At the center of the Northern Plains is a rugged section of Badlands, buttes and fertile grasslands, where buffalo, cattle and sheep graze, and deer and antelope still roam.

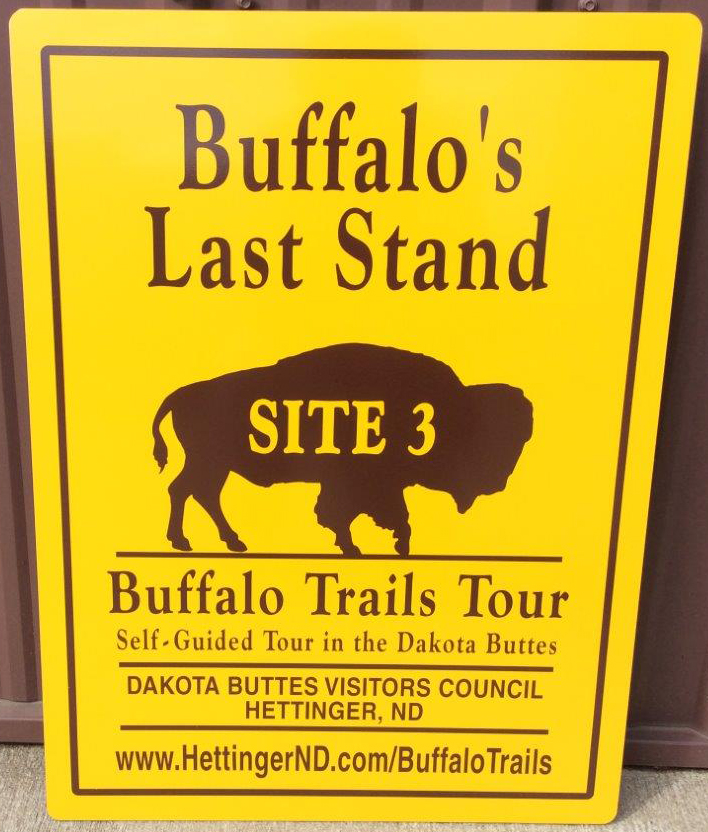

We’d love to have you join us on the 10-site tour we’ve put together of the last great hunts and other historic and contemporary buffalo events, each clearly marked by a yellow sign.

These sites include three of the last great buffalo hunts, including the valley of the last stand—the final harvest of the last 1,200 wild buffalo by Sitting Bull and his band on October 12 and 13, 1883.

At the center of these events are previously untold stories and authentic, unspoiled places to envision where they took place.

This region, bordered by the North Dakota towns of Hettinger, Reeder and Scranton, and the South Dakota towns of Lemmon, Bison and Buffalo, is where Native people conducted the last traditional hunts of the majestic wild buffalo that once roamed here in huge herds on what was then the Great Sioux Reservation.

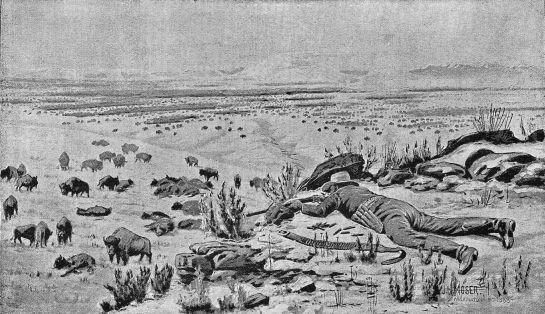

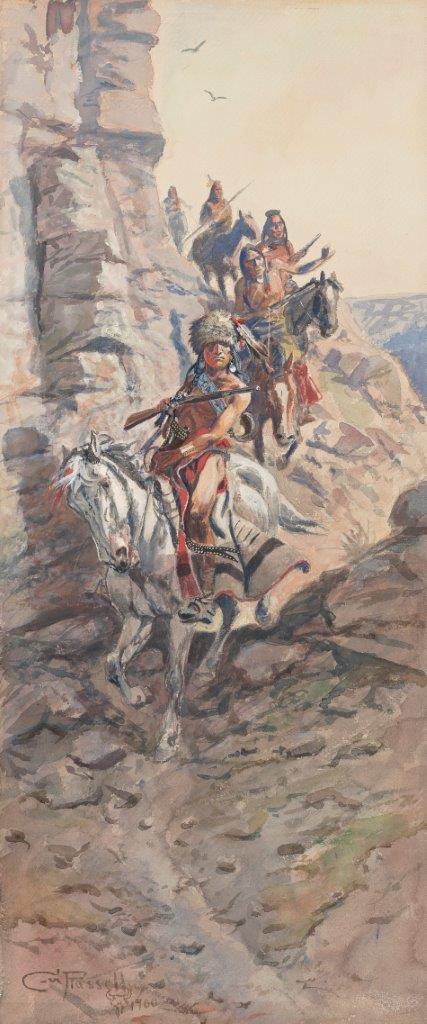

The Self-Guided Tour includes three of the Last Great Buffalo Hunts including the final harvest of 1,200 buffalo by the Sitting Bull band in 1883. Painting by CMRussell, Amon Carter Museum.

The history of the last buffalo hunts you’ll find here is true and documented from primary sources. Although not widely known until recently, it is told in detail by people who were there on those hunts.

They are traditional Native American hunts that somehow fell through the cracks of U.S. history.

Often showcased is the shameful history of the buffalo’s final days as a wasteful slaughter by white hide hunters.

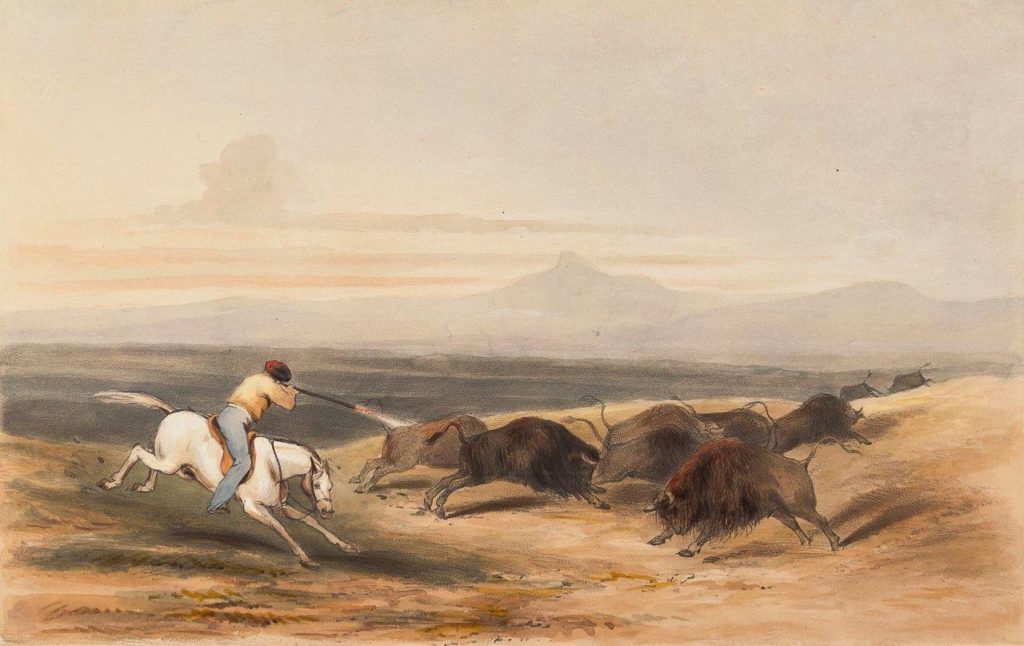

White hide hunters slaughtered huge numbers of buffalo with powerful guns, in what was called a stand—often a single shooter hidden from sight, killing any leader who attempted to run. Illustration from Wm. Hornaday’s 1889 book “The Extermination of the American Bison.”

That happened, of course. But it is not the whole story.

Instead, the first-person recollections from these final hunts bring together a heroic saga befitting the noble beasts themselves.

It features Native Americans, who followed time-honored religious traditions in planning and preparing for each hunt, following through, caring for the meat—and never failing to give thanks for their success.

And then, just before the last wild herds disappeared forever, one Native American family returned to the hunt site to save 5 orphaned buffalo calves—and became internationally famous for nourishing their own herd.

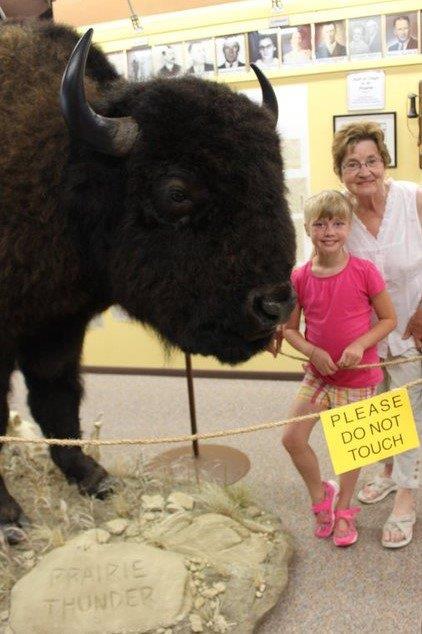

Included on the tour are Prairie Thunder, a full-size mounted buffalo at the Dakota Buttes museum, and an authentic buffalo jump at Shadehill, S.D, used for thousands of years—long before hunters had the luxury of horses and guns.

In no other place in the world can you find the history of all these events brought together.

Here all parts of the Buffalo story come together. From ancient times until now, when nearly every Indian Tribe in the Plains owns their own tribal buffalo herd and are delighted to share it with you.

Visitors can plan their Buffalo Trails jaunt from anywhere in the world via online connections.

So if you’re a traveler smitten by the iconic American buffalo, you can plan your next trip around buffalo sites you find here and on our website. We outline world class trips to visit buffalo-related sites, both historic and modern day.

North Dakota Tourism has added our Buffalo Trails Tour to its Best Places and pitches it with international tours. South Dakota Travel provides links as well. (This information is available in our Self-Tour Guide “Buffalo Trails in the Dakota Buttes” available at local businesses and hettingernd.com/buffalotrails.)

Site 1. Prairie Thunder—Dakota Buttes Museum

Our tour begins with a closeup of America’s New National Mammal—the magnificent bison or buffalo—in the Dakota Buttes Museum in Hettinger.

Prairie Thunder represents the last wild herds that came here in their final days, the last great traditional hunts, the miracle of how a handful of men and women, including local Native Americans, saved the buffalo from extinction, and buffalo herds that graze here today. Photo by Bonnie Smith.

Meet Prairie Thunder, our majestic full-mount buffalo—harvested in early January during a 20 below zero cold snap when his deep brown winter hair had grown to its finest thickness.

The buffalo has long captured the imagination of people everywhere, with his great size and stature, confrontational eye, beautifully-shaped black horns and semi-tragic history.

William Hornaday of the Smithsonian Museum probably described him best back in 1887:

“The magnificent dark brown frontlet and beard of the bison, the shaggy coat of hair upon the neck, hump, and shoulders, the dense coat of finer fur on the hindquarters, give the bison a grandeur and nobility of presence which are beyond all comparison amongst ruminants,” he wrote.

None, he declared, is as striking in appearance– as the male buffalo.

“The grandest of them all,” he summed it up.

Both bulls and cows are intimidating figures, but the buffalo bull is larger, tall and massive, strangely narrow in profile, with shoulders broader than his slim hips—all accented by the large shoulder hump.

His hair hangs long and heavy over the front quarters, a “thick mass of luxuriant black locks,” with even longer hair over forehead, beard, mane and chaps of the forelegs, but short and sleek over the rear and tail. Some bulls have long beards.

Typically, Prairie Thunder stands in the front exhibit hall of Dakota Buttes Museum to greet visitors.

He stands 5.5 feet high at the shoulder and is 8.5 feet from nose to tail. In life he was judged to weigh nearly 2,000 pounds. His hair varies in length from 3.5 to 5 inches. His horns span 30 inches at their widest point.

Given this area’s close connection to the last buffalo hunts along with contemporary buffalo ranching, the Hettinger community launched a two-year fundraising effort to acquire Prairie Thunder.

Donated by a local rancher, this beautifully preserved buffalo made his debut in the museum on July 4, 2010.

Prairie Thunder represents to us, not only those last wild herds and the great traditional hunts, but the miracle of how a handful of men and women, including Native Americans, saved the buffalo from near-extinction.

A major event in that rescue occurred in this area, as well, when Pete Dupree and his brothers drove a buckboard wagon to the last buffalo ranges and took home five husky, healthy calves to grow and multiply on the Great Sioux Indian Reservation.

Before long Pete Dupree counted his herd at 83 head.

This buffalo mount was created by national award-winning taxidermist Randy Holler, of Hettinger, who worked 18 months to complete the work, donating much his time and artistry to the museum project.

Visitors are asked not to touch Prairie Thunder, his coat brushed to a rich sheen, as he stands in Hettinger’s Dakota Buttes Museum. Photo by Wendy Berg

His coat is unusually rich and beautiful, and the oils from human hands can destroy his natural sheen, so we ask you please to refrain from touching Prairie Thunder.

Knowing visitors enjoy the luxurious feel of a genuine buffalo hide, the museum staff provides a separate buffalo robe nearby, which you are welcome to touch and handle. (More on the magnificent buffalo is found in Chapter 5, page 76, in “Buffalo Heartbeats Across the Plains,” the companion book to our Self-Guided Tour booklet “Buffalo Trails in the Dakota Buttes,” both available at local businesses and hettingernd.com/buffalotrails.)

Site 2. Hiddenwood Hunt—June 1882

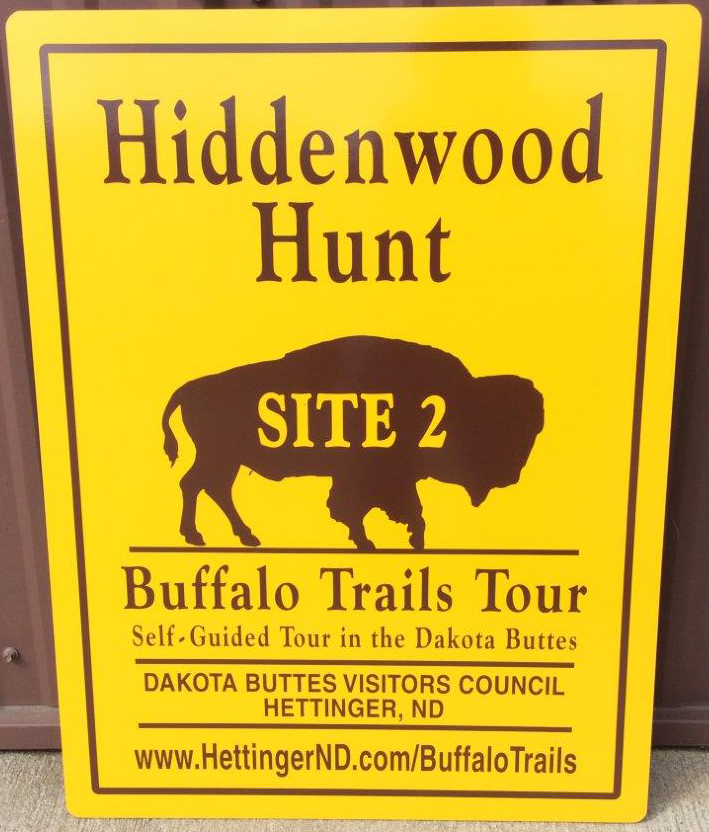

Sites on Hettinger’s Self-Guided Tour are identified by yellow markers—Site 2 is the Hiddenwood Hunt. FM Berg.

As Running Antelope—leader of the hunt—Long Soldier and other prominent men rode out on a high point, just out of sight, they saw what they thought never to see again: thousands of buffalo grazing across valley and hills.

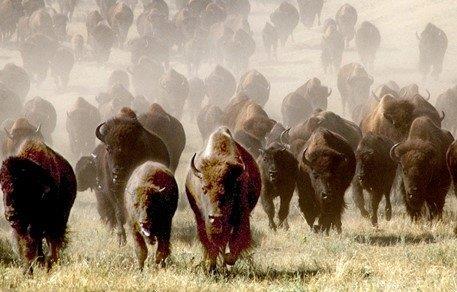

Thousands of buffalo grazed across Hiddenwood valley and hills in June 1882. Photo courtesy of South Dakota Tourism.

Only a few hundred yards off stood the nearest buffalo. So close they could hear him grunt and snort. With the wind in their faces, they smelled his rank odor.

With the wind in their faces the hunters could smell the bull’s rank odor. Photo SDT.

They waited. It was important that all hunters start at the same time and all have an equal chance before the herd began to run.

Look off to the east in the direction of Fort Yates, to your left. This is where most of the hunters from the Great Sioux Nation were coming from, riding low and quiet up Hiddenwood Creek.

Running Antelope—leader of the hunt—Long Soldier and other prominent men rode out on a high point, just out of sight, as they waited for other hunters to join them. Painting by CMRussell, ACM.

Another group of this band rode farther north. They had not yet caught sight of what was ahead, what their scouts told them was here.

Since boyhood the older men had hunted buffalo in this place. But for the past 15 years these prime Dakota grasslands had stood empty.

White hide hunters had relentlessly pushed the buffalo farther and farther west. Now most herds were gone forever—killed off for their hides.

Then mysteriously, this very last big herd of 50,000 came back.

Miraculously, the last big herd of 50,000 buffalo returned to the Standing Rock Sioux reservation in 1880. Photo SDT.

“On the wings of the wind came the news that Pte, the buffalo, had arrived to make a Sioux holiday and provide such meat as had never been furnished even by the most conscientious and liberal of beef contractors,” wrote James McLaughlin, Indian agent at the Standing Rock agency in Fort Yates, who rode along on this hunt.

The winds told tribal elders the mission of the buffalos’ return.

The buffalo returned to provide their starving Lakota brothers and sisters with desperately needed food, clothing and shelter before all were killed by the white hide hunters. That’s what the elders for told.

The large hunting party of 2,000 men, women and children left Fort Yates, 100 miles to the east, on June 10, 1882, moving slowly.

Six hundred hunters rode horseback. Others rode in horse-drawn wagons or travois pulled by horses or dogs. Many walked.

“It would hardly be possible to make a more glittering array of a body of Indians,” wrote McLaughlin in his book, My Friend the Indian. “The plains of Dakota had not for many years seen so resplendent a gathering of these people as that which moved out of Standing Rock just after dawn.”

During 10 days of travel to the famous hunting campground at Hiddenwood—where scouts assured them they’d find buffalo, the hunting party paused for traditional religious ceremonials and prayers for a successful hunt.

You are standing on a historic spot. This is where “The Last Great Buffalo Hunt” began on or about June 20, 1882, in this broad fertile valley near Hiddenwood Cliff.

Let’s imagine this valley as it was on that delightful June morning in 1882, filled with an immense herd of buffalo. The big animals grazed peacefully on both sides of Hiddenwood Creek and off into the distance, spread out over the broad valley and hills.

Buffalo cows nuzzled and nursed their young calves. Tawny-colored calves frisked and played together.

Massive bulls stood down by Hiddenwood Creek in the mud, drinking, pawing and splashing. Some tore into the yellow clay of Hiddenwood Cliff with huge shaggy heads, throwing up dust and rubbing their rough winter pelts.

To the right, up a draw, big bulls rubbed themselves in a buffalo wallow. Awaiting their turn, several squared off, whacking heads and horns, grunting and pawing up the ground.

Planning their approach to the herd before them, Running Antelope and others gestured and talked in whispers, as they waited for the others to come up on the high point. All gasped as they rode up and glimpsed the valley below and the hills on either side filled with buffalo.

Quietly, feverishly, they spread out along the flanks. These were people with buffalo hunting running in their veins and in their hearts.

Since childhood they heard stories of courage on the hunt, deeds of strength and endurance against great bulls, of buffalo mystique and legend. They lived in buffalo hide tepees, slept under soft buffalo robes, ran through cactus in tough hide moccasins, delighted in eating pemmican and dried buffalo meat.

Older Lakota men had hunted here before. This was an ancient campground for buffalo-hunting plains tribes. For hundreds, perhaps thousands, of years the cliff and creek winding below it were known as Hiddenwood (Pha Can Nahma)—because the trees could not be seen from a distance. Tepee rings filled this valley when first settlers arrived.

Tepee rings filled Hiddenwood Valley when the first settlers arrived. Painting by CMRussell, ACM.

The horses felt the excitement too, lifted their heads, snorted, pranced and reared.

Running Antelope glanced back at the hunters lined up just below the crest of the bluffs and across the creek on the far slope. Every eye was on him, all ready to go.

He lifted his arm and drove it forward in a forceful gesture.

And–they were off!

The hunters charged at full speed, dashing among the buffalo as they attacked from the hills on both sides of Hiddenwood Creek.

Wolves slashing viciously at the throat of the old lone bull turned suddenly and streaked out of range over the ridge, looking back as they ran. A few antelope, grazing on the flat, leapt up a side hill and turned to stare curiously, their sharp eyes alert.

Rifles cracked and buffalo fell. Some began to run. Riders with fast horses raced ahead, cut in close to turn the leaders and dropped them with a bullet or two.

The buffalo turned in confusion, confronting their attackers with furious thrusts and slashes of massive heads and horns. They grunted, bellowed and flung their short, stubby tails over their backs.

Each hunter rode close alongside his buffalo and shot it in the heart or lungs—just ahead of the front leg. Usually the animal fell with one shot. No bullets wasted. He made sure it was dead and raced ahead for another shot.

Buffalo on distant slopes merely looked up and returned to grazing.

Most of the men carried repeating rifles, breechloaders—which fed bullets from the rear rather than the front of the barrel, allowing faster reloading.

Not all the Indians could afford guns. Some older men and boys, in their poverty, used only bow and arrows.

A few others had no guns because McLaughlin did not trust them enough to allow weapons. Many of these same hunters had fought against Custer and the 7th Cavalry at the Battle of the Little Big Horn, only a few years earlier.

Wolf Necklace, an old man of about 60, was one hunter without fire power. He carried only bow and arrows, rode an old gray pony and followed a buffalo whose side he had pierced with four or five protruding arrows. As his pony walked slowly alongside, he now and then shot another arrow, but without the arm power needed to bury them deeply.

A friend rode up with a pistol and offered to help.

“No. Don’t shoot!” cried Wolf Necklace. “The arrows will work in and he will die.”

He was right. After a few minutes the big animal fell dead. Wolf Necklace had killed it with no help from anyone.

The hunters rode their best horses, swift runners—older seasoned “buffalo horses” if possible. Men with younger horses worried that, though fast, they might fail to perform in close quarters alongside these strange, pungent-smelling beasts that they’d never encountered before.

Indeed, from the first charge, plunging, rearing horses could be seen through the valley as riders struggled to gain control.

It was a long and successful day. There was no rest. The hunters kept up the slaughter until they lost their horses or were exhausted.

Not a few ended the chase on foot. No attempt at butchering was made that first day.

Women cooked humps and other tender morsels and fed the hunters who returned to camp long after dark. All were too tired that night for celebrating or storytelling.

On the second day the people butchered and cared for the meat.

All knew their tasks. The men skinned, quartered the animals and hauled the meat in to the new camp by travois, pack horse and wagon.

Women began the formidable task of slicing chunks of meat into thin sheets for drying. These sheets they hung on willow racks to dry in the sun.

When cured, they’d make and store the meat as pemmican and jerky. They stretched the hides and staked them on the ground to dry. As summer hides lacking prime winter hair, they’d be used for rawhide and tanned leather—without hair, for clothing, moccasins, tepee covers and many other uses.

That evening after the day of butchering everyone feasted. It was a feast such as had not been held for many years.

There was dancing, singing and storytelling. Great orators and chiefs like Gall, John Grass, Crow King, Rain-in-the-Face, and Spotted Horn Bull recounted tales of courage, fortitude and tragedy in hunting and battle.

McLaughlin said, “The head men of the Sioux Nation were on that hunt and at peace on the banks of Hiddenwood Creek that night.”

On the third day the hunters ran buffalo again a few miles farther west. The herd had not moved far. That day they killed 3,000.

Then they made camp at several places on water, butchered and hung the meat to dry in the hot sun. McLaughlin said they had killed many and yet showed restraint.

“I never have known an Indian to kill a game animal that he did not need,” he wrote. “And I have known few white hunters to stop while there was game to kill.”

It was McLaughlin who called this the “last great hunt” in his memoirs, written years later.

Today this historic site marks the Hiddenwood Hunt, named for Hiddenwood Cliff across the green valley, at upper right in this photo. Image by Kathy Walsh

While it wasn’t quite the last hunt of the huge wild herds—that happened about a year later—it was indisputably the largest of the last hunts, both in number of people involved and size of the harvest.

Two thousand Native Dakota Sioux in traditional dress came on the Hiddenwood hunt and in two days they killed 5,000 buffalo, relying on ancient religious ceremony and tradition throughout. (For more details see Chapter 1. The Great Hiddenwood Hunt, page 10, in the companion book “Buffalo Heartbeats across the Plains,”)

In June 1882, 2,000 Dakota Sioux travelled 100 miles from Fort Yates to the Hiddenwood Hunt, and in two days killed 5,000 buffalo. Colored area on the North and South Dakota map shows where this last hunt occurred. Photo by FM Berg.

This valley at Hiddenwood Cliff was also where General George Custer and his 7th Cavalry soldiers made camp on July 8, 1874 on their journey to the Black Hills from Ft. Abraham Lincoln at Bismarck—a few years before this last great buffalo hunt took place.

Site 3. Sitting Bull Hunt—Buffalo’s Last Stand

Take a deep breath of the fresh, clean air! Stretch, look around and let your imagination flow!

Site 3, The Buffalo’s Last Stand—the Sitting Bull hunt finished off the last big herd. Vic Smith, well-known hide hunter said, “There was not a hoof left. That wound up the buffalo in the Far West, only a stray bull being seen here and there afterwards.” FM Berg.

Stop on the high point and hold your breath for a stunning view. A spectacular panorama suddenly opens out ahead and you can see for miles in every direction.

This is where the American buffalo made their last stand—in this remote and beautiful valley and others like it within perhaps 30 or 40 miles.

This breathtaking vista looks today much as it did 140 years ago when the last buffalo returned here “to provide for the sons and daughters of the Lakota…” The air is light and clear, outlining each butte. Photo by Kendra Rosencrans.

In the distance you see long ridges stretching across the horizon from west to east in waves, each wave is a long divide of peaks, plateaus and flat-topped buttes splashed with shades of violet, lavender and blue. Each successive wave takes on a paler shade as it recedes into the background.

This breathtaking vista looks today much as it did when the last buffalo returned here after an absence of 15 years “to provide for the sons and daughters of the Lakota…” in the words of Indian Agent James McLaughlin.

The air is light and clear, outlining each butte, however distant. A reporter riding through here with Custer the next day after camping at Hiddenwood judged he could see “no less than” 40 miles.

“The well-defined, sharpened lines projected on the sky by rolling prairies and distant buttes is marvelous beyond expression, and can never be appreciated unless actually seen. The outlines seem cut in relief upon the very face of the heavens,” he wrote.

But that reporter saw no buffalo—because all had retreated farther west when he rode through in 1874.

Amazingly, in a few years, this last big herd of buffalo returned, and they survived here for nearly three years.

Maybe we can visualize that too. Hundreds and thousands of buffalo streaming into this valley from the west, led by determined matriarchs in large and small scattered herds.

Some herds would have turned off from the larger migration upon finding a draw or buttes to their liking. They spread out and began to fill in the entire vista as far as we can see.

The southern herd was long gone by this time—from Kansas, Colorado and Texas—mainly they disappeared by 1875 from heavy hunting.

The last remnant of the great northern herd had migrated to the Miles City area of southeastern Montana and then split at the Yellowstone River. Half crossed the river and went north into the waiting rifles of hundreds of hunters, both white and Indian.

Most were annihilated within the year.

This other half—an estimated 50,000, the last of the last great wild herds—came east into this remote part of Dakota Territory, then called the Great Sioux Reservation, now part of Perkins County, South Dakota.

For the buffalo it was a land of relative safety for a time, forbidden to white hide hunters.

The area is rimmed with buttes. The reporter riding with Custer wrote of them:

“The view is fine indeed. . . Buttes . . . of all shapes—conical, sugar-loafed, pinnacled, dome-topped and flat-topped, and all girdled by belts of as varying and blended colors as the strata of white, black, blue, brown and red clays and sandstone of their naked sides”

The rivers here flow east to the Missouri River. Ahead, just out of sight runs the North Grand River, separated from the South Grand by a high divide, and still farther south by the ridges and divides of the forks of the Moreau River, their peaks rising into the distance.

Closer in, the peaks, cutbanks, rugged cliffs, wooded draws, gullies and eroded, rock-crested buttes cut through prairie grasslands. Green in spring and early summer, curing to a nutritious golden brown by fall.

A variety of plants grows here. Nutritious, high-protein grasses—buffalo grass, blue gramma, native wheat grass.

Prairie flowers bloom and wave in the wind—tall golden sunflowers, fragrant sage, yucca, wild mustard, pink coneflowers and prickly pear cactus lush with large and delicate lemon-yellow blooms, and Indian turnips highly prized by Native women who dug them in these hills to balance their diet high in wild meat.

A golden eagle nests atop a high rocky outcropping. Grouse and wild turkeys rustle through long grass. The liquid melody of the meadowlark floats on the air, along with songs of the horned lark and lark bunting and other prairie birds that nest on the ground.

A jackrabbit springs by on powerful legs and a mule deer grazes out in the open with twin fawns, while a whitetail doe hides in a wooded draw. Antelope run up a side hill.

We call this the Butchering Site because of the many buffalo bones found here. The leg bones we’ve found are chopped in half to remove the marrow, in the ancient Indian manner. They still show up in sandy banks after a hard rain or snow runoff.

Powerful buffalo leg bones found here have been chopped in half to remove the marrow, in the ancient manner. They still show up in sandy banks after snow runoff. FM Berg.

Off to the left, trees mark springs on a side hill where hunting parties left evidence of their camps.

Native men deftly skinned the carcasses, cut and loaded meat onto pack horses for hauling in to camp, leaving skulls and some of the larger bones where they fell.

Women sliced meat thin and hung it in sheets on willow frames to dry in the sun. The hides they stretched and staked out on the ground near their tepees.

Above, soaring hawks and turkey buzzards took note.

Like the Hiddenwood site, many ancient hunts took place here, probably for thousands of years, as well as these final ones between 1880 and 1883.

Many ancient hunts took place at “The Last Stand,” probably for thousands of years. It’s been called the Butchering Site, because of the many buffalo bones and skulls found. CM Russell, ACM.

The rich heritage of nomadic tribes hunting these grasslands left behind tepee rings, arrowheads, tools and beads, as well as buffalo bones. Petroglyphs are found on a peak in the distance at left center.

Famous Indian chiefs lived and hunted here in these badlands and grasslands—Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, Gall, John Grass and Rain-in-the-Face—were all here. Early day explorers and trappers came too—Hugh Glass, Jim Bridger and General George A. Custer with the 7th Cavalry.

We can imagine herds of buffalo grazing here and there into the distance, while in the foreground a successful Indian hunting party butchers and cares for their meat.

If you see black or red Angus cattle in this pasture it’s easy to imagine them as buffalo from long ago.

At a distance, buffalo show up as more wedge-like in silhouette than cattle. High at the hump with large hanging head, their elevated forequarters sloping down to small narrow rears.

In contrast, distant cattle appear squared off, as boxlike rectangles. Horses look more rounded in their hips.

Listen—and you might hear Indian drumming on a stray breeze.

Not much is known of the buffalo hunts during those last three years, other than the two hunts documented by the missionary Rev. Thomas Riggs and Indian Agent James McLaughlin, and William Hornaday’s comments on the final Sitting Bull hunt. Only a few other hunts were briefly mentioned in newspapers and in McLaughlin’s letters.

We know these last 10,000 buffalo were set upon by numerous Native hunts during that time, both large and small. Legions of white hide hunters lurked at the reservation borders making illegal forays inside when they dared.

For nearly three years the buffalo stayed here, dwindling—yet thousands remained—until finished off the fall of 1883 by the Sitting Bull Hunt.

Many thousands of Native Americans were ensconced here on the Great Sioux Reservation. McLaughlin reported that his agency alone had charge of nearly 6,000 people, and there were a number of other agencies on this vast reservation that included most of the western half of South Dakota.

With a great many hungry people, we might wonder how the buffalo lasted so long—even in these rugged badlands.

Why were they not quickly hunted to extinction, as elsewhere?

The answer probably lies in what hunting was allowed, rather than lack of desire to hunt them.

Indian Agent James McLaughlin, who was assigned to the agency at Ft Yates and arrived the end of 1881 ran a tight ship. Determined to stay in control, he did not necessarily grant permission to Lakota hunters who wanted to pursue buffalo here, a hundred miles away from where they lived.

Punishment for disobeying an agent’s rules could be severe, including cutting family food rations.

For the Sioux Indian people assigned to live here this was an especially difficult and painful time.

A nomadic, independent people with the knowledge and skills for survival in an unforgiving land, they traditionally cared for themselves and their families with no help from anyone. Now, without buffalo, they could no longer care for their families or travel freely.

Only a few years earlier, these same Sioux bands had fought and won the Battle of the Little Big Horn, along with their allies the Northern Cheyenne.

They paid a heavy price for that victory, assigned to specific agencies of their reservation.

Almost immediately after that victory, their large reservation was reduced in size. They lost their beloved Black Hills and a western strip of land equivalent to the width of one county—from 104 to 103 degrees of latitude.

Federal policy in Washington, DC, decreed that Natives should build log cabins, take up farming and replace their spiritual traditions, cultural values, religion, language and even life ways with those of mainstream America.

Promised food rations often came up short as thieves and dishonest agents sold much of their intended food and blankets. Unfamiliar diseases hit, such as smallpox and measles, sometimes fatally for whole Indian families with no natural immunity to them.

Many children were sent to far-off boarding schools in New England—Connecticut and New Hampshire, even for years—to learn the ways of white people. Some children died there. Most were terrified and miserable in a strange land.

The great Lakota horse herds and guns were gone.

During those three years, it seems the Lakota people needed to request not only a hunting permit from McLaughlin, but sometimes ammunition and guns.

Fortunately, families were allowed one or two horses for farming and perhaps a rifle, as they were expected to produce food for themselves.

And yet—these valleys suddenly teemed with buffalo. For many years the Native people had known what it was like to live without them. Now the knowledge of buffalo grazing across these native pastures must have brought great joy to their hearts. Their beloved buffalo had returned when so desperately needed.

McLaughlin felt sympathetic to the plight of his charges. Newly arrived at Ft. Yates in September 1881, he spoke Sioux as learned from his wife, a Minnesota Sioux, and his long tenure at the Devils Lake Reservation.

Yet he enforced rigid and often unworkable decisions made in Washington. There was great fear there and among western settlers of a Sioux uprising. McLaughlin was determined that would not happen.

The Great Sioux Reservation was still very large during this window of time. Between 1876 and 1889 it extended approximately 130 miles wide by 230 miles north and south. The Indian agencies were connected within the reservation. However, the Lakota people were assigned to specific agencies and required the agent’s permission to travel between them.

Indian tribes from other reservations, too, petitioned their agents for permission to come here hunting buffalo.

In the spring of 1883, a poignant letter appeared in the Bismarck Tribune, signed by 10 Mandan and Gros Ventre Chiefs living at Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota, telling of their deep longing to hunt the buffalo that had come “so near.”

“We want go out hunt buffaloes, is 60 miles from Ft. Berthold, which so near,” they wrote. ”We want go out so bad get some to eat and agent tells us we cannot go. He says if we go out guns and ponies, wagons be take away from us—this is what he tells us. . . We are working hard here.

“We have agent here, but he do not help us. He helps his folks—that’s all help we get from him. When he talk to us people here he talk like he was very kind to think of us Indians here. We often ask him to more eat and he tells us he is going to get plenty eat for us but we get tired waiting. Been three years. . . .

“He is trying to make people live half sick hungry. They got to get some to eat—they cannot.”

As far as is known this Ft. Berthold hunt was not permitted. Most certainly McLaughlin disapproved of allowing outside tribes to come onto the Sioux reservation to hunt buffalo. His letters make this clear.

During that last summer in 1883 there remained 10,000 buffalo in these final herds. They still ranged in this area—the northwestern corner of the reservation, said to be about half way between Bismarck and the Black Hills, between Hiddenwood Creek and the Moreau River. But their numbers dwindled swiftly toward fall.

“Just at this juncture,” reported Hornaday, “Sitting Bull and his whole band of nearly 1,000 braves arrived, and in two days’ time slaughtered the entire herd,”

Thus the Sitting Bull hunt that began around Oct 12, 1883, and slaughtered 1,200 buffalo was actually the very “last great hunt.” Sitting Bull and his band came from the Mobridge area about 60 to 70 miles nearly due east of here and apparently found that last herd about 10 or 15 miles to the south.

Hornaday quotes Vic Smith, a well-known hide hunter, “There was not a hoof left. That wound up the buffalo in the Far West, only a stray bull being seen here and there afterwards.”

(For more details see Ch 4, Scattered Survivors, page 56, in the companion book “Buffalo Heartbeats Across the Plains.”)

Grand River National Grassland

If you are wondering who owns this land, you need not look far. You and I own it, along with all other Americans!

This is what we call a Government Pasture, part of the Grand River and Cedar River National Grasslands administered by the U.S. Forest Service, USDA.

It’s officially under the multiple use concept that includes cattle grazing and public recreation.

This is a great place to hike and explore the rocky crests of hills and brushy draws and get closer to wildlife. Hiking here is especially exhilarating in early morning. Breathe in the fresh light air, smell the sage and wild prairie flowers, listen to the meadowlark and keep an eye out for mule deer.

Local ranchers lease these grasslands for cattle and through their Grand River Grazing Association care for the land, conserve soil, fence and improve grasslands and water sources.

If you don’t see cattle in this pasture, they are probably being rotated to another pasture. Regulations call for rotation between pastures every two or three weeks for best conservation of native grasses.

Site 4. Winter Hunt in the Slim Buttes

Find a scenic place where you might enjoy viewing buffalo in these pine hills—or joining the hunt, if you imagine you were riding with the Dupree hunting band and Thomas Riggs, missionary to the Lakota Sioux. Their hunting trip lasted months, so most any place you choose in and near the Buttes re-creates that hunt—they must have covered every draw and coulee.

Sites 4a and 4b denote the two passes through the Slim Buttes—to the northeast and south—where the Dupree hunting party spent 3 months in cold and deep snow in the pine hills. They prepared for 3 weeks and soon ran out of food—except for abundant buffalo meat. FM Berg.

Let your imagination wander. It’s wintertime with deep snow in the pines . . .

The winter winds blow cold, but excitement rides high among the 56 Lakota hunters riding with you. They just glimpsed their first buffalo in 15 years. Up ahead five or six big wooly stragglers plow through deep snow and vanished over the rocky slope above.

Two scouts, riding ahead and off to the side, hastily wave the hunters out of sight, motioning for them to swing wide and come on the buffalo against the wind.

Fearing their prey will escape while they circle, the men hurry their horses through heavy snow. All ride silently.

No one can see out of the ravine. Some lash their horses into a frenzy, using heel and quirt.

Rugged buttes and cutbanks punctuate the Slim Buttes landscape. Imagine riding horseback while pursuing buffalo through these broken lands—covered in two or three feet of blowing snow. Photo by Carole Rosencrans.

One impatient hunter grew angry at the delay. He glowered and signaled that the scouts were directing them too far around. He whipped up his horse to cut across the draw.

Suddenly a cloud of snow shot up. The man and his horse disappeared into a deep washout hole. He came up fighting to break free of the wildly plunging horse, legs and hooves kicking.

No one went to help him. After much effort he dragged his horse out and joined the hunters again, quietly cleaning snow from his gun.

“He’s cooled off now!” Roan Bear whispered loudly to Thomas Riggs, riding beside him.

As they jumped their horses out of the ravine, a small herd of buffalo snorted and stared at them, startled. In an instant they broke into a lumbering gallop, flinging up their stumpy tails as they ran.

Suddenly all vanished over a cutbank as if swallowed by the earth.

In a flash the riders charged after them—and dropped out of sight as quickly as did their game.

Swept along by a mad rush of hard-whipping riders, Riggs reached the edge of the bluff and—too late—saw the chaos below.

The Dupree hunters covered some rough country during their successful three-month hunt. Not always was it easy to pack the meat back to camp. Painting CM Russell, ACM.

At the bottom 20 horses were down, sprawled across a wide sheet of ice. Their riders scrambled to recover and hang onto their mounts.

Hunters race after the fleeing buffalo—their carcasses littered the white snow. Painting by Thomas Miles Richardson Jr 1848, AMC.

Across the creek, other horses raced after the fleeing buffalo. The lead hunters began to shoot. So did reckless hunters behind them, much to the disgust of those in the front. They turned and shouted angrily as bullets whizzed by their ears.

Buffalo fell. The black humps of their carcasses littered the white snow.

It was the day before Christmas, noted Thomas Riggs, the young missionary invited to join the Lakota hunters. The only white man on the hunt, Riggs—himself the son of a missionary to the Sioux—spoke their language and was eager to learn the Lakota customs and religious ceremony involved in hunting big game.

The hunters had gathered at the ranch of Fred and Mary Ann Dupris (also pronounced Dupree), on the Cheyenne River at the mouth of Cherry Creek, 35 miles west of the Missouri River.

A French-Canadian fur trader, Fred had built a log trading post and also ran a herd of 200 beef cattle. He and his wife Mary Ann, a Minnicoujou Lakota, raised eleven children and built an active community of their own. As each son and daughter married, they moved into a growing row of cabins built of cottonwood logs on a beautiful wooded flat.

Mary Ann offered to share their family tent with Riggs for the hunt, in which he joined Clearance Ward—his assistant at the mission, her son-in-law known in the tribe as Roan Bear—and many of her children and grandchildren. Fred, an older man in his 70s, opted to stay home by the warm fire.

After that first day’s hunt, the men most often went out in smaller groups following scattered herds of buffalo.

They made their way back to camp loaded with an abundance of meat and robes. Fires crackled and snapped, pots boiled and people ate well of the tasty buffalo meat. All were smiling and happy.

But it was hard work for everyone. The high, rough lands of the Slim Buttes were cut by deep washouts along canyons and dry creek beds. Deep, crusted snow and frequent blizzard conditions added to the difficulties. Snow fell almost continuously. The women worked with skill and efficiency to care for enormous amounts of meat and hides.

They set up their tents and tepees in a protected amphitheater on the southwest corner of the Slim Buttes where they turned the horses loose to graze. Two or three feet of snow covered the rich, cured grasses, but the savvy Indian horses pawed off the snow to eat their fill.

It was hardly a winter to spend in the rugged Slim Buttes living in tepees—where cold winds howl through the pine trees and snow settles deep in rocky canyons.

Nevertheless, the Cheyenne River Lakota stuck it out for three months, even though they had planned for only three weeks. They ran out of provisions and survived on little more than buffalo meat the last few weeks.

Riggs praised his horse Sam, an old hand at running buffalo, besides being very fast.

“Every man in camp knew him, for he was the horse that Canptaye had on the Little Big Horn against Custer in ’76. He was a professional and deserved the honor the Indians gave him.”

Riggs carried a sack of oats to feed his horses.

Plans were discussed and decisions made in the “soldier lodge” or council tent, the heart of the camp, a place of much smoking the pipe, religious ceremony and feasting. Later the crier announced their decisions throughout the camp. No women were allowed to enter the council tent, but they brought food and set it outside.

Two young men were selected as scouts, given detailed instructions and sworn into service. They made silent pledges, each with hands placed palm down flat on the earth.

At one point Riggs tells of an immense herd of buffalo arriving in the Slim Buttes from the southwest, stampeding into the night. This might have been part of the major migration coming in a direct line 150 miles from Miles City.

The Native hunters followed their game onto the grassy plains north of the Slim Buttes as well as deep in the Pine trees. Amon Carter Museum.

Riggs and five other hunters were returning to a temporary camp through deep snow, nearly exhausted, their pack horses loaded with meat.

In the darkness of that moonless night without stars, Cokan-tanka, a hunter who was a Sitting Bull lieutenant in the Custer battle, charged recklessly into the herd. His first shot missed and he suddenly found himself in the midst of a tight, galloping herd.

The buffalo ran against him on all sides, bumping against his legs. He shot again and missed again, using all the shells in the magazine. With great care he finally pulled a cartridge from the back of his belt and pushed it into the chamber.

While the mass of buffalo still pushed against him, he finally worked his way out of the running herd and shot his buffalo.

Another time, Roan Bear shot a buffalo that fell as if dead. He dropped off his horse to bleed it, but it suddenly leaped to its feet. He jumped back on his horse, which began bucking. The buffalo charged and finally the horse ran. Roan Bear turned, fired behind him and luckily, the buffalo dropped dead.

One night 40 men camped without food about 25 miles from the Slim Buttes. One hunter shot an old bull. They cooked the meat and ate the entire buffalo that evening.

They had only one large tent that barely held 32 men, so they made a partial tent from two pieces of canvas wagon sheet to cover the remaining eight men. It stretched no more than eight feet in diameter. In the partial tent, where Riggs slept, they roasted meat and boiled coffee in a three-quart pail.

All in all, despite the crowding, it was a pleasant evening, filled with much joking and laughter.

When finally the Slim Buttes winter hunt ended it was judged a success. No one was injured. The party killed around 2,000 buffalo. They took home more meat than the horses could pack and 500 prime buffalo hides.

Today the rugged Slim Buttes are a lovely place to hike, picnic and camp in the pine trees on a pleasant summer day. SDT.

Evenings the hunters sat around warm campfires in the tents, telling stories of the day’s hunt.

One night Riggs had a story of his own to tell. He had killed an enormous buffalo that afternoon, he said. After skinning it, he threw the green hide over his horse and sat on it. The hide instantly froze stiff as marble.

“In passing through a deep drift, I was lifted clear off my horse, which passed out from under me and left me straddling the frozen hide on top of nothing.”

His audience hooted with laughter. The amusing story of how he rode a frozen hide as a saddle with no horse under it was told over and over by his fellow hunters to hearty laughter, he wrote in his book “Sunset to Sunset.”

Riggs spent many evenings around the campfire talking about their experiences with the Dupree brothers and sisters. Likely they also talked of what they all knew was coming—the day when the buffalo herds would be gone forever.

Pete, one of the older brothers, became famous as one of a small handful of people who saved the buffalo from extinction.

It was his Lakota mother Mary Ann who suggested it, say descendants—and perhaps that happened right here. The Duprees ran a sizeable herd of beef cattle on the reservation. Surely some of those cows could be coaxed to raise a buffalo calf.

The idea took hold.

In early summer Pete Dupree—along with some of his brothers and probably sisters, too—set out for these buffalo ranges with a wagon. (See Site 5, Saving Five Calves)

They returned with five strong young buffalo calves—and helped change history. (For more information see Chapter 2, Winter Hunt in Slim Buttes, page 26, from the companion book “Buffalo Heartbeats across the Plains.”)

If you come to love the Slim Buttes—as local people do—and want to explore more of this long narrow formation of higher-altitude buttes, covered with pine trees and rocks, turn southeast and drive to the top of the South Pass.

Again we can imagine the Lakota hunting buffalo here in the pines and the mountainous pastures.

Buffalo are adapted to survive the worst blizzards of Northern Plains, from the natural insulation of their dense hair to their great strength and bulk.

The greatest challenges to range animals are the fierce storms of blowing and drifting snow. They often drift with the storm into water holes and other disasters.

Not buffalo. In winter, they face into the harsh blizzards that sometimes hit the northern plains, protected by their massive heads and shoulders. Their hair grows so dense that every square inch has 10 times as many hairs as an inch of cow hide, says Dale F. Lott, a University of California biologist.

With their forequarters well insulated by their heaviest hair growth, they move slowly into the wind until the storm blows over.

If snow lies deep on the prairie, buffalo plow down to eat grass. Their humps contain muscles supported by vertebrae that allow them to swing their massive, low-hanging heads side to side, sweeping away snow to reach plants and grass.

When water is frozen, they eat snow.

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog