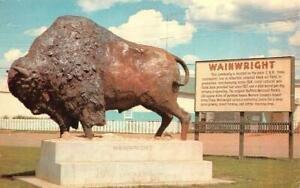

Today a magnificent, lunging buffalo bull statue greets visitors in Wainwright with a silent bellow. It was erected just off the highway on Main Street in July 1965 in memory of the great buffalo herds that once roamed Buffalo National Park. The unveiling attended by many townspeople—including a group of Buffalo Riders who rode the range in the buffalo park. Sculptor, Heiko Hespe.

Wainwright, Alberta, is a midsized town in the Canadian Great Plains with a tumultuous buffalo legacy. It lies east of the Rocky Mountains just west a few miles from the Saskatchewan border and to the northeast of Calgary.

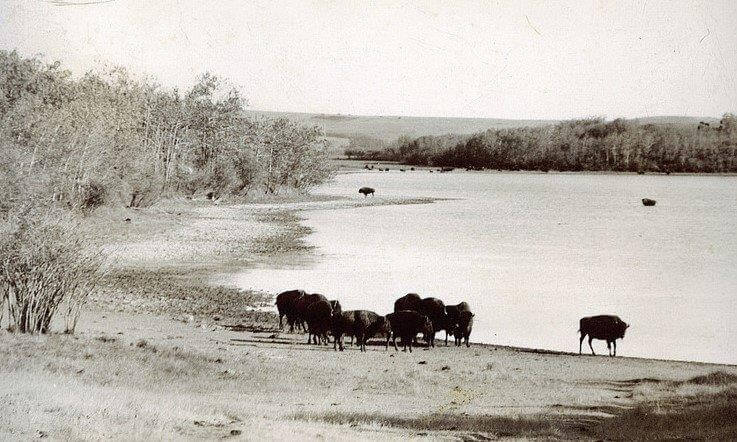

From ancient times buffalo grazed those northern grasslands by the millions. Then they were gone—every single one—seemingly for good. Suddenly they returned and multiplied again to many thousands—for 30 years—then totally vanished again.

Today a peaceful “Bud Cotton Buffalo Paddock” stands at the entrance to Camp Wainwright in celebration of that rich buffalo heritage.

Four yearling bison, donated by the Superintendent of Elk Island National Park to commemorate that plains-bison-saving-effort at Buffalo National Park from 1909 to 1939, have grown to a stable 35 head. Also today a magnificent, lunging buffalo bull statue greets visitors with a silent bellow.

What happened during those 30 chaotic years? And who was the legendary Bud Cotton?

This is the story of those 30 years and Bud Cotton’s tribute to his Buffalo Roundup Gang and their stories.

Every school child in Wainwright knows what happened. Their fathers, grandfathers or uncles maybe rode with Bud Cotton in the great buffalo round-ups between 1909 and 1939.

Bud Cotton is a legend. He didn’t forget. In fact, he wrote down the stories. They’re well known in Wainwright.

Bud Cotton’s stories are today family tales told around campfires and in lecture halls.

Great Days—Never to be Forgotten!

“Great days!” Bud Cotton recalls. ”The Buffalo Riders will never forget!”

“Frost bites and bruised bones healed and were forgotten. But memories of hard rides and frozen sandwich lunches, out in the Park hills, a blazing fire to help drive away the frost from tingling toes and cold-seared faces. You would be roasted on one side and froze on the other.

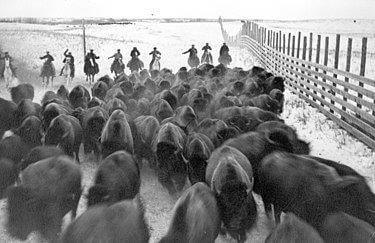

Bringing them in to the corrals against the drift fence at Wainwright on a dead run! The buffalo bore some scars—and so did the Buffalo Roundup Riders.

“Buffalo we had corralled, branded and manhandled by the thousand bore some scars and brands. But then the riders still bear scars and sore bones as mementoes of those same good old days!”

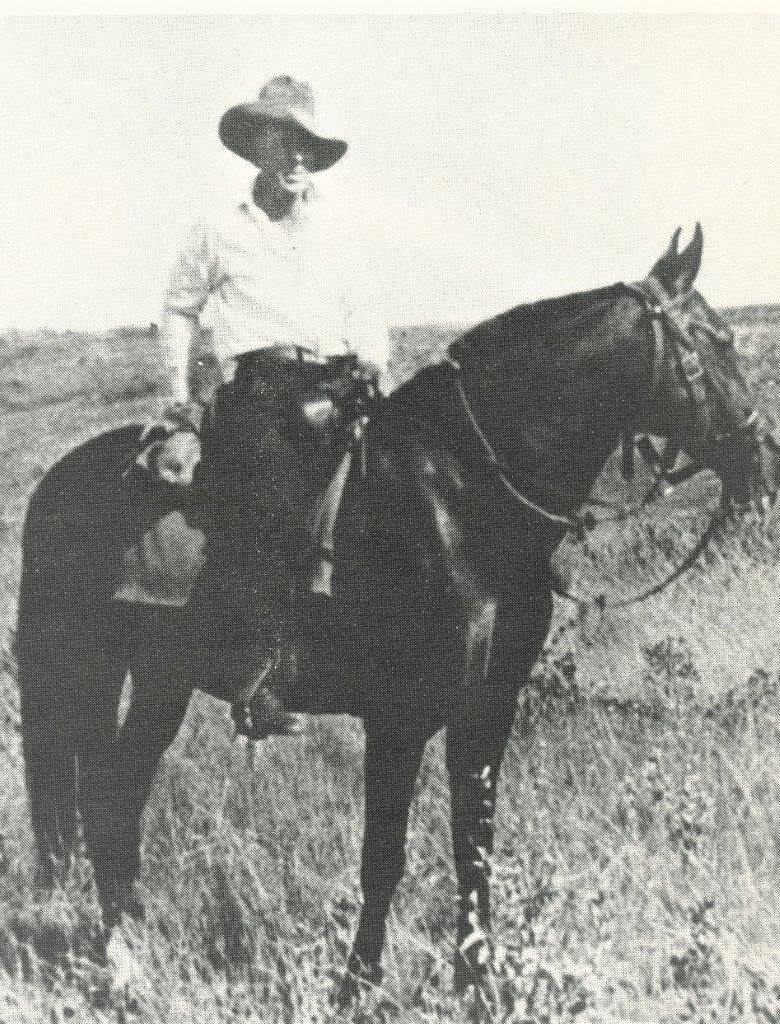

From 1912 through 1940, E.J. (‘Bud’) Cotton was the Buffalo Park Warden at Wainwright, Alberta.

An old-fashioned buffalo handler who rode hard and worked his crew hard in the worst possible winter weather, he arranged for his men to change their lathered-up horses each noon–with fresh horses for the always-challenging afternoon ride.

Cotton hired a hard-riding Buffalo Roundup Gang—as he called them—for ‘fall’ roundup, which they tackled in stride during the coldest days of winter when buffalo hides were prime.

Long before the advent of low-stress handling practices were being advocated for buffalo, the buffalo herds were literally wild animals, and they came stampeding between the drift fences toward the open gate at a dead run.

Cotton said his corral fences looked strong enough to hold an elephant “but just stick around until we run a bunch of buffalo into them, then watch the splinters fly!”

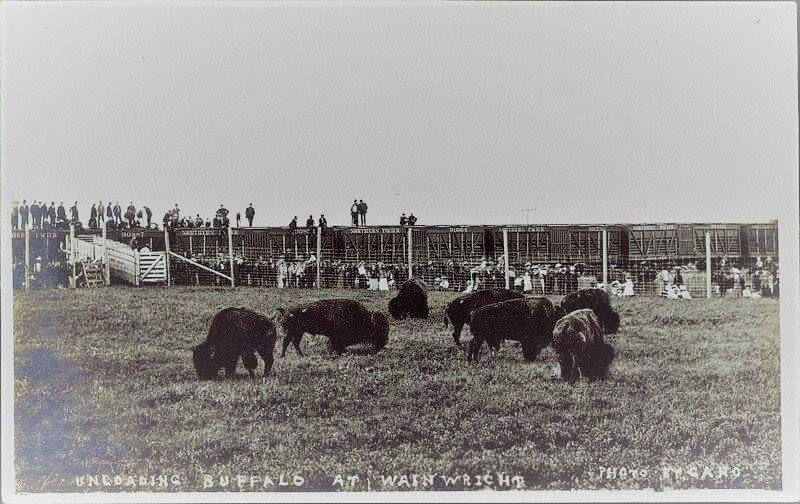

When the second wave of buffalo arrived at Wainwright in 1909 they were welcomed with joy. The town was waiting.

Canadian officials realized their plains buffalo were fast disappearing and began their search for ways to repopulate their grasslands with buffalo before they went extinct.

They found it south of the border in Montana in the healthy, growing buffalo herd owned by Michel Pablo and Charles Allard on the Flathead Indian Reservation.

With settlers closing in on them, the Montanans were losing their free range on Indian land by the turn of the century. Pablo, the surviving owner, decided to sell. He hoped to sell them to the US government, but his offer was scorned in Washington.

Canada offered to pay Pablo’s price for the whole herd of some 300 head at $200 each plus $45 for shipping by rail. Rounding up the buffalo and getting them to the shipping point in Ravali MT was not easy—it took Pablo and his round-up crew 6 years. By then he had twice that many to sell.

Meanwhile, 9 miles south of Wainwritght the handlers were hurrying to complete a 9-foot wire fence built around 200 square miles to hold them.

The first year, 1907, 411 buffalo made the 1,200 mile journey switching over onto five railway systems in all. The destination was to have been Wainwright, but because the fences were not finished there, they lived at Elk Island Park for a time.

Two years later the herd was moved to Wainwright except for 49 strays which could not be captured—they formed the first herd in Elk Island Park.

Unloading buffalo from the freight train at Wainwright.

In July the Wainwright Star reported that 190 additional buffalo had arrived and approximately 150 head would be shipped later . . .

In total, Michael Pablo shipped 716, according to Canadian buffalo historian Valerius Geist. Canada paid $245 each, including the same for each newborn calf.

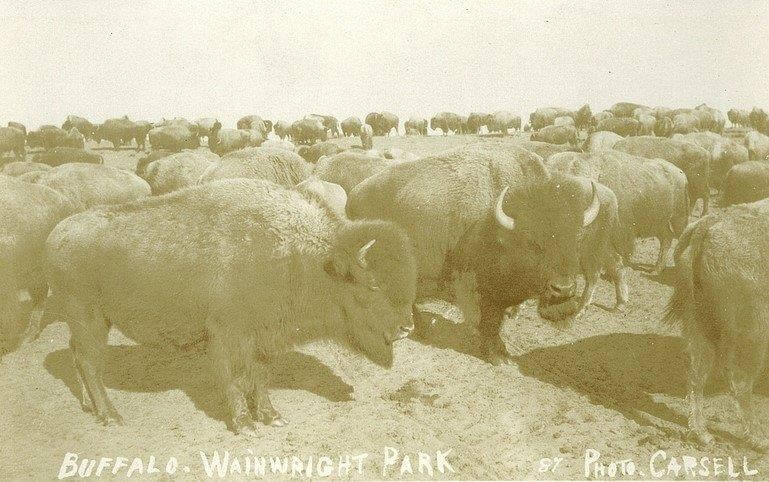

By 1910 the count was 800 buffalo, 2 moose, 4 elk and 36 deer which got fenced in too. Later 13 antelope, 11 moose and 2 more elk were added.

In 1923 the Hollywood movie “The Last Frontier” was filmed at Wainwright. The Park Riders were signed up as stunt men and extras.

Buffalo were also shipped to zoos and parks all over the world.

Bud Cotton’s Buffalo Roundup Gang

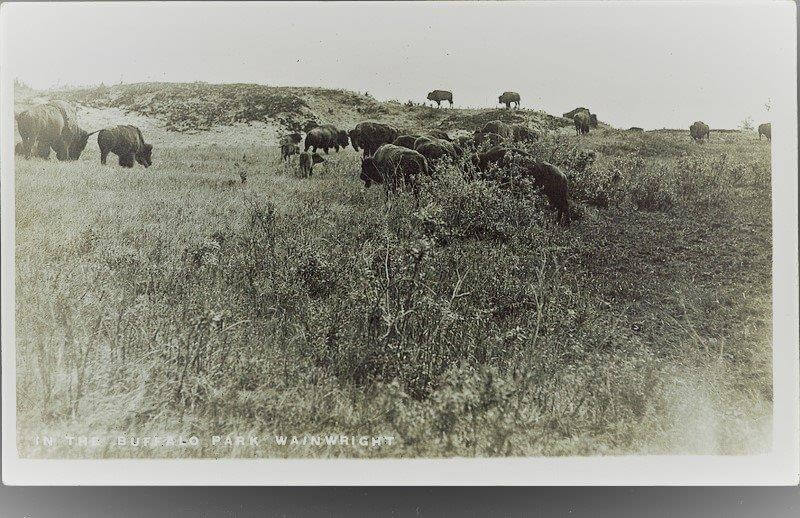

For the first 10 years the buffalo herd at Wainwright was allowed to multiply naturally. But soon it was growing too fast even for its 200-square mile range. Every few years the whole herd doubled in size—and then doubled again!

For the first 10 years the buffalo herd at Wainwright was allowed to multiply naturally. It doubled—and then doubled again.

Only a few head were corralled now and again and shipped to England, Ireland, Germany and Italy and to various parks in the US and Canada. Still the healthy herd multiplied.

Something had to be done to curb the growth. The decision was to build a slaughter house and sell prime buffalo hides and meat.

Bud Cotton hired a hard-riding Buffalo Roundup Gang—as he called them—for ‘fall’ roundup, which they tackled in stride for 19 years during the coldest days of winter when the hides were prime.

Long before the advent of low-stress practices were advocated for handling buffalo, they were generally treated like cattle—expected to respond like cattle.

Instead buffalo responded like deer, elk and other wild animals, and they stampeded between the drift fences at the Wainwright pasture toward the gate at a dead run.

But buffalo are not cattle—they were literally wild animals.

Cotton said their corral fences looked strong enough to hold an elephant “but just stick around until we run a bunch of buffalo into them, then watch the splinters fly!”

He praised his Buffalo Riders for their toughness and endurance.

“Bert Kitchen should still show some scars,” he wrote.

“We happened to be heading fast through a narrow draw on the high lope, eight riders strung out head to tail, trying to head off a bunch of break-away buffalo.

“Bert was in the lead when his horse went down, some of our horses jumped over him and some just walked down his lanky frame. Our horses were all shod with ‘never-slip’ or Spade Caulks.

“We all sighed ‘Poor Bert,’ but by the time we had circled back to the rescue, Bert had picked himself out of the snow and was mounted again, and mumbled something about how he had busted his cigarette lighter.

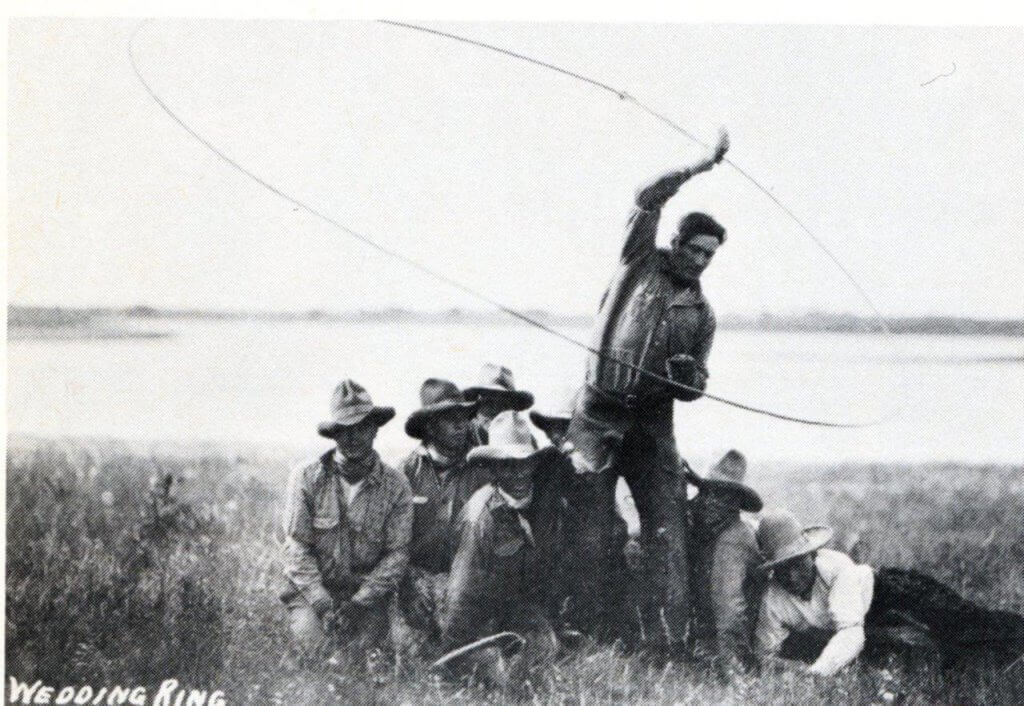

Vern Treffry holding a buffalo calf.

“Vern Treffry will always remember his grand slide down Jameson Lake hill. It was sure hard on his vest buttons, but he made it down to the bottom and headed the buffalo while his saddle horse looked on from the top of the hill, one leg still jammed deep in a badger hole.”

“Hi Dunning tied onto a balky buffalo cow and hitched her hard and fast onto his saddle horn. Now a buffalo cow is not bashful. Things started to happen fast!!

“First his saddle cinch loosened and the saddle started to turn. About that time his horse just didn’t like the looks of the buffalo cow so close and hooked one hind leg over the taut rope and started to buck.

“Hi was sure in the middle of trouble with no hope of getting that hard knot from the saddle horn.

“Warren Blinn rides in close and cuts Hi’s new rope, thus leaving Hi and his horse free from the now thoroughly peeved buffalo.

“Still Hi was uncertain whether to bless Warren for saving him from a real dirty mix-up, or to cuss him for cutting his brand new Italian hemp lariat!

“Jack Johnston, he too was on our Riding Crew. He raced his buckskin pony ahead to open a gate for us, but apparently the buffalo were coming just too fast. Guess about 20 head of buffalos ran over him. Lucky though, they were ‘light shippers’ so Jack was able to keep his date down Greenshilds way that night.

“Dick McNairn rode with the roundup crew for many a winter and could tell you tales of fast running buffalo and cold miles of saddle polishing.

“Dick riding hard and close, trying to haze in a big grumpy buffalo bull on one of our roundups. Down goes his horse in a slitherin’ roll, the bull whirls and stands there looking Dick right in the eye.

“Dick was pinned down by one leg as the horse rolled, but he looked that old bull right in the eye. The bull snorted and loped away just as we were riding up to unscramble one lone rider.

“Felix Courier could tell you tales too. On one roundup his horse fell and left him on foot bout ten miles out around Sandhill Corner.

“His saddle horse came in with the bunch, so we sent out the truck to pick up what could be a busted-up rider.

“He was OK, tho a little perturbed about getting cold beans for supper at camp.

“One real bad mix-up Felix got into was when we were running a fast bunch into the corral approaches, racing close in on the drag of a packed herd of a couple hundred buffalo.

“Suddenly the bunch split around a heavy clump of willow. This left him smack in front of the obstacle.

“His horse piled up on the willows and we had to pry Felix loose. He cussed the saddle horse and the buffalos a little and complained of being a little stiff the next day, but was still chasing buffalo on the roundup.”

“We had about 12 regular riders on the roundups.

“We always looked forward to the times that the Gang rode together. Taking hard knocks, broken bones and bitter cold weather as a matter of course, our riders came back year after year, because there was something fascinating and a surging exhilaration that only the Buffalo Riders will ever know.

Bert Kitchen with his trick roping corralling the Gang instead of the Buffalo.

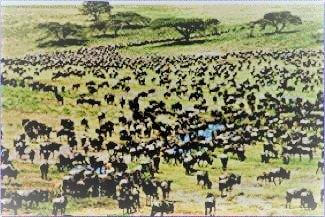

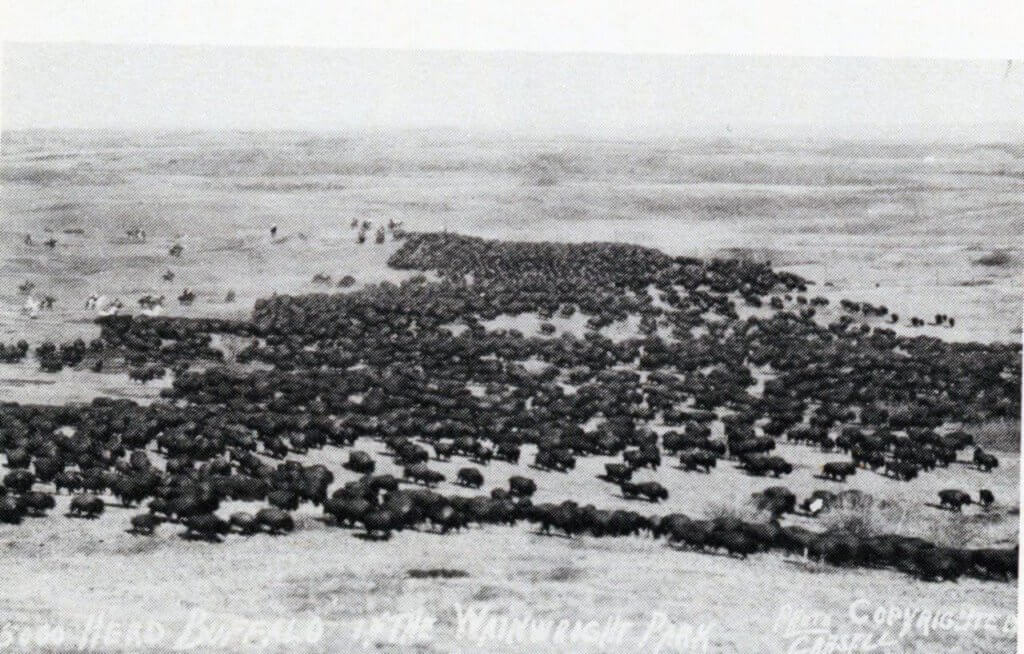

“Only these riders experienced the thrill of careening over an open Range for miles with 5,000 to 8,000 buffalo thundering along in flying dust of snow clouds.

“Park Regulations prohibited any visitors on our roundup drives, so We the Crew rode alone to sights and scenes that we will never forget.”

First roundup

The first roundup was in 1921—it extended into January.

Said one park rider, “Despite below zero weather, icy range conditions and deep snow and roundup—corralling and cutting out of beef from the main herd continued. It was cold, hard riding but we—the riders—always had the buffalo at the slaughterhouse and never held up the butchering crews.

“On the first buffalo roundup, the main herd had never been corralled and did not know what a gate was for. So both the buffalo and the park round-up crew had lots to learn.

“We learned fast that the buffalo could outrun and outwind our horses as we tried to run them over 20 miles, through bush, sand ridges and snow-covered badger holes.

“The herd in 1921 was a little over 4,000 head . . . and wild!

“I have seen us riders pick up around 1,000 head in the Battle River hills and riding our horses to a frazzle towards the corrals on the dead run . . . were lucky if we were successful in getting 200 or 300 in our corrals.

“I might add that on some days we landed at the bunk house with no buffalo to show for the hard day’s ride!”

You might wonder: Why were the Roundup Riders working so hard with buffalo in the coldest part of winter? When, unlike this, cattlemen roundup, sort and sell during the often-delightful golden days of fall.

Cotton explains the difference: “With cattle we don’t worry about how prime the hides are. Down on the big cattle ranches—roundups for beef are pretty well all finished up by the time snow hits.

“With the buffalo it’s different, as both beef and hide count, and the buffalo’s hide is not considered prime until December or later.

“This hide, when prime, makes beautiful robes and coats. That’s why you will hear of riders hitting the roundup trails in 40 below zero weather, right up to their necks in snow banks.”

A typical Buffalo Roundup day with Bud Cotton

At one point in his memoirs Bud Cotton suggests we ride along with him for a typical day on a Buffalo Roundup.

In his own western vernacular, he writes, “Throw a gallon of oats into that lop-eared saddle pony of yours, Stranger. Then we’ll lope along to the ranch for a day or so with the round-up crew.

“Two hundred square miles of range, sandhills, muskeg and brush, 8,000 buffalo to find and run into the corrals. Come along with the gang. We’re headed out for those sand ridges you can see some 12 miles west.

“We’re headed out for those sand ridges you can see some 12 miles west.”

“Just stick close to one of the riders when we start them on the run. If your horse goes into a nose dive and leaves you afoot, just hit for the top of a butte. We’ll come back and pick you up later, for once we start buffalo running we can’t leave them till we hit the corrals.

“Where will your horse be? Why he’ll be running with us.

“There’s the buffalo! About a thousand, spread out and grazing contentedly among the sand dunes. Sure a great sight! To look at them you would never think they could run, would you?” Get ready, they can—40 miles an hour! And they can spin on a dime! Photo Wainwright Park, by Carsell.

“Getting pretty close now. Some of the riders have circled wide and are closing in around the bunch and the buffalo are getting restless at the sight of saddle horses.

“A bull here and there is pawing dirt and snorting. A tail goes up—and the Mammy buffalo start fretting over their calves.

“Then with a thunder of hoofs the whole bunch are off at a pace that makes your horse stretch himself and the wind and dust bring tears to your eyes, as with nerves atingle you try to stay with the racing herd.

“This is no range steer round-up. The pace is too fast. Fast as a wild horse round-up only worse. Buffalo will not bunch when driven, but try to break away in small bunches, every direction.

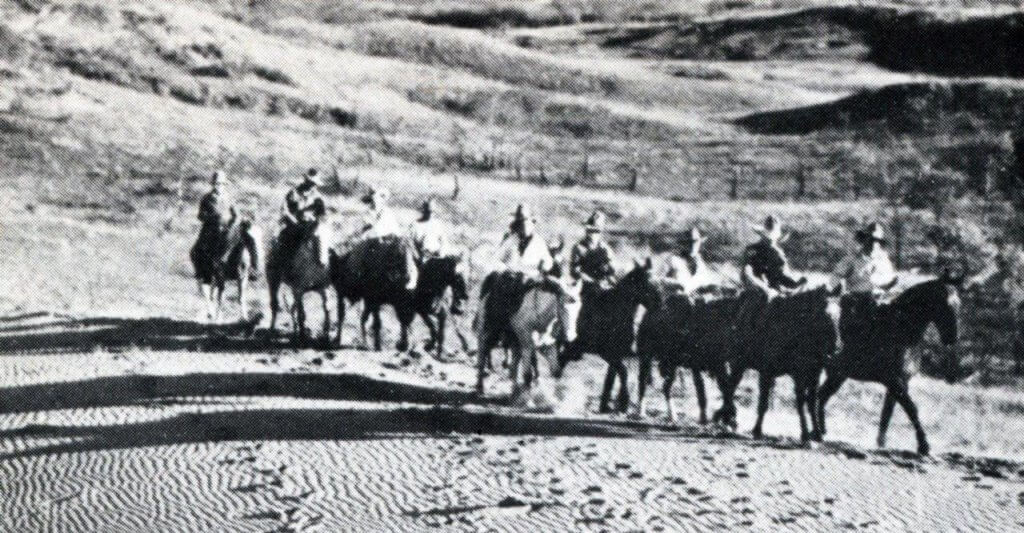

“So you go careening along over the hills in the wake of the herd. The leading buffalo are a full mile ahead, with some of the riders on either flank working like Trojans to keep them heading in the right direction.

“As you see more small bunches break away from the riders and into the sand ridges you think, ’What’s the use of trying to hang on to those crazy brutes? We won’t get them near the corrals, let alone into them.’

“Then you hold your breath and all leather that’s within reach as your horse slides down a sand bank and all but stands on his nose.

“You just get your breath back again when a howl from a racing rider off your left tells you to look out! Here she comes!

“A COMING IS SHE . . . with blood in her eye. You have got between a mammy buffalo and her winded calf.

“Right under your horse’s tail! Giddup! Gee! Bet you wish you could step on the gas. Your horse carries you safely away from the indignant old mother buffalo!

“You heave a sigh and wonder what’s next. ’Don’t get bogged in muskeg,’ howls a rider on your right as you top the sand ridge.

“Cresting the ridge and as your horse slides and leaps down into a heavily timbered valley, you catch a glimpse of drift fences and corral gates two miles away on the other side.

“The only way you know there are any buffalo is by the snorts and crashing of brush as the brutes tear through. Then ‘Ker-splash!’ and you are in the muskeg . . .

“You hear yells all around. ‘Where the devil is that crossing?’

The only way you know there are any buffalo is by the snorts and crashing of brush as they tear through. Then ‘Ker-splash!—you’re in the muskeg . . .

“Where’s the buffalo, the riders and everything, you wonder as you scrape mud out of your eyes and try to encourage your horse to get back on solid ground.

“There’s a crash and a grunt right behind you as a lone old buffalo bull comes in. He looks big so you go right across that muskeg and give him lots of room.

“Out on solid ground again the noise ahead tells you the riders have a bunch and are fighting to hold them from breaking away. Fully 500 buffaloes are running strong and fighting to get away as riders streak here and there trying to hold the milling herd and head them down the drift fence.

“The leaders are heading straight for the gate now, with all the riders spread out in the rear.

‘Well we sure got ‘em now. Maybe—if we can hold ‘em.’

“Part of the bunch go through the gate and the remainder turn and hit for the open spaces. Despite some breakneck riding, part of them get away.

“’Well we got about 400 that time anyway,’ a rider with yellow chaps remarks as he comes up alongside on a sweat-lathered horse. ‘Lots more left for another day.’

“’There’s two buffalo mired back there in the muskeg,’ a rider announces as he lopes up and joins us at the gate. ‘Let’s go back and snake ‘em out.’

“Back in the muskeg, where it has been crowded and trampled into the deep mud, a yearling wallows right up to his neck. A lariat whistles out and lands over its head as a rider circles close.

“A snub of the rope around the saddle horn, a heave as the horse puts his weight on the rope and out he comes. Easy money!

“Further over, struggles and flounders an old cow, just stuck deep enough to hold, but too far out to reach with a lariat. It’s a case of wade in and all hands on the tow line. Gradually, with her eyes a-rolling and snorting vengeance out comes the dear old dame.

“’Snub that line!’ yell the boys on foot as they pass the end of the lariat to a rider and then scatter. For just as soon as the cow hits solid footing she lets out a snort and charges her rescuers. No gratitude there!

“She has to be thrown and the rope taken off. This operation takes nerve as it is a case of slipping the rope, then beating it for your horse before the spiteful cow can get up.

“Let’s high-tail it for camp and dinner. The riders are away in a swirl of dust. Arriving at camp tired, sweaty and sore, you crawl off the horse. Your belt buckle feels up against your backbone and you are hungry enough to eat an ox.

“After dinner, with a smile of complaisance and a cigarette in your mush you wander down to the stable corrals and watch riders saddling up fresh horses for the afternoon work, which consists of putting through the corral chutes the buffalo that you helped run into that mile-square enclosure awhile ago.

“On a fresh horse you ramble up to the corrals with a couple of riders who are taking charge of the big slide gates, when the other riders run the bunch in.

“But you notice broken posts and splintered planks here and there which tells you that something besides the wind has been blowing around here.

“Yells in the distance and a drumming of hoofs tells you that the action has started. Coming into view over a fold in the rough ground half a mile away, you see the buffalo coming on the dead run, with riders darting here and there in the rear, herding, holding and turning the buffalo along drift fences.

Riders—at upper left—bring them in at a fast run, darting here and there, herding, holding and turning the buffalo. Some go in–others break back in every direction.

“As the buffalo near the corral gates, the converging drift fences bunch them into a compact running mass, dust clouds with buffalo and riders all mixed-up. Part go into the corral. Some break back.

“The big gates slide shut with buffalo inside milling. Some charge back at the gate and, landing with a crash, threaten to go through. One hits the side head-on and is hurtled back by the impact with its neck broken.

“Just a spasmodic kick or two and there it lies, dead—rather than submit to being manhandled.

“The others quiet down into a sullen and resentful submission, jumpy and showing fight as riders appear on the corral sides.

“The sweating and heaving saddle ponies are all tied up along the corral, for their part is done. The riders have to get into the corrals with the buffalo and work them afoot. A saddle horse in that corral full of buffalo would not last a minute.

“A man, by keeping on the alert, can always climb out of the way when a buffalo takes after him—though he wants his jumping apparatus in first-class condition.

“With 100 or so in the corrals the cutting out starts. From there on into the chutes one at a time.

“If it’s a beef animal it is released into the beef enclosure where it is held until butchers are ready for it.

“The others are let right through the chutes after being checked for the annual herd census into a 16-square mile enclosure until after roundup.

“That night, back at the bunk house with the riders, a full supper under your belt and the old pipe smoking just right, the excitement of the day is still with you and you want to hear more about this ‘Buffalodom.’

“Now anybody can ride—but to hit the saddle day after day, sunshine and rain, requires more than that. We all rode for wages, yet if that was all we rode for, those old roundups would have been riderless.

“It was for the love of the game and the horses that kept us at it—when hambones were weary and knees felt like lumps of lead. It was the creak of saddle leather, a horse and the lure of the open range that got a fellow—and he stuck!

“So stranger, dawn comes early in range land. Let’s hit the blankets, for there’s still over 6,000 buffalo roaming the hills tonight that we have to corral during the next few weeks.

“Sport? Sure you’ll get lots of it—saddle blisters too—if you ride with the Buffalo Park roundup crew!”

Closing out the Wainwright Herd

In 1925, 1,625 buffalo were shipped out to Wood Buffalo Park. Then for the next four years about 2,000 head made the 700-mile rail and water trek to Great Slave Lake.

For 4 years some 2,000 buffalo travelled 700 miles each year by water and rail to a new home at Great Slave Lake. This photo shows the stockyards where buffalo were loaded onto boats for part of their trip.

The first shipments were branded with ‘Gamb Joint W’ brand. The ‘W’ brand provided identification so that northern game wardens could distinguish the Wainwright buffalo from their own herd. They branded 1,634 head before protests from the SPCA forced them to discontinue branding.

“In 1938 command was received from Ottawa that the Wainwright Buffalo Park Reserve was to be cleared of all animals—to become a National Defense Area,” recalls Cotton.

The pasture was deemed ideal for a military practice range. The buffalo had to go.

In 1945-46, the Camp was used as a prisoner of war facility where over 1,000 German Officers were interned.

“In all the 6,673 head of buffalo they shipped north still holds the record as being the largest movement of wildlife ever undertaken by rail and water.

“Others were rounded up and slaughtered. And the remaining gallant animals that couldn’t be corralled were shot as they roamed the plains.

It was wartime in Europe—time for war preparation in Canada.

“The round-up continued all winter and by spring of ’40 the Battle River Valleys became deserted range lands, void of all animals.

“In the peak years in Buffalo Park we were handling over 8,000 buffalo through the corrals. Two thousand was the record of the annual slaughter through the processing plant. Other years from 1200 to 1600 were cut out for beef and hides.

By 1940 over 40,000 Great Plains Bison were produced and shipped from Buffalo National Park all over North America, Europe and Asia.

“Sam Purshell was our sharpshooter and undoubtedly holds the world’s record with an estimated 39,000 buffalo shot. Sam’s job was a real tough and cold one. Ten to 40 below, he was out in the beef enclosure averaging 50 to 80 animals a day to keep the slaughter house crew busy.

“The buffalo riders too hold a record! Through corrals over 48,000 buffalo were checked through on 19 roundups. In addition to branding 1,634 of the 6,673 shipped north, 60 head of buffalo heifers were dehorned for a special assignment.

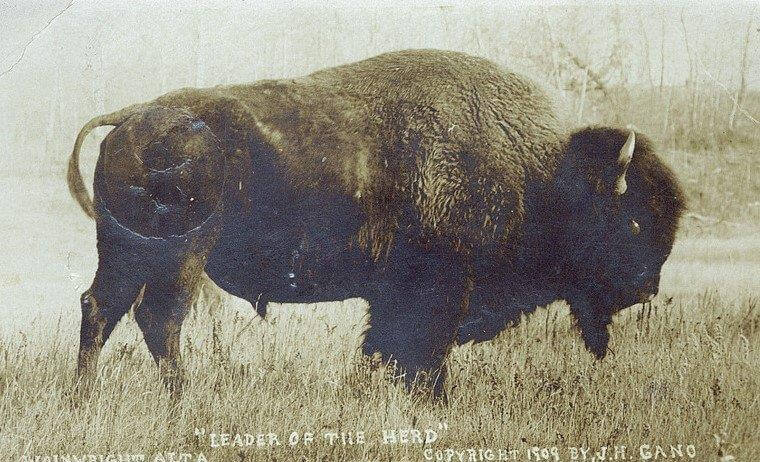

“For 30 years the buffalo had again trod the old trails and dug out the sand-filled wallows of their ancestors. The Battle River hills rumbled again with the thunder of mating bulls in mid-summer.

Battle River hills rumbled once again with the thunder of mating bulls in mid-summer for the Leader of the Herd. Now it’s only an illusion for Bud Cotton. Yet he longs to see a faded old buffalo wandering the valleys and sand ridges and looks for him—“Every time I travel over that ridge!” Photo 1909, JH Gano.

“Dust clouds rose from drumming hoofs . . . but now the dust clouds rise as the huge army tanks complete their maneuvers. The Department of National Defense took over on July 1, 1940.

“Allen Treffry rode with us on the roundups for many a year. Later he rode the old Buffalo Range in a jeep for DND.

“Twenty-one years had gone by since we cleared the last buffalo out of the park, but I’ll bet he still looked down in the valleys and sand ridges—hoping to see a buffalo.

“I know I do—every time I travel over that ridge!”

Excerpted from: Saga of the Wainwright Buffalo Reserve, by Bud Cotton, Buffalo Park Warden 1912-1940, from Buffalo Trails and Tales, Wainwright, Alberta, Canada, 1973.

NEXT: Celebrate National Bison Day, November 6, 2021

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog