Part2-Yellowstone Park in Winter

Buffalo travel through snow in wintertime in Yellowstone Park. Courtesy National Park Service.

Yellowstone National Park is a special place, and winter is a wonderful time to experience just how special it is. When winter snows descend on the park, many of the normal recreational opportunities are no longer available.

Visitors have unparalleled opportunities to observe wildlife in an intact ecosystem, explore geothermal areas that contain about half the world’s active geysers, and view geologic wonders like the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone River.

The seasonal change in winter provides new recreational opportunities to emerge: skiing, snowshoeing, snowmobiling and riding a snowcoach.

Not all roads are open to cars. However, you can drive into the park through the North Entrance at Mammoth year-round.

The winter season of services, tours, activities, and ranger programs typically spans from mid-December to mid-March.

At Mammoth, you can take self-guiding tours of Fort Yellowstone and the Mammoth Terraces, join a guided walk or tour, cross-country ski, snowshoe, skate, rent a hot tub, watch wildlife, attend ranger programs and visit the Albright Visitor Center.

Visitors in snowcoach on skis drives past bison feeding in deep snow in pine trees. Photo NPS, by Jim Peaco.

Visitors may legally soak in the Gardner River where hot thermal water mixes with cool river water. You can also arrange for over-snow tours to Norris Geyser Basin, Old Faithful and the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone River.

From Mammoth, you can drive past Blacktail Plateau, through Lamar Valley and on to Cooke City, Montana.

You may see bison, elk, wolves, coyotes, eagles and other wildlife along the way.

You can also stop to cross-country ski or snowshoe a number of trails along this road. The interior of the park is open to various over-snow vehicles.

Tours can be arranged through the park concessioner or operators at the various gates.

The interior of the park is open to various over-snow vehicles.

You can also stay at Old Faithful Snow Lodge, from which you can walk, snowshoe, or ski around the geyser basin, take shuttles to cross-country ski trails.

Winter Activities in Yellowstone

Or join a tour to other parts of the park such as West Thumb, Hayden Valley and the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone River.

Bighorn Ram makes his way through underbrush near Tower Junction. NPS.

Average winter highs are 20 to 30ºF (–6 to –1ºC). During warm spells, sunny days can be much higher, such as 60 degrees or more for several days.

Average lows are 0 to 9ºF (–17 to –13ºC). However, the record low—which struck in the midst of the depression on Feb 9, 1933—was 66° below 0 F (–54°C) at Riverside Ranger Station, near the West Entrance.

On this anniversary year Yellowstone Park will participate in the 15th Biennial Scientific Conference on the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem hosted by Montana State University, the Wyoming Governor’s Hospitality and Tourism Conference and the University of Wyoming’s Yellowstone National Park 150 Anniversary Symposium.

The park is also grateful to Wind River (Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho Tribes) and other Tribal Nations for planning a multi-tribal gathering on the Wind River Reservation later in the year.

Though fewer in winter, some Forest Rangers live in the Park year around and are always ready to answer visitor questions. About 4,000 employees work in Yellowstone Park each year. NPS.

This year Yellowstone will open 40 new employee housing units throughout the park along with groundbreakings on projects totaling more than $125 million funded through the Great American Outdoors Act.

These projects include two of the largest historic preservation projects in the country and a range of transportation projects that will address aging infrastructure.

This year will also mark the reopening of Tower Fall to Chittenden Road (near Dunraven Pass), a $28 million road improvement project completed over the past two years.

Wondering what to do on your visit to a snow-covered Yellowstone? The forest rangers of Yellowstone have plenty of ideas!

Take advantage of that white blanket of snow to zip through Yellowstone on a different form of transportation.

Winter in the park provides opportunities to take in the steaming geyser basins and wildlife via snowshoes, cross country skis, snowmobiles and snowcoaches.

The park sees between 2.8 and 3.1 million visitors annually, with most people visiting between June and August.

So if you can skirt those three summer months, or at least visit the less crowded areas at that time, you’ll find more relaxed, less congested roads and facilities.

Yellowstone is a big park with lots of room in the backcountry.

Buffalo feed in an area free of snow in Upper Geyser Basin in February 2015. Photo NPS, Sacha Charny.

Yellowstone Park annouonces that due to COVID-19, it does not currently have large events planned. However, this may change as the year progresses.

The Park advises prospective visitors to check the website: go.nps.gov/Yellowstone150 and follow #Yellowstone150 frequently in 2022 to stay current on commemoration information. (NPS / Jacob W. Frank, Jan 12, 2022; Contact: Morgan Warthin, (307) 344-2015)

Where to Stay in Winter

Many of Yellowstone’s hotels and cabins, including the famous Old Faithful Inn, are only open during the summer season. However, there are a couple of options for lodging during the winter inside the park.

Pending public health guidance: The Old Faithful Snow Lodge and Cabins, winter tours, and the Obsidian Dining Room, will be open from December 16, 2021, through March 6, 2022.

The Mammoth Hotel and Cabins, winter tours and the Mammoth Hotel Dining Room, will be open December 15, 2021 to March 7, 2022.

Buffalo follow each other keeping to narrow trail through deep snow as they brush it aside to feed on the grasses far below near Tower. NPS, JPeaco.

It is often easier to stay just outside the park, avoiding traffic and enjoying area accommodations such as on Hebgen Lake. There is also a premiere RV park in Yellowstone, just outside the West Entrance.

What to Wear in Winter at Yellowstone

Winter weather in Yellowstone can be severe, but when you’re dressed appropriately it’s fun to brave the cold.

One of the most important tips to attire in this environment: Wear layers—especially if you’re going to be moving around skiing, snowshoeing or hiking.

Your layering lineup should include a windproof, hooded outer layer and base layers, like wool or synthetic long underwear-esque items for both your upper and lower body.

Avoid cotton jeans and sweatshirts if you plan to be active; these items lack wicking ability leaving you wet and cold.

Choose thick socks and boots when hiking over well-trodden areas and add gaiters to the mix if you’ll be wandering through knee-deep snow.

Hats are a must since you lose most of your heat from your head, and don’t forget the gloves/mittens to keep those fingers warm.

Pro tip: Disposable hand-warmers stuffed into mittens can be a treat for those who get cold easily or have poor circulation to their hands.

One thing many people forget when adventuring outside in snowy conditions: sun protection. High-altitude sunlight reflecting off of snow is even more intense than at lower elevations, so be sure to pack the sunglasses and lather sunscreen onto any exposed skin to avoid sunburn.

Be Aware of Soundscapes

The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem has many sounds with important ecological functions for reproduction and survival. They form a soundscape.

Sounds in the quiet of winter may be heard at great distances—so listen, if only to the silence of winter.

Greater Yellowstone’s soundscape is the aggregate of all the sounds within the park, including those inaudible to the human ear.

Grizzly Bear protects a buffalo carcass in Yellowstone River as Bison walk single file through pine trees along shore above. NPS JPeaco .

Some sounds are critical for animals to locate a mate or food, or to avoid predators.

Other sounds, such as those produced by weather, water, and geothermal activity, may be a consequence rather than a driver of ecological processes.

Human-caused sounds can mask the natural soundscape. In and near developed areas human-caused sounds that mask the natural soundscape relied upon by wildlife and enjoyed by park visitors are, to some extent, unavoidable.

The National Park Service’s goal is to protect or restore natural soundscapes where possible and minimize human-caused sounds—while recognizing that they are generally more appropriate in and near developed areas.

The potential for frequent and pervasive high-decibel noise from over-snow vehicles has made the winter soundscape an issue of particular concern in Yellowstone.

Management of the park’s winter soundscape is important because over-snow vehicles are allowed on roads in much of the park.

The quality of Greater Yellowstone’s soundscape therefore depends on where and how often non-natural sounds are present as well as their levels.

Yellowstone’s Abundant Wildlife

Visitors have unparalleled opportunities within Yellowstone’s 2.2 million acres to explore geothermal areas that contain about half the world’s active geysers, view geologic wonders like the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone River and observe wildlife in an intact ecosystem.

Yellowstone National Park is not only a geologic wonder, but also home to abundant wildlife. As a wildlife preserve, visitors flock to this region to see animals in their native habitats.

In winter a close observer can expect to see a great many of these animals and birds:

- Bison/Buffalo, of course

Roaming wild throughout the park, Yellowstone is home to approximately 3,500 magnificent bison—a number that sometimes reaches 5,000 or 6,000 with a couple years’ calf crop. These massive animals are approximately 2,000 pounds and commonly frequent the Hayden and Lamar Valleys.

- Bald Eagles – Dotting the shores of Yellowstone’s rivers and lakes, bald eagles are commonly sighted as they look for their next fish-filled meal. Adult eagles are 30 to 45 inches in height.

Bald Eagle feeds on lake trout he speared with his beak in the shallows of Lewis Lake. NPS JPeaco.

- Bighorn sheep – Roaming the hills and mountains throughout Yellowstone, these sheep weigh 200 to 300 pounds, ranging in color from dark brown to light brown, have curved horns and a white behind.

- Black Bears – Common sightings are between March and November. Visitors need to remember to maintain space and to never approach wild animals, especially bears.

- Coyotes – Some of the largest coyotes in the U.S. live in the park, weighing 30 to 40 pounds. Smaller than wolves, coyotes live an average of six years.

- Elk – In the summertime with calves, Yellowstone is home to 25,000 elk. Elk weigh 500 to 700 pounds and are commonly sighted in the Mammoth region in meadows and large fields.

- Grey Wolves – Reintroduced to Yellowstone Park in 1995, this area is now home to more than 325 gray wolves. Lamar Valley is commonly frequented by wolves.

- Grizzly Bears – The best time for visitors to obtain a glimpse of a grizzly bear is between March and November. Grizzly bears are commonly sighted and rangers have information about areas that are safer for long-distance viewing.

- Moose – Second in Yellowstone to bison, moose weigh 1,000 pounds and are seven feet in height. The males’ feature telltale cupped antlers that make for outstanding photos.

- Mule Deer – These large deer can jump at a moment’s notice. Formerly known as blacktail deer, mule deer are distinguished by a black-tipped tail and oversized ears. Yellowstone is also home to white-tailed deer and pronghorn antelope.

- Trumpeter Swans – The world’s heaviest airborne bird, swans weigh 23 to 30 pounds and are distinguished by their white bodies and long, graceful necks.

- Badgers – Seldom seen, but common within the park, badgers often dig dens and live in holes, searching out their prey.

- Foxes – Distant and cautious, these animals can be spotted in Lamar Valley and on Specimen Ridge.

- Mountain Lions – Only 20 to 35 mountain lions inhabit the park. Weighing 100 to 160 pounds, mountain lions are a member of the cat family.

- Otters – Social and playful, otters are found along rivers and lakes, including Trout and Yellowstone Lakes.

- Small Mammals – Yellowstone is home to ground squirrels, chipmunks, red squirrels, marmots, northern flying squirrels, porcupines, beavers, muskrats, pocket gophers, voles and mice.

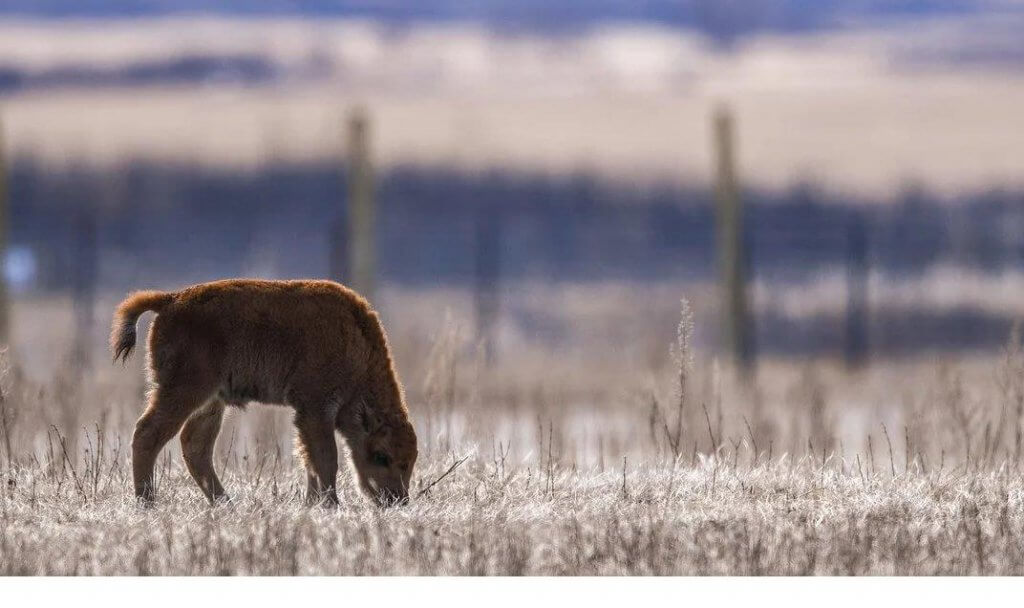

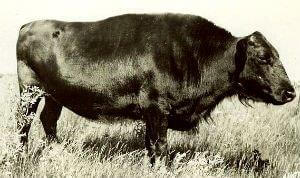

Buffalo in Winter

Buffalo are much more than America’s largest land mammal—they are culturally ingrained in our history and embody the strong and resilient characteristics of the American people.

Now our National Mammal.

While Bison are by no means the only active animals in winter in Yellowstone, we can almost guarantee you’ll see Buffalo anywhere along the roads where travelling is easier in deep snow.

Some of them hang out in the geothermal areas of Yellowstone. They especially seem to enjoy the warmth of the many geothermal areas. Buffalo like to get warmed up in winter too, just like we do.

Buffalo seem to enjoy the warmth of geothermal areas in winter. NPS.

Winter can sometimes be a challenge for bison, but these hardy animals are built to survive.

They might not be moving fast. In fact will likely be at least temporarily slowed down—with huge heads buried deeply in snow as they eat green grass.

Every year when mid-winter arrives, snow can blanket the northern Great Plains, temperatures can drop well below zero and the winds can howl unmercifully, and yet bison remain alive and well on the hostile landscape.

Indeed, the rangers tell us bison have evolved digestive, physiological, and behavioral strategies that allow them to survive some of the harshest weather in North America.

During the cold winter season, bison develop thick, woolly coats that help protect them from freezing temperatures and harsh winds.

It is said that a bison’s winter coat is so thick and provides insulation so effective that when snow accumulates on its coat, it will not melt from the heat of the bison’s skin.

Their skin also thickens in response to cold temperatures and fatty deposits appear to insulate the animal. This is important because during winter storms, bison will actually turn toward the storm, hunker down, and wait for it to pass.

With thick coats and creating a low profile, bison can survive the same storm that would kill many domestic livestock.

Bison also have the ability use their large head and massive neck and shoulder muscles as snow plows to forage in snow as deep as four feet!

But what is perhaps most impressive is how eating grass allows them to have enough energy to survive the winters.

Think about it: in winter, a big, hearty stew full of meat and potatoes sounds appetizing to many people. We crave those large, filling meals to keep us warm in the middle of winter.

Could you imagine eating only stalks of celery after skiing or working in zero degree weather all day?

Well that is almost exactly what bison do, and they have adapted to efficiently find nourishment from low quality forage that allows them to battle blizzards, minus 40 degree temperatures and 50 mile an hour winds.

Under cold stress, bison have developed the adaptation to minimize nutritional needs and slow their metabolism to conserve energy. Metabolism is a term used to describe the process by which our bodies convert food into energy.

People say bison during the winter are time minimizers rather than energy maximizers. In other words, bison cannot merely eat more food and more often to compensate for the low nutritional forage they eat.

Instead, they slow down their metabolism, the amount of time they spending foraging, and the amount of food they consume—in order to conserve energy. Bison also have the ability to generate internal body heat through digestion.

Bison slow down their metabolism in winter to conserve energy. They also have the ability of generae internal body head during digestion. Here feeding in deep snow on Swan Lake Flat. NPS, Neal Herbert.

Forage is retained longer in their gut—due to the increase of indigestible plant material found in the winter—which allows them to eat less but still receive the nutrition they require.

Without these adaptations, surviving the freezing temperatures and blizzard storms would not be possible.

Pregnant female bison lose a substantial amount of body mass over the winter. Pregnant bison will mobilize fat reserves during late gestation periods to meet increasing nutritional demands.

How Yellowstone Wildlife Adapts to Winter Chill

Forest rangers tell us how wildlife adapt to the sometimes harsh winters of Yellowstone.

Behavioral

- Red squirrels and beavers cache food before winter begins.

- Some birds roost with their heads tucked into their back feathers to conserve heat.

- Deer mice huddle together to stay warm.

- Bison, deer and elk sometimes follow each other through deep snow to save energy.

- Small mammals find insulation, protection from predators, and easier travel by living beneath the snow.

- Grouse roost overnight by burrowing into snow for insulation.

- Bison, elk, geese and other animals find food and warmth in hydrothermal areas.

Buffalo cross boardwalk ahead of visitors and find winter warmth at Fountain Paint Pots. JPeaco.

Morphological and Physical

- Mammals molt their fur in late spring to early summer. Incoming guard hairs are longer and protect the underfur. Additional underfur grows each fall and consists of short, thick, often wavy hairs designed to trap air. A sebaceous (oil) gland, adjacent to each hair canal, secretes oil to waterproof the fur. Mammals have muscular control of their fur, fluffing it up to trap air when they are cold and sleeking it down to remove air when they are warm.

- River otters’ fur has long guard hairs with interlocking spikes that protect the underfur, which is extremely wavy and dense to trap insulating air. Oil secreted from sebaceous glands prevents water from contacting the otters’ skin. After emerging from water, they replace air in their fur by rolling in the snow and shaking their wet fur.

- Snowshoe hares, white-tailed jackrabbits, long-tailed weasels, and short-tailed weasels turn white for winter. White provides camouflage but may have evolved primarily to keep these animals insulated as hollow white hairs contain air instead of pigment.

- Snowshoe hares have large feet to spread their weight over the snow; martens and lynx grow additional fur between their toes to give them effectively larger feet.

- Moose have special joints that allow them to swing their legs over snow rather than push through snow as elk do.

- Chickadees’ half-inch-thick layer of feathers keeps them up to 100 degrees warmer than the ambient temperature.

Biochemical and Physiological

- Mammals and waterfowl exhibit counter-current heat exchange in their limbs that enables them to stand in cold water: cold temperatures cause surface blood vessels to constrict, shunting blood into deeper veins that lie close to arteries. Cooled blood returning from extremities is warmed by arterial blood traveling towards the extremities, conserving heat.

- At night, chickadees’ body temperature drops from 108°F to 88°F (42–31°C), which lessens the sharp gradient between the temperature of their bodies and the external temperature. This leads to a 23% decrease in the amount of fat burned each night.

- Chorus frogs tolerate freezing by becoming severely diabetic in response to cold temperatures and the formation of ice within their bodies. The liver quickly converts glycogen to glucose, which enters the blood stream and serves as an antifreeze. Within eight hours, blood sugar rises 200-fold. When a frog’s internal ice content reaches 60–65%, the frog’s heart and breathing stop. Within one hour of thawing, the frog’s heart resumes beating.

Bison travel single file along road where snow recently has been plowed. NPS Jacob Frank.

Our Elk Hunt

On one memorable trip to Yellowstone Park—actually in the dead of winter—my sister Jeanie and I spent a week there. Just outside the park, hunting elk with our Dad one Christmas vacation when we were in high school.

We drove our stock truck the 340 miles or so from our ranch in eastern Montana to the north border of Yellowstone so we could take along our most-trusty saddle-horse Buck to drag out the elk.

We’d also have space to haul him and the elk carcasses we planned to bring home.

We lived that week in 1948 in a snug canvas tent pitched just outside the Park fence near a trickling creek not far from Gardiner.

First thing, Jeanie and I had to shovel the deep snow away, so it didn’t thaw under our tent. Then Dad carried in a wood-burning stove with a stovepipe to poke out the top.

On the Firing Line

From Dad’s hunting friends we’d heard a lot about the Famous Firing Line. Not really a place you want to be.

The Firing Line was a place where hunters spaced themselves before daylight between the Park fence and herds of elk which came out of the park to feed during the night.

When shooting started at daybreak the elk tried to run back into Yellowstone Park where they knew they’d be safe.

It was all too easy for hunters to get trapped between the fence, the rifles and frantic elk.

Every morning Jeanie and I ate breakfast hot cakes Dad made on our small stove—at the crack of dawn. Then we fixed a sack lunch for each of us and climbed the big mountain above us.

As we climbed we checked the prospects: How many elk came out of the park during the night before to eat in wooded side draws?

Bull Elk rests in snow near Blacktail Ponds. NPS Jacob Frank

Might they be still outside the Yellowstone Park fence, out of sight in the draws and legal to shoot?

It was 1948 and we learned to shush along through deep snow in long-tailed, old-fashioned snow shoes and carry our heavy 30.06 war surplus rifles (borrowed from hunting friends) into the deepest parts of the mountain and back.

It took all day and we were exhausted as we fell onto our bedrolls at dusk. A long story, but between the three of us we did shoot and bring home two big elk—and Buck, too.

We found out what the ‘Firing Line’ meant. Not a good thing, but a mind-bending adventure for sure!

April Snow Plowing

Bison grazes at dusk along creek in Hayden Valley. NPS.

Most of the park is now closed for a couple weeks in April to plow the roads in preparation for the summer season.

In 2022, road opening dates for the summer season have not been announced.

For reference, in 2020, the roads opened on these dates: April 17 (West Entrance), May 1 (East Entrance), May 8 (South Entrance) and May 22 (Tower Fall to Canyon and the Beartooth Highway to the Northeast Entrance). Road openings are pending weather conditions.

___________________________________________________________________________

NEXT:

___________________________________________________________________________

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog