Red River Carts emerged from every nook and corner of Fort Garry bound for Pembina and the western plains. It was 1840 and the Métis of course had horses and guns for their buffalo hunts. Their roots went back to Indian mothers, and fur trading fathers or grandfathers from France, England or Scotland.

“Carts were seen to emerge from every nook and corner of the settlement bound for the plains … From Fort Garry, the cavalcade and camp-followers went crowding on to the public road, and thence, stretching from point to point, till the third day in the evening, when they reached Pembina, the great rendezvous on such occasions.

“Here the roll was called and general muster taken, when they numbered on this occasion, 1,630 souls; and here the rules and regulations for the journey were finally settled. The officials for the trip were named and installed into office—and all without the aid of writing materials.

“The camp occupied as much ground as a modern city and was formed in a circle. The carts were placed side by side, the trains or cart tongues facing out-ward.

“These are trifles, yet they are important to our subject. Within this line of circumvallation, the tents were placed in double, treble rows, at one end; the animals at the other in front of the tents.

“This is in order in all dangerous places. But where no danger is apprehended, the animals are kept on the outside. Thus the carts formed a strong barrier, not only for securing the people and their animals within, but as a place of shelter against an attack of the enemy without.”

As described by Alexander Ross, a Scotch fur trader, the Métis from along the Red River of the North were gathering in Pembina, North Dakota, for their annual summer buffalo hunt.

It was June 15, 1840, as their cart caravan prepared to take off west for the open Plains.

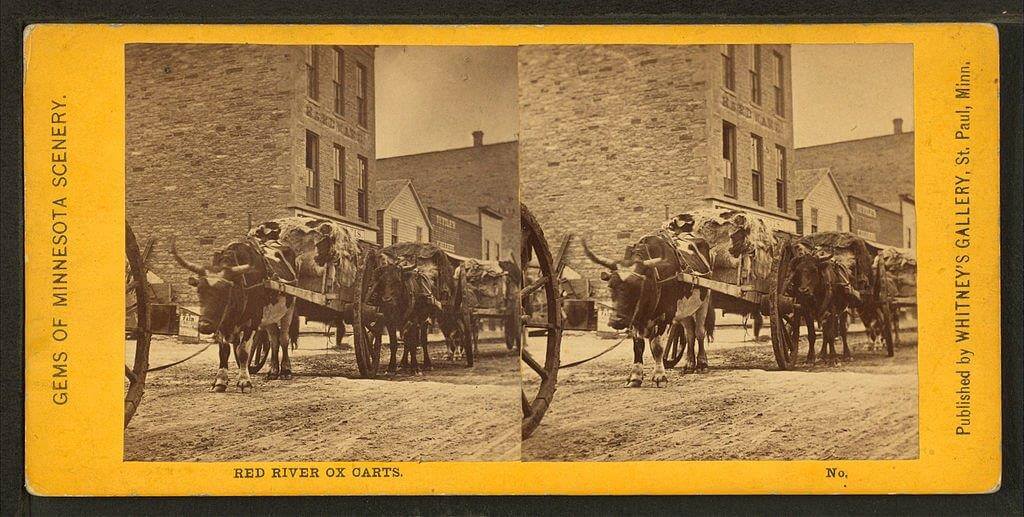

These carts were not just ordinary wagons. They were known as Red River Carts. Built in the style of French peasant carts with two over-size wooden wheels, large enough to smooth out the ride over rough terrain and bound with leather straps.

The wooden wheels were not greased because the prairie dust would stick to the oil and clog up the wheels.

On the buffalo hunt each family took several carts pulled by an ox or horse to fill with hides and meat. The loud screeching noise of the ungreased wheels could be heard for miles. Women and small children rode on top of the load.

From the beginning Red River Métis had horses and guns for their buffalo hunts. Their roots went back to Indian mothers—mostly Cree, Ojibwe, Chippewa and Assiniboin. Mothers held long traditions in buffalo hunting and care of the meat.

The fathers or grandfathers were French, Scotch or English. Explorers and fur traders who paddled their canoes up the western rivers in the 1700s and early 1800s and settled with their families along the Red River on both sides of the Canadian-US border.

In French style they farmed small plots of land fronting on the river, which flows north into Hudson Bay—long a fur trader’s route to European points.

The Red River Métis built log cabins along the Red River, which flows north to Ft. Gerry and thence into Hudson Bay. On these fertile lands they grew Indian corn, wheat, barley, potatoes and vegetables. Twice yearly they went west on the open plains for Buffalo Hunts as well as engaging in hunting and trapping at home.

The fathers provided horses and guns. Mothers contributed traditional buffalo hunting culture. They ran buffalo in traditional Native American ways, according to historic accounts.

The Métis—pronounced Mah tee’ or Mah tees’ developed a strong market for jerky and pemmican with the fur trade and made a wholesale commercial business of hunting buffalo.

They launched two big buffalo hunts a year, a two-month summer hunt in mid-June after planting crops, and a fall hunt when buffalo were fat and their hides prime for curing with the hair on.

During these hunts they swept westward into Alberta and Saskatchewan and southwest into the Great Plains of Montana and the Dakotas

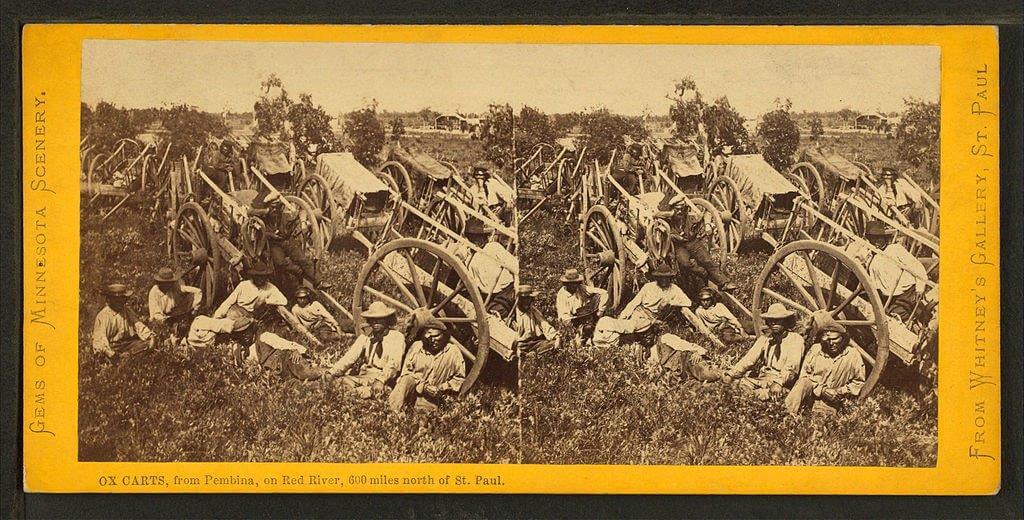

Red River Carts were parked at night on one side of the circle with wagon tongues facing out to offer protection from attack. In areas of risk, animals were kept inside the circle overnight. Credit Whitney’s Gallerty, St. Paul.

As early as 1823 William H. Keating described a colorful group of Métis buffalo hunters who came from Fort Garry to rendezvous at Pembina, south of the border, waiting for others to arrive.

That year 300 people came together to hunt in the Dakota plains and prairies, with at least 200 horses and 115 Red River carts. A fun-loving people, they filled their evenings with dancing and fiddle playing.

The Métis hunts were known by their long caravans of Red River carts crossing the prairies bound for the buffalo ranges and then, loaded with hides and pemmican, travelling to markets in Ft. Garry and St. Paul, Minn.

Their religion was Catholic and their language a patois of French, Chippewa, Cree and other Indian tongues. The Métis brought their priests along on the hunts, held Sunday services and did not hunt or travel on that day.

Women packed extensive provisions for buffalo hunts, cooked, cared for babies and drove oxcarts. Often they left younger children to be cared for by others at home.

Women wore calico dresses with long, full skirts. Skilled at beadwork, they decorated moccasins for men, women and children and other leatherwork in distinctive bright French floral designs.

For winter buffalo hunts, Métis men wore woolen pants, calico shirts and a Hudson Bay coat with hood attached, tied at the waist with a colorful sash. Moccasins and leather leggings were fastened around the leg by garters ornamented with beads and they slung their powder horn and shot bag over one shoulder.

The fur traders were French at first. They married or co-habited with Native women.

Their offspring at Red River became known as Métis—French for people of mixed blood.

Women played an important role in every buffalo hunt. From the first, European fur traders needed Native women to cook for them, to prepare food supplies for winter, make and repair clothing, moccasins and snowshoes, and heal them when sick or wounded.

In 1763 the British took over Canada. Then came English and Scottish fur traders.

Conflict with Sioux Hunting Parties

When hunting, the Red River Métis travelled in large groups for protection against plains tribes—especially the Sioux, who claimed hunting rights to the same territory and resented their wholesale slaughter of thousands of buffalo.

During the 1840s and 1850s the Métis followed the buffalo herds further into the Dakota Territory bringing them into conflict with the Sioux (Dakota). They might travel 200 miles or more west to find buffalo.

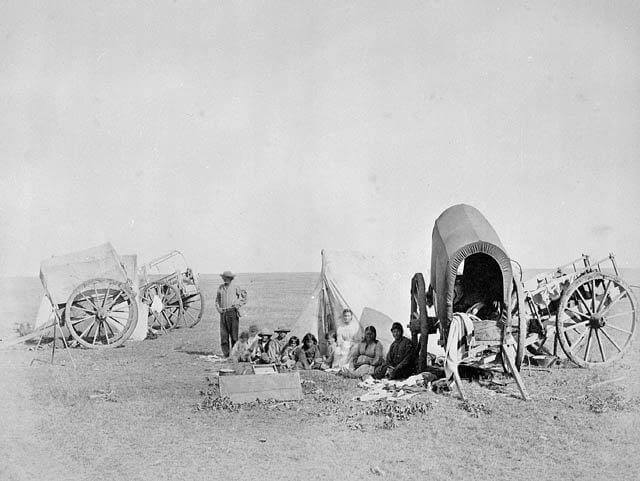

They set up their carts at night to form a solid defensive circle with forks facing out. Within the circle the tents were set up in rows on one side and, facing the tents, the animals on the other side. When deemed safe, the animals were kept outside the circle where they could graze.

Cuthbert Grant, an early captain of the buffalo hunt, negotiated a treaty with the Sioux in 1844, but it did not last.

In the 1848 summer hunt the hunting group, made up of 800 Métis led by Jean Baptiste Wilkie and 200 Chippewa led by Chief Old Red Bear and over 1,000 carts, met the Sioux in the Battle of O’Brien’s Coulée near Olga, North Dakota

Between July 13 and 14, 1851 a large band of Sioux attacked the St. François Xavier hunting camp in North Dakota on the Grand Coteau du Missouri resulting in the last major battle, the Battle of Grand Coteau, fought between the two groups.

The Métis were victorious. The Red River group from St. Boniface accompanied by Father Albert Lacombe, made rendezvous with the Pembina group (June 16) then travelled west to meet the St. François Xavier group (June 19).

There were 1,300 people, 1,100 carts and 318 hunters in the combined groups. The groups hunted separately but planned to unite against any threat from the Sioux. They divided into 3 groups about 20 to 30 miles from each other moving in the same direction.

The St. François Xavier from the White Horse Plains led by Jean Baptiste Falcon, son of Pierre Falcon, and accompanied by its missionary, Father Louis-François Richer Laflèche, numbered 200 carts and 67 hunters plus women and children.

Jean Baptiste Wilkie, the leader of the 1840, 1848 and the 1853 summer hunts, helped negotiate a peace treaty in 1859 and another in 1861 between the Métis, Chippewa and Sioux to set hunting boundary lines.

However, conflict continued between the Métis and various Sioux groups even after the Dakota War of 1862.

In North Dakota on the Grand Coteau of the Missouri in July, the scouts of St. François Xavier spotted a large band of Sioux. The five scouts riding back to warn the camp met with a party of 20 Sioux who surrounded them.

Two made a run for it under fire but 3 were kept as captives. Two escaped the next day and one killed. On Sunday July 13 the camp was attacked by the Sioux. Lafleche dressed only in a black cassock, white surplice and stole, directed with the camp commander Jean Baptiste Falcon a miraculous defense against the 2,000 Sioux combatants while holding up a crucifix during the battle.

After a siege of two days the Sioux withdrew, convinced that the Great Spirit had protected the Métis.

Red River Métis Buffalo Hunting

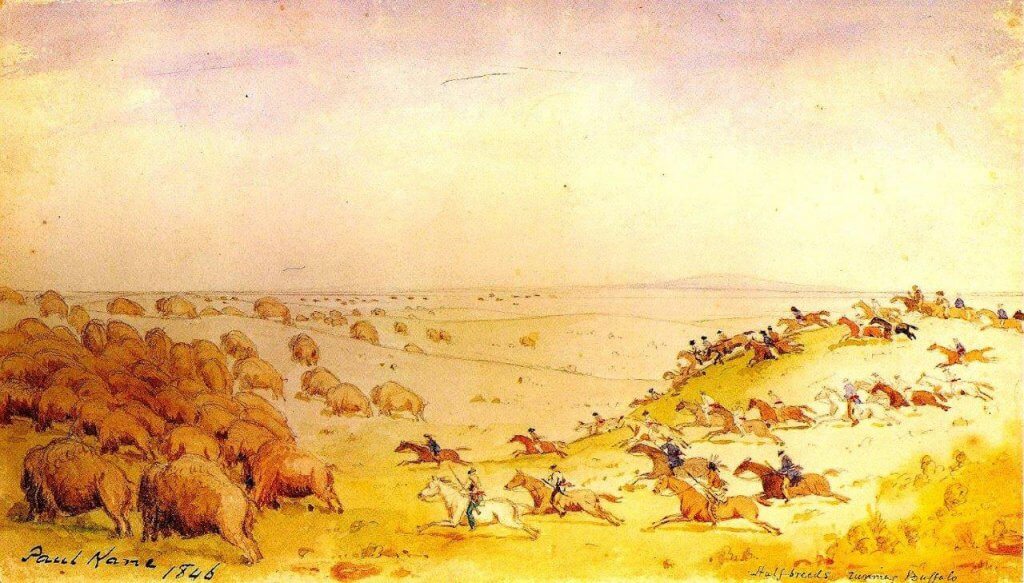

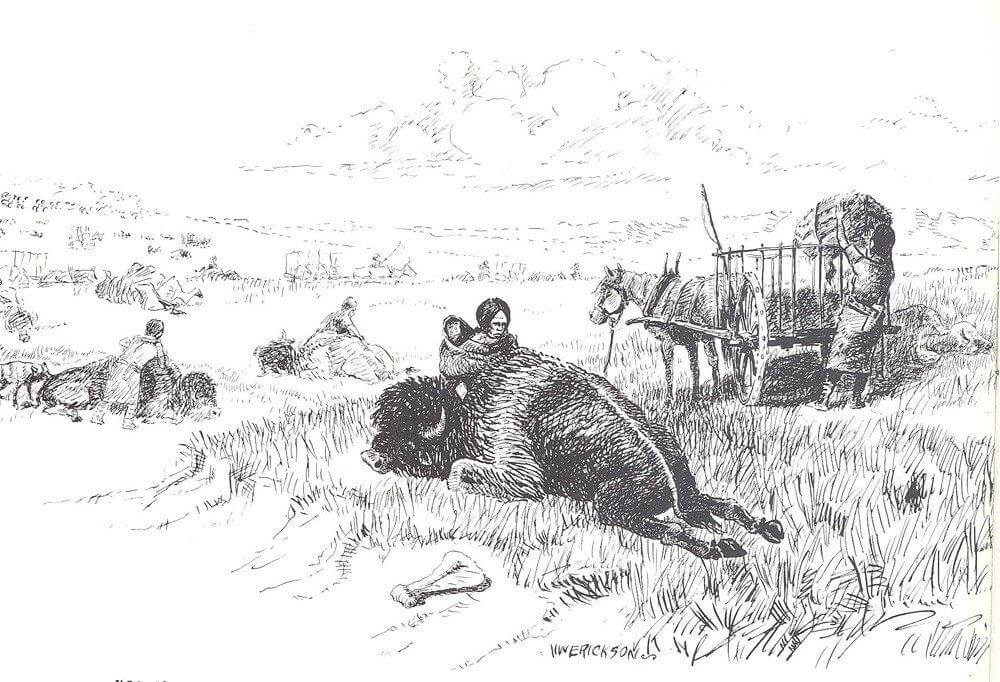

Buffalo hunting. “A superior sport, manly, exhilarating and well spiced with danger. Even the horses shared the excitement and eagerness of their riders. It . . . demanded a good horse, a bold rider, a firm seat and perfect familiarity with weapons. The excitement of it was intense, the dangers not to be despised and, above all, the buffalo had a fair show for his life, or partially so, at least.” Painting of Métis hunt, credit Paul Kane, 1846.

When hunting, the Red River Métis organized into camps and followed rules that were strictly enforced so no one would scare the buffalo away before everyone was ready. When the signal was given, hundreds of men raced towards the buffalo.

Each marked the buffalo he shot. At the end of the day, exhausted hunters ate, rested and related details of the hunt. Women and children set to work caring for meat and stretching and pegging down hides.

The Red River Métis were excellent riders and marksmen. They raised horses for the buffalo hunt and oxen for farm work and hauling the Red River carts loaded with buffalo pelts for St Paul.

The Red River Métis buffalo hunts described by observers were of the traditional Native American buffalo running style.

Leaders of the hunts laid careful plans. Throughout, the people integrated devout religious fervor, ceremony and ancient tradition in their preparations and in the activities of the hunt. They thanked the buffalo, their relatives, for providing them with meat and many more gifts before, during and after the hunt.

Even William Hornaday, in his sober assessment, called running buffalo “A superior sport.” He wrote that it was “manly, exhilarating and well spiced with danger. Even the horses shared the excitement and eagerness of their riders.

“It …demanded a good horse, a bold rider, a firm seat and perfect familiarity with weapons. The excitement of it was intense, the dangers not to be despised and, above all, the buffalo had a fair show for his life, or partially so, at least.”

Scouts—usually young men—were selected. They rode out for several days and if they located a sizeable herd of buffalo, signaled their discovery from ten miles off, later on riding into camp and giving a careful report according to traditional ways.

The mounted hunters stealthily approached the herd from both sides.

Then, following strict orders to start at the same moment—on threat of severe punishment—at the leader’s signal the hunters swept down on their game. They loaded and fired from horseback, leaving the dead animals to be identified after the run was over.

Indian horses seemed to take special pleasure in running buffalo. Their excitement in running buffalo is described this way by an observer:

“But for the willingness and even genuine eagerness with which the buffalo horses entered into the chase, hunting on horseback would have been attended with almost insurmountable difficulties.”

The Hon. H. H. Sibley told of the dedication of one horse that had lost its rider on a Red River Métis hunt.

“One of the hunters fell from his saddle and was unable to overtake his horse, which continued the chase as if he of himself could accomplish great things, so much do these animals become imbued with a passion for this sport!”

Another hunter left his favorite buffalo horse in camp for a day’s rest, asking his wife to tie the horse. But the horse pulled loose and galloped off to join the hunt.

“He continued to keep pace with the hunters in their pursuit of the buffalo, seeming to await with impatience the fall of some of them to earth. The chase ended. He came neighing to his master, whom he soon singled out, although the men were dispersed here and there for a distance of miles,” wrote Sibley.

Métis familes stop for lunch, perhaps awaiting outcome of the latest hunt.

Red River Métis Buffalo Hunts—1840, 1849 and 1853

The first of the summer hunting expedition left Fort Garry on June 15, 1840.

In three days they reached their rendezvous at Pembina, ND, 60 miles to the south, and set up a tent city. At Pembina a general council was held and leaders chosen.

There were 620 hunters, 650 women and 360 boys and girls–1,630 people all together. They brought with them 1,210 Red River carts, 403 buffalo runners (horses), 655 cart horses, 586 work oxen and 542 dogs.

Ten captains were selected, Jean Baptiste Wilkie was chosen as the war chief and the president of the camp. Each captain had ten soldiers under him. Ten guides were also chosen. A smaller council of the leaders was also held to lay down the rules or laws of the hunt.

Rules for the Métis Hunt

The following rules were made by the Red River Metis for the 1840 hunt.

- No buffalo to be run on the Sabbath Day.

- No party to fork off, lag behind, or go before, without permission.

- No person or party to run buffalo before the general order.

- Every captain with his men, in turn, to patrol the camp, and keep guard.

- For the first trespass against these laws, the offender to have his saddle and bridle cut up.

- For the second offence, the coat to be taken off the offender’s back, and be cut up.

- For the third offence, the offender to be flogged.

- Any person convicted of theft, even to the value of a sinew, to be brought to the middle of the camp, and the crier to call out his or her name three times, adding the word “Thief,” at each time.

Leaving Pembina on June 21 the group travelled 150 miles southwest, reaching the Sheyenne River nine days later.

On July 3, sighting buffalo 100 miles further, 400 mounted hunters killed about 1,000.

The women then arrived in carts to cut up the meat and haul it back to camp. It took them several days to dry and store the dried meat.

The camp then moved on to another site. That year the hunting group returned to Fort Garry with about 900 pounds of buffalo meat per cart or 1,089,000 pounds in all—or the dried meat of between 10,000 to 10,500 buffalo.

In 1849 there were two summer hunts from the Red River. The St. Francois Xavier—White Horse Plain group—alone numbered 700 Métis, 200 Indians, 603 carts, 600 horses, 200 oxen and 400 dogs.

Isaac Stevens of the US Pacific Railroad Surveys, who camped near the Red River hunters near Devil’s Lake, ND, on July 16, 1853 provided this description of the 1853 summer hunt:

“The hunt was led by Jean Baptiste Wilkie and had 1,300 people, 1,200 animals and 824 carts. The camp consisted of 104 tepees, most shared by two families, arranged within a circle of carts which, covered in skins, provided additional sleeping quarters.

“The animals are driven into the circle at night and 36 men stand guard on the sleeping camp.

“They are generally accompanied by their priests, and attend strictly to their devotions, having exercises every Sabbath, on which day they neither march nor hunt.

“Their municipal government is of a parochial character, being divided into five parishes, each one being presided over by an officer called the captain of the parish. These captains of the parish retain their authority while in the settlement.

“On departing for the hunt they select a man from the whole number, who is styled governor of the hunt, who takes charge of the party, regulates its movement, acts as referee in all cases where any differences arise between the members in regard to game or other matters, and takes command in case of difficulty with the Indians,” according to Stevens.

Six days later Stevens encountered another Métis hunting group led by Urbain Delorme of St. Francois Xavier. Delorme’s group averaged 500 carts for 25 consecutive years, it was said.

Accidents and Endurance

Running buffalo at close range was extremely dangerous. Often the hunter found himself hemmed in by the stampeding herd, in clouds of dust, so that neither he nor his horse could see the terrain beneath them. Fatal accidents to both men and horses were numerous.

Alexander Ross described a hunt by 400 Métis hunters from the Red River settlement. “The surface was rocky and full of badger holes. Twenty-three horses and riders were at one moment all sprawling on the ground.

“One horse, gored by a bull, was killed on the spot. Two more were disabled by the fall. One rider broke his shoulder blade. Another burst his gun and lost three fingers. And a third was struck on the knee by an exhausted ball.”

But the rewards were perhaps worth it, he wrote. “These accidents will not be thought over-numerous, considering the result. For in the evening no less than 1,375 tongues were brought into camp.”

Your content goes here. Edit or remove this text inline or in the module Content settings. You can also style every aspect of this content in the module Design settings and even apply custom CSS to this text in the module Advanced settings.

After the kill, women arrived in carts to cut up the meat and haul it back to camp. They laid claim to their man’s buffalo from his mark or item of clothing left with it. It took several days to dry and prepare the dried meat.

After every buffalo kill, the women cut up the meat brought in and began the process of drying meat to make jerky and pemmican—the chief food product used in the far flung fur trade.

Pemmican—Staple Food for Fur Traders

They made pemmican by pounding the dried meat into pieces, placing it into an oblong bag of buffalo hide, and then pouring in an equal amount of hot buffalo fat. They mixed the contents thoroughly and sewed the bags shut. When available, crushed chokecherries or other berries were added.

Each bag weighed 90 to 100 pounds and held on average the carcass of one buffalo.

One cart could be loaded with ten of these bags or about 900 to 1,000 pounds of buffalo meat—the product of eight or ten cows. One pound of pemmican was considered equal in nutrition to four pounds of ordinary meat.

Thin sheets of buffalo meat were deftly sliced by unrolling chunks of meat as the women worked. Then the sheets were hung like rags to dry in the sun on a rack made of willow branches. Sometimes poles from dog or horse travois were propped up at the ends of the rack to stabilize it.

All the pemmican the Métis could spare was eagerly purchased by the Hudson Bay Company to send out to trading posts where food was scarce, especially after that company absorbed the North West Company.

Long lines of Red River Ox Carts loaded with buffalo hides and pemmican, products of the buffalo hunts, crossed the prairies of the Dakotas and Minnesota and arrived in St. Paul for sale. In exchange the families took home loads of blankets, cloth, sugar, coffee, tea and ammunition. Credit Whitney’s Gallery.

The summer hunts increased in size—from 540 Red River carts in 1820, to 820 carts in 1830 and 1,210 carts in 1840—as the demand for pemmican kept growing. Hudson Bay and other fur companies depended on the products of their buffalo hunts well into the 1870s.

In 1823 Pembina was declared to be just south of the US border. In 1844 Norman Kittson opened a successful trading post at Pembina in competition with the Hudson’s Bay Company at Red River.

By 1849 the Hudson’s Bay Company had lost its fur trade monopoly (the result of the Sayer Trial) and the Métis could now freely sell their furs. As the price of buffalo robes increased so did the number of carts heading south from Pembina to St. Paul, Minnesota each year.

——

NEXT: Part 2. Métis Buffalo Hunting in the Far West

——

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog