In 1907 the Michel Pablo herd from western Montana began arriving in Canada.

At their end of the railroad, Canadians cheered the buffalo’s arrival.

They knew they had scored a coup in getting “the finest buffalo herd in America,” as William Hornaday, president of the new American Bison Society, called Michal Pablo’s half-wild herd from Montana.

Pablo’s buffalo arrived in Canada, weary from riding 3 days, 1,200 miles, in special boxcars switched over five railway lines. The Canadians assured Pablo they would buy his entire herd—bulls, cows and even newborn calves—at his price of $200, in addition to shipping charges of about $45.

The first two shipments in 1907 made it in good shape. Such a long shipment of a herd that large had never been attempted before.

Pablo initially estimated that he owned about 400 bison, but as it turned out he had over 700. It was not easy to get them loaded on the train, however. What he thought would be a roundup lasting one summer or two, stretched out for five years.

The Canadians must have watched anxiously as Americans in the US, chagrinned at their loss, began offering higher payments for what was left, even to a reported $700 per animal.

Their contract called for Pablo to deliver the buffalo to the railhead at Ravalli, Montana, where they could be loaded on railway cars and shipped to Canadian destinations. It was a 3-day train ride of 1,200 miles, travelling over five different railway lines.

Because it took so long to load the buffalo, some stood in railway cars on the siding for up to 14 days before all the cars could get loaded.

Pablo received an initial down payment of $10,000 from Canada and began planning a 2-year roundup and shipments for 1907-1908. He was deemed a very wealthy man by his Native friends, but his expenses in getting the buffalo to and into the railroad cars turned out to be large.

Michel Pablo’s first shipments in 1907 to Canada looked pretty good, and even by the 4th of July in 1909 the Daily Missoulian in Missoula, MT, could report:

“With the shipment Wednesday of nearly 200 buffalo from Ravalli, Montana, to Canada,

all but the outlaw remnant of the largest herd of wild bison in the United States were removed from their native heath to the limited confines of a foreign park.”

Pablo had at first considered driving his buffalo herd north across the border with the cowboys he hired, but chasing them the 50 miles to the train station in Ravalli proved how impossible this could be.

Unloading at Elk Island Park

In Canada, Pablo’s buffalo were supposed to be unloaded at Wainwright, Alberta, where land was set aside for a new national bison park. But Pablo’s first shipment arrived before its buildings and fences were ready.

Luckily, Elk Island Park was conveniently located near a railroad station, a short distance east of Edmonton. Built as an elk preserve as its name suggests, it was entirely surrounded by sturdy 10-foot fences.

Pablo’s first 400 buffalo were unloaded at Elk Island Park, just east of Edmonton, in 1907.

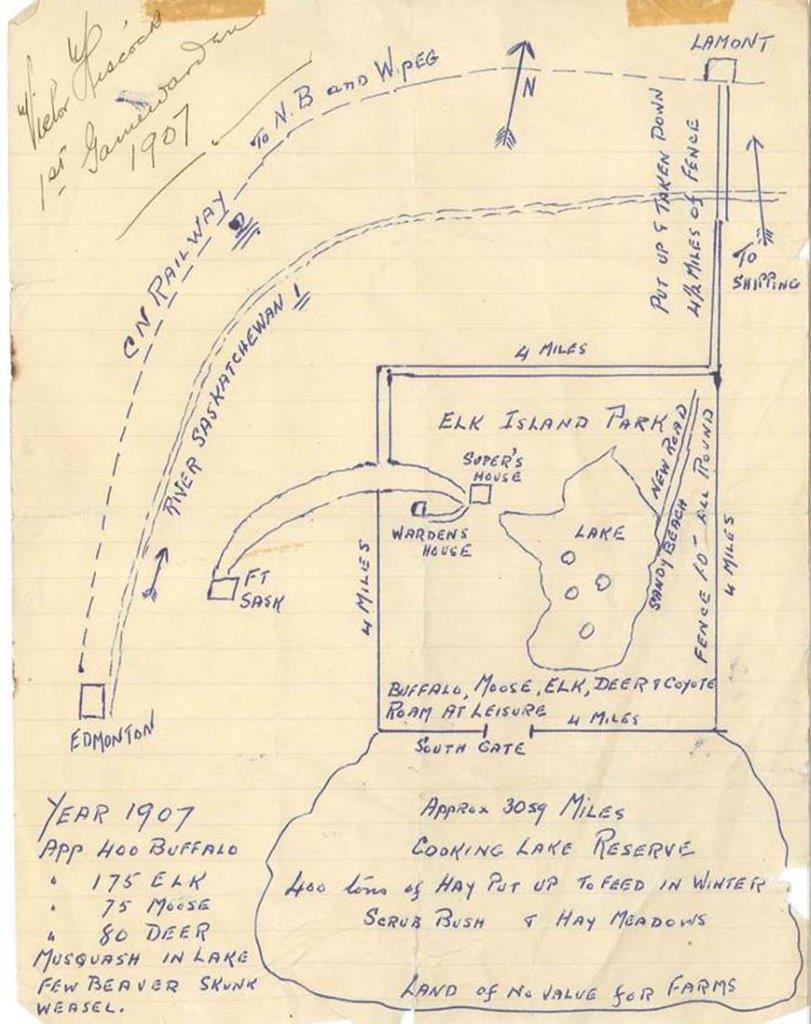

By the end of 1907 Elk Island was stocked with 400 buffalo, 175 elk, 75 moose and 80 deer, according to its first Game Warden Victor Hiscock.

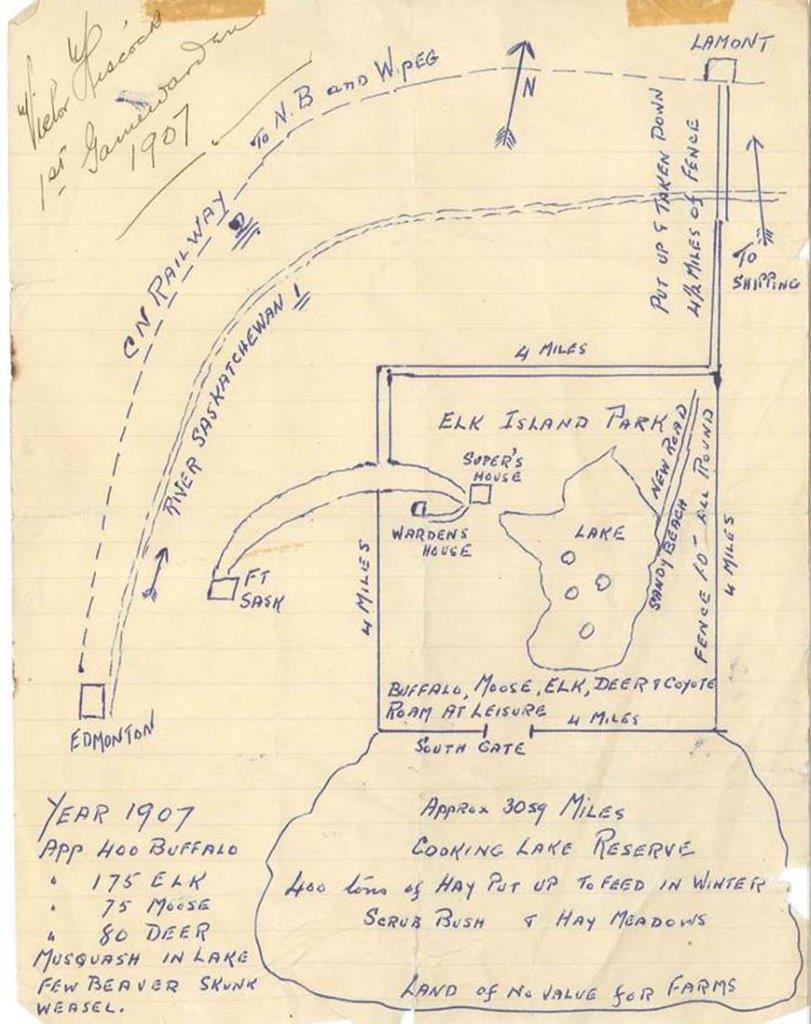

Hiscock sketched a map of Elk Island Park—the first destination for Pablo’s buffalo.

As seen in this map, signed by Hiscock in 1907, the Canadian National Railway swung a quarter circle to the Lamont Station, seen at the top right, following the Saskatchewan River from Edmonton, at the lower left.

This is Game Warden Victor Hiscock’s map of the first destination for Pablo’s buffalo at Elk Island Park. They were unloaded at Lamont Station and trailed 4½ miles into the Park.

At Lamont Station the buffalo were unloaded and trailed 4 ½ miles along a temporary fence. Most likely, this was built as a temporary trail fenced on both sides, bringing the wild herds running across the river and through a gate into Elk Island Park.

On the map Elk Island Park appears to be 16 square miles, 4 miles on each side, surrounded by 10-foot fences. Since Hiscock noted the size at approximately 30 square miles, the park probably included hay meadows, where 400 tons of hay were stacked for winter feed for the elk and buffalo.

In addition to the lake containing small islands—hence the name Elk Island—the park area included a warden’s house and what was identified as Fort Sask (Ft. Saskatchewan).

Within this area Hiscock listed 400 buffalo, 175 elk, 75 moose and 80 deer. In addition, he noted there were musquask (muskrats?), a few beaver, skunk, weasel and coyotes, which “roam at leisure.”

It was a perfect halfway station for Pablo’s buffalo.

Canadians Praise Pablo—Man of ‘Sterling Integrity’

In Canada, Michel Pablo was praised as a man of “sterling integrity” who kept his promises.

He received offers from individuals in the United States to sell his remaining bison at even higher prices than agreed-upon with Canada. But Pablo remained steadfast in his agreement with the Canadians.

One D.J. Benham, a journalist for the Edmonton Bulletin in Canada, wrote in Nov 8, 1907:

“When the sale to a foreign country was positively confirmed it aroused a storm of opposition and criticism, especially in Montana, where it was looked upon as a distinct national loss.

“Offers of double and nearly treble the price Canada was paying were officially made to Mr. Pablo, presumably with the hope that the great monetary consideration of nearly a quarter of a million dollars might be an inducement sufficiently alluring to cause him to break his bargain. . .

“[But] Mr. Pablo. . . is a gentleman of sterling integrity, one whose word is bond. It stands greatly to his credit that all the alluring offers for his buffalo, even one of $700 a head, were quietly refused on the ground that a bargain is a bargain and as such is sacred.

“He belongs to the ranching period and is a striking example of what a man of determination may accomplish in achieving success in the face of adverse circumstances sufficient to discourage the majority.

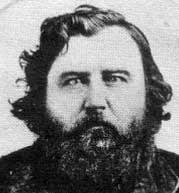

“Of magnificent physique bred by a strenuous life in the open, tall and still erect he carries his 68 years so lightly that he might easily be mistaken for a man of 50.

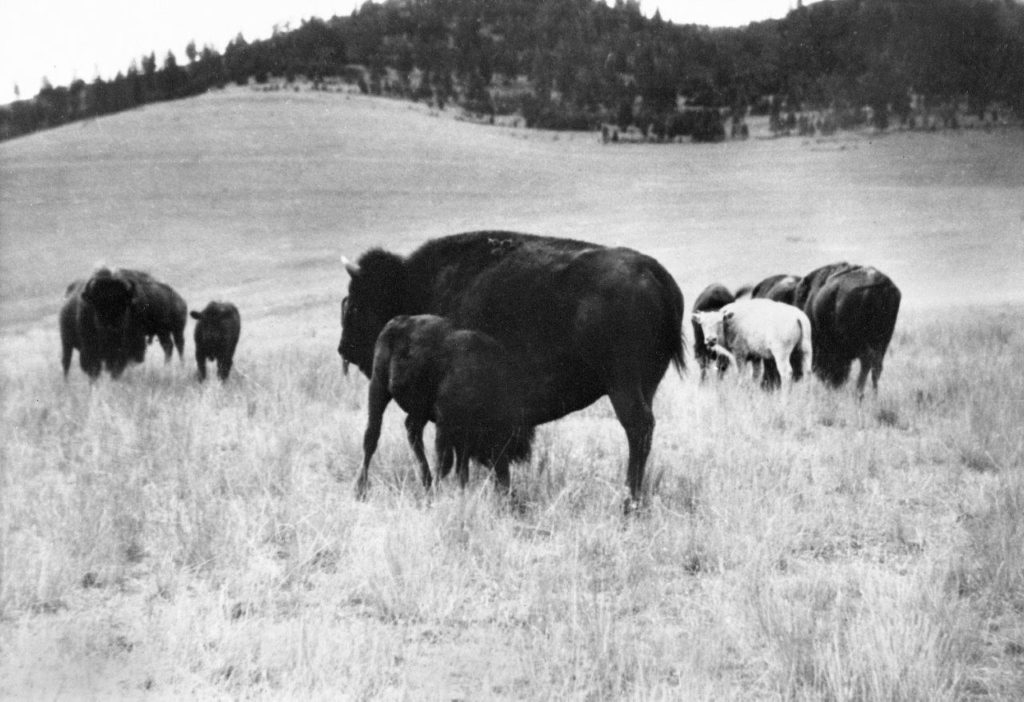

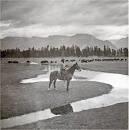

Michel Pablo surveying his herd of buffalo on his Montana ranch. The Canadian press praised Pablo as a leader and man of honor. A man of “magnificent physique bred by a strenuous life in the open, tall and still erect he carries his 68 years so lightly that he might easily be mistaken for a man of 50.”

“Quiet determination is stamped on his features, while his other dominant characteristics would single him out as a leader in any community. He had resolutely made up his mind that Canada . . . should reap the reward of enterprise and straightforward dealing.

“Among those who know him best Mr. Pablo is regarded as the soul of honour and he enjoys their esteem accordingly.”

‘The finest herd of American Bison in the world’

William Hornaday, president of the newly formed American Bison Society, wrote his congratulations to the Canadians in that organization’s annual report:

“The most important event of 1907 in the life history of the American Bison was the action of the Canadian Government in purchasing the entire Pablo-Allard herd of 628 animals, and transporting 398 of them to Elk Island Park, Canada.

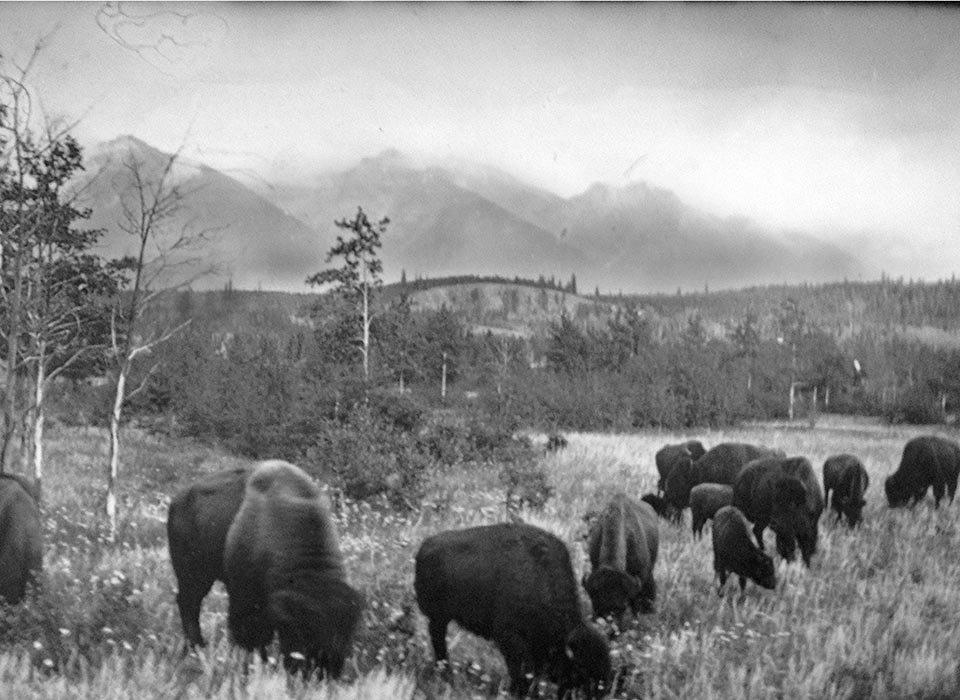

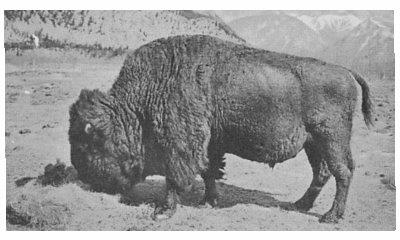

“A fine pair in the world’s finest herd,” photographer NA Foster titled this photo of Pablo’s buffalo in Montana, with the snow-capped Mission Mountains in the background. Montana Historical Society.

“Of the 240 Bison still remaining on the Flathead range, all save 10 head belong to Canada, and will be removed during 1908.

“Inasmuch as it was impossible to induce the United States Government to purchase the Pablo-Allard herd, and forever maintain it on the Flathead Reservation, the next best thing was that it should pass into the hands of the Canadian Government, and be located on the upper half of the former range of the species.

“The Canadian Government deserves to be sincerely congratulated upon its wisdom, its foresight and its genuine enterprise in providing $157,000 for the purchase of the Pablo herd, in addition to the cost of transporting the animals, and fencing Elk Island Park.

“It is for the Canadians to write the full history of this important transaction, and record the names of the men who are entitled to the credit for the grand coup by which Canada secured for her people the finest herd of American Bison in the world.

“The friends of the Bison may indeed be thankful that the great northwestern herd is not to be scattered to the ends of the earth, and finally disappear in the unstable hands of private individuals.

“The Pablo herd should not have been permitted to leave the country. . . But Pablo cannot be blamed for the sale. The expense to Pablo has been great.

“The reservation is soon to be thrown open, his range will be gone, and so large a herd cannot be maintained without a large and free range. It is said on excellent authority he would prefer to have them kept in America, but saw no opportunity to sell to the Government.”

When the decision was finally made by the US Congress to establish a National Bison Range in the Flathead Valley, under the continual urging of the newly formed American Bison Society and its members, Hornaday made this comment.

“The cost of the [Flathead] range will not be as great as the loss to the nation of the herd that has been sold.

“If the money that should have been put into the herd is now in part put into this range, and in part into animals, in a few years the increment will be such as to make a herd of which the nation may be proud.”

Origins of Pablo’s Buffalo

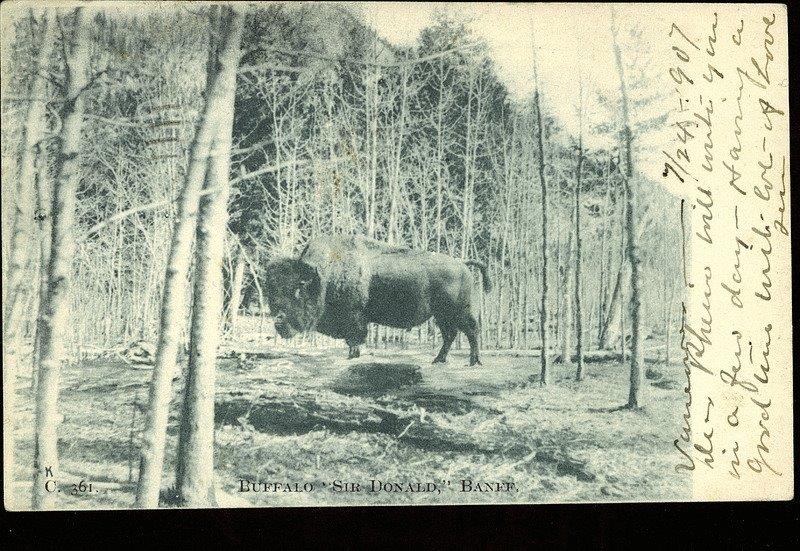

Although Canada’s first public buffalo herd was the small exhibition herd in Banff originating with James McKay, the bulk of the plains bison in Canada today came not from Banff, but from a single source: the Pablo-Allard herd.

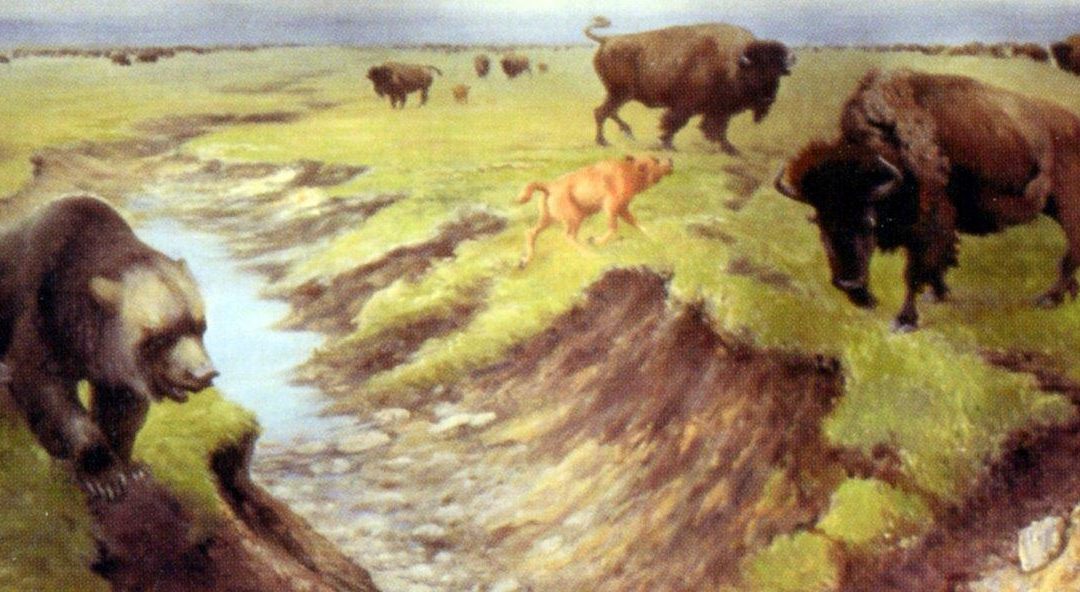

Pablo’s buffalo were a grand genetic mix of buffalo that originated from calves captured in both Canada and the United States, by Sam Walking Coyote, James McKay, Charles Goodnight and Buffalo Jones, as far distant as Saskatchewan, Montana, Kansas and Texas.

While Jones had captured some bison in Kansas and Texas, some of his bison were purchased from Samuel Bedson, and had been captured by James McKay in Saskatchewan.

With such different places of origin, the herd held by Pablo and Allard had genetic stock from across North America. These bison were kept cattle-gene free because the cattle-buffalo hybrids Pablo and Allard purchased from Jones, it was said, “were never allowed to mix with the thoroughbreds on the range, but were collected and sequestrated on Horse Island in the Flathead Lake.”

Pablo’s buffalo brought a grand genetic mix of buffalo that originated from calves captured in both Canada and the United States, from Saskatchewan, Montana, Kansas and Texas. Photographer Steve Edgerton, Parks Canada.

The herd’s origins with Sam Walking Coyote may have been small, but the plains bison gathered by Pablo and Allard were genetically diverse and all multiplied greatly.

15 Boxcars of Buffalo Arrive in July 1909

In Pablo’s third shipment in July 1909, 15 boxcars arrived in Canada loaded with 190 head of buffalo.

The Wainwright Star, Wainwright, Alberta, reported the welcome arrival of this impressive shipment on that day.

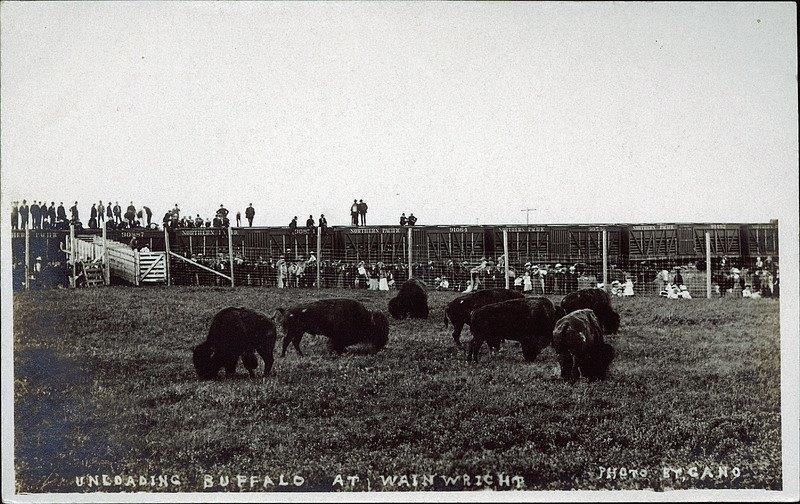

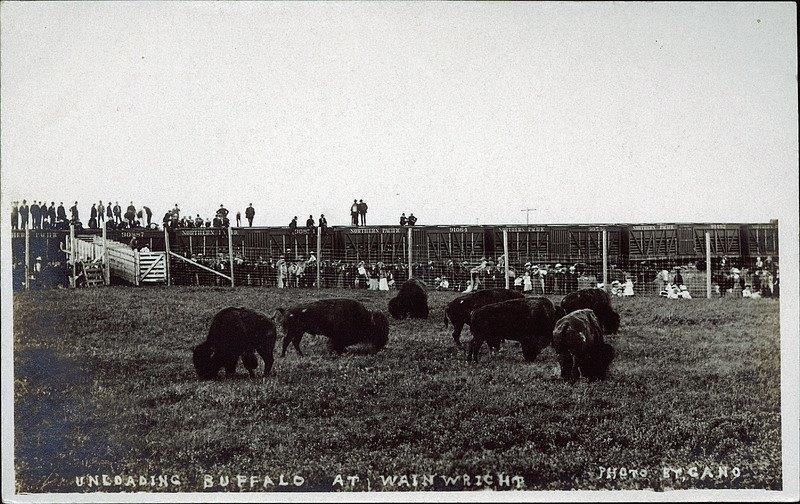

Unloading buffalo at the train station in Wainwright. Buffalo Trails and Tales, Wainwright and Districts.

“On Saturday last, 15 cars of buffalo arrived here from the Pablo herd in Montana, and were immediately unloaded in the Buffalo Park.

“The bunch consisted of 190 head and at times what seemed almost insurmountable obstacles have been overcome in rounding up this bunch.”

The July 1909 shipment unloaded at the new Buffalo National Park created near the town of Wainwright in east central Alberta on June 5, 1909.

Commissioner of Dominion Parks Howard Douglas, Montana Immigration Agent A. Ayotte, and H. C. McMullan, C. P. R. livestock agent, Calgary, accompanied the shipment.

“The animals comprising this shipment were immediately unloaded and despite expectations did not take unkindly to the fence around the corral at the unloading place.

“They had been in the cars for periods varying from 4 to 14 days and were consequently quite weary. The railway journey from Ravalli was made in the fine time of 72 hours and the bison stood the journey fairly well,” according to The Wainwright Star.

“No time was lost in releasing the buffalo, and before dark the entire trainload was quietly grazing in the park.

“Superintendent Ellis and his assistant, Louie Bioletti, gave every assistance to the party and we were enabled to see the buffalo at ease in their new home.

“They were scattered here and there in small herds, while an occasional one would be found enjoying a dust bath in one of the innumerable buffalo wallows, which were made by the wild herds many years ago.

“They seemed to take well to their new home and the majority paid scant attention to visitors.

They had been shut up in railway cars up to 14 days and were “weary,” but took well to their new home at Wainwright and paid scant attention to visitors.

“Occasionally, we ran across a small herd which viewed us with suspicion and started pawing the ground. When their tails began to raise with an ugly looking crook, we considered discretion to be the better part of valor and immediately left for other sections of the park.

“The 508 buffalo now in the park have an ideal home.” The Wainwright Star. Wainwright, Alberta, July 9, 1909.

Shipping ‘the Outlaw Remnant’

What was termed “the outlaw remnant” was still to be captured and shipped.

“There are still at least 150 head on the Flathead Reserve, which will be shipped in September. Before these arrive, however, 75 buffalo will be sent to the Park here from the Banff herd.”

In fact, after the July 1909 shipment the last 100 or so renegade buffalo arrived much more slowly than that, only a few at a time.

The renegade bulls were captured and shipped a few at a time.

The first three train shipments, two in 1907 and one in 1909, had brought 600 head to Elk Island.

Both Plains and Wood buffalo live in Elk Island National Park. Here two bulls spar off in testing their strength and resolve against each other. Parks Canada.

But after that the Canadian shipments dwindled fast, according to the American Bison Society’s annual report of March 31, 1913:

* 1st and 2nd shipments in 1907 – 410 head

* 3rd shipment July 1909 –190 head

* 4th shipment in October 1909 – 28 head

* 5th shipment June 1910 – 38 head

* 6th shipment October 1910 – 28 head

* 7th shipment May 2011 – 7 head

* 8th shipment – June 2012 – 7 head

Total from Michel Pablo was 708, according to that report.

Identified in the final shipment of 7 head were 1 two-year old bull, 3 cows, 2 yearling heifers and 1 calf.

“These animals were all in good condition on arrival,” reported Hornaday.

“It has been found necessary to slaughter some of the fierce old bulls which had been injured while fighting,” he added. “and the balance of these aged animals will later be transferred from their respective parks to Banff, where they will doubtless be a great attraction to tourists and others.”

After 1909, when the fences were completed, Pablo’s buffalo were shipped directly to the new Buffalo National Park near Wainwright.

Hornaday’s report lists the total buffalo at three Canadian National Parks—Elk Island, Wainwright and Banff–as 1,287 head by the end of 1913.

“The number of males is approximately the same as the number of females, and a large number of the former are aged. The total number of calves successfully raised during the year is 221.

“Several applications from city parks for live buffalo have been lately received and are under consideration, and one cow buffalo has been loaned to the City of Vancouver, BC, during the past season.”

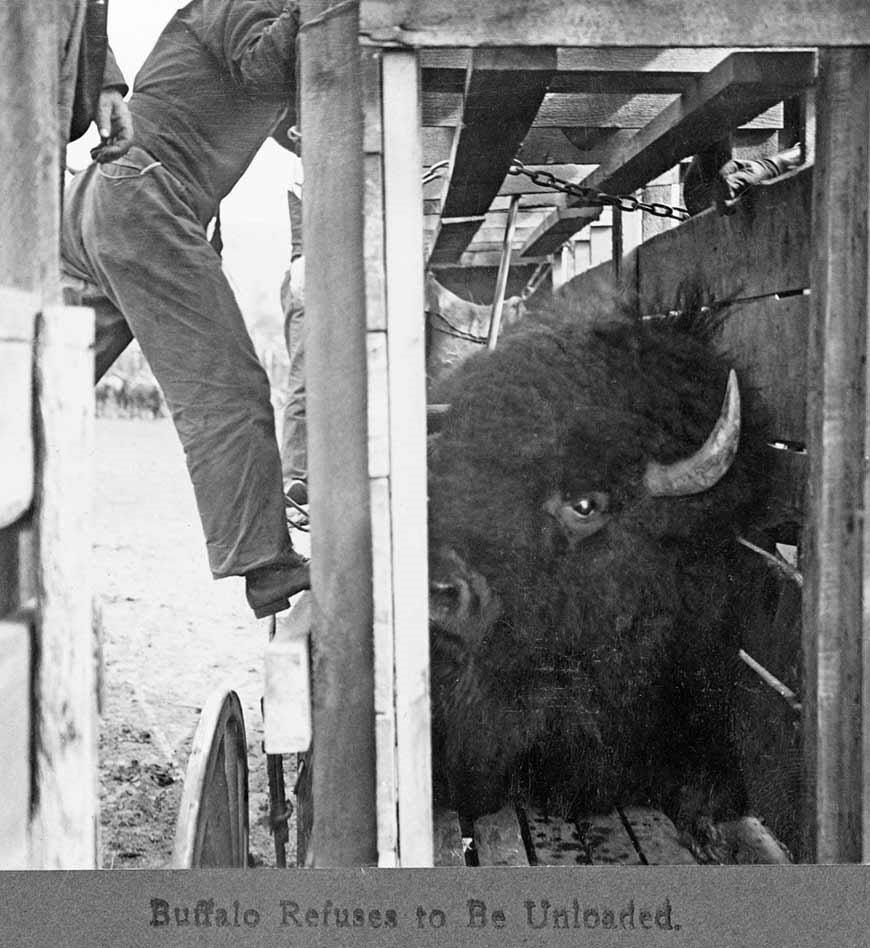

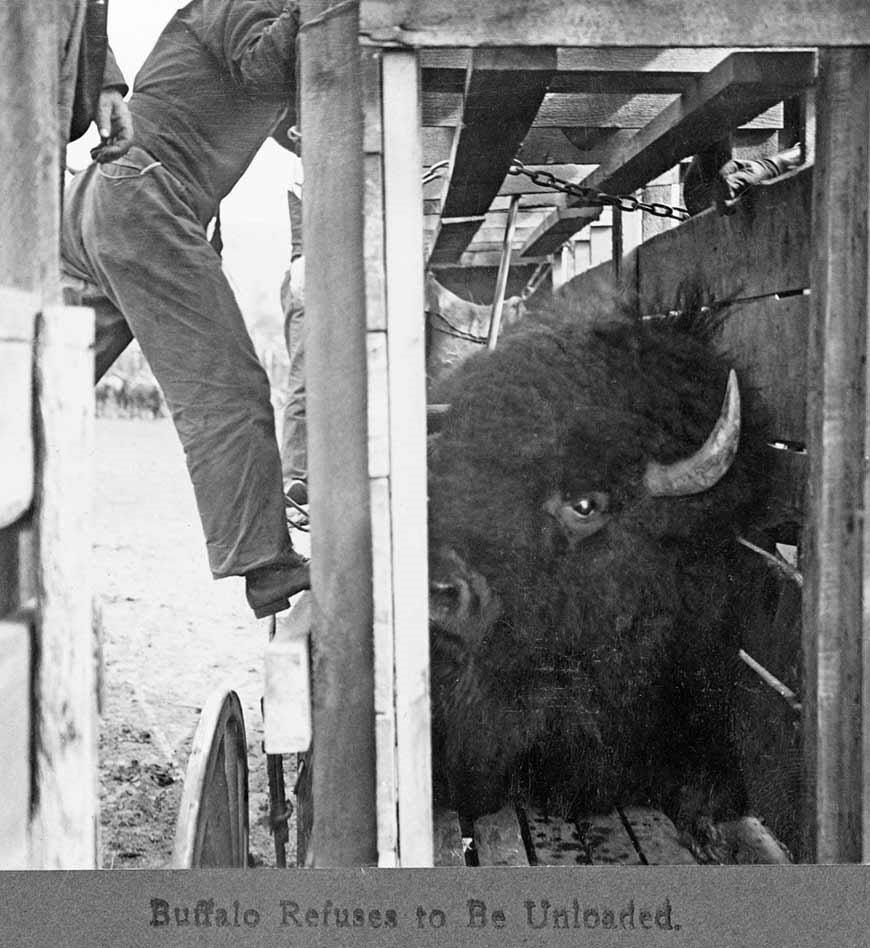

That “outlaw remnant” proved toughest of all to get loaded on rail cars.

An impassioned and sympathetic journalist in Missoula, FL Baghy, described their capture.

“Trapped into manmade corrals, roped and loaded into cages, bound down with chains and wire, hauled over long and rough roads, then dragged by main force Into freight cars and shipped like so many common cattle over the rail roads, nearly 600 of these lords of the plains have been dragged from the free and untrammeled range of their nativity into a national playground, where they will be kept as noble specimens of a rapidly vanishing species of American big game,”

“And when the 150 head that remain upon the reservation are rounded up and shipped this fall, there will be none of the noble animals left to dispute the right of the white man’s stock to- every blade of grass on the range where once the buffalo was lord of all he surveyed.”

But it was not that easy. These were wild bison. The 150 were the wiliest and most troublesome of wild buffalo. They had escaped many times from the skilled cowboys Pablo hired.

Reporters observed that many horses were killed and many cowboys injured. Finally fences 26 miles long, converging to the corrals at Ravalli, Montana, were built, and the wildest and fiercest of all bison were gradually brought together in small bands.

Often when they found themselves being driven from their native hideouts, they turned on the cowboys.

Exhibition Herd Maintained at Elk Island

The bison were only supposed to be at Elk Island Park temporarily but they quickly became a main attraction. The park was just east of Edmonton on the open Plains.

From the time of their arrival, they caused a sensation among local people and visitors from across Canada. There’d been no buffalo in the Edmonton area for more than 30 years and thousands of people marveled at these “Majestic Monarchs of the Plains.”

In 1909 the fences of the new Buffalo National Park near Wainwright were completed, so the bison at Elk Island were rounded up and shipped to the new park.

But the Minister of the Interior, Edmontonian Frank Oliver, ordered a small exhibition herd left behind.

Lone bull grazes at Elk Island National Park. Parks Canada.

It was the 40 to 70 who evaded capture that formed the nucleus of the bison at Elk Island today—a herd that would grow over the years and see individuals sent to support numerous conservation herds around the world.

It is a good thing, say Park managers today, that these bison remained at Elk Island, because things did not go well for Buffalo National Park at Wainwright.

A Tough Workout for Buffalo Wranglers

For the second roundup in November that fall, the Canadian press—waiting in the wings—had this to say:

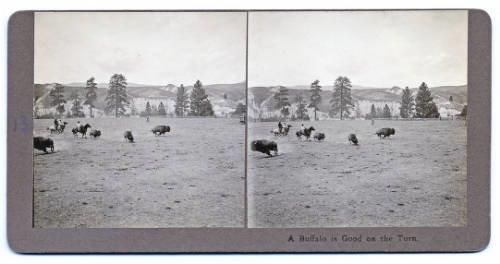

“The drives . . . were as spectacular as anything ever seen on the range.

“The battle grounds were in the bad lands of Pend d’Oreille and in the foothills of the mountains, where every man took his life in his hands in the dare-devil dashes hither and thither, through cuts and ravines, over ridges and foothills or down the valleys honeycombed by the dry courses of the mountain torrents, in fast and furious pursuit of the bands of buffalo. . .”

“Sometimes the cowboys were the pursuers and sometimes they were pursued.

“In cases where their anxiety to turn an animal carried them closer to the buffalo than discretion should warrant, a vicious charge would result, and the rider would have to extend his horse to the limit to escape from the horns of the furious monster.”

The Winnipeg Tribune, Dec 22, 1922, commented on the last shipment (which netted only 7 head):

In capturing the last “outlaw remnant,” the Canadian Press noted, “Sometimes the cowboys were the pursuers and sometimes they were pursued.” Photo by Steve Edgerton, Parks Canada.

“Only three times in six weeks of daily drives did the cowboys succeed in getting any of the buffalo into the corrals.

“The buffalo, when they found themselves being driven from their native pastures, turned on the cowboys. Many horses were killed and many cowboys injured.

“Finally fences 26 miles long, converging to the corrals at Ravalli, were built and the buffalo were gradually brought together.

Making a Last Fierce Struggle for Freedom. Often when a buffalo went down in the chute, he simply gave up and died. Courtesy Montana Historical Society.

“From Ravalli they traveled by railway to the reserve provided for them near Wainwright, where they have increased and multiplied, until they now number some 7,000.”

Montana’s Daily Missoulian had explained the difficulties of Pablo’s first roundup on May 29, 1907. The reporter warned, “To get a good idea of the difficulties that attend this work, take the most ornery range steer, multiply his meanness by 10, his stubbornness by 15, his strength by 40, his endurance by 50 and then add the products. You will then have some conception of the patience and skill that are required to load buffalo into a stock car.”

The total of 708 head in the American Bison Society count were far more than the Canadian Government thought they were going to receive. Some were young calves and apparently, each animal was counted separately and paid for in full regardless of age, including newborn calves, so the numbers kept changing in various reports.

According to the modern Canadian scientist Valerius Geist, during the 6 years between June 1, 1907 and June 6, 1912, Pablo delivered to Canadian authorities 716 bison. Of these, 631 went to Buffalo National Park and the other 85, to Elk Island National Park.

They were healthy and fertile, continually multiplying. The Canadian information written in the American Bison Society annual report indicated there were about 1,006 buffalo in National Parks distributed as follows: 27 head in Banff, 61 at Elk Island Park and 918 in Buffalo Park.

By 1919 between the three sites—Buffalo Park, Elk Island, and Banff—Canada’s National Park system owned 4,033 bison, in both the Plains and Wood buffalo subspecies.

Canadian rangers did a great deal of shifting these buffalo around as the years went by, and the prolific herds doubled and redoubled their numbers everywhere they were placed.

Corrals were built near the river to load buffalo onto boats for shipping to their various parks and destinations across Canada. Parks Canada.

For example, in June 1925 some 6,673 plains bison were shipped from Buffalo National Park to Wood Buffalo National Park. This included 4,826 yearlings, 1,515 two-year-olds, and 332 three-year-olds, most of them female.