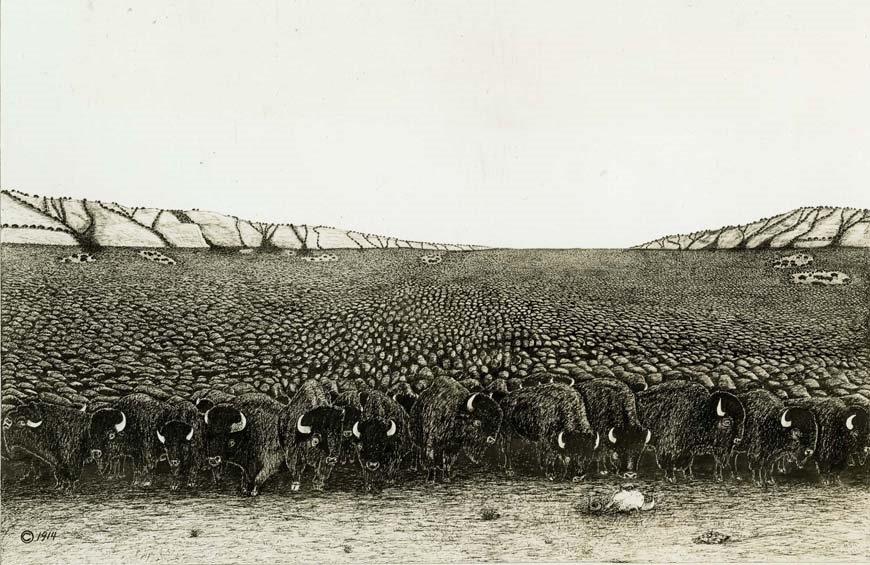

One eastern artist’s idea of what a big herd of buffalo might look like. The Buffalo Book, David A Dary.

Descriptions often had it that the hills were “black with buffalo as far as the eye could see.”

Explorers and travelers often tried to describe and estimate how many buffalo they could see from a single vantage point.

On viewing a large herd of cattle one day, a Canadian named John McDougall was amazed to learn there were 23,000 head in the herd before him. He said that cattle herd in one small valley was far smaller than the immense buffalo herds he’d seen spread out over a dozen hills and flats in the plains.

Comparing herds from memory, he ventured, “Many times from hills and range summits, I had seen more than half a million buffalo at one time.”

During their journey from St. Louis to the Pacific Ocean and back, Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark described their astonishment at the huge buffalo herds they encountered through the Dakotas and west as far as the Rocky Mountains. Always there was plenty of meat for their hunters to feed the boat crews—until they actually reached the mountains—when they were sometimes desperate enough to eat their horses.

It was on their return journey, in August 1806—when they saw their largest buffalo herds—travelling through South Dakota’s White River country. They reported in their journals,

“We are convinced that 20,000 would be no exaggerated number—more than we had ever seen before at one time!”

A North Dakota railroad surveyor once stood on a high point from which he added up what he saw:

“For a great distance ahead every square mile seemed to have a herd of buffalo upon it. Their number was variously estimated by members of the party, some as high as half a million. I do not think it any exaggeration to set it down at 200,000.”

One traveler, Thomas J. Farnham, crossed Kansas for three days on the Santa Fe trail in 1839, driving a team all the way through what appeared to be one large migrating herd.

He wrote, “We travelled at the rate of 15 miles a day—15 times three days equals 45. Take 45 times 30 [miles across] and you get 1,350 square miles . . . so thickly covered with these noble animals, that wen viewed from a height it scarce afforded a sight of a square league of its surface.”

Colonel Dodge reported to William Hornaday that he drove 25 miles through a herd migrating north along the Arkansas River. He estimated it to be at least two miles wide, averaging 15 to 20 buffalo per acre.

Hornaday repeated Dodge’s figures, estimating that he had seen 480,000 buffalo. When he added the herds Dodge saw earlier that day from the top of Pawnee Rock, his day’s total reached 500,000, or half a million head of buffalo.

Hornaday speculated that if Dodge’s herd had been 50 miles long by 25 miles wide, “as it was known to have been in some places”—it would have contained 12 million head.

Deducting two-thirds of this—in figuring a possible wedge shape in the front—he came up with over four million in the herd, “which I believe is more likely below the truth than above it.”

Another question often asked is, “How many millions of buffalo were here when the first Europeans arrived?”

Speculations ran high, and people believed them all. Obviously there were so many buffalo, how could the number be exaggerated?

One early estimate that took hold, was that of Earnest Seton, a famed Canadian naturalist. Seton estimated the square miles of probable buffalo range by their carrying capacity, and came up with 60 million or even 75 million buffalo that grazed the North American grasslands at one time.

These totals persisted until recent times, when range specialists began saying, “Wait just a minute, there. Let’s do the math again.”

Turns out Seton estimated the heavily-used buffalo range at about three million square miles, double what today’s experts can claim.

Today’s range specialists insist the buffalo grazing the fringes of Seton’s enormous chunk of pasture were few to non-existent.

The California scientist Dale F. Lott, who grew up on the National Bison Refuge in Montana objected to Seton’s figures in his book American Bison: A Natural History. He argued that Seton

drew a line around every reported location of bison in North America, including most of the Rocky Mountains and all of Idaho, where bison were known to be rare to nonexistent.

Lott said Seton then calculated the entire region at close to full carrying capacity, even though buffalo were likely rare on the broad fringes of that range.

Llewellyn Manske, PhD, Research Professor of Range Science, at the NDSU Research Extension Center in Dickinson, ND, reports that the known buffalo ranges did not contain 3 million square miles, but only about 1.2 million.

This included lands from the foot of the Rocky Mountains to the Appalachian Mountains and from southern Texas to the Canadian Shield in Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta—all of the tall grass, mixed grass and short grass prairies and parts of the eastern deciduous forest and aspen parkland, for a total of 575,000 square miles in the Great Plains and 650,000 square miles in the central lowlands.

Manske says the peak buffalo population was likely about 30 million.

Lott concludes, “About all we can confidently say is that primitive America’s bison population was probably less than thirty million—perhaps on average three to six million less.”

That was still a lot of buffalo!

(Compiled from many sources for Buffalo Heartbeats Across the Plains, by FM Berg, 2018.)

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog