Part III. Viewing Sites 9 and 10—Fort Yates and Jamestown

Sitting Bull Visitor’ Center near Sitting Bull College in Fort Yates. Photo by LaDonna Allard.

If you’re a traveler coming into the Hettinger-Lemmon area from the east or west, you will likely plan to complete your tour by visiting Sites 9 and 10 either before or after the main section of your tour.

Otherwise, separate trips might take you through Fort Yates and Jamestown—which are somewhat to the northeast.

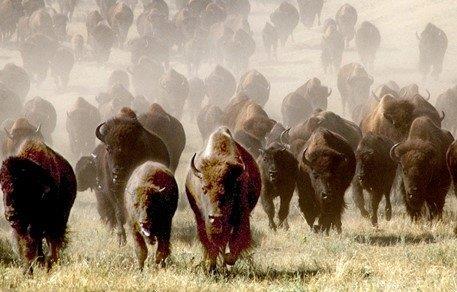

Tribal herds can be viewed at Ft. Yates, and other reservations. The “largest buffalo,” and a National Buffalo Museum that includes a full-body mount of the famed White Cloud reside in Jamestown.

If time allows, a stop in Bismarck at the North Dakota Heritage Center—midway between the two final sites—adds one more important theme to the buffalo story. Here you’ll find exhibits of the pre-historic bones of ancient buffalo found in the state.

Outdoor Events on Capital Grounds in Bismarck feature arts, crafts, food vendors and entertainment. Courtesy ND Tourism.

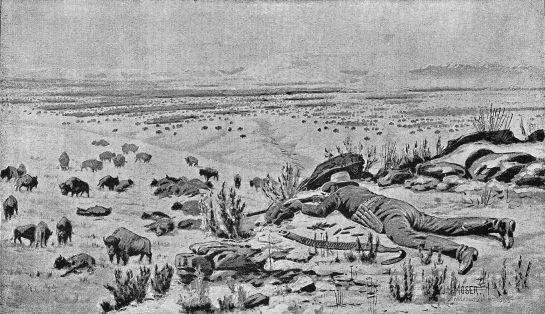

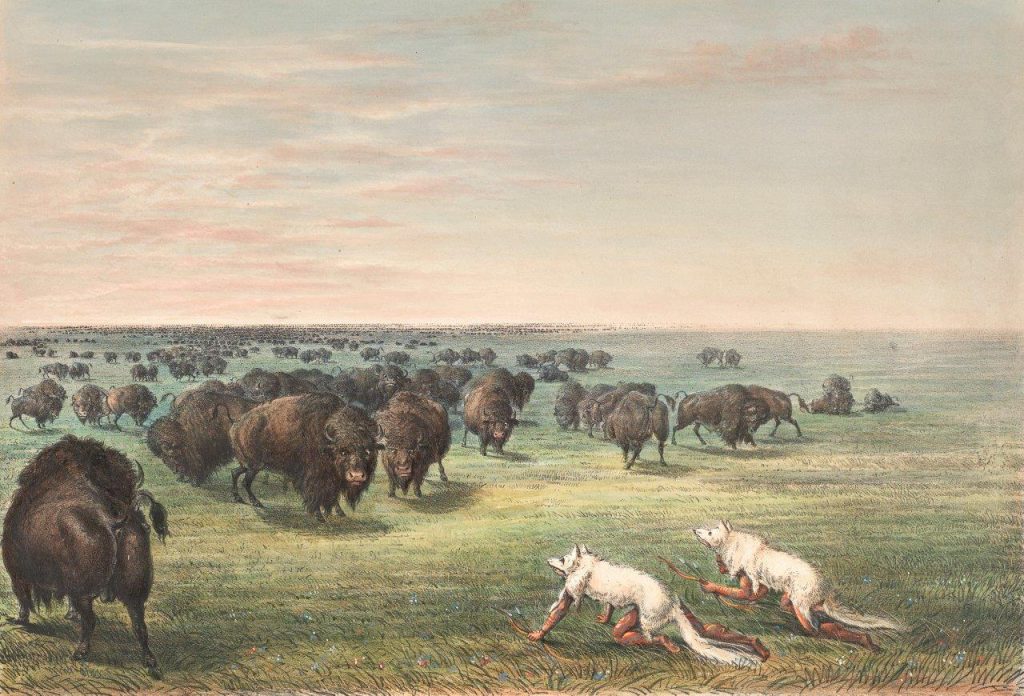

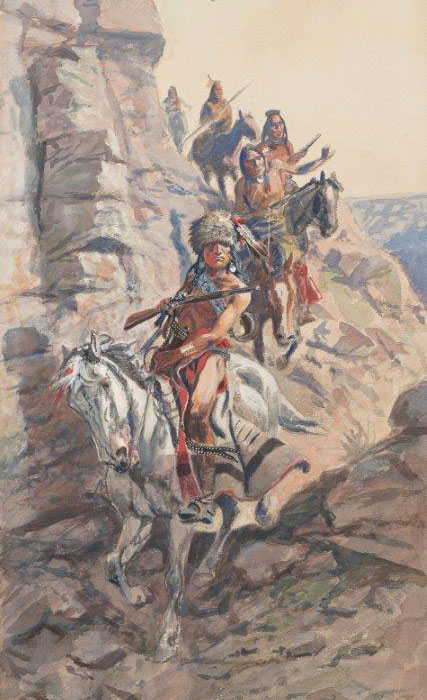

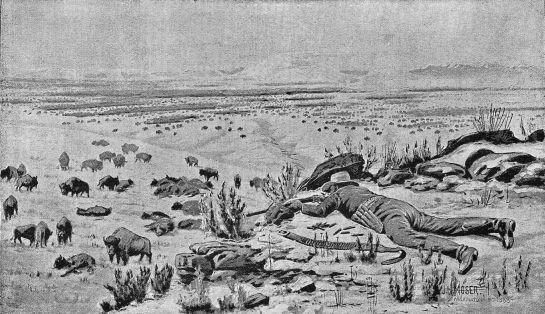

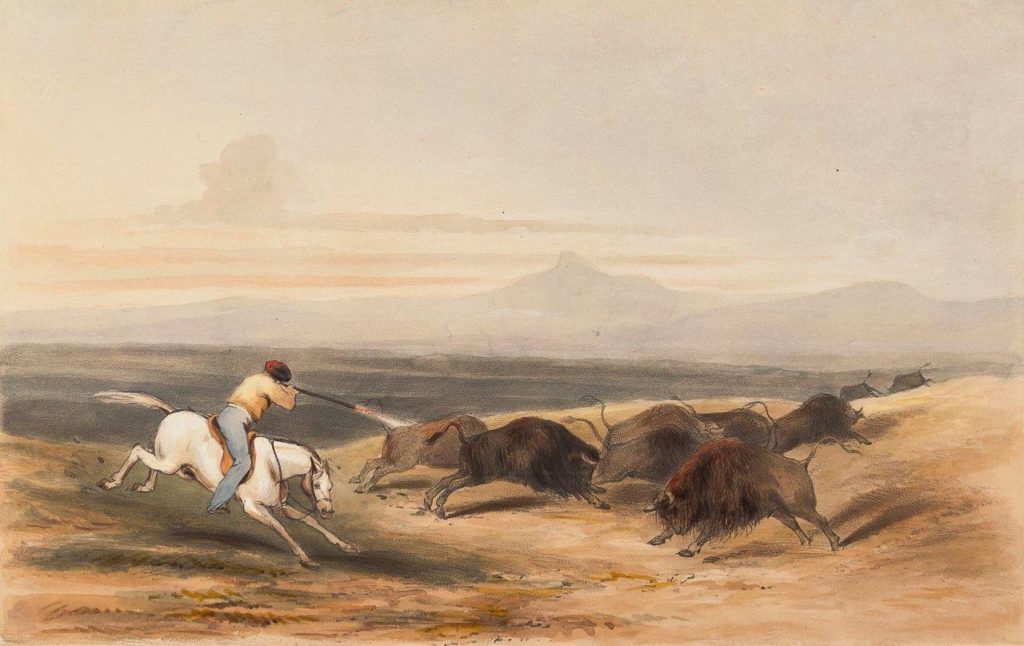

Part I. Sites 1-4 of this Tour, published in our Sept. 8, 2020 Blog, told of the great traditional hunts from 1880 to 1883. These last great buffalo hunts—the Hiddenwood Hunt, the winter hunt in the Slim Buttes and the valley of the last stand, which was the final harvest of the last 1,200 wild buffalo by Sitting Bull and his band on October 12 and 13, 1883.

This region, bordered by the North Dakota towns of Hettinger, Reeder and Scranton, and the South Dakota towns of Lemmon, Bison and Buffalo, is where Native people conducted the last traditional hunts of the majestic wild buffalo that once roamed here in huge herds on what was then the Great Sioux Reservation.

Part II. Sites 5-8, Sept. 22, 2020. Then, just before the last wild herds disappeared forever, the Duprees—a Native American family— returned to the hunt site (Site 5) to save 5 orphaned buffalo calves—and became internationally famous for growing their own buffalo herd at a critical time.

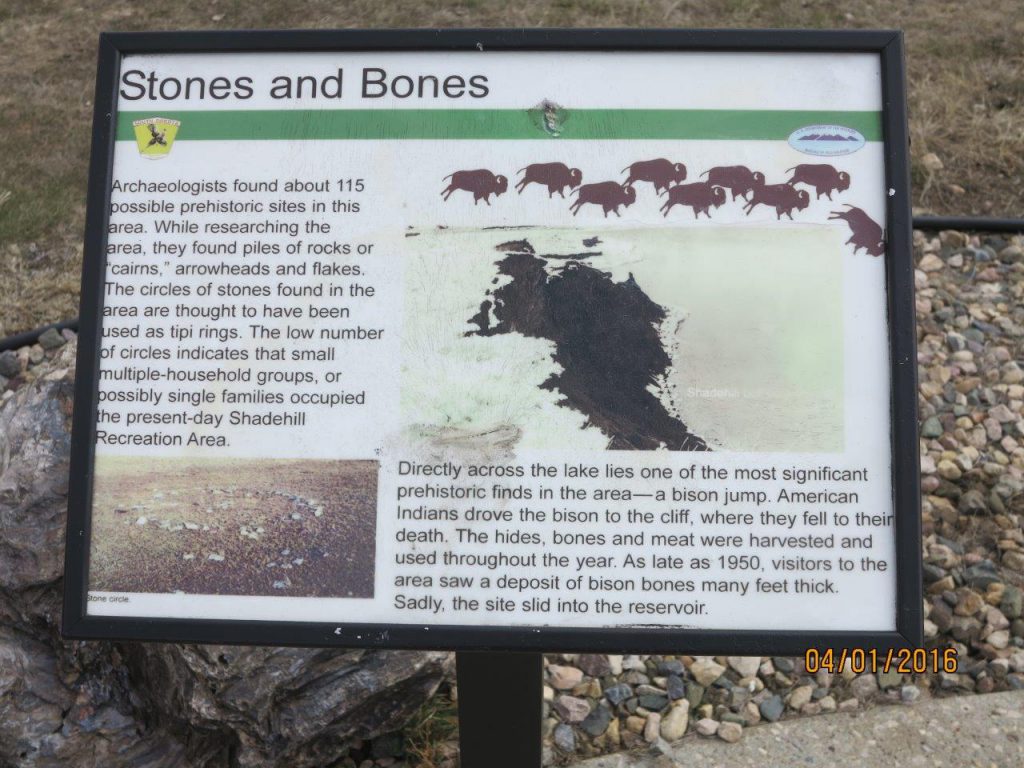

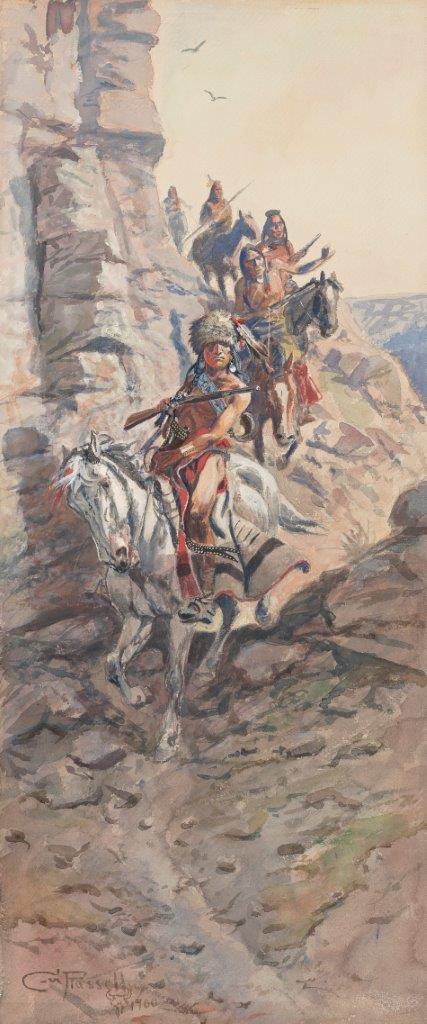

Included on this part of the tour are some ancient locations—such as the authentic buffalo jump at Shadehill SD, used for thousands of years before horses arrived on the Plains—and Native American traditions that incorporated buffalo into their culture.

This is the region where all parts of the Buffalo story come together.

There’s no other place like it for buffalo history and traditions—from ancient times until now, when nearly every tribe in the Plains owns their own buffalo herd and are delighted to share it with you.

So if you’re a traveler smitten by the iconic American buffalo, you can plan your next trip around buffalo sites you find here and on our website.

We outline world class trips to visit these buffalo-related sites, both historic and modern day.

North Dakota Tourism has added our Buffalo Trails Tour to its Best Places and promotes it with international tours. South Dakota Travel provides links as well. (This information is available in our Self-Tour Guide book “Buffalo Trails in the Dakota Buttes” available at local businesses and hettingernd.com/buffalotrails.)

Site 9. Tribal Herds—Standing Rock Sioux Reservation

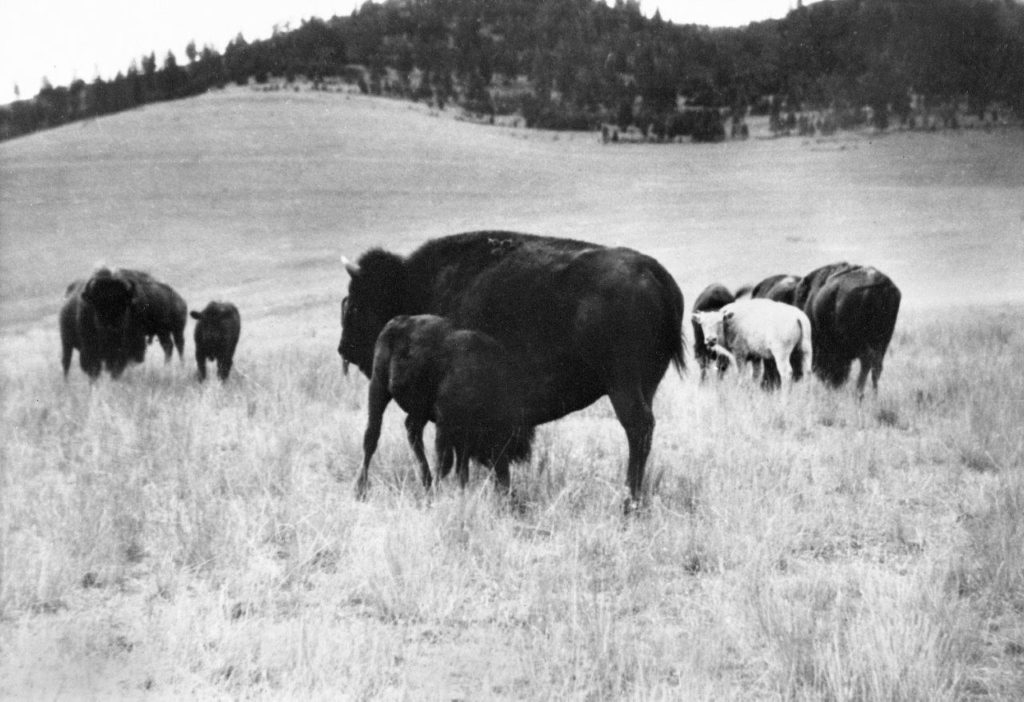

Buffalo in Standing Rock’s North Pasture graze in green grass by Highway 1806 (ND 24), just south of the Prairie Knights Casino. FM Berg.

Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, which spans the North and South Dakota border, headquartered in Fort Yates, N.D., has a long history of raising buffalo. Initially they were private herds, such as those owned by the Dupree family from the early 1880s.

The first permanent tribally-owned herd arrived in 1955—one bull and four cows—a gift from Theodore Roosevelt National Park, according to Mike Faith, Standing Rock Tribal Chairman, who was the Tribal buffalo manager for nearly 20 years.

Other buffalo came as donations from Wind Cave and Badlands National Parks in South Dakota, or were purchased with tribal funds and grants through the years. To improve genetic diversity, the tribe bought bulls from the Custer State Park buffalo sale.

Standing Rock now runs 400 to 500 buffalo in two herds—about the right size for the grazing land available. It’s important not to overgraze in the drought-prone plains, explains Faith.

To view one or both tribal herds owned by Standing Rock Sioux Tribe inquire at the tourism office in Fort Yates—it’s a beautiful building halfway up the hillside to the left as you approach the town of Ft. Yates.

Gift shop in Sitting Bull Visitor’s Center offers beaded moccasins, jewlery and other handmade crafts. Photo by LaDonna Allard.

You may need special permission and probably a guide to take you through the necessary gates and fences if you visit the south herd in the picturesque Porcupine Breaks or Hills. There the scenery is amazingly rugged and the roads primitive.

Buffalo graze through prairie dog town in the Porcupine Breaks pasture. Courtesy Standing Rock.

Or you may drive directly to the north pasture, which borders Hwy 1806 (ND 24) on the road to Mandan, just south of the Prairie Knights Casino (also owned by the SRS Tribe), and view the north buffalo herd through the fence.

Here the terrain is more rolling, carpeted thickly with green grass, less dramatic than the rugged Porcupine Breaks pasture up on the flat, but it also runs through some badlands country as it drops down toward the Missouri River on the east side.

As happens, off and on through an ordinary week, a knot of people gathers by the highway, watching buffalo in the north pasture through the double-high woven wire fence.

Smiling, murmuring softly—they might be a school tour from nearby Bullhead, Eagle Butte or Wakpala. Or tourists from Minnesota or Norway spilling from a charter bus.

Or perhaps a visiting group of Native people in traditional dress are performing a buffalo ceremonial. They’ve parked briefly along the highway or on the side road along the south edge of the pasture going east.

“We’d like a highway drive-off, so people can stop more easily,” notes my guide, LaDonna Brave Bull Allard, Historian and Director of Tourism for the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe.

After spending as much time as you like contemplating live buffalo, continue driving north to Interstate-94 at Mandan, where you turn east to Jamestown to view more one-of-a-kind buffalo-related sites.

InterTribal Council efforts—A homecoming

ITBC logo

Throughout Indian country buffalo have staged a homecoming.

Assisting and inspiring this come-back has been the mission of the InterTribal Buffalo Council for two and a half decades.

In February 1991, a meeting in the Black Hills of South Dakota, hosted by the Native American Fish and Wildlife Society, brought together 19 tribes to talk about the challenges they face with their own herds and how they can help other tribes restore buffalo to Indian lands.

Coming from all four directions, they discussed their tribes’ desire to obtain or expand buffalo herds and grow them into successful, self-sufficient programs.

Above and beyond the practical economics of it, they wanted to raise buffalo in a way that is compatible with their spiritual and cultural beliefs and practices.

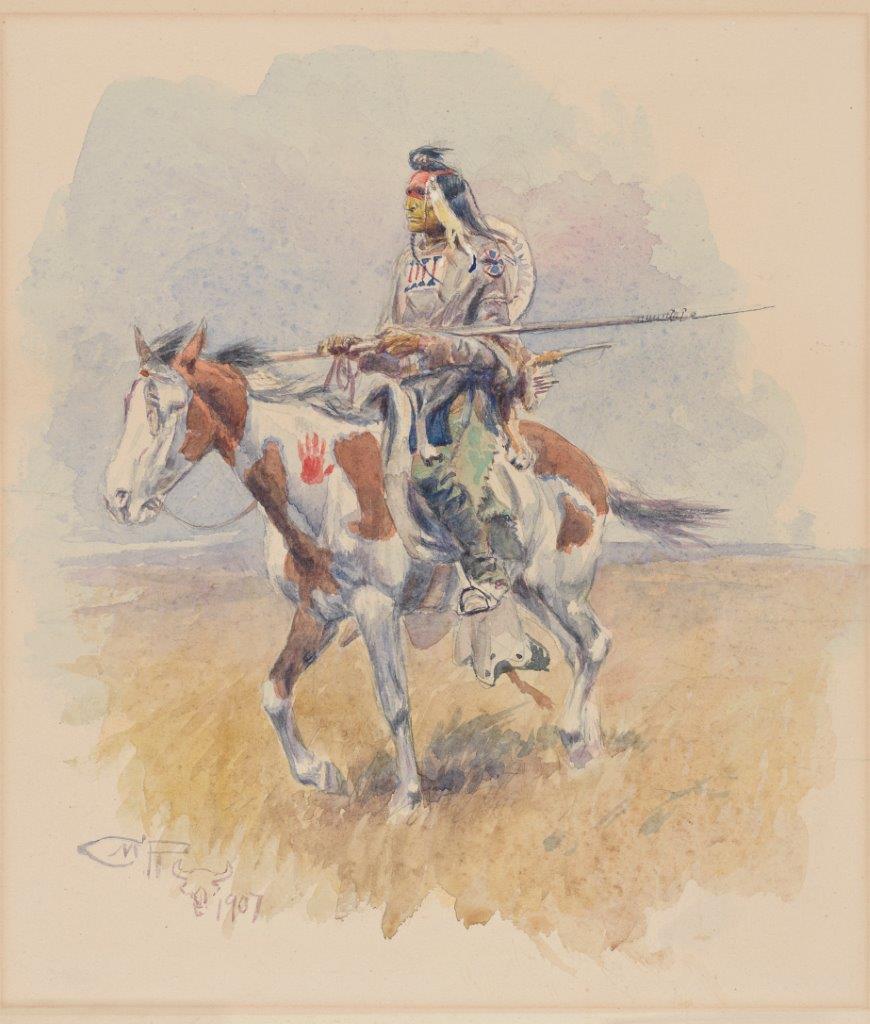

Buffalo represent the Native spirit and remind them of how their lives were once lived, free and in harmony with nature.

Together these Native leaders launched the InterTribal Buffalo Council, believing that reintroduction of buffalo to tribal lands will help heal the spirit of both the Indian people and the buffalo.

In June of that same year Congress voted to provide funding for tribal programs and to donate surplus buffalo from national parks and public refuges to interested tribes.

The InterTribal Council agreed to supervise grants and distribution of the animals.

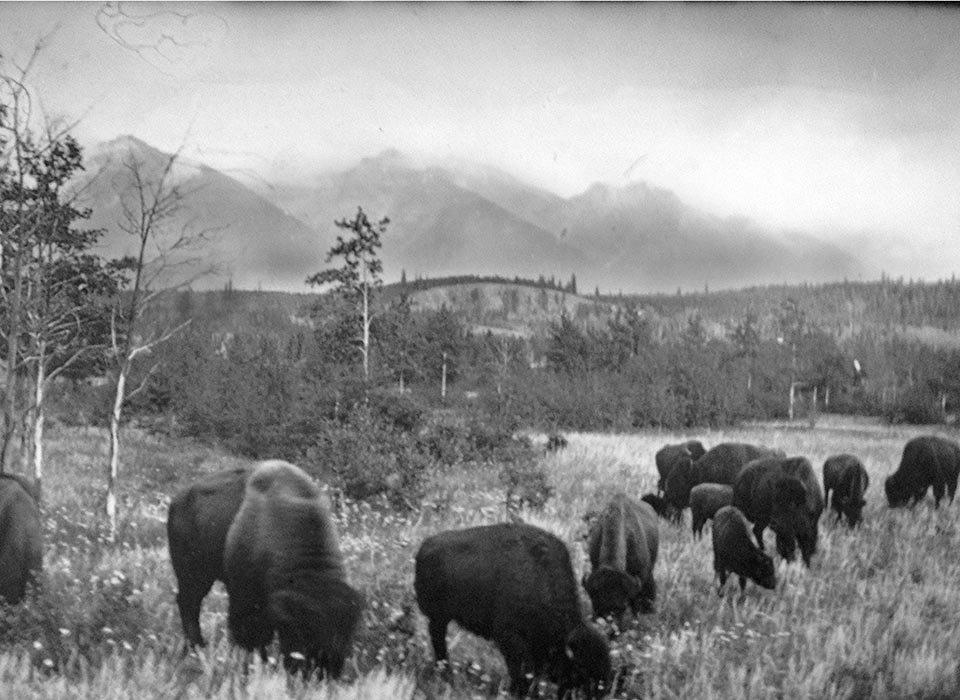

Buffalo began coming home to reservations in earnest.

Today 69 Indian tribes belong to the InterTribal Council, owning a total of more than 20,000 buffalo now living in tribal herds across the United States.

Many tribes run large buffalo herds for commercial as well as cultural purposes. Traditionally they believe restoration of buffalo to tribal lands will help heal the spirit of both the Indian people and the buffalo. Photo by InterTribal Buffalo Council.

Many are plains tribes with a long history of depending on buffalo for food, shelter and clothing. Others have no known history of hunting buffalo, but want the cultural experience for their people.

Mike Faith, as vice-chairman of the InterTribal Council, has worked with many of these tribes. He says some own large buffalo herds for commercial as well as cultural purposes.

Others set goals for a small herd mostly for cultural and educational purposes. They might slaughter only one or two buffalo a year for special celebrations and ceremonial use.

It depends on land available, land uses on the reservation, tribal population and historic dependence on buffalo.

InterTribal Council technicians explain working buffalo in the chutes at a workshop. Photo by ITBC.

“Quality over quantity is what counts,” explains Faith. “Whether they want a small herd—20 or 30, or a larger commercial herd—we can give help and technical assistance.”

No matter the numbers, Faith suggests it is important that new tribes take their buffalo venture seriously, hiring a competent manager.

The InterTribal Council offers training and educational programs—such as in low stress buffalo handling—and coordinates transfer of buffalo.

If desired, experienced leaders are available to help the new buffalo owners work out management and marketing plans that fit with their particular concerns and goals.

Sometimes the experienced buffalo handlers recommend fewer animal numbers to better accommodate the land available. A buffalo herd needs plenty of space, grass and water.

Details like building high, strong fences before the buffalo arrive are essential—and costly. There may be grants available to help, they suggest. They also work with federal agencies to help bring fractured lands together for pastures.

“Having the buffalo back helps rejuvenate the culture,” says Jim Stone, Executive Secretary of the InterTribal Buffalo Council based in Rapid City and a Yankton Lakota, “In my tribe, like others, the buffalo was honored through ceremony and songs. There were buffalo hunts and prayers to give thanks to the buffalo.”

The Council has adopted a lofty mission: “Restoring buffalo to Indian Country, to preserve our historical, cultural and traditional and spiritual relationship for future generations.”

Daily the leaders are reminded that buffalo represent the spirit of Native people and how their lives were once lived, free and in harmony with nature.

They believe that to reestablish healthy buffalo populations on Tribal lands is to reestablish hope for Indian people. And returning the buffalo to tribal lands will “help heal the land, the animal, and the spirit of the Indian people.”

“We have many cultural connections to the buffalo,” points out Alvah Quinn, a South Dakota Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate, the tribe’s Fish and Wildlife Director, who also has managed the local Extension Program.

“I grew up hearing about the buffalo, but we didn’t have any around on the reservation.” His tribe’s last recorded buffalo hunt was in 1879.

Quinn says he will always remember the rainy night in September 1992 when he helped bring the first 40 buffalo to his home reservation.

“I was really surprised that night. There were 60 tribal members waiting in the cold and rain to welcome the buffalo back home. After a 112-year absence!”

They now own 350 buffalo—one of many success stories.

In Alaska, Randy Mayo, first chief of the Stevens Village tribal council, believes being around buffalo can help people work through personal problems.

He acknowledges that when the village voted to move forward with raising buffalo, he didn’t know much about the animal that had provided food, clothing and shelter to his ancestors.

He learned a lot.

“Every time I come here it lifts me up,” said Mayo. “Just observing them, you never get tired of it.”

Herdsmen play a special role. Caring for buffalo enhances feelings of self-worth and pride in the men and women who work with them, reports Art Schmidt, South Dakota’s Flandreau Santee Sioux buffalo herd manager.

He sees an amazing change in the attitudes of people he hires.

A fenced viewing stand overlooking the Oneida Tribal herd provides a safe place for visiting groups. Courtesy Oneida Tribe.

“Knowing they are taking care of that beautiful magnificent creature—it becomes part of who they are and gives them a sense of pride in their culture,” Schmidt says. “They’re not just going out and doing their job and collecting a paycheck and going home.”

The Standing Rock tribe harvests 15 to 25 young bulls a year for its own use. Processed in Mobridge under federal inspection, the meat is donated to food distribution programs and provides buffalo roasts and stew meat for various celebrations.

Faith hopes to get buffalo meat into their school system of 800 students.

In many tribes, anyone putting on a community feed can request buffalo meat. It is served at graduations, funerals, naming ceremonies and community celebrations, and has become an honored part of the healthy foods in diabetes programs.

Cherishing Buffalo Meat

The opportunity to eat buffalo meat is cherished by Native Americans.

“Eat the meat of the buffalo,” say Native elders. “It’s healing. It keeps our people strong. It fills the soul as well as the body.”

Considered delicious and healthy, hearty and sweet, tasty and tender, buffalo beef is low in fat and cholesterol and high in protein, highly absorbable iron and zinc, plus other minerals and vitamins.

When grass fed, it has even less fat and is thus more nutrient-dense.

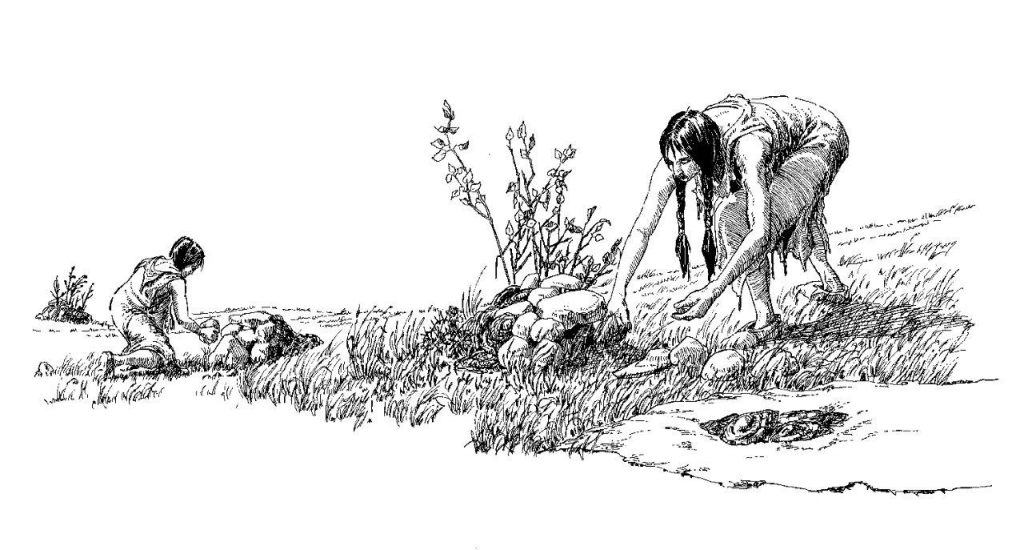

Butchering and caring for the meat is regarded as an integral part of the circle of life, and as an important skill to teach children.

“Every part has a meaning. We use them all,” Allard explains.

Some, such as the Fort Peck tribes in northeastern Montana, where I visited, have built their own butchering facility, out near the corrals, for tribal members who want to purchase and slaughter their own buffalo from the business herd of about 200 head.

Robert Magnan, Fort Peck Fish and Game Director, told me, “We have all the equipment and they bring their own wrap. We teach them how to cut up and cook the different parts.”

But first, says Magnan, “We talk to the buffalo. Tell them we need meat to feed our families. Thank them for their willingness to take care of us.”

Some tribes sell federally inspected buffalo meat and some sell buffalo hunts to people from across the United States and other countries.

Learning from the Buffalo

People can learn much from the buffalo, says LaDonna Allard.

“Our tribe is the original ‘Buffalo Nation—Pte Oyate.’ Everything we do is related to the buffalo. In our ceremonies we use all parts of the buffalo. In the powwow we dance like the buffalo. How we raise our children. . . “

Allard tells the story of a Native woman who neglected her children. The tribal judge placed them in a foster home and sentenced her to go each day for six months to watch the buffalo herd, writing down what she saw.

In six months she returned to court.

“What did you learn?” asked the judge.

“I learned that buffalo mothers protect and praise, and constantly care for their children. They teach—and discipline them too, but in a good way.”

“Do you think you can do that?”

“Yes. I want my children back. I’ll try to be a better mother—like buffalo mothers.”

The Council leaders recognize that even after more than a century of recovery, many Native Americans still feel an acute sense of loss over the destruction of the wild buffalo herds and all that represents in their lives.

The InterTribal Buffalo Council is committed to establishing buffalo herds on Indian lands in a way that promotes spiritual revitalization, ecological restoration and economic development. They suggest that for people who may be hurting, contemplating their own tribal buffalo can help them heal and bring a sense of wholeness and peace.

Teaching young people about traditional relationships and spiritual connections to the buffalo is important to Lisa Colome, a grasslands expert with the InterTribal Council.

“Native kids have a natural connection to the buffalo,” she tells me, her dark eyes warming. “They’re just naturally born with this awe. They are never disrespectful and show genuine caring. This is what tribes are seeking.”

She enjoys bringing children to see the buffalo.

“Once I brought a group of sixth graders. They watched silently as the buffalo ran over the hill out of sight. I said, ‘Just wait, I think they’ll come back if we’re quiet.’

“We peeked over the hill. The buffalo circled back and came within 25 feet. The kids had never been that close before.”

It’s easy to see that Colome is excited about her work, whether her day focuses on herd and forage health, or cultural and spiritual ties.

Not always do tribal herds bring financial benefits, she knows—often quite the opposite. But always she sees cultural value.

“I love being a part of developing tactics, plans and solutions that ensure buffalo are here for generations to come,” she says.

“Return of the buffalo awakens the Native spirit—it gives us hope of better lives.”

Site 10. National Buffalo Museum in Jamestown

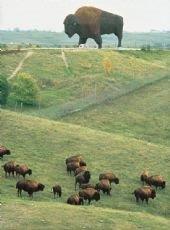

Jamestown ND—with its “World’s Largest Buffalo” overlooking the town and the buffalo pasture—may have been an obvious choice for locating the National Buffalo Museum. ND Tourism.

In the early 1990s the National Buffalo Association and the American Bison Association merged into the National Bison Association. They pooled their collections of buffalo-related artifacts, artwork, and historical memorabilia and looked for a historically significant place to display them.

Jamestown, ND, was perhaps an obvious choice.

Already it was home to the World’s Largest Buffalo, Dakota Thunder, built in 1959 on a hill above the town of Jamestown, right next to the Interstate—I-94. A frontier town had sprung up at its base, and a pasture between was planned for a buffalo herd.

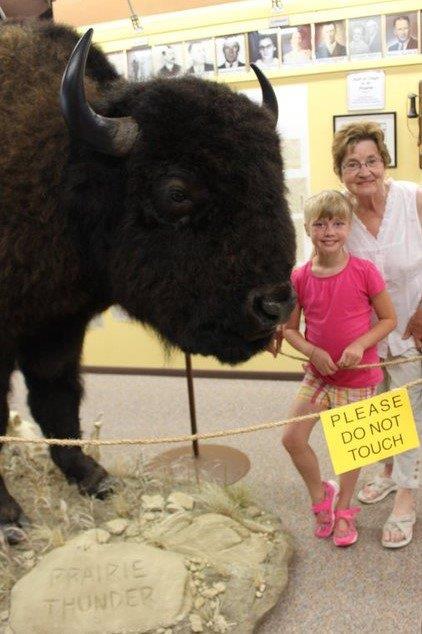

“Largest Buffalo” is a popular photo op for families. ND Tourism.

Further, the location had an ancient history of buffalo migrations along the south-flowing James River. A place where Native hunters lay in wait for easy hunting in fall and spring.

The new museum opened in June 1993, with the North Dakota Buffalo Foundation dedicated to its management and financial stability.

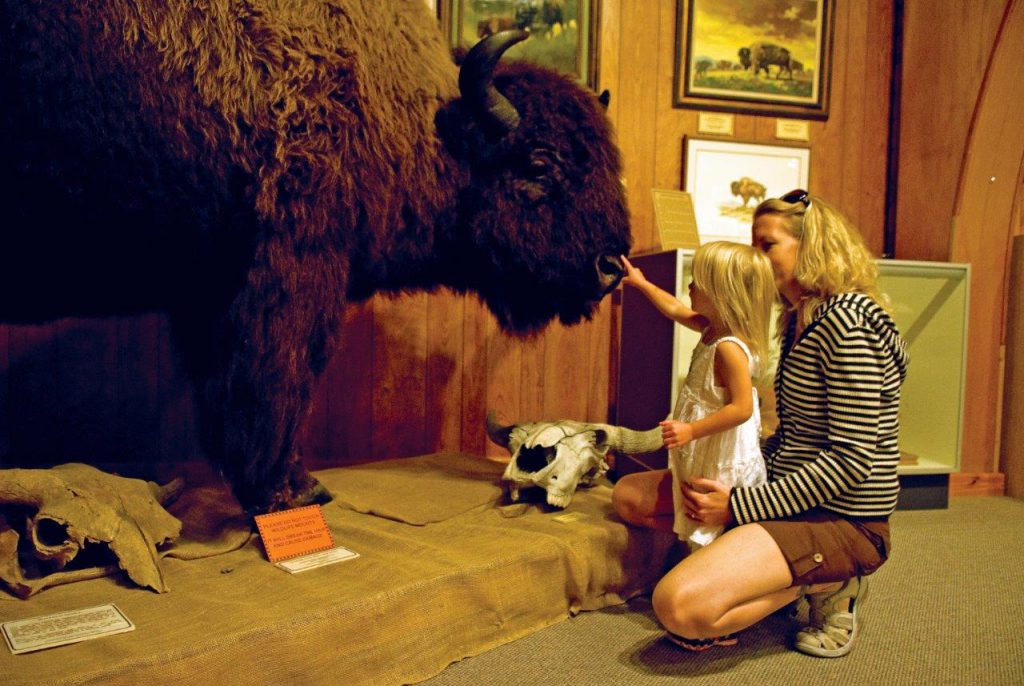

The museum is now home to numerous art works, artifacts, and related Native American items. Visitors see items such as a 10,000 year old bison skull, a complete skeleton of bison antiqus (ancestor to the modern bison), artworks and artifacts relevant to the history of the American bison.

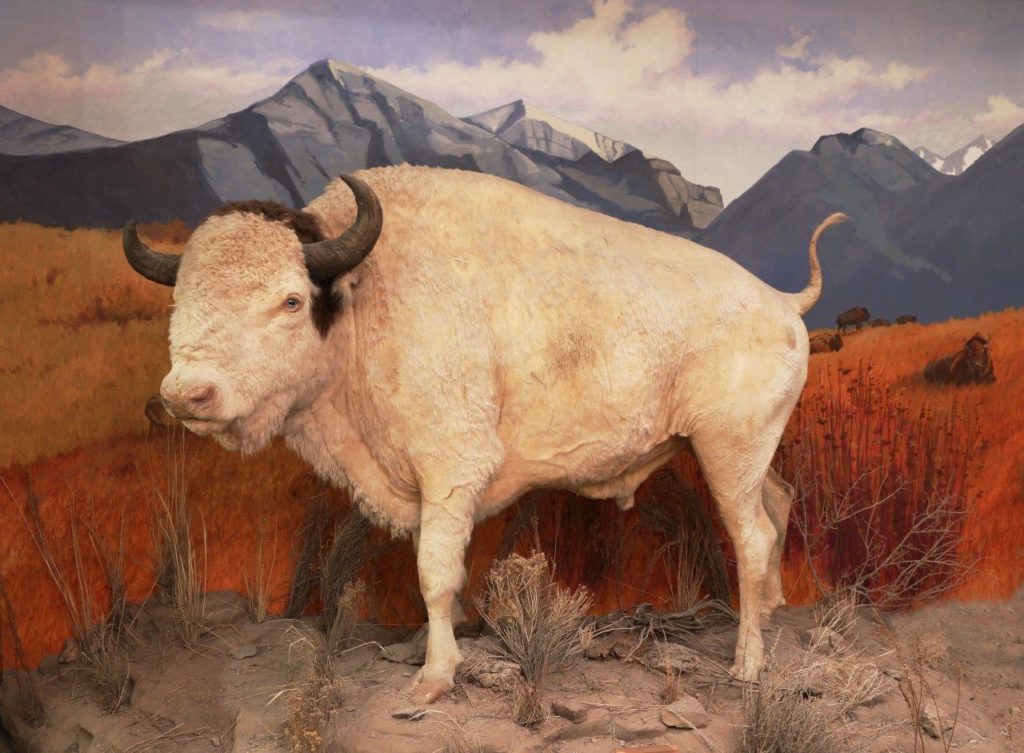

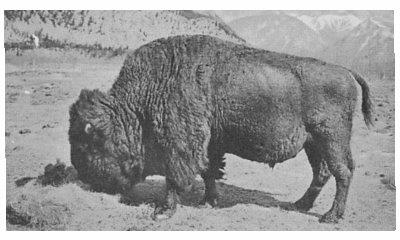

Featured in one room is the full body mount of White Cloud, Jamestown’s beloved albino bison, honored in a glass case and brushed to an elegant sheen. For 20 years she reigned as a prize of the local buffalo herd.

The Museum also hosts the Buffalo Hall of Fame, where visitors learn about the people who have had significant impacts on conservation and restoration of the US National Mammal. And of course an extensive gift shop.

Interactive exhibits are attractions of the National Buffalo Museum, as well as extensive buffalo art, gifts and buffalo cookies. ND Tourism.

Summer hours: Memorial Day to Labor Day, 8 am–8 pm daily. Winter hours: Mon-Sat. 10 am-5 pm. Admission $8-$6. (701-252-8648; 1-800-807-1511) www.buffalomuseum.com

World’s Largest Buffalo

Located at the end of Louis L’Amour Lane, stands the World’s Largest Buffalo Monument, rising tall on the hill in Jamestown, ND.

Buffalo pasture extends into green draws between the big buffalo and I-94. ND Tourism.

Drive through the gate at Frontier Village—it’s open with museum hours.

You will see the World’s Largest Buffalo Monument towering ahead. It stands 26 feet tall, weighs 60-ton—a fun photo op for your family.

A popular roadside attraction for over 50 years, the huge sculpture was created by sculptor Elmer Petersen. On the site with the National Buffalo Museum and a live herd of Buffalo, and an extensive Frontier Village.

Legendary White Buffalo: White Cloud Dynasty

Many plains tribes regard a white buffalo as sacred. Since 1996 traditional Native people have journeyed to Jamestown, North Dakota, to honor and see for themselves the dynasty of White Cloud and her offspring.

Dakota Legend, born to a brown mother in 2008, was believed to be grandson of White Cloud (adults in the Jamestown herd were not identifiable by ear tags or tatoos).

For about 20 years—from the time White Cloud joined the buffalo herd from the Michigan, North Dakota ranch where she was born until her death in Nov. 2016—her white hide showed up clearly among the brown buffalo herd.

Because of her rarity and easy visibility at the home of the National Buffalo Museum and the World’s Largest Buffalo, we added this stop to our tour.

When travelling east on I-94, we hope you will stop and see this miracle for yourselves—a heritage that may stem from the famous Big Medicine himself.

If you don’t see the buffalo herd or they are partially hidden from view, drive around the pasture or inquire at the Museum. You may be able to watch them from the museum’s viewing deck with the binoculars provided.

Or come to view them at different times of the day—buffalo like to keep moving.

Once in a great while, rare as it is, a ghostly little newcomer is born into a buffalo herd. A form of albinism, this can occur in any living thing, animal or plant.

From ancient times Native Americans have honored white buffalo and white robes as sacred and carried out special ceremonies to celebrate them.

Many Native people today continue these traditions.

In modern times, Jamestown, North Dakota, has been one of the easiest places to see authentic rare white buffalo.

In a narrow hilly pasture along the Interstate, tourists have spotted two and, at one time, even three white animals of purest beauty—grazing there in a herd of about 30 brown buffalo.

These were White Cloud, Dakota Miracle and Dakota Legend.

White Cloud, who was born in 1996 and died of old age in 2016, was a true certified albino with pink eyes and skin and not quite black horns. She is mounted and on display at the National Buffalo Museum where she lived most of her 20 years.

This dynasty of white buffalo began when White Cloud was born on a private North Dakota buffalo ranch not far away. The owners offered to share their joy and excitement with admirers through a special lease agreement, but preferred to remain anonymous.

Indian elders came with their drums and sage to welcome her. It was a fitting location for White Cloud and her white offspring.

Years ago Jamestown leaders erected the ‘World’s Largest Buffalo,’ a huge cement buffalo on the hill above town. Twenty-six feet high, it honors the great herds that once grazed these rich grasslands and followed a major migration route north and south along the James River valley—a route known for centuries to Native hunters.

Eventually, a historic Frontier Town sprang up beside the big monument, a buffalo herd found pasture, and the National Bison Association decided to locate its National Buffalo Museum there.

Depending on the season and pasture rotations, visitors were able to view one or more white buffalo at this site.

After first giving birth to three brown calves, in 2007 White Cloud produced Dakota Miracle, a white male. Then in 2008, Dakota Legend was born to a brown mother, believed to one of White Cloud’s daughters, in the same Jamestown herd.

Both these two white offspring had blue or brown eyes and dark horns and hooves.

Dakota Miracle grew to adulthood and outlived his mother by a few years, but unfortunately had some health issues. One evening he fell down a steep bank and, apparently unable to rise, was found dead the next morning.

Famous White Buffalo

Two other well-known white buffalo are Blizzard, a white bull that the Winnipeg Assiniboine Zoo purchased as a yearling in 2005 from “a U.S. herd,” to honor the buffalo as Manitoba’s Provincial emblem, according to zoo curator, Dr. Robert E. Wrigley; and Custer, a bull purchased as a seven-year-old from a North Dakota ranch in June 2014 by the Briarwood Safari Ranch, owned by Ron and Deborah Nease, in Bybee, Tennessee.

Famous white buffalo now deceased include what was probably the most famous Buffalo ever: Montana’s Big Medicine, born in 1933 who lived for 26 years on the National Bison Range. (See “Legacy of White Buffalo—Big Medicine,” featured in our Aug 25, 2020, Blog.)

Miracle was born in Wisconsin in 1994, and died at age ten. And, all too briefly little Lightning Medicine Cloud, born in 2011 in Texas, lived for only one year. This little white calf was owned by Arby Little Soldier, of the Lakota Sioux tribe from South Dakota.

Celebrating the Birth of a White Calf

Wherever white buffalo appear, Native people come to visit them, bringing gifts of tobacco ties, colored scarves, dream-catchers and other treasures. Elders perform ceremonials and blessings, waving smudges of sweet grass and singing prayers to drum beats for this highly spiritual animal.

Many plains tribes celebrate the birth of a white calf as a holy event, and regard the little calf as a sign of peace and harmony—and good times to come.

They affirm that the white buffalo symbolizes spiritual renewal and the hope of bringing people of all backgrounds closer together. Some see the white buffalo as a manifestation of the White Buffalo Calf Maiden, long revered in Plains tribes as a prophet.

The welcoming ceremonies were experiences he will never forget, reports Dr. Wrigley, of the Winnipeg Zoo. “I felt like I was stepping back into an ancient time to observe the most-sacred and private of ceremonies of a people little known to my culture.”

It has been, he says, “A wonderful experience interacting with numerous individuals from First Nations and Métis communities, and they have taught me so much about their traditional relationships with Nature and the spiritual world.”

Thank you for Joining us on our Northern Plains Buffalo Tour

Thank you for joining us on the Dakota Buttes Buffalo Tour of the Northern Great Plains—in the Hettinger/ Lemmon/ Bison / Buffalo area and the Grand River National Grasslands buffalo-related sites. Both historic and contemporary.

We hope you enjoyed it as much as we have in bringing it to you. This is a work in progress, so please share with us your comments and suggestions.

Through the months ahead we will be bringing you more tour-worthy buffalo sites throughout the US and Canada.

In the Dakotas you may also see buffalo at close range, driving among them within their ranges in Theodore Roosevelt National Park, both north and south units, especially near Medora, N.D. (check the prairie dog towns toward evening) and in Custer State Park in the Black Hills of S.D., as well as in tribal herds of every Indian Reservation.

So if you have any favorites, we’d love to hear about them. Thanks again!

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog