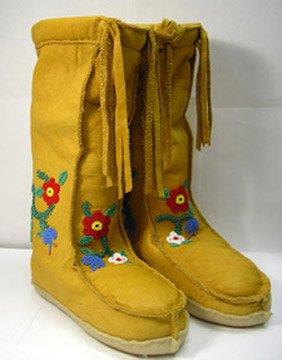

The Métis women often decorated with beadwork borrowed from French floral designs. These Muckluks were worn in winter time.

“The fort at this time of the year presented a most pleasing picture of cheerful activity. Everyone was busy; the men, some in hunting and bringing in the meat, some in sawing boards in the saw-pit and building boats.

“The women find ample employment in making moccasins and clothes for the men, putting up pemmican in 90-pound bags, and doing all the household drudgery, in which the men never assist them.

“Evenings are spent round their large fires in eternal gossiping and smoking. The sole musician a fiddler is now in great requisition amongst the French part of the inmates, who give full vent to their national vivacity, whilst the more sedate Indian looks on with solemn enjoyment.

‘No liquor is allowed to the men or Indians. But want of it did not in the least seem to impair their cheerfulness.

Christmas at Ft Edmonton

On Christmas day the flag was hoisted and by 2 o’clock they sat down to a delicious dinner in the spacious dining hall, which was about 50’ by 25’.

Boiled buffalo hump, a boiled unborn buffalo calf, white fish browned in buffalo marrow, buffalo tongue—all considered delicacies—were served along with beavers’ tails and roast wild goose. Also piles of potatoes, turnips and bread.

“Long will it remain in my memory, although no pies, puddings or blanc manges shed their fragrance over the scene.

That evening they held a dance for all the inmates of the fort. The dancers were “glittering in every ornament they could lay hands on. Whether civilized or savage, all were laughing and jabbering in as many different languages as there were styles of dress.

Kane says that about 130 people–traders, their Native wives and children—the Métis —lived within the walls of the Edmonton trading post in comfortable log houses, supplied with abundant firewood.

“English was little used—as none could speak it but those who sat at the dinner table.

“Occasionally I led out a young Cree [woman] who sported enough beads round her neck to have made a peddler’s fortune.

“Having led her into the center of the room, I danced round her with all the agility I was capable of exhibiting to some highland-reel tune which the fiddler played with great vigor. Whilst my partner with grave face kept jumping up and down, both feet off the ground at once.

A half-Cree girl—her poetic name was Cunne-wa-bun—or ‘One that looks at the Stars.’ Posing for a picture, she held her swan’s wing fan with an ornamental handle of porcupine quills “in a most coquettish manner,” according to Kane, who later painted her in two styles.

“Another lady with whom I sported the light fantastic. . . whose poetic name was Cunne-wa-bun—or ‘One that looks at the Stars’ was a half-Cree girl. I was so much struck by her beauty that I prevailed upon her to promise to sit for her likeness, which she afterwards did with great patience—holding her fan made of the tip end of swan’s wing with an ornamental handle of porcupine’s quills in a most coquettish manner.”

Making a Calf

A few days later Kane went out hunting with Francois Lucie, a Métis voyageur and his friend.

“We fell in with a small band of buffaloes and Francois initiated me into the mysteries of ‘making a calf.’

“This ruse is performed by 2 men, one covering himself with wolf skin, the other with buffalo skin. They then crawl on all fours within sight of the buffaloes and as soon as they have engaged their attention, the pretend wolf jumps on the pretend calf, which bellows in imitation of a real one.

‘As the bellowing is generally perfect, the herd rush on to the protection of their supposed young with such impetuosity that they do not perceive the cheat until they are quite close enough to be shot.

“Indeed, Francois’ bellowing was so perfect that we were nearly run down. As soon as we jumped up they turned and fled [leaving 2 dead cows behind].

“We shortly afterwards fell in with a solitary bull and cow and again ‘made a calf.’ The cow attempted to spring towards us, but the bull seeming to understand the trick, tried to stop her by running between us.

“The cow however dodged and got round him and ran within 10 or 15 yards of us—with the bull close at her heels, when we both fired and brought her down.

“The bull instantly stopped short and bending over her, tried to raise her up with his nose—evincing the most persevering affection for her. Nor could we get rid of him so as to cut up the cow, without shooting him also—although bull flesh is not desirable at this season of the year, when the female can be procured.

“Having loaded our horses with the choice parts of the 3 cows we had killed, we proceeded home.”

Another day, another trick—taught Kane by Francois was “making a snake.” For this the 2 men crawled on their bellies, dragging themselves along by their hands.

“Being first fully certain that we were to the leeward of the herd, however light the wind, lest they should scent us—until we came within a few yards of them, which they would almost invariably permit us to do.

“Should there be 20 hunters engaged, each follows exactly in the track of his leader, keeping his head close to the heels of his predecessor.

“The buffaloes seem not to take the slightest notice of the moving line, which the Indians account for by saying that the buffalo supposes it to be a big snake winding through the snow or grass.”

Exhausted as he was after the days’ hunt, Kane stayed up late that night watching a dazzling performance of the northern lights.

“It extended from the east to the west across the zenith. In its center, immediately overhead appeared a blood-red ball of fire—of greater diameter than the full moon rising in a misty horizon. From the ball emanated rays of crimson light, merging into a brilliant yellow at the northern edges.

“The belt also on the northern side presented the same dazzling brightness, while the snow and every object surrounding us was tinted by the same hues.

“I continued lost in admiration of this splendid phenomenon until past one in the morning, when it still shown undiminished if not increased brilliance.

“The Indians have a poetical regard for the Aurora Borealis, which is in this high latitude remarkably brilliant, shooting up coruscations of surprising splendor. These they think are the spirits of the dead dancing before the Manitou or Great Spirit.”

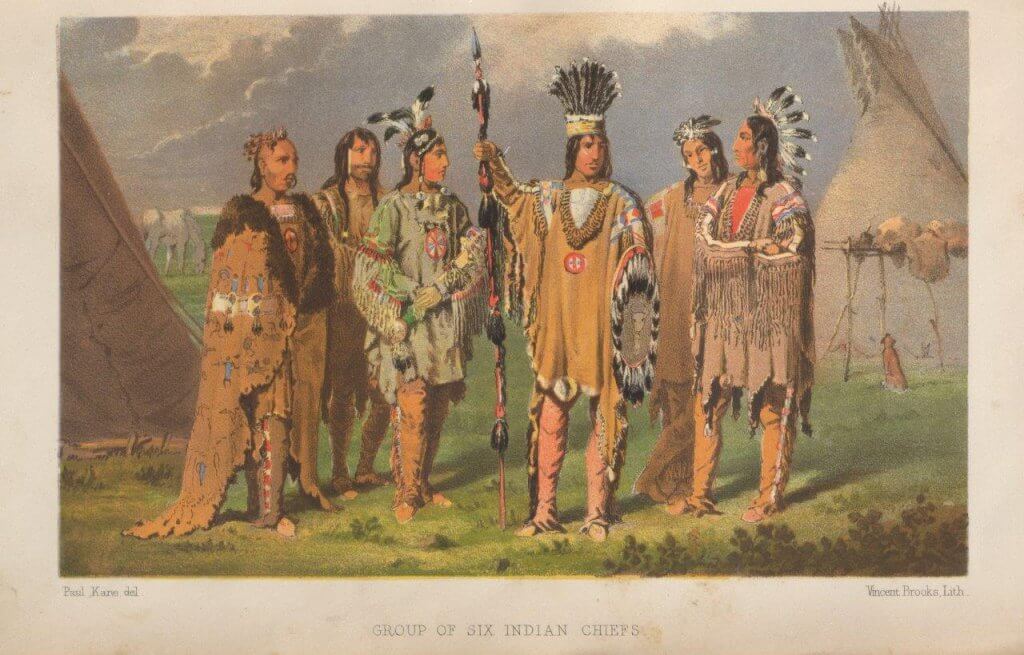

A group of war chiefs from a large party of 1500 warriors headed for Fort Edmonton in pursuit of Crees and Assiniboines. Paul Kane, who painted them, said they included Big Snake in the center, Miskemekin “The Iron Collar” a Blood Indian chief with his face painted red, and Little Horn on the left with a buffalo robe draped round him. “As they were expecting to have a fight with the Crees next day, they got up a medicine dance in the afternoon and I was solemnly invited to attend, that I might add my magical powers,” he wrote.

Travelling home that fall Kane joined a brigade of voyagers, making portages with Mr. Harriet in the lead boat—“being lighter and generally better built than the rest.”

Homeward Bound

Their fleet arrived at Grand Rapids. “And the whole brigade shot down them—a distance of three and a half miles,” writes Kane.

“No rapid in the whole course of navigation on the eastern side of the mountains is at all to be compared to this in velocity, grandeur or danger. The brigade flies down as if impelled by a hurricane, many shipping a good deal of water in the perpendicular leaps which they often had to take in the descent.

“The whole course is one white sheet of foam from one end to the other!”

They arrived in Sault Ste Marie by Oct 1 and he finished the trip by steamboat.

Paul Kane brought home to Toronto some 500 sketches, from which he completed 100 paintings and published the book Wanderings—a detailed record of his travels throughout Canada. He has been criticized for romanticizing the Native people in a European way, giving viewers what they expected, rather than what he saw.

Kane married Harriet Clench in 1853. She was an accomplished artist and a drawing and painting instructor. They had four children, two sons and two daughters.

Kane’s home in Toronto, built upon his marriage to Harriet Clench in 1853. Now a historic site. They had four children, two sons and two daughters. Paul Kane died Feb. 20, 1871.

The oil paintings he completed in his studio are considered an essential part of Canadian heritage in recording those early times, although it was said he embellished some of them considerably, departing from the accuracy of his field sketches in favor of more dramatic scenes.

In 1857, Kane fulfilled his commissions of more than 120 oil canvases for his patron George W Allan, the Parliament and Simpson of Hudson Bay. His works were shown at the World’s Fair at Paris in 1855, where they were reviewed very positively.

In 1879 the hunters on the prairies of Canada reported that only a few buffalo were left of the great herds and within two years the last of the buffalo herds in Montana Territory were also gone.

Source: Wandering of an Artist Among the Indians of North America: From Canada to Vancouver’s Island and Oregon, Through the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Territory and Back Again, by Paul Kane, published in London by Longman, Brown, Green and Roberts in 1859. Respectfully dedicated to George William Allan, ESQ. as a token of gratitude for the kind and generous interest he has always taken in the Author’s labors, as well as a sincere expression of admiration of the liberality which, as a native Canadian, he is ever ready to foster Canadian talent and enterprise. Toronto: July 9, 1858.)

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog