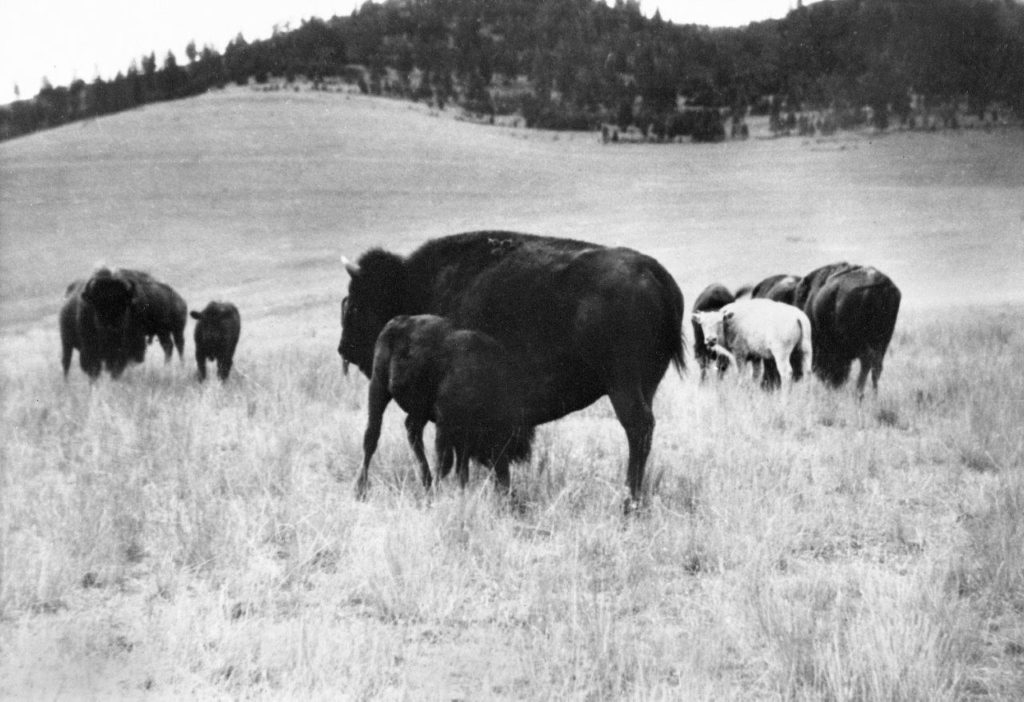

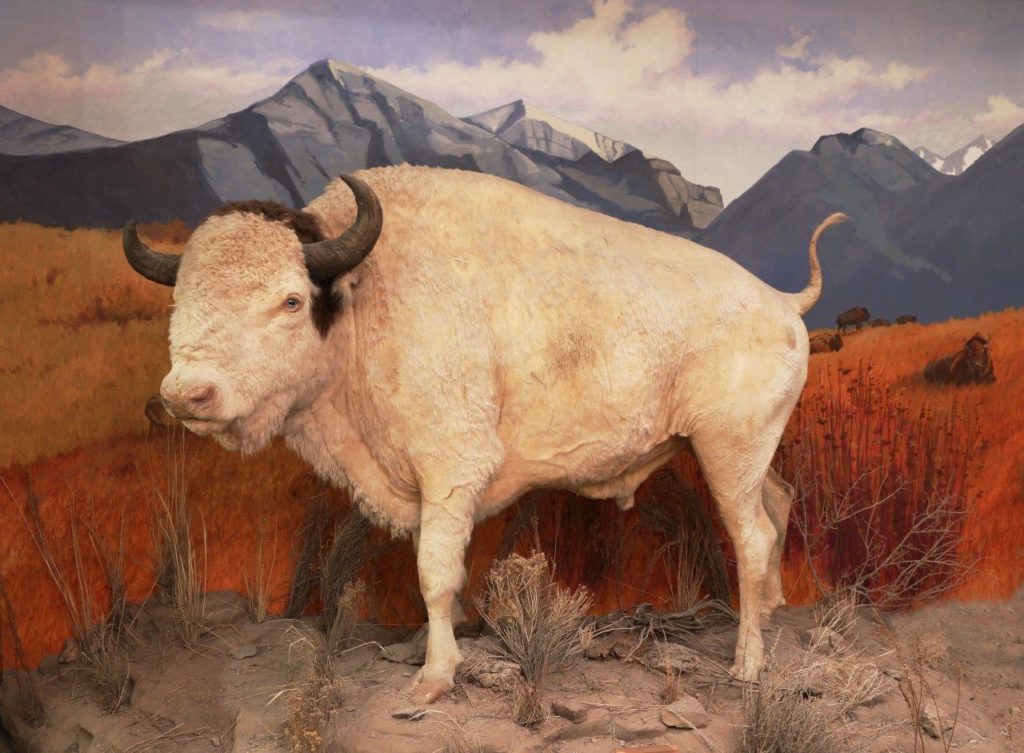

Big Medicine, born in 1933 on the National Bison Range in Western Montana, near the Flathead Indian Reservation, lived there all of his 26 years. He had a brown topknot between his horns, his eyes were blue and his horns and hooves were light colored. National Bison Range photo.

The most famous white buffalo that ever lived was probably Big Medicine, born in 1933 on the National Bison Range in Western Montana.

Soon after birth he was dubbed “Big Medicine” by the local Salish, Pend d’Oreille and Kootenai people of the Flathead Valley. He lived there all of his 26 years.

White buffalo are sacred to many Native American tribes and they believed he brought good news and supernatural powers. The Blackfeet tribe farther east also considered him the property of the sun as well as “good medicine.”

“The National Bison Range,” said Paul G. Redington, then chief of the Bureau of Biological Survey, “is maintained to assist in perpetuating the American buffalo. We are therefore much interested in having in the herd an example of a variation so rare as the white buffalo. When only one was known in a herd of more than five million, it is particularly interesting that we should have this big medicine in a herd of about 500 animals.”

Big Medicine posed for Tourist Photos

The buffalo expert, California biology professor Dale Lott, author of American Bison: A Natural History, was born in Montana on the National Bison Range in 1933, the same year as Big Medicine.

He grew up among the buffalo on the bison range, where his grandfather was the Range Superintendent and veterinarian.

In his book he mentions that, growing up, he often had his photo taken by visitors with his grandfather and the white buffalo who was nicknamed “Old Whitey” by park employees.

His father lived and worked there and married the boss’s daughter.

Later his parents bought his father’s home ranch only three miles away, so all through his growing up years “the bison herds were visible as dark patches on distant hills,” according to memories he recorded in his book.

By age ten, Lott recalls that Big Medicine was occasionally turned out in the larger pasture, and contended in battle with other big herd bulls for a time.

Big Medicine spent most of his life in a rather small pasture with a few cows, where he could be easily seen by visitors, and was said to be the most popular tourist stop in Montana after Yellowstone Park.

However, he was soon returned to the smaller pasture with a few cows, which was less stressful for him.

Not a true albino, Big Medicine’s eyes were blue and a thick knot of brown hair grew between his horns.

Nevertheless, it was quite clear that his herd had the true albino genetics.

Alaskan buffalo herd birthed White calves

In 1928, before Big Medicine was born, it was decided to start a new federal herd of Plains buffalo in Alaska to replace the Wood buffalo which had become extinct there.

Twenty-three buffalo cows and bulls from Big Medicine’s home on the National Bison Range were transplanted to Delta Junction, Alaska, to start a new free-roaming herd.

Some in the new Alaskan herd must have carried the same genetics for albinism that Big Medicine did when born five years later—because rare white calves began showing up in that herd.

But since it was rugged and remote forested country, mostly without roads, it was difficult to follow-up on them. Living in thriving wild herds in spectacular mountain country often in snow, the rare white calves in Alaska were difficult to check up on or see from the air.

Also, they lived among large predators such as packs of wolves, fierce grizzly bears and mountain lions—so they were extremely vulnerable. About half of calves did not survive their first yar.

The first Alaskan white calf was born in 1939 and another the next year. They were seen together several times, but then disappeared. In 1949 a white calf was killed by a truck on the road.

In all, 12 white buffalo calves were sighted in the half-wild Alaskan herds over the next 50 years, according to David Dary, author of The Buffalo Book. One had a brown top knot on his head, as did Big Medicine.

Apparently, none survived as long as age three.

Many of the calves seen were recorded only through brief sightings from an airplane.

Game wardens tried to capture the last calf, sighted in the fall of 1973, planning to keep it for special care in a smaller enclosure or zoo. But it disappeared and was not seen again.

Alaskan wildlife officials say no white buffalo were sighted for the next 44 years among the 500 Plains buffalo living in the 90,000-acre Delta Bison Sanctuary.

However, the genetics that can result in white hair probably still exist in the bison herd, Bob Schmidt, of Alaska Fish and Game, told me in 2016. They just needed the right combination of genetics for it to happen.

“If both parents had the recessive gene there would be a 25 percent chance that their offspring would be white,” he said.

White calf born in Alaska herd in 2017

Apparently it happened. Amazingly, the very next year on May 9, 2017 another white calf was spotted in a remote area of the Farewell Bison Herd near McGrath in Alaska.

A white calf born in the Farewell Bison Herd near McGrath, Alaska, in the spring of 2017, is photographed by Josh Peirce and his wife Kellie from the air. He sighted the calf several times in June from an airplane, judging it healthy and estimating its age at three months. But, unfortunately it was not seen again and was believed to be the victim of wolves. Photo by Kellie Peirce.

Josh Peirce is the Alaska Wildlife Biologist with the State Fish and Game based in the McGrath community.

By this time the Delta herd had been split into four herds of plains bison in Alaska, all of them descended from the 23 head shipped from Big Medicine’s home on the National Bison Range in Montana in 1928.

Peirce says the unfenced home range for the bison covers about 500 square miles and has no roads, only an airstrip where planes can land.

“It’s fair to say the herd is at a record high now,” Peirce reported. “There are 395 adults, 115 calves, a total of 510 animals.”

Peirce’s job includes getting a count of the buffalo each year and making plans for the annual spring and fall hunts of excess animals.

The Farewell area is about 225 miles northwest of Anchorage on the Kuskokwim River and 60 miles southeast of McGrath, in the foothills of high rugged mountains,

Peirce says the white calf was seen as early as May 9 and he saw it several times in June, and estimated its age at about 3 months. It appeared to be in good health, he said, was able to keep up with the herd and seemed to have good eyesight.

The Alaskan buffalo herd is always on the move, often covering 20 to 30 miles a day, so it would be difficult to follow one small white calf, especially in deep snow in winter from the air.

However, this latest calf apparently didn’t make it until snow fell in the fall.

Peirce says the little white calf was not seen again. He believes it—like so many other buffalo calves, as well as baby moose—fell to some of the many large predators hunting in the area, likely a pack of wolves.

Only 40 to 60%—or half—of all buffalo and moose calves survive their first year, he said.

If they make it through their first summer—they still risk the extreme cold and threat of starvation in wintertime—which take a toll of very young and very old animals.

The Alaskan buffalo are not fed or watered, summer or winter.

Peirce suspects the missing white calf is leucistic—not a full albino.

In the photos he and his wife Kellie shot, the calf appears to have a dark ring around its eyes and a light brown “cap” on its head, he said.

Alaska Fish & Wildllife News, in announcing the rare birth in Aug 2017, describes two genetic variations: Albinism and Leucism.

“Albinism and leucism are both conditions that can cause an animal to have white fur, hair, skin or feathers. Both are caused by a reduction of pigments at the cellular level, and are usually genetic, according to the article.

“Leucism can affect an entire animal, or just patches (animals with partial leucism are referred to as “pied” or “piebald”) and a leucistic animal will have normal-looking eyes. Animals with albinism have pink eyes.”

Rarity of White Genetics

“Albinism is the complete absence of tissue pigment. Albino can just happen—it doesn’t have to be genetic,” says Schmidt. There are many types of albinism, all of which involve lack of the pigment in varying degrees that gives color to the skin, hair and eyes.

Albinism and its related conditions are often associated with eye problems and more susceptibility to sunburn and skin cancers.

“As a general rule, albino animals have low survival rates,” he says.

“White buffalo . . . don’t seem to do well,” agrees Lott. “Far from going forth and multiplying, they dwindle and disappear.”

He says white can be a good winter color for animals such as rabbits that turn white in winter to blend with snowy background, thus making them safer from wolf attack.

“But probably not for buffalo calves. . . . the answer [to their poor survival rates] probably lies in winter.

White Cloud, mother and grandmother of two white calves and a pure albino, lived most of her 20 years in a small buffalo herd at the National Buffalo Museum in Jamestown, North Dakota. Her coat brushed to a beautiful sheen, she is now on exhibit at the museum there. Jamestown Sun.

“The normal dark coat may be a lifesaver in winter. Bison seldom if ever die of heat, but they often die of cold…Bison evolved in really terrible winters; and even now, especially severe winters kill many of the old and the young.”

Another rare genetic condition causes a buffalo to be born white, but to turn brown within a year or two as it matures.

Finally, a “white buffalo” may actually prove to be what is now called a beefalo—a cross between buffalo and white cattle, such as Charolais.

Don’t be fooled by this in a tourist trap, warns author Steven Rinella in his book American Buffalo: In search of a lost icon.

Rinella says that many so-called “sacred white buffalo . . . a fixure of Western tourist traps, are the result of crossbreeding between buffalo and white breeds of cattle.”

All the plains buffalo in Alaska’s four herds are descendants of the 23 animals obtained from the National Bison Range in Montana before any cattle genes were introduced into the herd.

So Alaska bison are among the relatively small number of genetically pure bison. Any of them might have the genetics of Big Medicine.

Native Excitement brings Welcome

Wherever a white buffalo calf appears, Native people come to welcome it, to celebrate and honor its birth.

They regard a little white buffalo calf as good news, a sign of peace and harmony—and of good times to come. They affirm it symbolizes spiritual renewal and the hope of bringing people of all backgrounds closer together.

As a calf—and later—Big Medicine was welcomed and honored by Native Americans as a highly spiritual animal—a sign of peace and harmony, and of good times to come. Montana Historical Society.

“A white buffalo is the most sacred living thing you could ever encounter,” according to John Lame Deer, a Lakota spiritual leader.

They give thanks, with perhaps a smoky smudge of lighted sweet grass and songs to the beating of a drum.

Elders ensure the proper ceremonials and rituals are followed in showing respect to this highly spiritual animal.

“It will bring about purity of mind, body and spirit, and unify all nations—black, red yellow and white,” says Floyd Hand Looks For Buffalo, an Oglala Medicine Man from Pine Ridge, South Dakota.

Some cultures see the white buffalo as a manifestation of the White Buffalo Calf Maiden, long revered as a prophet.

Often visitors leave gifts of tobacco, colored scarves and dream-catchers at the site.

White Buffalo Lore

Historically many Indian tribes considered the white buffalo and a white buffalo robe to have special powers.

Whenever spotted in a wild herd, a white buffalo was the most likely to be killed. It was said they were so highly desired that few lived more than a few years.

William Hornaday in his Smithsonian review reported in 1887 that he had “met many old buffalo hunters, who had killed thousands and seen scores of thousands of buffalo, yet never had seen a white one.”

“Albino buffaloes were always so highly prized that not a single one, so far as I can learn, ever had the good fortune to attain adult size, their appearance being so striking, in contrast with the other members of the herd, as to cause their speedy destruction,” he wrote.

“From all accounts it appears that not over 10 or 11 white buffaloes, or white buffalo skins, were ever seen by white men. Pied individuals [with various spotted patterns] were occasionally obtained, but they too were and are rare.”

In the old days, a set religious ceremony attended the skinning and tanning of a white robe.

A white robe brought great honor to its owner and he kept it in a special place of honor in the tepee, a possession beyond price. If willing to sell or trade or give away, he might cut it in pieces—even a small piece was a “sacred article,” worth a horse or more in trade.

Blind, deaf calf is born

In 1937, Big Medicine sired a full albino bull calf, with pink eyes and white hooves, born to his own mother. Unfortunately, the calf was both deaf and blind.

At the age of 6 months, this calf was sent to the National Zoological Gardens at Washington, DC, upon request. He lived there in the National Zoo on public display several years—perhaps as long as 12 years, according to one report.

Lott said his grandfather “with the directness of the stockman and veterinarian that he was . . . intended to try for more … but the bureaucrats above him—wisely, I think—decreed that the US Fish and Wildlife Service was not in the business of producing freaks of nature.”

That blind buffalo died from what ranchers commonly call “hardware disease”—a length of baling wire lodged in his stomach from the hay he ate. Or he died from an infected cut on his leg. Lott said when his family asked about the cause of death, they were given both answers by staff at the National Zoo in Washington.

Popular Montana tourist stop

In his prime, Big Medicine weighed more than 1,900 pounds, rose 6 feet tall at the hump, and measured almost 12 feet from the tip of his nose to the end of his tail.

There he became, it was said, the second most popular tourist stop in Montana, after Yellowstone Park.

Out on the bigger range by age ten, he contended in battle with other big bulls for a time before returning to the smaller pasture. He became a herd bull, and sired numerous offspring.

On the range a bison’s natural life span is about 15 to 20 years, with their teeth becoming greatly worn with use.

For this reason, Big Medicine spent much of his maturity in the Bison Range’s smaller display pasture.

He was often seen standing on a clay knob overlooking his group of buffalo cows.

Big Medicine died at age 26, was mounted and is now exhibited at the Montana Historical Society museum in Helena.

Big Medicine died on August 25, 1959 at the age of 26, old for a bison bull.

At that time, he weighed only 1,193 pounds. His hide was in poor condition due to his advanced age.

He was mounted in a full body stance and now stands in exhibition at the Montana Historical Society museum in Helena.

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog

Comprehensive and very educational!

Thanks Dean, good to hear from you. I’m missing the white buffalo in Jamestown. But it’s good to see White Cloud mounted and brushed in the National museum there, isn’t it? Francie