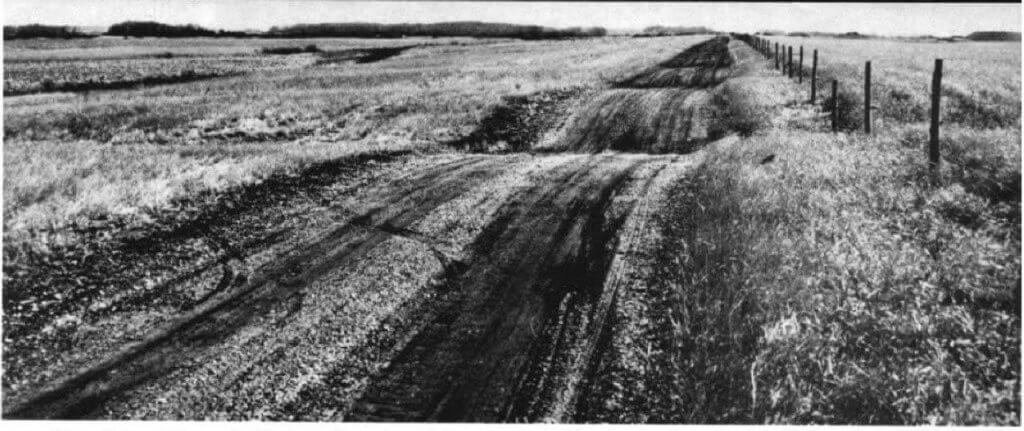

Several bison trails (dips in road) crossing at right angles a beach ridge of ancient Lake Agassiz in Pennington County, Minnesota, near the northeast edge of the mid-continent grassland and the northeast edge of the former bison range. Fence is along crest of beach ridge. Photo from Lee Clayton.

We know that thousands of buffalo roamed across the face of the Great Plains in ancient times.

Where we live, in the northern plains of western North Dakota, they’ve been hunted for at least the past 7000 years—and likely grazed here for many more thousands before humans arrived.

They migrated across hills and valleys, sometimes stampeding in great herds, running for miles, such as during the rumbling thunderstorms and crashing lightning that lit up the skies.

When they ran—and even when they plodded along in great herds, grazing as they went—over hills, ridges and valleys—when the ground was wet they made deep trails in soft ground.

Then they walked away, only to return in another season, often following the same old trails.

The trails grew deeper and wider. Sometimes buffalo trails dominated the terrain so powerfully they changed the course of waterways.

Now geologists—and ordinary people like you and me—are finding buffalo trails in many places across North Dakota and the rest of the plains and prairies.

How do they find them?

Early homesteaders noted them first and some correctly identified them as buffalo trails and passed that knowledge down to their descendants who still work the land.

So if you’d like to find out where buffalo trails are in your area, start by asking old-timers and listen to what they have to say.

Some local people—ranchers, pilots and people with an interest in history—already know where there are honest-to-goodness buffalo trails.

And there are probably many more just awaiting our discovery.

If you do find any, please pass that on to us! We’d love to be able to share some of these ancient buffalo trails with our community—perhaps our Dakota Buttes Visitors Council can add them to our tours!

Here are ‘best ways’ to find Buffalo Trails:

- In Spring when the grass is short (or winter days between times of snow cover)

- Throughout the plains and prairies in pasture lands which have not been plowed

- In soft and permeable soil (where rainfall soaks in readily—instead of draining off, which erodes slopes and destroys trails)

- The trails are like trenches, about 3 feet deep—but on steeper slopes may be 9 to 12ft deep. As wide as 6 to 60 ft across—typically 15 to 30 feet. Stretched out invarying lengths depending on soil and terrain—may be as much as ½ mile long

- In some areas trenches show up in combination with higher ridges of topsoil as if clumps of dirt have been kicked up and gobs of mud released after being stuck to hooves

- Where they cross depressions the trenches may be replaced by ridges

- Trails are usually straight or slightly curved

- They may run parallel to prevailing winds—such as on the diagonal from Northwest to Southeast

- May lead around bogs, to water or salty areas (?)

- The trenches tend to cross ridges, small hills and valleys

- They might be identified on hikes, from high points, low-flying airplanes or on Google maps

A North Dakota geologist who wrote about Bison Trails in North Dakota is John P. Bluemle. He was employed by the North Dakota Geological Survey from 1962 and served as ND State Geologist 14 years from 1990 until 2004.

Bluemle wrote the following report and says he adapted much of the content from an article by Lee Clayton: Bison trails and their Geologic Significance published in the national magazine Geology, Sep 1975.

John Bluemle worked with the North Dakota Geological Survey for 28 years from 1962, then spent 14 years as ND State Geologist, from 1990 to 2004.

Bison Trails in North Dakota: a Geological Survey

by John P. Bluemle

ND Geological Survey logo.

An unusual kind of landform found in several places in North Dakota was created by once huge herds of bison. The bison trampled shallow grooves across the prairie, forming trails that appear as lines on air photos.

These bison trails were first recognized in North Dakota in the 1960s by former University of North Dakota geologist, Lee Clayton.

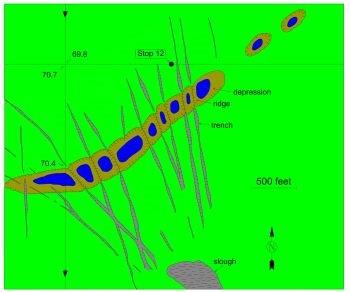

The trails are shallow grooves or trenches, generally a few feet deep, several feet wide, and several hundred feet long. Where they cross narrow depressions, the trails sometimes change to low ridges.

The ridges probably formed as sediment [solid fragmented material such as gravel transported and deposited by wind, water, or ice] tracked downslope by thousands of hooves.

Bison trails are common throughout the grasslands of the northern plains, and, in fact, many have been misinterpreted as bedrock joints [a brittle area of a large rock body with pressure-induced fractures with the same orientation] or glacial features such as a small washboard ridge that forms from material along the leading edge of a glacier.

Bison trails are straight or gently curved, and they show up on aerial photographs as dark lines. The trails tend to be parallel to high-relief features such as bluffs and steep slopes, and otherwise they typically trend northwest to southeast, parallel to the prevailing wind directions.

The trails were probably formed when large numbers of bison converged on water holes or were funneled along a particular path by the constraints of topography.

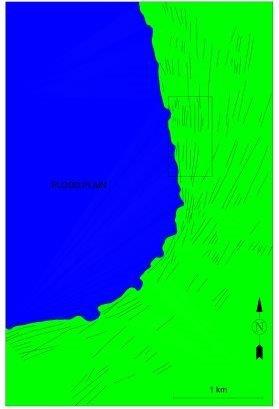

Bison Trails in the Denbigh Bog area in the old channel of the Souris River, about eight miles southeast of Denbigh in McHenry County. The arrow points to the bison trails along the eastern edge of the bog area. [Arrow is in upper ¼ th of photo, right of center.] The trails oriented mainly north-south, apparently a result of bison tending to walk around the edge of the bog. Bluemle.

The trails are best preserved where they cross areas of sandy soil, such as gravel deposits from glacial melt, perhaps because such soils are more permeable, allowing precipitation to infiltrate the soil rather than run off, eroding the slope and trails.

Even so, I have seen similar trails that cross areas of glacial till [till deposited mainly from glacial mudflows].

In areas of low relief, as in parts of the Red River Valley, the grooves or trenches tend to lie parallel to the prevailing wind directions, which throughout much of North Dakota was from the northwest (in winter) and southeast (in summer).

In areas of medium to high relief, the orientation of the grooves is controlled by the local topography. The grooves tend to cross medium-relief features such as ridges, small hills, and valleys. The grooves tend to be parallel to higher relief bluffs and steep slopes.

The features appear to be restricted to grassland areas of the interior of North America. They occur throughout North Dakota, to the forest edge in western Minnesota, in much of eastern Montana and Wyoming, in most of South Dakota, and in southern Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta.

Could these ‘Bison trails’ have an alternative geologic explanation?

For example, the trench-like features had earlier been interpreted as representing bedrock joints and faults. They have also been interpreted as glacial disintegration trenches, a kind of long, narrow depression resulting from the melting of an ice-cored crevasse filling.

The disintegration-trench hypothesis became untenable, however, when the trenches were found in southwestern North Dakota, beyond the limit of glaciation.

Furthermore, the ridged portion of the features consists of thick topsoil, not fluvial sand and gravel as would be required were they disintegration trenches. A bison-trail origin seems to best explain the features.

Bison trails changing from trenches to ridges where trails cross a shallow depression in a proglacial fluvial [sediments formed from glacial river runoff] plain in northwest corner, Kidder County. North Dakota. From Clayton and Freers, who mistakenly called them disintegration trenches. [a kind of long, narrow depression resulting from the melting of a glacial crevasse] Blue color—depression. Brown color—buffalo trail ridge.

Observation of cattle trails on steep slopes has suggested an explanation for the ridged portion of the features. Clumps of dirt are kicked along the trail by the walking cattle, and globs of mud stick to their hooves.

On a sloping trail, the clumps tend to be worked downhill. This results in transport of material down the path and produces a ridge at the base of the slope in continuity with the trench.

Did bison actually make the trails?

Many nineteenth-century travelers commented on the abundance of bison trails on the Great Plains. In 1846, Francis Parkman noted bison trails near the Platte River, as did General J. F. Rusling. According to Alexander Henry the Younger, bison trails were abundant in northeastern North Dakota.

Why should bison trails be restricted to highly permeable soil?

On slightly permeable soil, most of the precipitation runs off, eroding the hillslopes and destroying trails. On highly permeable soil, most of the precipitation infiltrates, resulting in only slight slope—wash erosion. For this reason, bison trails have been preserved mainly in areas of permeable, coarse soil.

Where were the bison going? Why do the trails tend to be oriented northwest-southeast, parallel to prevailing wind?

Perhaps they were watering trails [trails made by range cattle generally lead to water]. The bison may have located water by the downwind odor of water or vegetation growing next to the water.

Or, perhaps, the reaction of the bison to the wind itself, rather than the odor, was the cause. Perhaps seasonal migration routes controlled their direction.

Bison trails are of interest to geologists for two reasons: (1) they may be confused with geologic features, and (2) they may have influenced drainage patterns.

Bison trails can be distinguished from joints and faults in that ridges tend to represent trails where they cross depressions. Trails can be distinguished from normal stream-eroded gullies by the tendency of trails to cross over hills and through depressions.

Small stream valleys throughout much of the Great Plains are aligned parallel to the prevailing wind direction.

A possible reason is the initiation of gullies by wind or bison trails.

Small gullies are commonly initiated where runoff water [and wind erosion] has been concentrated in cattle trails, so it seems probable that a pattern of bison trails like that would result in gullies and small valleys oriented parallel to the prevailing wind.

Obviously, many trails in North Dakota have been enlarged by gullying. However, the magnitude of this influence is difficult to evaluate because bison trails are preserved mainly in areas of permeable soils where erosion has been slight.

In areas of less-permeable soils, where gullying has been extensive, all trace of bison trails has presumably been eroded away during the past century (since the demise of the bison).

(Report by John Buemle, with additional comments and explanation in brackets from Dr. John Joyce, Hettinger, ND.)

Happy hunting!

References:

Beaty, C. B., 1975, Coulee alignment and the wind in southern Alberta, Canada: Geological Society of American Bulletin, v. 86, p. 119 – 128.

Bluemle, J. P., 2000, The face of North Dakota, Third Edition: North Dakota Geological Survey Educational Series 26, 205 p.

Branch, E. D., 1962, The hunting of the buffalo: Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press, 240 p.

Clayton, Lee, 1970a, Olfactory factors in landscape evolution: North Dakota Academy of Science Proceedings, v. 24, p. 4

Clayton, Lee, 1970b, Bison trails and their geologic significance: Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs, v. 2, p. 381.

Clayton, Lee, 1975, Bison trails and their geologic significance: Geology, p. 498 – 500.

Coues, Elliott, ed., 1965, The manuscript journals of Alexander Henry…: Minneapolis, Ross and Haines, 1027 p.

Mollard, J. D., 1957, Aerial mosaics reveal fracture patters on surface materials in southern Saskatchewan and Manitoba: Oil in Canada, August 5, p. 26 – 48.

Zakrzewska, Barbara, 1965, Valley grooves in northwestern Kansas: Great Plains Journal, v. 5, no. 1, p. 12-25.

NEXT: Part 2: Crossbreeding Buffalo with Cattle in Canada

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog