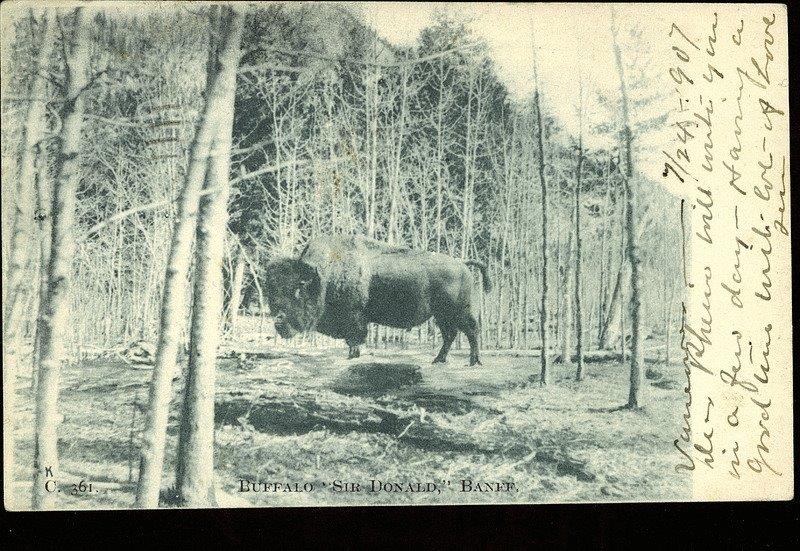

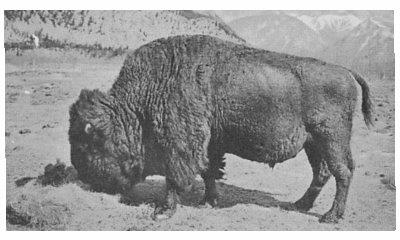

For many years Sir Donald reigned as the dominant bull in the exhibition buffalo herd at Banff National Park in Canada.

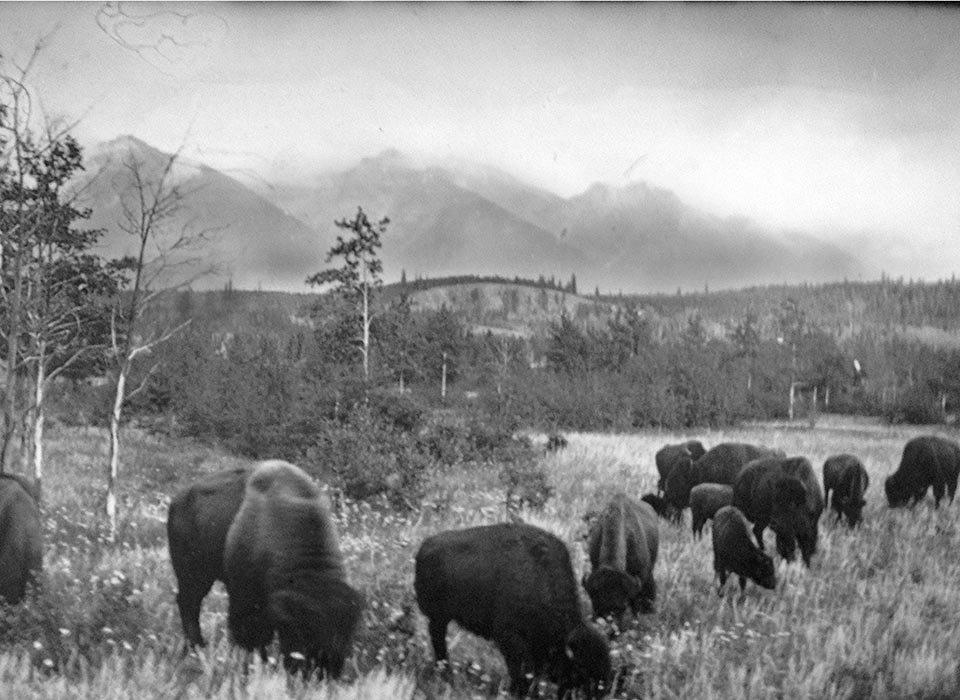

Banff holds the distinction of being not only Canada’s first national park but also the location of its first conservation herd of bison.

The Banff buffalo herd arrived in 1897, with the first gift of three from T. G. Blackstock, a Toronto lawyer, originating with the Goodnight herd of Texas.

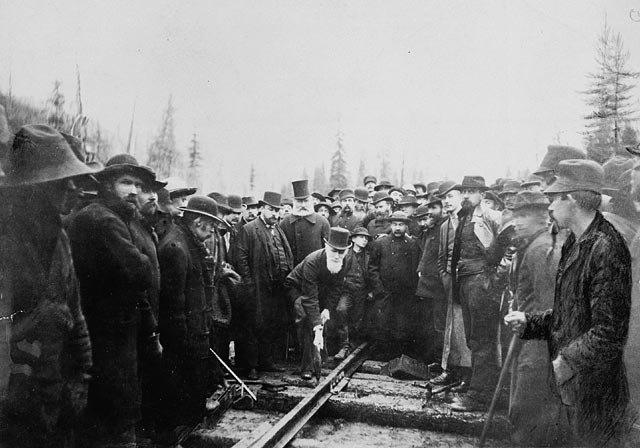

Later 16 Canadian Plains buffalo were donated by Sir Donald Smith, Lord Strathcona, including the bull who became known as Sir Donald, after his donor. Smith was famous in Canada for helping build the Trans-Canada Railway.

By 1899, there were 30 buffalo in the small Banff pasture, all doing well, along with captive elk, moose, deer, goats and Bighorn sheep.

The Banff buffalo herd grazed in a 300-acre paddock. Since it was a small enclosure, and the herd increasing in size, they were fed hay and supplements as needed.

In 1907 Canada purchased the Pablo Buffalo Herd from the western plains of Montana. Banff received 77 of these animals, and a new paddock of 300 acres was built north of the railroad to hold the increasing herd.

Sir Donald was a handsome bull. It was said he represented well the ideal that Native hunters preferred—a bull with well-built forequarters and large head.

Featured on many postcards, Sir Donald’s photo was mailed around the world by tourists who visited the popular new park at Banff.

A familiar sight for tourists, Sir Donald was featured on many picture postcards.

According to one news report, “He answered best to the Indians’ description of the buffalo, being short and very thick and deep in the body, with an extremely massive head. . . And he was undoubtedly a really pure-bred bison.”

Another well-known buffalo in the herd was Highland Mary, an early daughter of Sir Donald’s. A smaller “bright-colored” buffalo, she was also recognizable and known to visitors.

Grand specimen of the breed that he was, when fully-grown Sir Donald’s head measured 49 inches from tip to tip of his horns, and 15½ inches between the eye sockets across the forehead, according to reports.

His horns were 18½ inches long, with a girth around of 14½ inches.

Sir Donald’s Origins

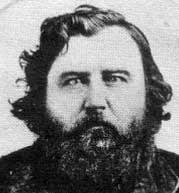

Known as the “Last Wild Buffalo in Captivity,” the famous Sir Donald was rescued from the wild in a Métis buffalo hunt by James “Tonka Jim” McKay and friends of Winnipeg, Canada.

Tonka Jim McKay rescued the calf later known as Sir Donald, reportedly from a Métis hunt in the Battleford area of Saskatchewan in 1872.

Reportedly, he came from the Battleford area of Saskatchewan around 1872.

McKay, a Métis interpreter at the Numbered Treaties and hunting guide, began rescuing young calves because of his concern that each time he joined the semi-annual Métis hunt there were fewer and fewer buffalo on the Canadian Plains. He did not want them to die out.

Although one report has it that Sir Donald was rescued as a 2-year-old bull on the western plains of Canada, it’s much more likely—as in other reports—that he was captured as a young calf.

That was McKay’s normal style— to save young calves in a hunt—as with the others of his growing herd. At his home ranch near Winnipeg, he “mothered up” the calves with dairy cows until they bonded.

Capturing and taming a nearly full-grown buffalo might sound easy to those who hadn’t tried it, but was extremely difficult to accomplish successfully. Older bison when roped often fought viciously. Many simply lay down and died.

By contrast, young calves certainly required careful attention to nutrition—they needed rich milk and quickly—but when handled carefully, and coaxed with a willing milk cow, they tended to bond well with their nursing mothers.

McKay’s style was to capture young calves during a Métis hunt, then “mother up” the calves with gentle cows until they bonded at his home ranch near Winnipeg. Photo by Chris Hull.

When Tonka Jim McKay died in 1879 his herd of 13 buffalo were auctioned off at a well-attended sale. They were purchased by Samuel Bedson, warden of the Stony Mountain Federal Penitentiary near Winnipeg for $1,000.

Since he was short of money, Bedson borrowed part of it on that day from Sir Donald Smith, also known as Lord Strathcona.

Near the prison Bedson had built a pen for his bison herd. Locals called this enclosure “the Castle,” and its owner, “King of the Castle.”

As a side note: One of Bedson’s new cows gave birth just after the auction and the newly-enlarged herd of 14 was driven by cowboys to their new home at the penitentiary.

They escaped in the night, were rounded up and returned to their new home.

It was recorded that the little newborn calf kept up with the herd for the entire journey—a total of 63 miles in 36 hours—averaging nearly two miles per hour.

Originating in the western Plains of Canada, the little tyke was hailed as being of hardy Canadian stock!

The herd was kept at the Penitentiary near Winnipeg, soon growing to the unmanageable size of 118 head. Some were given to Sir Donald Smith as pay back for Bedson’s initial debt.

In turn, Sir Donald Smith donated some of these—including the bull later named for him—to the display herd at Banff.

The man with the long white beard is Lord Strathcona, Sir Donald Smith. He is here depicted driving in the last spike of the Trans-Canada Railway, in perhaps one of the most famous photographs of Canadian history. Sir Donald Smith helped stitch the country of Canada together with the railway, but beyond his industrial actions, he had an interesting role to play in the early history of bison conservation. Photo taken 7 November, 1885 at Craigellachie, B.C. Archives Canada.

The large bull known as Sir Donald became the dominant bull in the popular herd near the visitors’ Center at Banff.

“A grand specimen of the breed” Sir Donald measured about 49 inches from tip to tip of the horns, and 15½ inches between the eye sockets across the forehead. “The remaining horn is 18 ½ inches long and its girth is 14½ inches. Short and very thick and deep in the body, with an extremely massive head in front. . . undoubtedly a really pure-bred bison.”

As the most powerful bull in the herd, Sir Donald fought many bulls over the years to establish and defend his place at the top of the hierarchy.

End of Sir Donald’s Reign

The fight that finally took Sir Donald down at age 33 was described in a news story as “a terrific battle for supremacy between him and a young bull of almost equal size imported from Texas.

“The fight began early in the morning, the great heads lowered and little red eyes glaring, tearing up the turf with their hooves, and with tails straight up in the air. With the crash like colliding engines they met over and over again.

“Several mounted men endeavored to separate the infuriated animals, but were themselves charged and put to flight.

“Sir Donald at last lost his left horn in one of the shocks, at the same time getting a blow in the left eye which destroyed its sight.

“After being thrown on his back and pummeled while down by his victorious challenger, he gave up the struggle and retired from the gaze of the watching herd to begin his lonely wanderings.

“Since that time he has seldom been seen with the rest, preferring to wander and wallow alone in some favorite sand hole.”

A Retirement of Lonely Wanderings

Sir Donald’s lonely wanderings lasted 5 years during which the herd largely ignored him.

Although still in one of the small paddocks, he stayed some distance from the herd.

As he began to feel his age, the Commissioner of Canadian parks Howard Douglas, of Banff, announced that this last of the known buffalo survivors of the immense herds which used to roam the plains of the Canadian west, “Sir Donald . . . will within a few weeks be put to death, and later mounted” in full-size to be placed in a museum.

On March 12, 1909, The Wainwright Star at Wainwright, Alberta, reported:

“This veteran bull still grazes with the ancient bulls of the herd at Banff, but he has long since been driven out from the main body by the younger bulls.

“Lately he has shown such signs of age that the authorities have decided to end his career, not only out of mercy to himself, but to keep his hide and fur intact for exhibition purposes.

“Sir Donald is the only living buffalo in captivity who ever roamed the prairies of Canada with the aboriginal herds.

“He was captured in 1872, as a calf, by the late Hon. James Mackay, who was a noted figure in the early history of Manitoba and the Canadian west.

“Mr. Mackay was collecting a herd for his private ranch, and captured the calf amongst a dozen others. The herd was kept at Silver Heights, near Winnipeg, for a number of years, and later transferred to Warden Bedson of the Stoney Mountain penitentiary, with whom Lord Strathcona had considerable interest in the preservation of the buffalo.

“Sir Donald Smith on the division of the herd, presented this bull with 12 other buffalo, to the dominion government and they were sent to the national park at Banff, where they became the nucleus of the present herd of about a hundred animals.”

About a month before his death, the Commissioner Howard Douglas had gone out with a local taxidermist to the paddocks to inspect him.

But at that point, the old bull seemed quite lively. In fact, Sir Donald charged vigorously at his distinguished visitors, They escaped outside the fence.

This seemed to indicate plenty of reserve strength in his body, despite the fact he had lost his left eye and left horn in his last desperate fight.

So again Sir Donald was allowed to wander away from the herd—which was in a rather small pasture.

Then came news of his death.

The cowboy in charge of the paddocks saw Sir Donald walking around at five o’clock on a Monday afternoon, and on looking for him next morning saw that he was down and apparently dead.

He covered the carcass with tarps to keep it safe from the prowling wolves and coyotes.

Steps were taken at once to return the taxidermist Ashley Hine to the paddock.

Trampled and Gored to Death

Then a number of the park workmen came with a large sleigh to move the body to the Sign of the Goat taxidermy shop.

But it was too late. The herd had returned, were attacking the carcass, and could only be driven away with great difficulty by the buffalo handlers.

Each bull seemed determined to make one last goring of the remains with his horns.

There was nothing left of the body but a mass of jellied flesh, hair and blood. Only the head and four legs were recognizable.

One newspaper headlined the story: “Old Sir Donald, the Patriarch of the American Bison, Trampled and Gored to Death in Corral at Banff.”

“Many thousands of visitors to Banff, the delightful resort in the middle of the Canadian National park, had seen and admired the grand old buffalo bull, Sir Donald, who had been the leader and chief of his herd for upwards of 38 years.

“But never again will the grand head and massive proportions of this animal, the only really wild bison in captivity, be viewed in their natural environment, for during the early hours of Tuesday morning, April 6 (1909), old Sir Donald came to his final end.

“He was found lying dead out in one of the paddocks, having apparently stumbled over some bogs, probably owing to his being blind in one eye, and while unable to rise he was surrounded by the rest of the herd.

“Alas, for respect among the bison some of the younger bulls took the opportunity to help him onto the happy hunting grounds by goring the huge beast with their short and sharp horns.

“Not content with this, the herd pawed and butted at the prostrate monarch till, except on the head and the legs, there was no hair left.”

Photographers attempted to shoot pictures of him “as he lay in his last sleep,” while trying to keep away from the most aggressive buffalo.

As the workmen with the sleigh tried to load what was left of the carcass, the herd kept closing in, forming a compact half circle around them.

The horses pulling the sleigh got very alarmed, and only expert action on the part of drivers prevented a runaway.

“Highland Mary, a small bright colored cow buffalo, a very early daughter of the dead bull, was the most aggressive, coming within 12 or 15 feet of the workers. But as she was nearly as old as Sir Donald, she was treated with the respect she deserved.”

It took several hours to get the hide off, which was in some places 2 inches thick.

Finally the workmen finished and got the remains loaded onto the sleigh, with the head hung from the back, for the trip back to town. Most of the men took a short cut over the fence for home.

But here the herd again took a hand.

As the sleigh came closer the buffalo charged up to it, crowding each other to get near the head hanging from the back.

“Three times the driver of the team fell over obstacles before he reached the gates, having to keep his eyes on his frantic horses and on the bellowing herd behind him.

“His companion proceeded to open the gate, and for a few moments it looked as if the whole herd would escape into the adjoining paddock.”

Luckily the two men were able to chase back the buffalo that got out and close the gate.

“The head of Sir Donald is now in the hands of the government taxidermist, and will eventually adorn the walls of the museum in Banff.”

Reflecting on the attack

In summing up, how are we to regard the violent and vicious attack of the young bulls against their former chief?

What do we tell the children?

The buffalo herd’s treatment of a former leader sounds harsh, but it is a part of nature, which as we know, can turn savage and ruthless.

Stark beauty of Lake Moraine near Banff. Even in the midst of stunning beauty, nature can be cruel and harsh, unforgiving of weakness.

And how can we deny, as we read history of the world—even at its most “civilized”—the examples of once-powerful human rulers cut down at the end of their reign in violent and vengeful ways—even by their own sons or nephews just as Sir Donald was?

Those of us today who live in peaceful democracies can be grateful that our former leaders generally are treated with dignity and respect.

Whether we agreed with them or not in their power, once deposed we retire them in peace and allow them to hold onto self-respect with their gilded libraries, autobiographies and memoirs, their speeches and harmless hobbies of painting and riding their gentle, old horses.

We don’t stomp on them, tear them to shreds—imagine! Even though some cruel dictatorships seem almost to ask for it and indeed it is literally the way they end.

It’s exactly how these blood-thirsty young buffalo bulls finished off their erstwhile leader Sir Donald at age 38! Fortunately, he first had 5 years of peaceful, if lonely, retirement when he was allowed to wander off alone!

But a peaceful end was not in the cards with Sir Donald’s vengeful heirs waiting in the wings in their small paddock.

They followed him down in the bog, unable to rise. In his humiliation, he had only one working eye and one horn for defense. And they attacked, knowing he had lost all power over them.

Instead of the full-body-mount and honor his handlers had planned for Sir Donald, only his head was left intact—with a missing horn.

His massive head was mounted and hung in the office of the Park Commissioner—presumably with two glass eyes and one remodeled horn.

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog

Thank you for documenting the buffalo. I enjoy your stories, and I love the idea that Hettinger was part of their history. I was born and raised in Hettinger, and I believe you might have known my mother, Virginia Page. Thank you again for your wonderful stories, keep writing.

Yes Marilyn, I was acquainted with your mother Virginia. It’s been quite awhile though. Glad to have you aboard! Best wishes, Francie

Yes Marilyn, I was acquainted with your mother Virginia. It’s been quite awhile! Glad to have you aboard! Best wishes, Francie

How very sad for Sir Donald, but as you say, sometimes nature can be cruel.

I am finding your articles in your blog extremely interesting. I had no idea that the Canadian Government purchased buffalo from the U.S. Interesting also to note that they still roam free in Banff National Park.

Yes, I think many Canadians were shocked to learn their Plains buffalo were gone at the end. And they bought many more than they’d bargained for from Pablo–and paid handsomely for them. But I think they were happy. And the remnants saved at Banff actually had a Canadian history. And now they have a wild herd roaming free there!!

Amazing history isn’t it? I hope sometime you get to see them.

Francie