How will you celebrate National Buffalo Day this year?

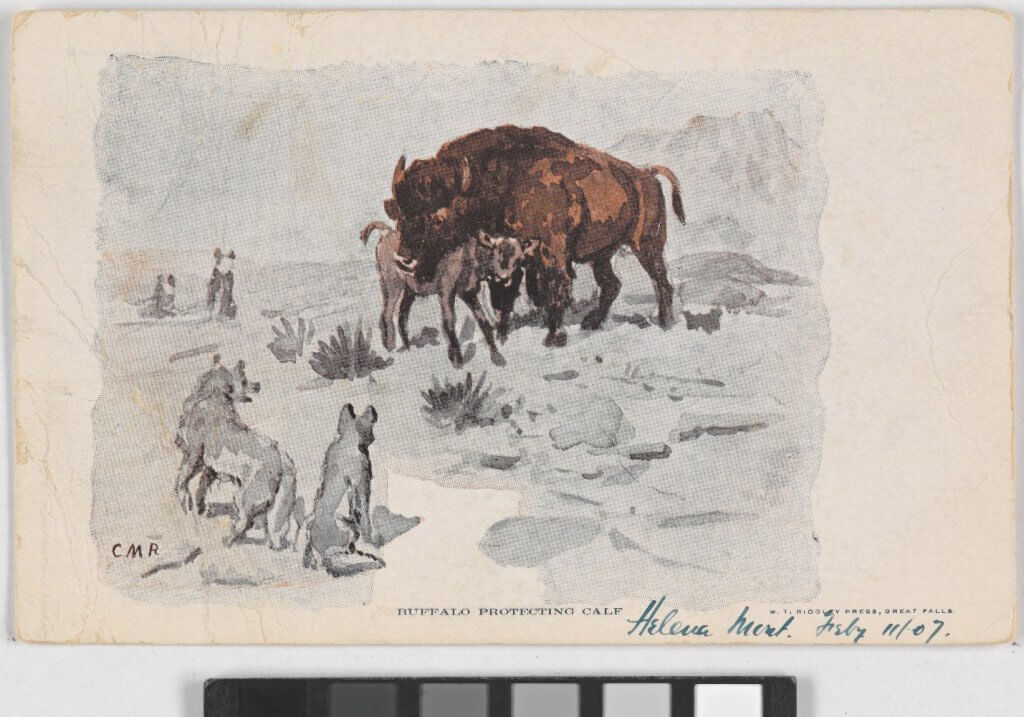

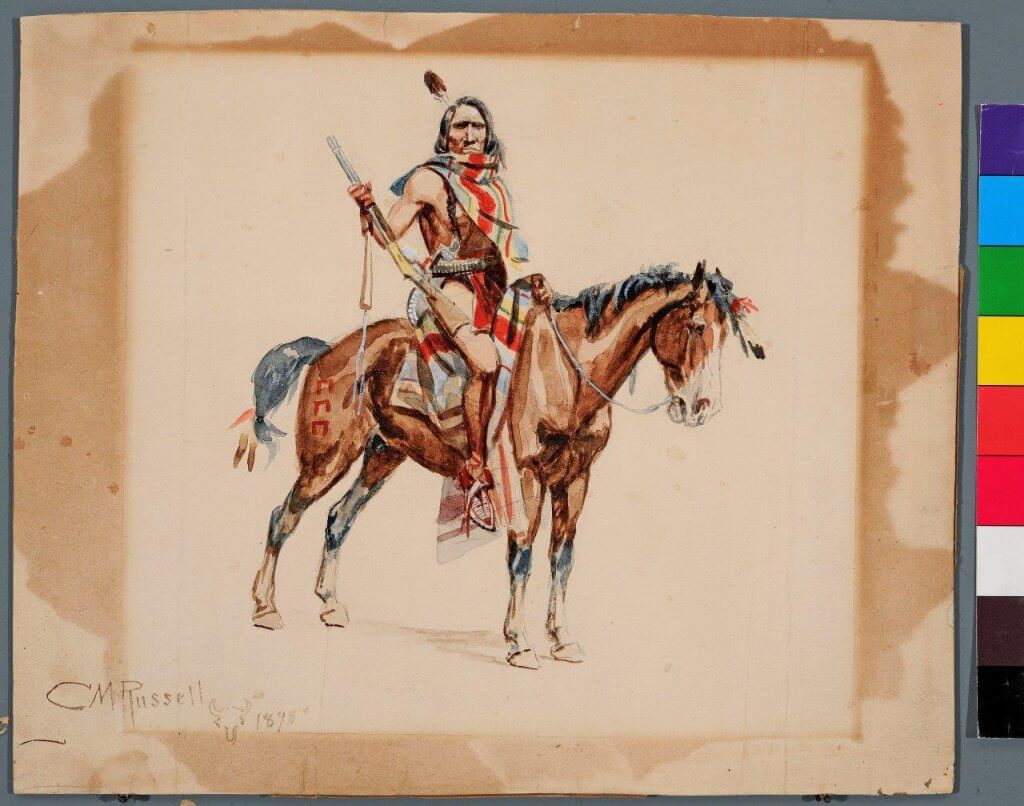

Protecting buffalo calves from wolves was—and today still is in certain areas—a major concern for the entire herd. Sketch by Charles M. Russell, Nov, 1907.

National Bison Day, November 6, 2021, is an annual event. It falls on the first Saturday in November each year. Americans are encouraged to reflect on the impact Bison have as a part of our environmental and cultural heritage.

Here’s a fun way for us to celebrate: Since we all love stories, why not honor this year’s National Buffalo Day by telling a favorite buffalo story?

Tell it several times—to your family, your buddies, a treasured friend in your long-time care home. Maybe at a meeting you happen to attend that day.

If you work with buffalo, I bet you have a personal, amazing or interesting story or two to share. Even second or third hand will be just fine.

If you’ll share them with us, we’ll reprint them here for National Buffalo Day. Please note the source and send them to us at: fmberg@ndsupernet.com

I’m starting early, so you might use these or zero in on your own.

Beginning in 2012, the movement grew to name the Bison as America’s national mammal to bring together bison supporters, including Native Americans, bison producers, conservationists, sportsmen and educators to celebrate the significance of Bison.

It took 4 years and that finally happened on May 9, 2016, when the Bison—and by general consensus, the Buffalo—became our National Mammal with its own special National Bison Day.

The American bison is not only the country’s official mammal; It is also the state mammal of Wyoming, Oklahoma and Kansas. Many towns, creeks and rivers throughout North America bear the name Buffalo or Bison.

Remember that in North America, we regard the terms Buffalo and Bison as interchangeable—no apologies. So use whichever you prefer!

For reference see National Geographic guidelines, and US-based dictionaries, including Websters Collegiate Dictionary, which declare the terms interchangeable. Buffalo has a long history in North America, dating from 1625 when first recorded—even before Bison was first documented, in 1774.

Professor Dale F. Lott, University of California scientist and author of American Bison: A Natural History puts it well, I think.

“I decided to use both names. . . ” he writes, “My Science side is drawn to Bison. Yet the side of me that grew up American is drawn to Buffalo—the name by which most Americans have long known it.

“Buffalo honors its long, intense and dramatic relationship with the peoples of North America.”

Here are 3 of my all-time favorite buffalo stories. Two are gleaned from that master of Buffalo Lore and knowledge—William Hornaday of the original Smithsonian Museum. His book The Extermination of the American Bison, was published by the US Government Printing Office in 1889.

The other story came from Mike Faith, buffalo manager for Standing Rock herds for some 20 years, now Standing Rock tribal chairman.

How will you celebrate the occasion of National Bison Day, Nov 6? I’m starting early by offering you my 3 favorite buffalo stories.

Will you share some of your favorites too? If we start collecting right now maybe we can have them ready by November 6.

First: Here’s my Number 1 Favorite Buffalo Story:

Noble Fathers We Saw in Action

by Francie M. Berg | Jul 14, 2020

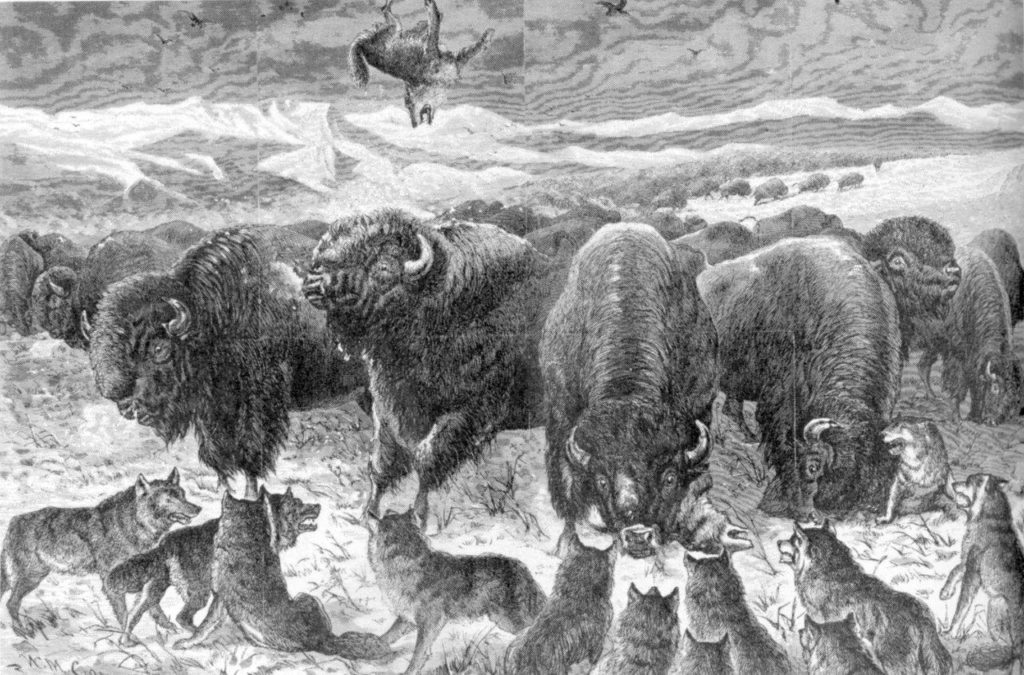

Large gray wolves danced around the circle of bulls in impatient expectancy, licking their chops, while the bulls faced them, snorting and pawing dirt. Painting by CM Russell, The Buffalo Book, David A. Dary.

Buffalo bulls are born with a strong sense of responsibility. The Noble Fathers, they were called in earlier times, for protecting mothers and calves from the ravages of wolves or weather.

When attacked by packs of wolves—and in blizzards and fierce storms, it was said—they form a circle or triangle facing into the wind and shield cows and calves from risks of wintery blasts and vicious wolves.

This remarkable buffalo story—one of my favorites—was told by a medical soldier on the western Plains, back in buffalo hunting days.

One day this army surgeon was out buffalo hunting. As he headed back to camp he saw what he described as “the curious action of a little knot of 6 or 8 buffalo.”

Riding closer, unseen behind the crest of a rocky butte, he noted they were all bulls, standing in a tight circle with their massive heads facing out, snorting and pawing dirt.

A dozen large gray wolves danced around them in impatient expectancy, licking their chops. Now and then a wolf dived in, nipping at buffalo heels.

After a few moments the knot broke up, still keeping its compact mass, and started off for the main herd, a half mile away.

Then to his very great astonishment, the surgeon saw what the bulls were protecting in their midst—a newborn calf trying to stand on wobbly legs.

It stumbled a few paces, then fell back down.

The bulls formed their protective circle again, shaking big heads and stout horns fiercely. The hungry wolves sat back down and licked their chops, awaiting a better chance to attack.

Again, the calf struggled to his feet, stumbled farther ahead, then fell. Each time he fell, he showed a bit more strength The bulls faced out again, fiercely tightening their circle, pawing dust and bellowing.

From his hiding place the surgeon watched this drama play out a few times. The calf struggled ahead, a bit stronger each time before it collapsed. Wolves dove in, snapping at the bulls, got tossed in the air, Furious bulls plunged, pawed dust and slashed with savage horns.

After some time—satisfied that the little calf was safe, the surgeon rode on.

Telling the story later, he said, “I have no doubt the Noble Fathers did their whole duty by their offspring and carried it safely to the herd.”

While the Army surgeon watched, the buffalo bulls protected one small newborn calf until he was strong though to catch up with the herd. Courtesy of National Park Service.

I saw those “noble fathers” in action once myself—and they did protect the buffalo calves.

We were riding horseback in the North Unit of Teddy Roosevelt Park with some friends.

Our kids were teenagers then and we were about 15 riders. As we rode over a hill, we saw—spread out and grazing below us—the North Unit herd of about 60 buffalo.

They looked up, startled by the sudden appearance of so many riders, and began to run. We reined in our horses and paused to watch.

They didn’t run far. The big bulls stopped in an open area and formed a tight circle facing us, shaking their massive heads, while cows and calves took the inside, milling around

It was clearly a defensive position they all understood—and we did too—the calves well-hidden and nosed around by nervous moms in the center, while the bulls came forward—ready and eager to take us on.

Describing a similar defensive move during the 19th century, Colonel R.I. Dodge, wrote in his Plains of the Great West:

“The bulls with heads erect, tails cocked in air, nostrils expanded and eyes that seem to flash fire, walk uneasily to and fro, menacing the intruders by pawing the earth and tossing their huge heads.”

We paused and watched the amazing bulls for awhile, charmed to think that for over 100 years and several generations this herd and their ancestors had lived safely inside the Teddy Roosevelt National Park—with no large enemies to fear.

Yet this generation of noble fathers stood just as ready to fight us off and protect with their lives the young calves and their mothers, just as dozens of observers had described their responses to real dangers long ago.

No hungry wolves would have broken through their defenses that day! No wolves or grizzly bears or hunters.

Of course, we skirted far around the herd and let the buffalo bulls think they had stood off our attack.

(Copyright 2020 by Francie M. Berg. on July 14, 2020, in the blog <BuffaloTalesandTrails.com>, from William Hornaday’s 1889 book “The Extermination of the American Bison,” and a personal family experience.)

Mother Buffalo help each other

My 2nd most favorite story

Francie M. Berg,

Told by Mike Faith, Standing Rock’s Buffalo Manager for some 20 years, now Standing Rock Tribal Chairman.

Mike Faith told me buffalo watch out for each other for warning signs of danger or stress.

When it comes time for a cow to give birth she finds a secluded place such as a ravine with trees. She has time for herself, to be alone there when the calf is born.

There she is able to bond with her newborn, nourish and defend it, until it is strong enough to join the herd.

But she’s not quite alone. The mother has several female friends who hang around—not so close as to interfere, says Faith—but near enough to watch for predators and guard against possible interruptions.

Buffalo cows often watch out for each other, and give help when needed. National Park Service.

“If a new mother is too nervous, gets up and moves away before she’s ready, she might not bond with her calf,” he says.

“If she gets spooked, she might abandon her newborn and not come back. The calf can die of starvation.”

Faith told me that one morning he saw three cows acting in a peculiar way.

They were grazing together on the plateau above a cutbank.

One at a time, each buffalo cow walked over to the edge of the cutbank, looked down on the flat below for awhile and then returned to her grazing.

They stayed nearby and occasionally each one went back and looked over the bank again.

As he sat in his pickup and watched, Faith couldn’t see what the cows were concerned about, but didn’t want to disturb them.

So he drove around where he could see the grassy area below the bank.

There he saw two coyotes circling a young, sleeping calf at some distance.

As he drove closer, the coyotes saw him and started to run.

They disappeared over the hill, but Faith said he had no doubt if the coyotes had come too close to the sleeping calf, the cows would have charged down the steep trail and chased them away.

The buffalo mother’s two friends were helping her keep watch and protect the sleeping calf.

(Copyright 2020, as told to Francie M. Berg by Mike Faith, Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Chairman, Ft. Yates, ND.)

Great Indian Buffalo Horses

My 3rd most Favorite Buffalo Story

by Francie M. Berg, Jun 30, 2020

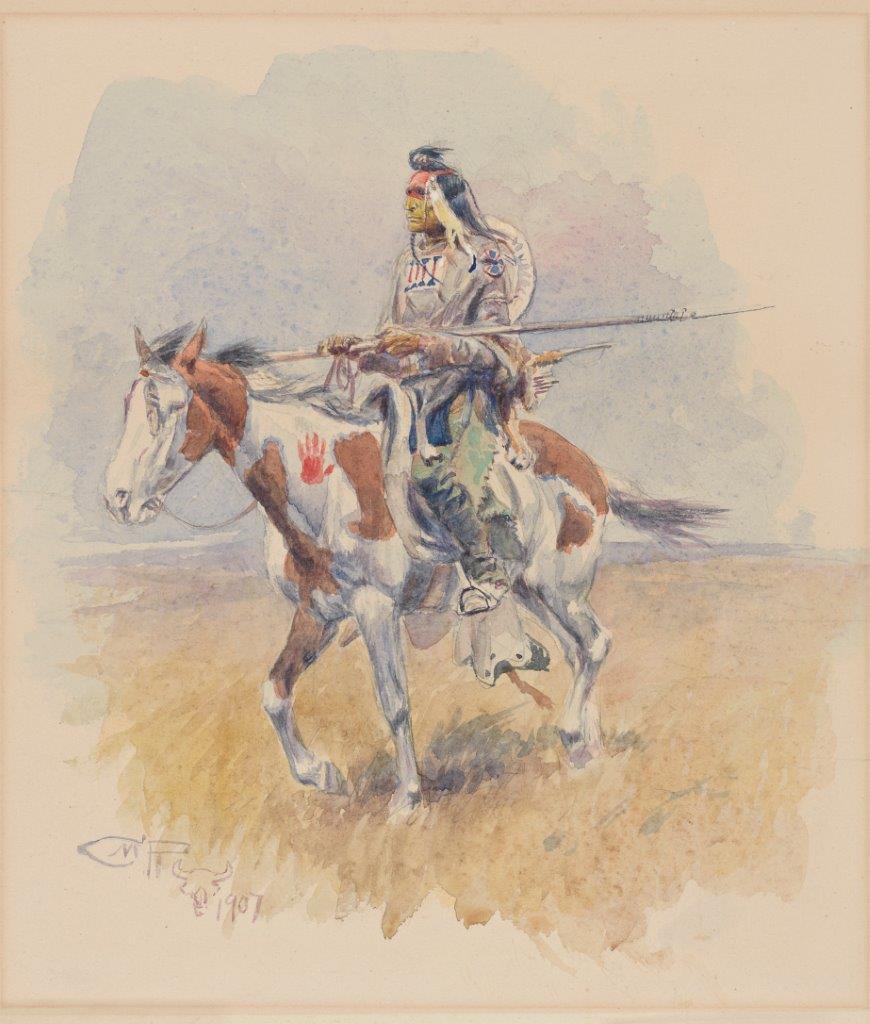

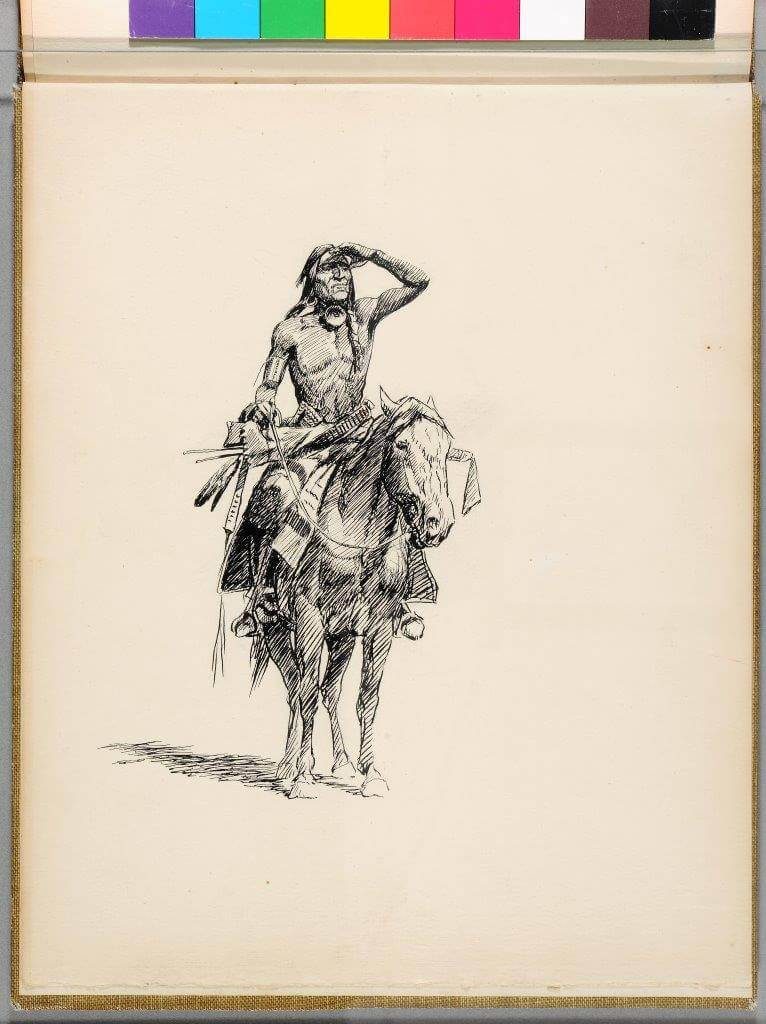

According to all accounts Indian buffalo hunting horses were better trained for the job than those of white hunters, reported William Hornaday. Painting by CM Russell.

Painting by CM Russell, Amon Carter museum.

According to all accounts, the Indian buffalo hunting horses were better trained for the job than those of white hunters, reported William Hornaday. He credited this to the fact that Indian hunters shooting with bow and arrows required free use of both their hands.

This was only possible when the horse took the right course of its own free will and held close to the buffalo during a charge—as guided by knee pressure alone.

“Indeed,” he wrote. “In running buffalo with only the bow and arrow, nothing but the willing cooperation of the horse could have possibly made this mode of hunting successful.

“But for the willingness and even genuine eagerness with which the buffalo horses entered into the chase, hunting on horseback would have been attended with almost insurmountable difficulties.”

Indian horses seemed to take special pleasure in running buffalo.

William Hornaday noted that the explorers, Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark were impressed with the passion for buffalo hunting of the Indian horses they purchased from the Shoshones in trade for their journey across the Rocky Mountains.

After they had traveled to the Pacific Ocean and back, they re-crossed the Continental Divide, and then divided their party.

Clark took the horses on the southern route through rich buffalo country along the Yellowstone River.

He delegated their 49 Indian horses to Sergeant Pryor with a couple of riders to bring downriver, while to save time he and the others went on boats that they built, mostly of cottonwood trees.

But he got a complaint from Sgt. Pryor, who sent word that he needed at least one more rider.

It was almost impossible, Pryor reported, to drive their horses along the shore with the help of only two men.

There were so many herds of buffalo grazing on the rich grasses of the Yellowstone Valley, and the Indian horses were so eager to hunt them, that they tried to roundup every herd they saw.

“In passing every gangue of buffalow, the loos horses immediately set off in pursuit of them, and surrounded the buffalo herd with almost as much skill as their riders could have done,” Clark wrote in his journal.

“All those that speed sufficient would head the buffalow and those of less speed would pursue on as fast as they could.”

Sgt. Pryor found the only practical method was to have the extra man ride ahead—and whenever he saw a herd of buffalo to chase them off before the main horse herd came close enough to pursue them.

As reported by Hornaday, the Hon. H.H. Sibley also told of the dedication of one horse that had lost its rider on a Red River Metis hunt.

An experienced buffalo horse “continued the chase as if he of himself could accomplish great things, so much do these animals become imbued with a passion of this sport!” CM Russell painting.

“One of the hunters fell from his saddle and was unable to overtake his horse, which continued the chase as if he of himself could accomplish great things, so much do these animals become imbued with a passion of this sport!”

Another hunter who left his favorite buffalo horse in camp for a day’s rest, asked his wife to tie the horse. But the horse pulled loose and galloped off to join the hunt.

“The chase ended. He came neighing to his master—who he soon singled out.”

“He continued to keep pace with the hunters in their pursuit of the buffalo, seeming to await with impatience the fall of some of them to earth.

“The chase ended. He came neighing to his master, who he soon singled out, although the men were dispersed here and there for a distance of miles,” wrote Sibley.

(Copyright Jun 30, 2020, by Francie M. Berg from the blog <BuffaloTalesandTrails.com> quoting from William Hornaday’s 1889 book “The Extermination of the American Bison,” and the “Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 1804-1806.”)

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog