Long in the works, the 250 to 300 buffalo that live on this refuge as well as the National Bison Range itself have been turned over to the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes as of Dec. 27, 2021, when President Donald Trump signed it into law. These tribes have strong historical, geographic and cultural ties to the land and the bison. Credit Ryan Hagerty, US FWS.

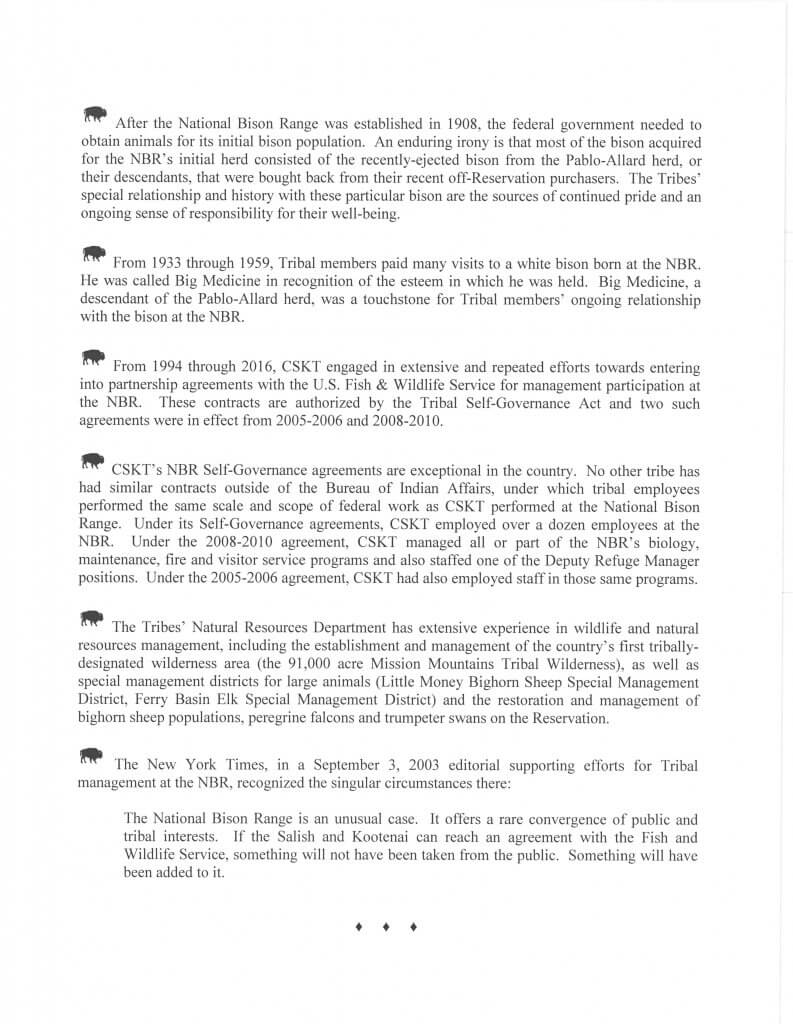

Established in 1908, the National Bison Range is being restored to the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Native American Tribes (CSKT) of Montana’s Flathead Indian Reservation.

The National Bison Range Restoration Act was signed into law by President Donald Trump on Dec 27, 2020, one of his last official acts.

According to the Char-Koosta News, after 113 years the Flathead tribal flag now flies at the National Bison Range.

The Yamncut Drum sings an Honor Song at the raising of the Flathead flag.

“It’s a very emotional day for the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, and officially reestablishing our footprints on the Bison Range. It’s been a long time coming,” said Flathead Tribal Council Chairwoman Shelly Fyant.

One lovely summer day my sister Anne and I visited the Bison Range near Moiese Montana, in the heart of the Flathead Indian Reservation. That was a year ago—before the transition from Federal Wildlife Service to the tribes.

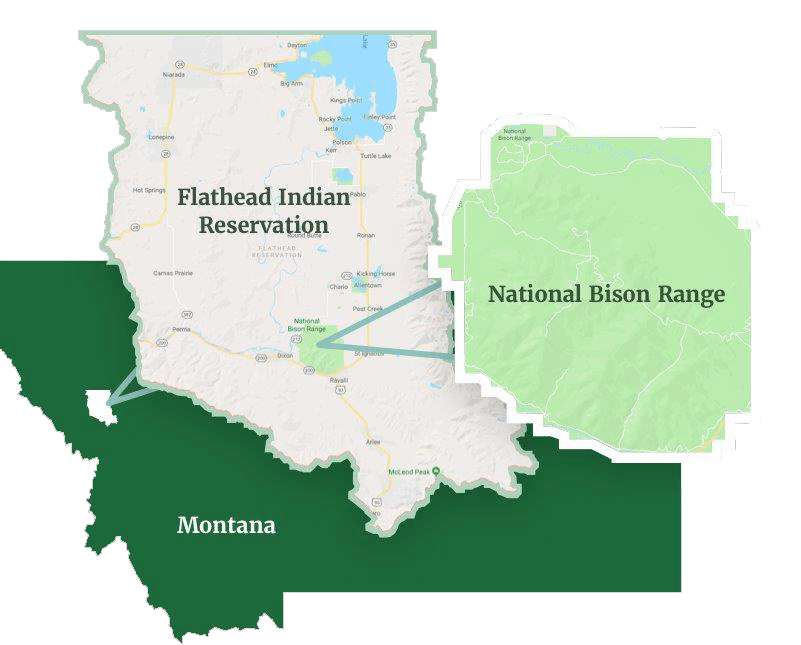

We found a nature trail as well as three wildlife drives on the range:

- West Loop and Prairie Drive are short year-round drives

- Red Sleep Mountain Drive (19 miles) takes you through the heart of the reserve and is open mid-May to Mid-October

We took the shorter loops where buffalo herds grazed leisurely across the roads in front and behind us.

Cows with their calves taking a break. Credit Bill West, US Fish and Wildlife.

Then we struck out on the 19-mile, one-way route up and over Red Sleep Mountain. Once committed, there’s no turning back.

And who would want to?

Well, yes, it can be a little scary—looking way down where you just came from. Looking up and ahead where you’ve yet to go.

Switchbacks take us up Red Sleep Mountain all the way to the top and then down on the other side.

Bison Range Heals

This beautiful and amazing 18,500-acre wildlife conservation area is now managed by the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes and open to the public.

“The ceremonial raising of the flag is symbolic of the mending of a broken circle that was caused by the federal government ripping asunder the land that belonged to the Flathead Nation in 1908 to establish the National Bison Range on that 18,800 acres in the heart of the Flathead Indian Reservation,” wrote Bernie Asure, editor of Charkoosta News in the May 13, 2021 issue.

“Welcome to the Homeland of the Séliš, Ql̓ispé and Ksanka people where the footprints of our Ancestors are. Where their hopes and dreams still carry on through us. The buffalo are a big part of our lives, of our traditions, of our culture,” says Séliš-Ql̓ispé Culture Committee Director Tony Incashola.

“As you know the buffalo almost disappeared from the face of the earth. When the buffalo disappeared, our people hurt.

“You can look at today as a beginning—a new beginning. A new start, for not only the Bison Range, but I would like to see this as the start of understanding of why it’s so important to Native Americans.”

“The buffalo are a big part of our lives, of our traditions, of our culture. As you know the buffalo almost disappeared from the face of the earth. I would like to see this as the start of understanding of why it’s so important to Native Americans,” says Incashola. Natl Park Service.

Why is understanding this so important, especially to the Séliš, Ql̓ispé and Ksanka people?

“It’s not just having it or controlling [the buffalo],” says Incashola. “it’s more of an opportunity to care. We must take care of them now as they took care of us.”

The restoration of the land that was taken against the will of the CSKT and the restored stewardship of the bison “brings a lot of healing for our people,” Fyant said. “We have a really hard working, dedicated staff that put a lot into this effort and we’re just so thankful for today.”

Fyant also thanked the present US FWS staff for their assistance during the transition period.

The 113 years of “long time coming” seemed to have been whiffed away with the same chilly breezes that snapped the flags of the US and the Flathead Tribes— for the first time ever at the soon to be former National Bison Range.

On one hand it’s still the National Bison Range as the US Fish and Wildlife Service is still in charge but on the other hand, as the Flathead flag indicates, things are changing there as a “long time coming” has arrived.

CSKT spokesman Robert McDonald said the public would see little change on the 18,800-acre wildlife refuge covering Red Sleep Mountain south of Pablo.

The Tribal Council agreed to continue following the conservation plan developed by FWS that controls how the refuge is managed for wildlife and the public.

“The Fish and Wildlife Service is still in place,” McDonald said on Friday. “The Tribal Council is in regular contact with them, and we’re working on an agreement for how things will progress and operate in the future.

“There are a lot of questions about staffing, positions, what should be added or remain—things like maintenance crews, biologists, people in the gift shop and cultural interpretation. We’re in the early process of hashing out how it’s going to go.”

McDonald said the mission of the refuge to be a publicly accessible landscape focused on preserving wild bison would not change.

On Thursday, CSKT officials announced they were replacing federal regulations governing hunting, fishing and recreation on the refuge with an essentially identical set of rules authorized by the Tribes.

Elk hang out near the water where they have always lived.

The replaced regulations include rules governing user fees to enter the refuge, prohibition of fireworks, weapons or explosives except under authorized circumstances, prohibition of hunting or taking of resources from the refuge except as authorized, and use of motorized vehicles.

McDonald said the exceptions would apply to actions previously allowed by FWS. Boy Scout troops, for instance, have been allowed to gather shed elk antlers and biologists have conducted studies involving capturing or occasionally killing specimen wildlife. Those exceptions would continue under tribal management, he said.

The original herd of bison released in 1909 was purchased with private money raised by the American Bison Society and then donated to the Refuge.

Today, 250 to 300 bison live on this refuge. To keep track of herd health, the Refuge conducts an annual Bison capture. And to ensure the herd is in balance with their habitat, surplus bison are donated and/or sold live, according to US Fish and Wildlife.

The CSKT are working with the US FWS in the transition phase of turning over the management reins of the NBR to the CSKT with an expected official turnover by the end of the year. The restoration of the NBR property to the Flathead Nation was part of its Federal Reserved Water Rights Compact.

The Tribes now refer to the NBR as the Bison Range, and there are discussions on renaming the NBR to a more CSKT-related name.

Scenery on Red Sleep Mountain

It’s the perfect place for a day trip complete with a rich history, breathtaking Mission Mountain views and magnificent wildlife photography opportunities.

The herds were below, near water, but here and there Anne and I saw those old lone buffalo bulls standing off by themselves on the mountain—meditating, grumbling, mulling over mistreatment by the reigning monarch, making their slow, meandering way up a draw, where they might glimpse the herd in the distance.

Spring brings red-gold buffalo calves, bird song and the first wildflowers on the buffalo range.

Summer’s the time for an early morning or evening visit when the mountain temperatures dip a bit cooler—perfect for new fawns and elk calf sightings.

Bighorn sheep rams are out and about more. And in fall bears are scavenging for wild berries amid golden autumn backdrops and bugling and sparring elk.

Winter is the time for bald-eagle and great-horned owl sightings.

President Theodore Roosevelt established the National Bison Range in 1908 to provide a permanent range for the herd of bison.

Today the range is a diverse ecosystem of grasslands, Douglas fir and ponderosa pine forests, riparian areas and ponds.

Big Horn Sheep, mountain lions, elk, deer, pronghorn antelope, bears and more than 200 species of birds call the Bison Range home.

Most memorable it is home to some 250 to 300 bison, as well as elk, deer, pronghorn antelope, bighorn sheep, mountain lions, bears and more than 200 species of birds.

You’ll find a nature trail or two as well as the three wildlife drives in the range: the two short drives you can take the year around. And Red Sleep Mountain Drive right through the heart of the reserve, up and over the top; it’s open mid-May to Mid-October.

As you gain altitude you see the rise of spectacular views of the towering Mission Mountains thrusting up their rugged peaks just beyond these foothill mountains.

For the next 19 miles, we followed the byway as it slowly snakes its way through draws, scattered forests, open hills as well as making its way along the top of a ridge.

The views from the byway are spectacular. At the beginning, visitors have unrestricted views of the Flathead River and the western part of the Mission Valley, along with the forested Salish Mountains.

As the drive meanders its way to the east and continues to gain elevation, the views open up, providing superb vistas of the snowy peaks of the Mission Mountains, the agricultural fields of the Mission Valley that lie 2,000 feet below, as well as more distant views of Flathead Lake and the Whitefish Range.

Lake views and soaring mountains are viewed during the drive down Red Sleep Mountain. Credit FWS.

Once the gravel road reaches the flats, the road changes character as it passes through open fields. The road also follows the Jocko River for a short distance. This section of the drive is excellent for viewing wildlife besides bison, as the Jocko River and the surrounding fertile grazing lands are home to deer, antelope and more.

Range elevation varies from 2,585 feet at headquarters to 4,885 feet at High Point on Red Sleep Mountain, the highest point on the Range.

Much of the National Bison Range was once under prehistoric Glacial Lake Missoula, which was formed by a glacial ice dam on the Clark Fork River about 13,000 to 18,000 years ago. The lake attained a maximum elevation of 4,200 feet, so the upper part of the Refuge was above water.

Old beach lines can be seen on north-facing slopes. Topsoil on the Range is generally shallow and mostly underlain with rock which is exposed in many areas, forming ledges and talus slopes.

Anyone visiting Northwest Montana (and if you’re visiting Glacier National Park, then you’re visiting NW Montana), should absolutely find the time to take this scenic and very unique byway.

Sudden Transition

Back in December, a bipartisan bill that would transfer the lands and management of the National Bison Range to the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes looked as if it might die in Congress with the end of the session.

But it didn’t. Instead, it got attached to a must-pass package of COVID-19 relief and government spending bills, and unexpectedly it passed.

After a century of work, it felt sudden, said Morigeau, a tribal member and attorney for the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes and a Montana state legislator. “It happened so fast, it just really hasn’t sunk in.”

Finally, after 113 years, the 18,800 acres of grassland, woodland, and wildlife that comprise the National Bison Range, along with its resident bison herd, were returned to the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes.

Today, the transfer has general support from the community, conservation groups and politicians. But the long journey included three rounds of failed agreements between the U.S. and the tribe, numerous lawsuits, a federal investigation and a massive public education campaign to quash rumors and stereotypes.

It comes at a time of a broader conversation on the return of land stewardship to tribal nations.

Also a Native woman—Deb Haaland of the Laguna Pueblos—pledges to oversee public-lands management as Interior Secretary for the first time in history.

Near the summit of Red Sleet Mountain two old bulls take a break from their ramblings.

When Shane Morigeau was growing up on the Flathead Indian Reservation, he knew that the land inside the fenced National Bison Range was different from the tribal lands elsewhere on the reservation, at the base of Montana’s Mission Mountains or the shores of Flathead Lake.

He remembers being a kid in his dad’s truck, driving past while his father explained that the lands inside the fence weren’t tribal lands anymore.

Why did the Flathead tribes feel shut out of the Bison Range on their own reservation?

As tribal elders tell, it was common knowledge that the fence was as much to keep them out as it was to keep bison in. “It happened long ago,” Morigeau said, but “it still resonates across generations.”

“It’s a reconciliation,” said Chairwoman Shelly Fyant. “We are such a place-based people. To have this land back, to be in control of it, is a fresh, new hope.”

History of the Buffalo Herd

The National Bison Range began as a small herd of free-roaming bison on the Flathead Indian Reservation managed by tribal members in the 1870s, while the bison around them were hunted to near-extinction.

Bison herds in the Mission Valley date back to the late 1800’s when a Pend d’Oreille man of the Flathead Reservation returned home from the plains of eastern Montana with four bison calves. The herd quickly grew to 13 animals.

The free-roaming bison were managed by tribal members while the bison around them were hunted to near-extinction.

At that point, partners Michel Pablo and Charles Allard bought the herd.

The Pablo-Allard herd thrived in the Mission Valley’s open grasslands. It became one of the largest private bison herds at the time when bison were most threatened with extinction.

However, when it was announced the Flathead Indian Reservation would be opened for homesteading in 1910, surviving partner Pablo began making arrangements to rid himself of his herd.

The US Government declined to purchase the bison so Pablo sold them all to Canada.

Just after this, the American Bison Society pushed the US government to set aside land to protect and conserve the American bison.

The National Bison Range was one such area. The American public pitched in to provide funds to purchase bison to place on the new Refuge.

The American Bison Society, under the direction of William Hornaday, solicited donations throughout the country. Over $10,000 was raised, enough to purchase 34 bison from the Conrad herd. Located in Kalispell, Montana, these bison were descended from the famous Pablo/Allard herd.

To supplement this, Alicia Conrad added two of her finest animals to the effort. The Refuge also received one bison from Charles Goodnight of Texas and three from the Corbin herd in New Hampshire. These 40 animals, all donated to the Refuge and coming from private herds, form the nucleus of 250 to 300 bison roaming the Range today.

During the allotment era in 1904 when tribal lands the U.S. declared surplus were sold, the federal government divvied up the reservation. It gave some 404,047 acres to settlers, 60,843 to the state of Montana, and 1,757 acres to the U.S. “for other purposes.”

Settlers flocked in, took up the lands, and today tribal members are a minority on their own reservation.

The U.S. retained tribal lands for the range, which was carved out of prime habitat in the middle of the reservation.

The National Bison Range is deep in the heart of the Flathead Reservation. The buffalo started as a small herd of free-roaming bison on the Flathead Indian Reservation managed by tribal members in the 1870s, while the bison around them were hunted to near-extinction. During the allotment era in 1904, when tribal lands the US deemed surplus were sold, the federal government divvied up the reservation, giving some 404,047 acres to settlers, 60,843 to the state of Montana, and 1,757 acres to the US “for other purposes.” Settlers flooded in, and today tribal members are a minority on their own reservation.

In 1908, President Theodore Roosevelt put the range under federal management. Tribal members did not work there.

The Salish word for this special piece of land means ‘the fenced-in place.’ The physical barrier grew into a powerful metaphor about how tribal members could relate to the lands taken from them, Fyant said.

But now, the tribes aim to put their energy into bringing their philosophy onto the range, telling the public about their priorities and sharing tribal stories.

Speaking of the return of the lands and Haaland’s potential as Interior secretary, Fyant summed it up simply: “It’s about . . . time.”

Many kinds of wildlife have co-existed on the Bison Range with the buffalo for generations. The tribes aim to put their energy into bringing their philosophy onto the range, telling the public about their priorities and sharing tribal stories.

Fish and Wildlife Co-Managed

Tribal efforts to co-manage the National Bison Range with the US Fish and Wildlife began in the early 1990s, but they were met with obstacles, despite the tribe’s established conservation record. (In 1982, for example, they became the first tribe to designate a wilderness area when it created the 92,000-acre Mission Mountain Tribal Wilderness.)

The tribes and the wildlife agency agreed to co-manage the range in 2004, but the arrangement crumbled after a small number of vocal federal employees and locals allied with an anti-Indigenous group, alleging mistreatment. It was a theme that continued for nearly two decades.

“The restoration of this land is a great historic event and we worked hard to reach this point. This comes after a century of being separated from the buffalo and the Bison Range, and after a quarter-century-long effort to co-manage the refuge with the Federal Wildlife Service,” says Fyant.

A new crop of calves greets the summer flowers. It’s a healing time for the Flathead tribes. “This comes after a century of being separated from the buffalo and the Bison Range, and after a quarter-century-long effort to co-manage the refuge with the Federal Wildlife Service,” says Fyant.

Caution: Buffalo can be dangerous.

“Nice park to enjoy the natural beauty and the sights of bison,” says local guide Steve Zamek.

“Rather than traveling counterclockwise the entire loop [that takes 2 hours] we took a left into the two-side traffic road and back. This takes about 40 min driving slowly. In my mind that’s a better way to explore the park as most bison stay close to the river. We saw elk, bison and deer. Great experience.”

Zamek recalls he was 8 years old the first time he visited the Bison Range. “Big Medicine, the only White Buffalo was there. I still have a large photo of him. Such magnificent animals.

“So glad the Range has been returned to the Flathead. They have been faithful stewards of the land and her animals forever. Innovation and guardians of Earth at great benefit to us and future generations of not only Tribal members, but everyone else as well,” says Zamek.

The Séliš, Qlispé, and Ksanka people warmly welcome you to the Bison Range, and we hope you

enjoy your visit!

Visitor Center and office: open from 7am to 8 pm.

Hours of Operation Front Gate Hours: 6am-8pm

Visitor Center Hours: 7am-8pm

Red Sleep Drive Hours: 6am-6pm; The Red Sleep Mountain Road takes visitors through the heart of the reserve. Trailers are prohibited on the road due to steep inclines, numerous sharp curves, and the road’s narrow width. This is a one-way road.

Contact Information Bison Range: (406) 644-2211

CSKT Natural Resources Department: (406) 883-2888 Visitor Information

In the spirit of Atatice

NEXT: Part 2: Metis Buffalo Hunters in Western Canada

________________________________

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog