Part 1: Returning Wild Buffalo to Banff National Park

One of its first ventures was the display buffalo herd placed in a small 300-acre paddock near Banff in 1885.

Canada’s oldest national park—Banff National Park—is near the mountain resort of Banff and Lake Louise.

Moraine Lake in Banff National Park. Above the tree line—at about 2,300 m (7,500 ft)—the rugged mountains here are primarily rocks and ice. Rivers cut through deep canyons. Photo courtesy of Brandon Jean.

The scenery is spectacular, with rugged mountains rising on every side. The tree line is at about 2,134 m (7,000 ft), and above this is mostly rocks and ice.

Unlike other western mountain towns that focused on mining or agriculture, Banff was built as a tourist destination from the beginning. Planners for the Canadian Pacific Railroad built across Canada in 1885, discovered hot springs there and pronounced it tourist-worthy. The original Chalet Lake Louise was built on the lake shore in 1890.

At the time there were no roads. Only the transcontinental railway, towering Canadian Rockies, glaciers and rushing mountain rivers.

Now three to four million visitors come to the Banff area every year.

Thirteen of the early buffalo there were donated from the Bedson herd by Sir Donald A. Smith, Lord Strathcona, purchased from Samuel Bedson, warden of the prison near Winnipeg.

They originated with James McKay of Winnipeg, who rescued calves during Metis hunts in the western plains of Canada. Three more—two cows and a bull—were donated by Charles Goodnight from his Texas herd.

A display herd of buffalo at Banff was one of its early tourist attractions, beginning in 1885. It persisted there for over 100 years, but is now being replaced by free-roaming buffalo in the back country of Banff National Park. ©Parks Canada / Banff.

Buffalo were kept for over 100 years in a small enclosure near the railroad. Until 1997 the buffalo herd was a popular tourist attraction.

But it had served its purpose. It was time to move on.

The dream was always for free-roaming buffalo in the backcountry of Banff National Park, as in prehistoric days when they were hunted by indigenes people.

“Homecoming to Banff” planned

Twenty years went by before the 5-year restoration plan was ready.

The historic “Homecoming to Banff” was planned as a high-tech, scientific experiment producing a wealth of detailed research data.

One of the first questions Parks Canada personnel asked was: How do you get Plains buffalo to bond to a Rocky Mountain home?

Seasoned buffalo handlers were in agreement: Buffalo cows from the plains need to calve in the mountains before they will accept it as home. Otherwise, any self-respecting buffalo herd will travel until they reach a place they like—breaking down fences and trampling crops as needed to get there.

Cattle ranchers voiced concerns that buffalo would escape, damage property and spread disease to livestock. In response, the planners included a hazing zone, recapturing, and as a last resort destroying the animals. If they detect disease they agreed to cull the herd.

Goals of reintroduction

The reintroduction of bison to Banff brings back a keystone species that will:

• Support ecological integrity;

• Contribute to bison conservation since plains bison are only protected in three herds in less than 0.5% of their original range in Canada;

• Reconnect indigenous peoples and bison; and

• Create new opportunities for visitors and Canadians to learn about the ecological and cultural importance of bison.

Reintroduction of bison included a Blessing Ceremony with staff and Indigenous people in Banff National Park. Photo courtesy of ©Parks Canada / Banff National Park.

The Parks Canada five-year plan includes:

Year 1 and 2 (2017-2018) involved a soft-release in Banff National Park.

The soft-release plan includes bringing young pregnant cows with a few bulls to a desirable, but remote, mountain valley in Banff National Park, Alberta, Canada, where they’d give birth to their first calves under the watchful eyes of biologists.

Carefully selected, the young herd came from the disease-free, extensively-tested and vaccinated herd at Elk Island National Park, which is just east of Edmonton, Alberta, in the Great Plains.

They were to be held for “summer vacation” in a small enclosed pasture in remote Panther Valley and fed hay that first winter. The following spring they calved a second year in the small “soft release” pasture of their new home. Gradually fences and barriers were moved giving access to an increasingly larger area.

Years 3 to 5 (2018-2022) the herd will at last be free to range—free-roaming it’s called.

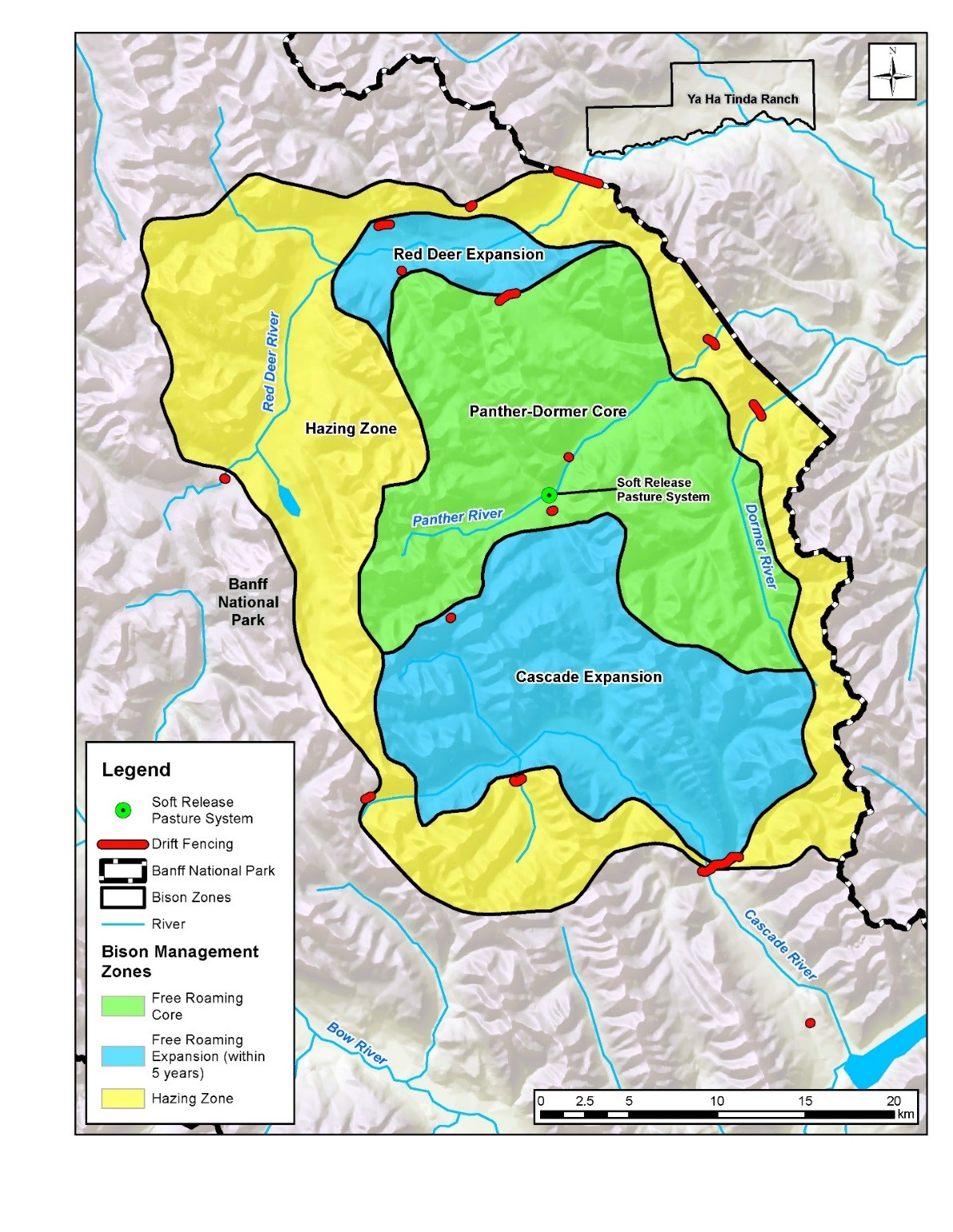

They will range through the east part of the park where they will continue to live year around from then on in a wild state. The barriers are let down between the initial area to the Red Deer and Cascade Rivers expansion. A larger “Hazing Zone”

The Panther and Dormer River Valleys in the eastern part of Banff National Park form the core of the initial reintroduction zone, spanning 1200 km2 (463 mi2; green). Within this is the small Soft Release Pasture System (green dot). During the 5 years the Red Deer and Cascade Expansions (blue) will be added. The Hazing Zone is yellow. Short stretches of wildlife-friendly drift fencing (red) encourage bison to stay within the reintroduction zone—and outside the hazing zone—while allowing other wildlife to pass safely in and out of the park. Map courtesy of ©Parks Canada / Banff National Park.

The rangers at Parks Canada brought it all together just in time to celebrate Canada’s 150th anniversary year.

On April 25th, 2017, they loaded 16 buffalo—12 two-year-old females and four two-year-old bulls—into shipping containers on trucks in Elk Island National Park and trucked them to Banff National Park.

There each shipping container—containing three or four husky buffalo—was picked up by helicopter and, dangling through mountain valleys by a metal cable, called a longline, was airlifted to their new soft release pasture in the Panther River valley.

There in grassy river bottom lands the shipping containers were dropped gently down at the edge of the forest.

Parks Canada personnel opened the containers and the buffalo burst out on the run.

Sixteen buffalo were loaded in shipping containers at Elk Island National Park and trucked to the Banff park. A helicopter then airlifted the containers to the soft-release pasture in a remote part of the park where they were opened and the bison released. Video courtesy of ©Parks Canada / Banff National Park.

It was a remarkable moment as the buffalo charged into the verdant green mountain valley, looked around and began eating.

Ten healthy bison calves were born in the soft release area of Banff National Park’s remote backcountry before the end of May.

The new calves brought the herd number to 26. They mingled with the herd, napping in the sun, running and playing together.

In July, the soon-to-be-wild herd was moved from their 6-hectare winter pasture into a 12-hectare (30 acre) summer pasture, which includes tasty mountain grass, instead of the dry hay they are used to.

They drank from a clear, flowing river, instead of a cattle trough, and for the first time ever faced mountains to climb and explore.

This was a big change for these young animals. There is no running water or steep hills to climb in the safe plains pasture where they grew up in Elk Island National Park.

These new arrivals represent the future of buffalo restoration in Banff. They are part of the larger vision to reintroduce wild bison, and their gradual introduction to the park will help this herd anchor to the landscape and adopt it as their new home.

The Parks Canada team is committed to involving the public in the buffalo reintroduction effort. A well-considered, illustrated blog provides students and adults with fascinating details.

People throughout the world are being urged:

“Follow the herd from home! See what life is like for the calves by watching our new webisode on YouTube. Share it with your friends and family on social media.”

Herd dynamics—Cliques, leaders and rebels

“The herd arrived in Panther Valley in early February, and they’re settling into their new home. Part of that process is figuring out who’s who in the herd. We’ve been keeping a close eye on them and starting to notice personalities starting to form.

“In the past few weeks, Cow #12 has caught our attention. She’s normally the first cow to feed which could be a sign that she’s becoming a leader in the group. This is pretty exciting because bison tend to organize themselves into matriarchal societies. They are normally led by older females who know the way to the best food and watering holes.”

The soft-release bison pasture is located in one of the most remote parts of the park in Panther Valley. It takes two days to get there on foot, ski or horseback from any direction.

It takes two days to get to Panther Valley on foot, skis or horseback. The team takes turns staying in a nearby cabin, feeding hay, and monitoring the herd. Photo courtesy of ©Parks Canada / Banff National Park.

Members of the Bison team take turns staying in a nearby cabin. They feed hay, monitor health and track each of the bison. Other tasks include chopping wood, wildlife observations, care of horses and checking remote cameras.

Blogging: Spring 2018

“On a chilly week in March our team of veterinarians and conservation specialists flew to the bison paddock in the remote Panther Valley of Banff National Park to start a big task: radio collaring the adult female bison and giving ear tag transmitters to their calves.

“May 6, 2018. Buffalo are already shaping the landscape. Called keystone species, or ‘ecological engineers,’ they alter the ecosystem around them and benefit a huge number of other creatures, just by their natural behavior.

“Expected benefits of grazing buffalo:

• More forest openings for meadow-loving birds and other small mammals.

• Well-fertilized grass for other grazers like elk and deer.

• More seasonal wetland habitat for amphibians due to bison wallows filling with water.

• A new food source for a community of creatures including bears, wolves, ravens, and coyotes.

“Horseback riders gently push the buffalo to help them explore key grazing area of their new home range. In April our core bison team travelled to Montana to get more practice in using the technique called ‘natural stockmanship,’ a low-stress approach to interacting with herd animals, like bison.”

In Montana they worked with experienced cowboys who handle over 1,000 buffalo, moving them periodically between pastures. The Banff team hit the road to practice low-stress handling skills they’d need to guide their own small buffalo herd to areas of good grazing.

Meanwhile the animals remained in the smaller enclosure until summer, when the gates would open.

“July 23, 2018. First two of new crop of calves have arrived. Bison calves are born with bright reddish fur – giving them the nickname of “little reds.” After a few months, they start to look more like the chocolate brown of their parents.

The cows calved twice within the fenced-in soft-release pasture to help them bond to the area. Photo courtesy of ©Parks Canada / Banff National Park.

“This is the herd’s second calving season in the soft-release pasture, and it’s one of the main ways we’re helping them bond to their new home range. Bison tend to return to the same areas to calve each spring. By holding them for two calving seasons in the heart of the reintroduction zone, we hope that the herd will adopt this area as their annual calving ground.

“August 2, 2018. Bison have returned to the backcountry of Banff National Park. For the past year and a half, Parks Canada has cared for the animals as they adapted to their new home in Panther Valley in a remote area of Banff National Park. They were held in a soft-release pasture to anchor them to the location and help prepare them for their new life in the mountains.

“Now, the bison are ready for the next phase: free-roaming. We released the herd from the soft-release pasture and bison are now free to roam a 1200 sq km reintroduction zone in Banff’s eastern slopes. They will start to fulfill their role in the ecosystem as a “keystone species,” by creating a vibrant mosaic of habitats that benefits bugs to birds to bears, and hundreds of other species.

“We will use GPS collars to track their movements across the landscape and their interactions with other native species. Over time, we hope to learn how bison integrate into the ecosystem and understand their impact on the surrounding landscape.

“At the end of the pilot project in 2022, we will evaluate the success of the project and determine the future of bison restoration in Banff.

“On July 29, 2018, we opened the fence of the soft-release pasture and released the herd to roam the 1200 sq km reintroduction area in Banff’s eastern slopes.

“We spent 1.5 years helping these animals learn to adapt to their new home. Now the tables have turned, and we have started to learn from them. They are already teaching us new things about what it means to be a mountain bison.

“On release day, we opened the gate around noon and waited for the bison to find the opening. And we waited. And finally, around midnight, we captured the herd on camera crossing the fence-line and moving through the release corridor we built for them.

“The next morning, we awoke to find the soft-release pasture empty. Bison had finally found their freedom. We sent our team into the field to monitor the herd using telemetry to trace their radio collar signals. When we picked up their signals, we were surprised with what we found.

Picking up the signals of the released collared bison, staff were surprised to find them high on the mountain side. Photo courtesy of ©Parks Canada / Banff National Park.

“Instead of following the valley bottom like we expected, the herd travelled and stayed high on the mountainsides, grazing and bedding in the uppermost fingers of vegetation that edge into the rocky slopes. We watched as they dipped down to the creek for a drink and then returned up the slope to bed down. Two pregnant cows then climbed even higher to an alpine lake where they gave birth to the first wild calves born to the free-roaming herd—bringing the herd to 33 animals. Two other cows with newborns summited a nearby ridge overlooking the soft-release pasture.

“This is a new experience for these bison, as they have never lived without fences. They are learning their new boundaries, getting their first views of the landscape before them, and testing their mountain legs.

Cows and calves raised with water tanks cross river for first time. Photo courtesy of ©Parks Canada / Banff National Park.

“The vast majority of the herd seem content within 6 km of the initial release site, while a few bulls have ventured into a nearby valley and one bison bull has left the core reintroduction area and is currently on Province of Alberta lands just east of the national park. We continue to follow his movements closely, and may try to capture him if this walkabout takes him further east.

“Almost a month after the release of 31 bison into Banff’s backcountry, the majority of the herd has remained within 15 kilometers of the release site.

“However, two bulls ventured eastward well beyond the park boundary and were within a day’s walk from private lands. Our reintroduction plan and commitments to provincial stakeholders, promised that we would keep bison out of these areas.

“We considered capture and relocation for the first bull, but concluded that it was not feasible due to several factors including:

• The speed at which the bull was moving east,

• The main herd was also travelling northeast into challenging terrain where hazing efforts would be less effective—we needed to focus resources on managing the main herd,

• Wildfires limited the availability of helicopters able to capture and transport an animal as big as a bison, while thick smoke reduced visibility, and

• We had to consider potential risks to the bison team in attempting to immobilize and move bison under these constraints.

“In the end, we made the tough decision to euthanize this first bull.

“Fortunately, several days later, we were able to successfully capture and relocate the second bull, to a temporary home in Waterton Lakes National Park. This was a very challenging operation that involved a contracted capture team netting the bison from a helicopter.

“We then immobilized it, and rolled it into a custom built bison-bag that allowed us to sling the immobilized bison under a large helicopter without compromising its airway, just long enough to lift it into a nearby horse trailer for transport.

“Decisions to relocate or destroy an animal are difficult for our team and are made only after we have considered all other options. These two bulls were determined to travel eastward past any obstacles in their way, and they taught us a lot. We have modified our herding techniques and have expanded some strategic drift fencing.

“September 27, 2018. The herd is currently doing well and staying high on the mountainsides to forage on fresh vegetation and stay out of reach of biting flies.

“Since we released the herd, at least 4 more calves have been born in the wild! The herd now consists of 10 adult females, 4 adult bulls, 10 yearlings, and now 9 calves, totaling 33 animals. These bison appear to be settling into their new home and all animals are within the core reintroduction area.

“The main herd has spent most of their time in the Snow Creek Valley following their release into the wild. They have been grazing, bedding and raising their calves at high alpine lakes and on mountain slopes in one of the most spectacular areas in Banff’s backcountry.

“We want to help them discover key areas in their new range so they will be aware of seasonal grazing opportunities throughout the reintroduction zone. One place we wanted to show the herd is the Lower Panther Valley—a landscape of rolling meadows that is snow-free most of the year and offers some of the best fall and winter grazing in the area.

The staff uses low-stress skills to gently encourage the herd to discover key areas in their new range which offer good fall and winter grazing. Photo by Dan Rafla, ©Parks Canada / Banff National Park.

“The team used the low-stress skills learned from the Montana cowboys, with a combination of staff on foot, horseback and helicopter to gently herd the animals south toward the Panther Valley.

“On September 4th, we successfully encouraged the herd to calmly walk about 15 km southwards; eventually ending up right back where they started—in the soft-release pasture.

“It was an incredible sight to see 27 bison walking single file along ridges, edging along talus slopes and winding through willows in the valley bottom.”

Winter scene of buffalo at edge of woods in Banff National Park, May 19, 2020. Photo courtesy of ©Parks Canada / Banff National Park.

_____________________________________________________________

Next: Part 2. Return of Wild Buffalo to Banff National Park

_____________________________________________________________

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog