Below are 3 bright slices of the rich heritage of Wind Cave National Park in South Dakota.

First: In the video below the fine storyteller Sina Bear Eagle tells the beautiful Lakota tradition of Wind Cave as the place from which humans and bison emerged in ancient times.

Second: Briefly, what’s the history of Wind Cave National Park from the time President Theodore Roosevelt established it Jan 3, 1903, with its own genetically pure herd of bison from the New York Zoo? At 154 miles of explored passageways (so far) the 7th longest cave in the world . . .

Third: A bright new segment captivates a female student from the Latino Heritage Intern program. New generations, new enthusiasm for conservation and wildlife.

So let’s relax and enjoy these segments of the wonderful heritage of Wind Cave National Park.

The Lakota Emergence Story

Sina Bear Eagle tells her Cheyenne Creek community version of the Lakota Emergence Story that comes from the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation.

In Lakota culture, history is passed down to new generations through the spoken word. There are many different versions of the Emergence Story, varying from band to band and family to family.

This version comes from the Cheyenne Creek community on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation of the Oglala Lakota tribe. The story was told by Wilmer Mesteth—a tribal historian and spiritual leader—to Sina Bear Eagle, who retells it in the following passage.

This story begins at a time when the plants and the animals were still being brought into existence, but there were no people or bison living on the earth. People at that time lived underground in the Tunkan Tipi—the spirit lodge—and were waiting as the earth was prepared for them to live upon it.

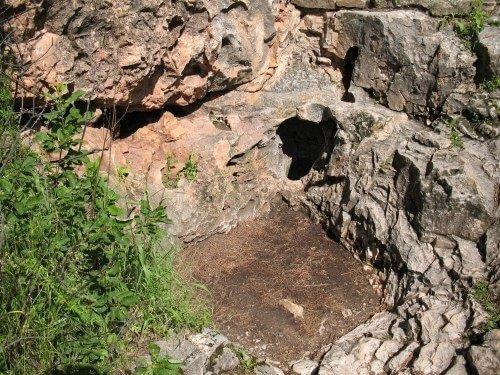

The Natural Opening of Wind Cave. Can you hear the “breathing earth” through the hole?

To get to the spirit lodge, one must take a passageway through what the ancestors referred to as Oniya Oshoka, where the earth “breathes inside.”

This place is known today as Wind Cave, referred to in modern Lakota as Maka Oniye or “breathing earth.” Somewhere, hidden deep inside this passageway, is a portal to the spirit lodge and the spirit world.

There were two spirits who lived on the surface of the earth: Iktomi and Anog-Ite.

Iktomi, the spider, was the trickster spirit. Before he was Iktomi, his name was Woksape—“Wisdom”—but lost his name and position when he helped the evil spirit Gnaskinyan play a trick on all the other spirits.

Anog-Ite, the double face woman, had two faces on her head. On one side, she had a lovely face, rivaling the beauty of any other woman who existed. On the other, she had a horrible face, which was twisted and gnarled. To see this face would put chills down any person’s spine.

Anog-Ite was once Ite, the human wife of the wind spirit Tate. She longed to be a spirit herself, so when the evil Gnaskinyan told her dressing up as the moon spirit, Hanwi, would grant her wish, she followed without question.

Gnaskinyan used both Ite and Woksape as pawns in his trick on the other spirits.

The Creator, Takuskanskan, decided not to punish Gnaskinyan for this trick, because evil does what’s in its nature.

Woksape and Ite were both punished because they let their pride determine their actions and allowed themselves to be guided by evil, when both should have known better.

Takuskanskan transformed the two into Iktomi and Anog-Ite, allowing Iktomi to play tricks forever and Anog Ite to be the spirit she desired to be. Both were banished to the surface of the earth.

Iktomi and Anog-Ite had only each other for company. Iktomi spent his time playing tricks on Anog-Ite, torturing her and never allowing her to live in peace, but this pastime soon bored him.

He wanted new people to play tricks on, so he set his sights on the humans. He knew he needed help for this trick; he asked Anog-Ite, promising he’d never torment her again. She agreed to these terms and began loading a leather pack.

Anog-Ite filled this pack with buckskin clothing intricately decorated with porcupine quills, different types of berries, and dried meat. She then loaded the pack onto the back of her wolf companion, Sungmanitu Tanka.

When the wolf was ready, Iktomi led him to a hole in the ground and sent the wolf inside Oniya Oshoka to find the humans. The wolf followed the passageways until it met the humans.

A lone wolf. Anog-Ite’s wolf was named Sungmanitu Tanka. Credit NPS Photo by Jacob W. Frank.

Once there, he told the people about the wonders of the Earth’s surface, and showed them the pack on his back. One man took out the buckskin clothing and felt the soft leather. His wife tried on a dress and when he looked at her he thought the dress accentuated her beauty.

Next they took out the meat, tasted it, and passed it around amongst some of the people. The meat intrigued them. They’d never hunted before, and had never tasted anything like meat. They wanted more.

The wolf told them if they followed him to the surface of the Earth, he’d show them where to find meat and all the other gifts he brought.

The leader of the humans was a man named Tokahe—“The First One”—and he refused to go with the wolf. He objected, saying the Creator had instructed them to stay underground, and that’s what he’d do.

Most of the people stayed with Tokahe, but all those who tried the meat followed the wolf to the surface.

The journey to the surface was long and perilous. When they reached the hole, the first thing the people saw was a giant blue sky above them. The surface of the earth was bright, and it was summertime, so all the plants were in bloom.

The people looked around and thought the earth’s surface was the most gorgeous place they’d ever been before.

The wolf led the people to the lodge of Anog-Ite, who was in disguise; she had her sina—“shawl”—wrapped over her head, hiding her horrible face and revealing only her beautiful face.

Anog-Ite invited the people inside, and they asked her about the clothes and the food. She promised to teach the people how to obtain those things, and soon she taught the people how to hunt and how to work and tan an animal hide.

This work was difficult, however. The people had never struggled like this in the spirit lodge. They grew tired easily and worked slowly.

Time passed, and summer turned to fall, then to winter. The people knew nothing about the Earth’s seasons and had worked so slowly that, by the time the first snow came, they didn’t have enough clothes or food for everyone.

They began to freeze and starve. They returned to the lodge of Anog-Ite to beg for help, but it was then that she revealed her true intentions.

She ripped the shawl from her head, revealing her horrible face, and with both faces—beautiful and horrible—laughed at the people.

The people recoiled in terror and ran away, so she sent her wolf after them to chase and snap at their heels. They ran back to the site of the hole from which they’d emerged, only to find that it had been covered, leaving them trapped on the surface.

Two buffalo at Wind Cave. NPS.

The people didn’t know what to do nor where to go, so they simply sat down on the ground and cried.

At this time the Creator heard them, and asked why they were there. They explained the story of the wolf and Anog-Ite, but the Creator was upset.

The Creator said, “You should not have disobeyed me; now I have to punish you.” The way the Creator did that was by transforming them—turning them from people into these great, wild beasts. This was the first bison herd.

Time passed, and the earth was finally ready for people to live upon it.

The Creator instructed Tokahe to lead the people through the passageway in the cave and onto the surface. On the way, they stopped to pray four times, stopping last at the entrance.

On the surface, the people saw the hoof prints of a bison.

The Creator instructed them to follow that bison. From the bison, they could get food, tools, clothes and shelter. The bison would lead them to water. Everything they needed to survive on the earth would come from the bison.

Buffalo along the road in Wind Cave National Park.

When they left the cave, the Creator shrunk the hole from the size of a man to the size it is now, too small for most people to enter, to serve as a reminder so the people would never forget from where they’d come.

Bison Bellows: Wind Cave National Park—Riding the Rails Back Home

Buffalo at the entrance to Wind Cave National Park, Visitor center. Photo courtesy of Greg Schroeder.

Before the mid-1800s, bison dotted the South Dakota plains.

But by the 1890s, South Dakota resembled a bleak wildlife landscape. The wild free roaming bison were gone and so were the elk, the pronghorn, other wildlife and the people that once roamed freely across the plains.

By the 1900s some efforts were underway locally to restore prairie wildlife; yet, it wasn’t until people on the east coast gathered together to create the New York Zoological Society in 1905 and its subdivision of the American Bison Society, led by William Hornaday and President Theodore Roosevelt that bison conservation actually began to have a home.

In 1913, the New York Zoological Society raised sufficient numbers of bison that they could imagine doing something that had never been done before. They proposed a new vision of conservation partnership between private and public entities, in order to donate and restore bison to Wind Cave National Park nestled in the South Dakota Black Hills landscape.

In November, 1913, 14 bison departed New York City by train for the long trip westward back home to Hot Springs, South Dakota and then by wagon to Wind Cave National Park.

This cross-country movement of bison, from private possession to public lands, represented a major milestone in wildlife conservation.

The 14 bison multiplied rapidly among the pines in the Black Hills of South Dakota in Wind Cave National Park. Photo courtesy of Greg Schroeder.

It is interesting to visualize enthusiastic crowds gathering at train stations to see the 14 bison from New York City heading home westward.

It may be that some of those communities included people who earlier rode the same rails westward in order to decimate wild bison.

The story of bison restoration at Wind Cave National Park is one of remarkable change in societal intent and perception, and one of how a small yet determined society can transform the attitude of a nation.

Although bison suffered an unnatural and traumatic population decline, the Wind Cave bison herd now serves as a foundation for future conservation.

Those 14 bison in 1913 were the beginning of over a century of bison conservation at Wind Cave National Park. They have served as a source of bison to reestablish other herds across the United States and most recently in Mexico and have brought delight and inspiration of millions of park visitors and supporters of the National Park Service.

According to the Lakota people, Wind Cave is the place from which Wakan Tanka, or the Great Mystery, sent bison to the Sioux hunting grounds through a person, known as the buffalo woman, who ascended from Wind Cave to give the Lakota people bison.

Surveying Buffalo at Wind Cave National Park

in the Latino Heritage Internship Program

by Nicole Segnini , Intern, Office of Communications

”I never thought I would learn so much about wildlife in such a short time and be interested in learning more.”

S’mores, late-night card games, embarrassing stories, trying to light up a fire, seeing bison for the first time, learning about Lakota culture, and seeing Cave Boxwork for the first time.

That’s a summary of what I did with a team of interns from the Mosaics In Science and Latino Heritage Internship Program, with some of the Environment for the Americas (EFTA) staff.

Our team: Yuyavan, Paola, Brooke, Will, Shanelle, Griselda, Sheylda and Jedi. The team was full of incredibly smart people whom I learned so much from. I never thought I would learn so much about wildlife in such a short time, and be interested in learning more.

“Our team—we learned about the park’s extensive prairie landscape and its wildlife and helped the park’s wildlife biologist count their bison.”

We went to South Dakota, land of lots of cows, and Wind Cave National Park. During the trip, we learned about the park’s extensive prairie landscape and its wildlife (especially bison and prairie dogs) and helped the park’s wildlife biologist do a count of bison.

I have always cared about animals and wildlife and their conservation. But hearing all of them talk about specific issues, encouraged me to learn more and be more proactive in learning about important wildlife conservation efforts.

At Wind Cave, we did a Natural Entrance Cave Tour and learned about its discovery, where it got its name, and its significance in Lakota culture.

We saw its incredible and unique boxwork throughout the tour. Boxwork is made of thin blades of calcite that project from cave walls and ceilings, forming a honeycomb pattern.

At one point the lights were turned off, so we could see how it really looks inside the cave. I may have (or may have not) been a tiny bit scared… it was pitch black. It is crazy to think that back in the day people would explore the cave with just a candle…

Our guide, Angela, who is the park’s wildlife biologist, was amazing. She talked about the park’s bison herd and conservation efforts, but she also taught us about other wildlife in the park, like pronghorns and prairie dogs!

After some sandwiches, we headed out to “hunt” bison. We did a bison count or bison survey. This means: we found the park’s herd and counted how many bison and calves were in it.

Discovering bison for the first time. “I counted about 114—from a safe distance.”

A regular count helps Wind Cave keep track of how fast the bison population is growing and can monitor the herd to make sure the animals, and their habitat, are protected and conserved for future generations.

By the end of the count, between 110 to 130 bison, including 12 calves, were observed. I counted about 114. Of course, our count was done from a safe distance. (We did NOT pet the fluffy cows!!).

This was not only a great educational opportunity for us, but it was also a great way to connect with people who share the same love for nature and conservation and to experience the outdoors as some of us had never done before.

Some of us had never even seen a bison (now I have seen quite a few!), others had never gone camping! This trip also encouraged me to learn more about conservation efforts and wildlife at our parks and to head outside to discover.

I am very thankful to Environment for the Americas for allowing me to be part of this amazing adventure!

I am so happy I met Brooke, Yuya, Will, Paola, Shanelle, Griselda and Sheylda. I think we were a great team and worked well with each other. I loved hearing from them about their work, projects, passions, backgrounds and families and sharing things in common with one another.

BONUS! Bison from Custer State Park came to visit us at our camping site!

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog

Thank you Francie for collecting stories to help celebrate National Bison Day. I certainly enjoy your blogs and have learned SO MUCH from them over the years!! I hope my hunting story might be appropriate. Many thanks! Russell

Thanks Russell.

I love your story—and also the quotes. Especially the John Mason one, “I do not hunt for the joy of killing but for the joy of living, and for the inexpressible pleasure of mingling my life, however briefly, with that of a wild creature that I respect, admire and value.”

That certainly expresses my hunting experiences growing up. And thanks for volunteering for a Guest Blog! Your timing was perfect!

Best wishes, Francie