Clearly, the buffalo were headed for extinction. No one seemed to care.

The “bottleneck”—as it’s been called—drew even closer each year after the last great buffalo hunt on the Great Sioux Reservation in 1883.

The low point came in the 1890’s, or perhaps later, around the turn of the century. That was when the “safe and protected” Yellowstone Park herd, estimated at 200, was suddenly decimated by poachers seeking trophy heads.

Fewer than 25 buffalo, well hidden in remote and rugged canyons, survived that slaughter in Yellowstone Park.

The species was nearly choked off completely at that time. Even the few hundred remaining seemed destined to dwindle.

William Hornaday voiced his despair over the buffalos’ nearly-inevitable extinction in his 1889 book, “The Extermination of the American Bison.” He wrote:

“The wild buffalo is practically gone forever, and in a few more years, when the whitened bones of the last bleaching skeleton shall have been picked up and shipped East for commercial uses, nothing will remain of him save his old, well-worn trails along the water-courses, a few museum specimens, and regret for his fate.”

Hormaday despaired that ‘when the whitened bones of the last bleaching skeleton were picked up and shipped East’ the only memory of buffalo would be trails to water, regret for his fate, and a few specimens in museums. Photo National Park Service.

As head taxidermist at the Smithsonian Museum in Washington, DC, Hornaday worked hard to collect dead buffalo specimens. He believed it was his duty to help the nation’s most important museums show future generations how magnificent the buffalo had once been.

Difficulties in raising Buffalo

Some ranching families stepped in to save a few buffalo calves, but their efforts were scattered and uncoordinated. Likely most did not see themselves as important links in the void of trying to save an entire species.

Raising a viable herd became more and more difficult as years went by. Even if fragile young calves survived their initial crisis of bonding and grew to adulthood. Even if their saviors found adequate pasture not needed for other farming.

There was no market for buffalo. No one wanted to buy them. They were difficult to handle, and worst of all, they quickly outgrew their boundaries.

When too crowded, they simply broke through confining fences and caused havoc in the community. Angry neighbors waved pitchforks over ravaged crops.

No government program advocated their rescue. Even toward the end, no experts reached out to save the majestic buffalo.

When the owner of a small herd died or lost his land, the herd had to be disposed of—and usually quickly. The buffalo herd was multiplying fast and pasture boundaries were easily breached.

All too easily came the obvious solution—at the butcher shop. Slaughter the entire herd, when heirs could no longer handle the buffalo. End of problem.

But a few feeble glimmers of hope shown through.

Actually, there were five.

These five family groupings get the credit—and our gratitude—for establishing viable buffalo herds that grew and multiplied. They are:

1. Samuel Walking Coyote and herd purchasers Charles Allard and Michel Pablo in western Montana;

2. James McKay and neighbors in Manitoba, Canada;

3. Pete Dupree and herd purchasers, the Scotty Philips in South Dakota;

4. Charles and Molly Goodnight of Texas;

5. Buffalo Jones of Kansas.

Separately, these people brought buffalo back in significant numbers for survival—onto the western plains and grasslands where they have always thrived so well.

These were ordinary people—westerners, ranchers, even buffalo hunters—with boots on the ground. Or more specifically, in over half the cases—moccasins on the ground.

Separately, five family groups of ordinary people in their own communities captured wild calves, raised them into viable buffalo herds and brought the animals back from near extinction. Photo by Brian Miller.

The first three of these five family groupings had Native American roots. The last two were white ranching families.

Without them, buffalo would have gone the way of the passenger pigeon.

William Hornaday’s dire prediction could have proved true. The last whitened bones of the last bleached buffalo skeleton could have been shipped out for fertilizer.

Sam Walking Coyote’s trek over the Rocky Mountains

Samuel Walking Coyote of the Pend d’Oreille Indian Tribe in western Montana had no intention of raising buffalo—or of helping to save the species.

After all, he came from west of the Continental Divide—not the historic home of Plains buffalo.

But there he was with eight half-grown buffalo calves on the east side of the Rocky Mountains and a longing to return back home.

He wasn’t sure he’d be welcome. He knew he might already be in trouble with the Fathers at the Mission. But he hoped the calves might be viewed as a nice gift for them.

Walking Coyote lived with his Flathead wife on her reservation in western Montana.

There are several versions of Walking Coyote’s story. But as with most of the other heroes of this buffalo saga, he could neither write, nor read his own account of what happened.

In the summer of 1872 he decided to ride east across the Rocky Mountains on old Indian trails over the Continental Divide and spend the winter hunting buffalo in Montana’s

He made the trip and had a fine time hunting buffalo with Blackfeet hunters who scouted far up the Milk River close to and likely across the border into Canada.

Orphaned calves bonded with the horses and followed the Blackfeet hunters home. Photo by Chris Hull, SD Game, Fish, Parks.

After one hunt, eight orphaned buffalo calves came into their camp and bonded with the horses. They stayed around the rest of the winter and ate hay with the Native horses.

During this time, Sam Walking Coyote fell in love with a young Blackfeet woman from the tribe, and arranged with her family to marry, ignoring the fact he already had a Flathead wife.

Two wives were permitted in both tribes. Often it happened through necessity, as when an impoverished widow was brought into her sister’s family for protection.

But Walking Coyote knew very well that the Jesuit priests at St. Ignatius Mission would be angry to discover his second wife.

He longed to go home, and was persuaded by a friend that the buffalo calves would make a fine gift for them, as a way to make amends.

So, one pleasant spring day, after some of the snow had melted from the high trails, Walking Coyote and his new wife set off west to cross the Rocky Mountains with their little caravan, several pack horses, dried buffalo meat and the eight buffalo calves.

It was hundreds of rugged miles travelling over and up and down the Continental Divide.

The trail they followed was long and treacherous, up one steep mountain pass and down the next, alternately leading and driving their little herd, scrambling over rocks and fallen timber. They waded through icy rushing rivers and deep snow banks.

Sometimes they tied the smaller calves onto the backs of horses, when they were too tired to walk.

Grass for the livestock became scarce and there was no game to eat. Two of the calves died along the way.

At long last they came out on the west side of the mountains and made their way down onto the Flathead reservation.

A man named Que-que-sah is quoted in an interview by the 1942 W.P.A. Writers’ Project, as saying, “I was in the village St. Ignatius that day in 1873, when [Walking Coyote] rode in with his pack string. He had four buffalo calves on pack ponies. I recall that they were rather small. One, in particular, was very young and weak.”

As it turned out, the priests did not look with favor on Walking Coyote, his new wife, or even the gangly buffalo calves. They scolded him severely, and he was punished by his first wife’s tribe.

Banned from the mission, he moved his buffalo farther on down the valley. There they became pets and objects of great interest to the Native people.

“We were all greatly interested in the welfare of Samuel’s calves,” recalled Que-que-sah. “I think that every Indian on the reservation looked upon this little herd as the last connecting link with the happier past of his people. I know we all protected them, wherever they were grazing.”

The Native community grew committed to the little herd’s survival, writes Ken Zontak in “Buffalo Nation.”

Interestingly, the west side of the Continental Divide was not the natural home of Plains buffalo. Historically buffalo lived only east of the Divide and did not come across the Rockies.

But the six calves thrived there on the rich mountain grasses and multiplied.

By 1884, Sam Walking Coyote owned a herd of 13 tame buffalo.

Pride of the community: Walking Coyote’s small herd wandered unmolested on the Flathead Reservation. Photo by SDGFP.

“The small herd wandered about the Flathead Reservation unmolested and caused much excitement during calving time,” wrote Zontak.

“Their bison served as the pride of the community, with Sunday observers visiting after church at Saint Ignatius to view the icons of a bygone era.”

However, as the herd increased, the huge animals broke down fences and destroyed crops. They were becoming a nuisance to Sam’s neighbors.

He decided to sell them to Charles Allard and Michel Pablo, friends of his and ranchers in the valley, who were interested in raising buffalo.

The Canadian Winnipeg Tribune stated that Walking Coyote had a prospective Canadian buyer, but negotiations broke down when he named his price–$250 a head.

The Winnipeg newspaper reported, “Donald McDonald, the last man to represent the Hudson’s Bay company on United States territory, entered into negotiations to purchase that little herd of the last plains buffalo remaining alive.

“But C.A. Allard and Michel Pablo, two Montana ranchers, made a deal with Walking Coyote, at $250 a head for the animals.

“Walking Coyote insisted on having actual money. He refused to accept a cheque. Allard and Pablo were busy counting out the greenbacks into piles of $100, each of which was placed under a stone, when they saw a mink.

“Instantly, Walking Coyote and both the ranchers went after the mink, and for some minutes forgot the piles of money, to which they hurried back, to find it safe, with a lone Indian looking at it with covetous eyes,” according to the Winnipeg Tribune (Dec 22, 1922). .

Both the new partners had Native American mothers, and Pablo’s wife was Salish. They had rights to run buffalo free on Indian lands.

Pleased with their purchase of buffalo, they bought 26 more, along with 18 cattalo—half buffalo, half cattle—from Buffalo Jones of Kansas.

A healthy herd, it multiplied and by 1895 they owned 300 head of buffalo grazing them on the same free Indian Tribal ranges.

Then Allard died unexpectedly at age 43, and the herd was divided. Allard’s half went to several buyers. Some went to Yellowstone Park to begin replenishing that herd.

Michael Pablo and his Montana buffalo herd. It soon multiplied to over 300 head—and more.

By 1906, with his herd doubled again to 300, Pablo learned the Flathead reservation was opening to homesteaders. He’d lose his free range there. He offered to sell the whole herd to the US government for $200 per head, but Congress turned it down as too expensive.

Eventually he was able to sell his entire herd—redoubled again to over 700 head—to the Canadian government. Price: $250 each including freight by rail.

James McKay, a Canadian Métis hunter

Frequently, James McKay, also known as Tonka Jim, joined the twice-yearly Red River Métis hunts.

Living near Winnipeg, Canada, Tonka Jim McKay began his career working for the Hudson Bay fur trading company, as did his Scottish Highlander father. His mother, Margarete, was Métis.

James McKay, a Metis fur trader, became a politiician, translator and guide. On Matis buffalo hunts, worried at the scarcity of buffalo, he began saving calves.

He served as postmaster and clerk, managed small trading posts mostly in what are now southwestern Manitoba and southeastern Saskatchewan, and established two Hudson Bay posts in US territory.

Moving into Manitoba politics, he represented the Métis people and helped them negotiate treaties. He served Manitoba as president of the Executive Council, Speaker of the Legislative Council and Minister of Agriculture.

With his knowledge of the prairies and indigenous people, McKay also excelled as a frontier interpreter and guide. Often he wore the popular Métis attire—a hooded blue capote with pants of homemade wool, moccasins and a colorful sash.

With each buffalo hunt, McKay noted his friends were going farther west and south into Montana with their Red River Carts to find buffalo herds.

Tonka Jim McKay enjoyed wearing the popular Metis garb: Hudson Bay coat with hood attached, tied at waist with colorful sash. Voyageur Capote Coat with Nancy Gouliquer, Manitobamuseum.ca.

With the massive kills of their large Métis parties, the Plains buffalo were quickly disappearing from Canada, as well as the northern states.

At the same time the constant hunting pressure pushed the Wood Buffalo farther and farther north in Canada.

McKay became alarmed at the scarcity of buffalo. On an 1873 Métis hunt he captured three calves with the help of friends and the next year, another three, bonding them with nurse cows on his Deer Lodge ranch some 28 miles west of Winnipeg.

He purchased a few more calves from Native hunters who went west to hunt and returned through Winnipeg.

In about 1877 McKay sold five calves to Colonel Sam Bedson, a penitentiary warden, for $1,000. Bedson’s buffalo thrived. By1888 he owned nearly 80 full-breed buffalo and 13 half-breeds.

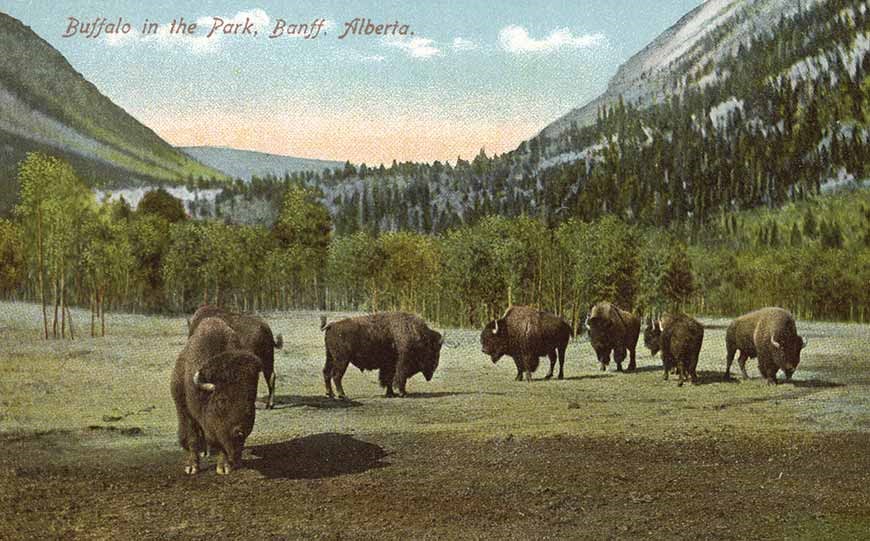

Exhibition herd in paddock at Banff National Park, Alberta.

Unfortunately, in 1879, just as his buffalo herd was gaining some natural increase, Tonka Jim McKay died at the age of 51.

After his death some of McKay’s buffalo went to the Canadian government. Others went to another neighbor who then donated all of his 13 buffalo to Rocky Mountain Park in Banff for a special exhibition herd.

Charles and Molly Goodnight in Texas panhandle

When Charles Goodnight was 11, he moved to Texas from Illinois with his parents—who got caught up in the ‘Texas Fever’ of the 1840’s.

He fit right in, growing up on the new frontier, and took on several ranching positions before settling down as a rancher himself.

One of these jobs was trailing Texas cattle north to market. With drover Oliver Loving, he became well-known for blazing the Goodnight Loving Trail to the railroads in Cheyenne, Wyoming.

The trail proved a success. Over the years hundreds of thousands of cattle were driven up the Goodnight Loving Trail from the Southern Plains to Cheyenne and then shipped by rail to eastern markets.

Charles Goodnight, a prominent cattleman of the Texas Panhandle, “approached greatness more nearly than any other cowman of history,” according to writer J. Frank Dobie.

Goodnight also killed his share of the wild buffalo that covered the Texas plains and competed with cattle for grass.

One day while buffalo hunting, he discovered that very young buffalo calves tired quickly and dropped behind when the herd stampeded. He decided to capture some of them.

“The first time I went out to get buffalo calves, I moved them up a little until three of the calves fell behind. I cut them off and they followed the horse home and into the corrals,” he recalled years later. “When night came I roped them and put them to their foster mothers, Texas cows.”

A few days later he cut out two more in the same way, but thought he needed one more.

“I wanted six, so I went out again and found one calf about twenty-four hours old. I scared the cow off some distance, and put the calf on my horse. But the cow returned and attacked me so viciously that I had to kill her to save my horse. I felt badly over it then, and the older I get, the worse I feel about having to kill that cow.”

Goodnight mothered up the six calves with range cows, and when they were eating well he left them with a friend, who agreed to care for them on shares for half the profits.

But when he returned, he was disappointed to find the friend “got tired of the business and sold out, and never even gave me my part of the money.”

In 1870, Goodnight married Mary Ann ‘Molly’ Dyer, a teacher from a small town west of Fort Worth, and began building up his own ranch in the new country of the Texas Panhandle.

Goodnight credited his wife Molly for renewing his interest in raising buffalo calves.

Molly realized the buffalo were fast disappearing and urged her husband to help save them.

He gave his wife credit for renewing his interest in raising buffalo.

“In the spring of 1879—to be exact, May 15th—at my wife’s request, I started out to look for some young buffalo. At last I found a few younger ones in Palo Duro canyon, and roped them from horseback.

“The month following, W.W. Dyer, my wife’s brother, caught two young females. From this start we have now a herd of 45 purebred buffaloes”

By then Goodnight owned many cattle and claimed 60,000 acres of pasture. He set aside 600 acres for a fenced buffalo park.

Together Charles and Molly Goodnight continued building up the first Texas Panhandle ranch, the JA Ranch, in the Palo Duro Canyon of the Texas Panhandle.

There they lived “the good life” in a Victorian-style home, and Mollie cooked for and entertained heads of state, hungry cattlemen and cowboys, as well as the Comanche leader Quanah Parker.

Mollie Goodnight taught children in the bunkhouse. The cowboys slept there at night, and she moved their things aside for school during the day. The house had electricity and sheltered hundreds of ranch workers and cowboys over the years.

Molly Goodnight was known as compassionate, one of the few women living in the Texas Panhandle. She is given much credit for saving the original southern buffalo in their purest form.

At one point the Goodnights obtained two buffalo—a yearling and a two-year-old—from Colonel B.B. Groom’s ranch and sent two cowboys to pick them up.

Palo Duro Canyon of the Texas Panhandle, where the Goodnight buffalo herd hid out for years.

One of the cowboys, Mitch Bell, “goodhearted veteran of the Palo Duro,” recalled that they took a camping outfit, wagon and horse feed, since they would be out three nights.

Tied to the wagon was Old Blue, a ranch steer.

Bell said they roped and dragged the two buffalo up and necked them tight to Old Blue.

“Then we turned Old Blue loose, and he was the maddest steer I ever saw. He jerked the little one down, drug him a long-ways, and I thought was going to kill him, sure. But finally he got up, on the same side with the other buffalo, and he stayed there all the way back to the ranch.”

A pair of Goodnight bulls with authentic southern genes. Caprock Bison Release, Earl Nottingham.

Goodnight began experimenting with cross breeding in 1884, crossing buffalo with Polled Angus and Galloway cattle, and developed a herd of sixty cross-breds he called cattalo.

Their buffalo herd continued to increase and by 1910 was reported as totaling 125. On January 1, 1914, the total was 164, of which 35 were bulls, 107 were cows, and 22 were calves. The highest number the Goodnights reported was about 250 head.

The Goodnights donated and sold buffalo directly from their herd to Canada, Germany, Nevada, New Hampshire, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, Montana, New Mexico and New York. The genetics of the few remaining buffalo were becoming quite mixed.

Many of their donations to zoos and parks helped to start new buffalo herds.

________________________________________________________________

Next: Part II-Saving the Buffalo from Extinction

______________________________________________________________

.

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog