Are they Cattalo, Catalo, Hybrids or Beefalo?

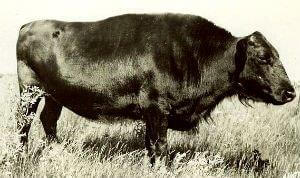

This catalo is likely from a cross between a Buffalo bull and polled Angus cow. The offspring are born with random markings and conformation, this one turned out extra hairy with dark cape-like covering and slim hind quarters.

Cattlemen of the old west who struggled with cold and blizzards looked at the mighty monarchs of the Plains with admiration and considerable envy.

“Wouldn’t it be great,” they said, “To raise beef animals with the hardiness and smarts of the buffalo, which could still produce the large beef cuts from the tenderloin and hips of fat beef cattle?”

Surely that would be the best of both worlds! It sounded good. And amazingly simple.

From the beginning many people have attempted to crossbreed the two species.

Today crossbreeding—as beefalo—is again experiencing a resurgence in the health food market.

During the bison population bottleneck, after the great slaughter of buffalo during the 1800s, the number of bison remaining alive in North America declined to as low as 800, according to David A. Dary in his (Ital) Buffalo Book, 1989.

A handful of ranchers gathered remnants of the existing herds to save the species from extinction. Some thought it would be important to breed a few bison with cattle in an effort to produce more cattle with the hardiness of bison. Accidental crossings were also known to occur when buffalo cows ran with beef cattle.

Two early crossbreeders were Buffalo Jones of Kansas and Charlie Goodnight of the Texas Panhandle, both pioneer buffalo ranchers who rescued wild buffalo calves.

In northwestern Texas, Charles Goodnight ran big herds of cattle, 148 buffalo and 35 cattalo, the latter being a cross between the wild buffalo and the domestic polled [without horns] Angus cattle. The cross—when a rare calf was born, did not have horns.

In summing up his cattalo efforts Goodnight said: “I have been able to produce in the breed the extra rib of the buffalo, making 14 on each side, while ordinary cattle have only 13 ribs on each side. They make a larger and hardier animal, require less feed, and longer lived, and will cut a greater percent of net meat than any breed of cattle.

“No one knows how long a buffalo will live. I have had a buffalo cow more than 28 years old which produced a calf. The cattaloes are a decided success. They will carry their young and make beef at any season of the year.

“The buffalo, and the cattalo as well, never drifts with a storm, and knowing the road home goes there in the face of the worst blizzard.

“The buffalo has better manners than the domestic animal. For example, does not muddy the water of a pool or stream when it drinks, stepping up to the edge of the water only, and never stepping in.

“I believe it will only be a matter of time until they will be used on all the western ranges.”

However, he added, “Buffalo and domestic cattle will not mix in the same herd or be at all neighborly unless grown up together from calfhood.”

Buffalo Jones’ Grandiose Claims

Buffalo Jones was even more enthusiastic than Goodnight.

In his book Buffalo Jones 40 years of Adventure, published in 1899, Jones wrote in glowing terms of his beloved crossbreds.

It all started, he said, while travelling through the plains after a terrible blizzard that fateful winter of 1886, when he saw thousands of dead cattle carcasses.

“When I reached the habitat of the buffalo, not one of their carcasses was visible, except those which had been slain by hunters. Every animal I came across was as nimble and wiry as a fox!” he wrote.

“I thought to myself, ‘Why not domesticate the buffalo which can endure such a blizzard, defying storms which would destroy cattle?’

“Why not infuse this hardy blood into our native cattle and have a perfect animal, one that will defy all these elements?

“Catalo are produced by crossing the male buffalo with the domestic cow. Yet the best and surest method is the reverse of this [domestic bull with buffalo cow].

“Only the first cross is difficult to secure. After that they are unlike the mule, for they are as fertile as either the cattle or buffalo. They breed readily with either strain of the parent race—the females especially.

“It is very difficult to secure a male catalo. I have never been able to raise but one half-breed bull and he was accidentally killed before becoming serviceable.

“The half-breeds are much larger than their progenitors of either side, the cows weighing from 1200 to 1500 pounds.

“Major Bedson of Manitoba, succeeded in raising a male half-breed, but unfortunately made a steer of him when young. At 5 years old he was butchered, and dressed 1280 pounds—equivalent to a live weight of 2480 pounds.

“The quarter and three-quarter buffalo are not so large as the half-blood. About the same size as ordinary good cattle.

“The fur of the three-quarter and seven-eighths buffalo makes the finest robes. This fur is perfectly compact and when bred from the black strain of cattle is as handsome as that of the black beaver.

“Some of the half-bloods are excellent milkers, yielding a fair quantity of milk, which is as rich as that of the Jersey. The nearer they approach the full-blood buffalo, the less quantity is produced, but the milk is correspondingly richer, as the milk of the full-blooded buffalo cow is richer than the Jersey’s.

Many cattle breed crosses were attempted over the years, including a Brahmalo—the offspring of a Brahman cow and a buffalo bull from Afton, Oklahoma. It was said to grow a buffalo coat in winter and sheds to a Brahman hide in summer.

“The catalo are quiet animals, so long as you keep hands off. They are good feeders, have excellent appetites and are invariably in excellent flesh, though fed on any kind of provender. I have successfully wintered them on the range without any artificial food or shelter, as far north as Lake Winnipeg. They withstood the cold when the mercury reached 50 degrees below zero, without artificial food or shelter.

“I have succeeded in crossing with almost all the different breeds of cattle, but the Galloway is unquestionably the safest, most satisfactory and produces the finest and best robes.

“The catalo inherit more of the traits of the buffalo than of the domestic cattle. They face the blizzards and when the first of the unwelcome storms appears in early winter, the domestic cow and her calf bid adieu to each other. The cow drifting with the storm—while the calf faces the blizzard and follows the buffalo herd.

“They all have solid colors—they are either black, seal brown, brindle or white. I never saw or heard of a spotted catalo. They are somewhat inclined to be cross, and when the cows have young calves at their sides are exceptionally so.

Cow might be brindle—or white face if from a Hereford mating. Hair was claimed by Buffalo Jones to be ‘as handsome as that of the black beaver.’

“After all my experiments in crossbreeding, I feel confident it can be made successful if the right class of cows is secured and they receive the proper treatment—without which none can hope for success.

“I did not only make a failure, but two or three of them. Yet by persistent efforts succeeded in a remarkable degree in producing the very kind of animal my imagination dwelt upon while in western Texas in 1886.”

Another claim—apparently quoting Jones himself—reported, “Buffalo Jones has made a thorough study of the habits of these animals, and by careful experiments in crossing with native cattle has produced a race which he calls the catalo, a magnificent creature.

“The head is less clumsy, the hump less prominent, and the hinder parts more symmetrical than in the buffalo.

Sometimes the head was less clumsy, the hump lower in a cross, but not always. This photo came from Elk Island in Canada.

“The catalo is far superior to the domestic animal for beef. Steaks cut from its dressed carcass are delicious, and it has been proved that 100 pounds more of porterhouse steak can be cut from the dressed catalo than from the ordinary steer.

Buffalo Jones developed a unique theory, which seemed reasonable to many. Ideal crosses would be to breed one fourth buffalo for southern ranges, one half for the great plains, and a hardier three-quarters buffalo to live in the far north.

Many Names: But do They Matter?

Jones also coined the label ‘Catalo’—spelled to give 3 letters of the alphabet to each species, he said. Others later changed it to ‘Cattalo,’ as being plainer for pronunciation. The Canadians generally called their crossbreeds ‘Hybrid.’

It is said the term Cattalo is defined in the U.S. as a cross of bison and cattle which have a bison appearance, while In Canada, cattalo was used for hybrids of all degrees and appearance.

Still later, a new generation created the name ‘Beefalo,’ and started several organizations—which eventually joined forces as the American Beefalo Association.

After nearly 150 years of crossbreeding this group now tells us, ‘The perfect balance has been found’ in 3/8th’s Bison and 5/8th’s domestic cattle. They apparently define a full Beefalo as one with 3/8ths (37.5%) bison genetics and animals with higher percentages of bison genetics as ‘bison hybrids.’

Beefalo brings a name change, but the same old claims are on display. Sure enough, this new cross allows ‘all the best qualities of both animals to be present.’ Can you beat that?

But who cares? It doesn’t matter, does it? Aren’t all these terms created for the purpose of appearing fresh, new and viable?

“It is claimed that the crossed breed combines the docility of the domestic animal with the endurance and the large size of the bison, and that the half-breeds grow to maturity in less time than domestic cattle.

“The flesh, also, is said to be very palatable, and the fur, while retaining all the good qualities of that of the bison, is much softer and finer.”

Less Glowing Reports

The Logansport Reporter, Indiana, back on Jan. 14 1898, had issued a warning, “One of the alleged successful experiments is located on a cattle farm a few miles south of Durrant Wis., where, it is said, three bison captured a few years ago have, by cross-breeding, increased to a herd of 43 animals; and the owners of the herd believe that an extension of their method of cross-breeding will bring them a fortune in the near future.

“The statement, however, has not been received with much favor by cattle dealers, who are aware of the ill success of several similar experiments during recent years.”

Perhaps Buffalo Jones’s catalo existed mostly in his dreams, charges Larry Barsness in his 1995 book (ital) Heads, Hides and Horns.

He reports that Jones in 1887 turned two-year-old immature buffalo bulls in with his Galloway cows, hoping for a hybrid calf crop—no calves resulted. The next year he reported 80 or 90 pregnant cows—but only produced 2 calves.

“Worse, 30 of the cows had died giving birth or before. But he cruelly kept on experimenting. He believed larger domestic cows would survive birth more successfully. When they continued to die he went on breeding.”

Barsness charges that most of Jones’ so-called catalo were purchased to save time in breeding and he actually bred catalo for only six years or so. Then he went broke and had to sell his hybrid herd five years after he’d bought it.

“Hardly time enough to allow him to become the catalo expert newspaper and magazine stories made him out to be. Jones didn’t deserve his reputation as a catalo breeder; his bad luck cut off his breeding experiments.”

Jones had run up against major difficulties. “First, too many domestic cows die; no cattlemen can stay in business losing a third of his calf-bearers each season. Second, surviving cows often abort bull calves or bear them dead. Third, any live bull calf often proves sterile.”

Barsness says others experienced these same losses of pregnant cows. Charles Allard gave up trying to raise cattalo on Flathead Lake, Montana, because he lost too many cows. Rutherford Stuyvesant gave up when 19 of his Galloway cows died calving. PE McKilip in Kansas quit after 10 years for the same reason.

The cross of a buffalo cow with a domestic bull (versus a buffalo bull and a domestic cow) kills fewer cows but the bulls were generally afraid of the hairy cows and kept away unless raised together with them from birth, he says.

No one knew then why the large death losses. Promoters likely tried to excuse or ignore it.

So is Fraud Involved?

While many ranchers still hope for a cross that works, a scent of fraud pervades.

The Logansport Reporter, Indiana, in 1898 published a story that noted: One of the most successful buffalo breeders was that of the late Austin Corbin, the local banker and railroad magnate.

“Austin Corbin, son of the original owner of the herd, when asked for his opinion as to the probability of successful crossbreeding of the buffalo with domestic cattle, said:

“It may be possible, but guided by a knowledge of experiments made by my father. I would require very strong proof of the fact before believing that it has been, or can be done with success.

“At the suggestion of the Duke of Marlborough, my father, several years ago, imported a herd of [30] Polled-Angus cattle from Scotland, for the purpose of cross-breeding with the bison on our cattle farm at Newport, NH. The conditions were most favorable, as the bison were thoroughly acclimated and had largely increased in numbers, but the attempt at crossbreeding was almost a total failure.

“The result was so unsatisfactory that the experiment was abandoned.

“The only successful attempts at crossbreeding that I have heard of was that of Buffalo Jones, owner of an extensive cattle range in New Mexico. When he was here, some five years ago, Jones claimed that his experiment had been a success.

“But when I saw him last, six months ago. I judged from his unwillingness to discuss the crossbreeding of bison that his experiment had not continued to be successful.”

A female with large forequarters and hump at Wainwright experiment station in Canada.

Buffalo Jones went bankrupt and had to sell out. But he went down gallantly declaring—just a little more time and his crossbreds would have made him a fortune!

As Jones put it, “If I’d just had more time, this would be a Million dollar herd.”

‘Didn’t turn out very well’

Sometime after the first heyday of beefalo struck our community in the 1980s I was visiting with a friend who’s family had purchased beefalo semen from a relative.

His uncle was promoting it–I believe, as a way to get wealthy—in much the Buffalo Jones manner. (If he just had more time . . . as he went broke!)

When I asked my friend about their experience, he replied briefly that “It didn’t turn out very well.”

I didn’t press him for details. And he didn’t offer any. Obviously, his family hadn’t become rich.

Today there’s a resurgence of the Beefalo A.I. adventure, along with higher prices for buffalo beef and the special attraction of ‘organic health foods.’

It’s easy to artificially inseminate a few cows—or half the herd—without a thought for the possibility of dangerously incompatable fluids.

Consider this: Every state in the U.S. has several well-paid cattle experts and researchers. Most states also employ experts on horses, pigs, sheep and some even goats and poultry.

But in the US, does any state experiment station employ Bison researchers? I don’t think so.

This is not to say that bison ranchers are not hard-working men and women who make valuable contributions to the rural economy and to the conservation of bison. They are!

It is through the work of farmers, ranchers, conservationists and policy makers that buffalo have been brought from the brink of extinction to a healthy 400,000 head in North America today. Most of these bison are on commercial buffalo ranches.

Still, every Bison rancher is more or less on his or her own to find their own way. They learn from each other—and from the Bison organizations they belong to. Good for them, but it’s not enough!

Why haven’t disinterested researchers been giving the breeders facts? These producers are in business, and they need to know the research.

Recently there’s hope that more facts are on the way soon—with the new Center of Excellence on Bison developing at South Dakota State University. That science should be worth waiting for!!

Learning the facts about crossbreeding buffalo should also be interesting. I hope they’ll add that to the plan for research.

My observations on the dilemma of crossbreeding

The difficulty has always been that most of those who raise and market crossbred bison have a ‘dog in the race.’ And that’s been true since early times when this all started—at least 150 years ago. Fact is, promoters cannot be relied on to tell the whole truth, barnacles and all, which is needed.

But Buffalo ranchers and would-be crossbreeders deserve to know the truth from the start.

Up until now, U.S. research on buffalo has not involved disinterested agricultural researchers. Of course, marketers and promoters tend to be biased—we should expect that. Some certainly tell wild tales about their amazing beefalo and cattalo as did Buffalo Jones.

They find ways to ignore or excuse the infertile bulls, high death rates of mothers and calves, and the ungainly-shaped offspring they sometimes produce. Instead of the boasted ‘best of both species,’ offspring may be even more likely to harbor the worst of both.

But what about the Canadian researchers? They did a lot of weighing and testing through their 50 years of research. They must have found some answers.

___________________________________________________________________________

NEXT: Crossbreeding Buffalo in Canada-Part 2; Great Hopes for Northern Canada

__________________________________________________________________________________

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog