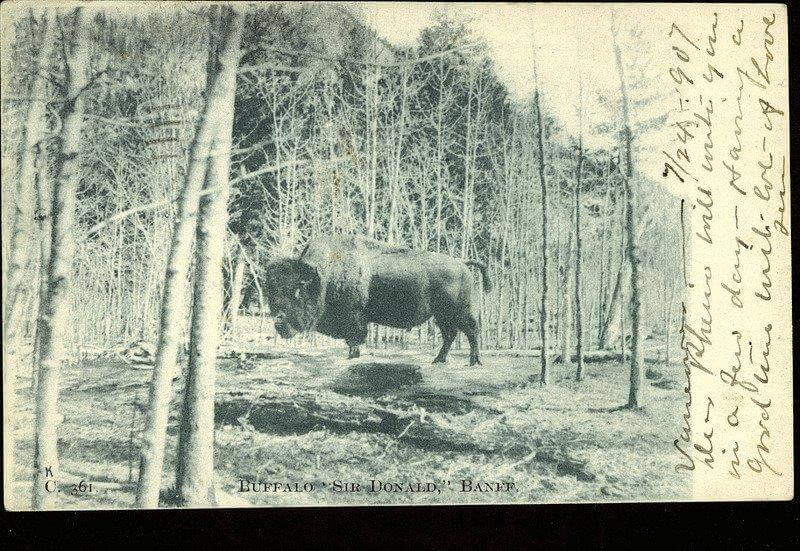

Featured on many postcards, Sir Donald’s photo was mailed around the world by tourists who visited the popular new National Park at Banff. Photo Parks Canada.

The Banff buffalo had a dramatic history. And the most famous buffalo of all was Sir Donald, named for his donor Sir Donald Smith, Lord Strathcona.

Smith was famous in Canada for helping build the Trans-Canada Railway.

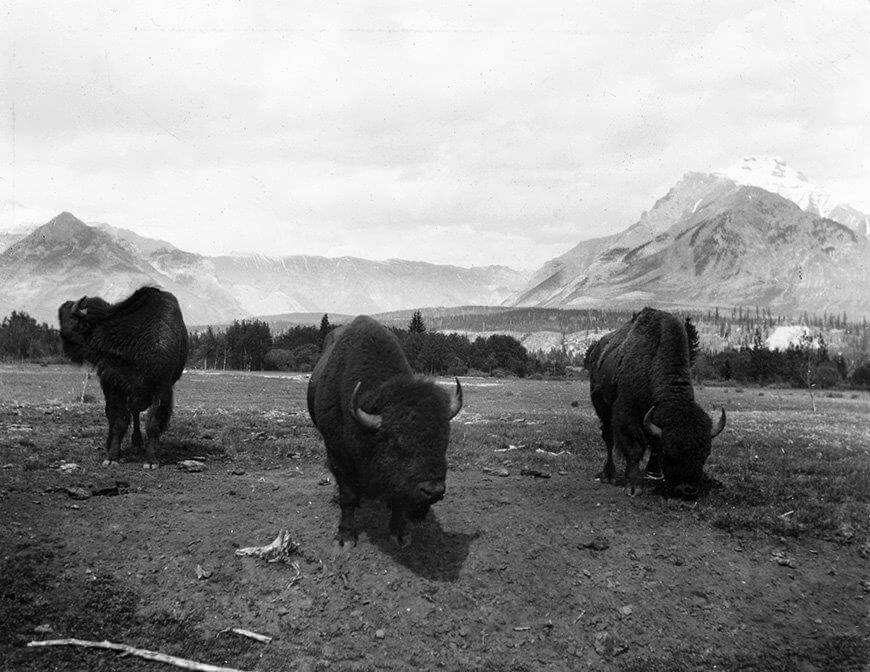

Plains buffalo have been in Banff National Park almost from the beginning—in a small pasture by the main line of the Canadian Pacific Railroad.

They became famous with tourists and lived there in a display herd along the new railroad for nearly a century, from 1897 to 1997.

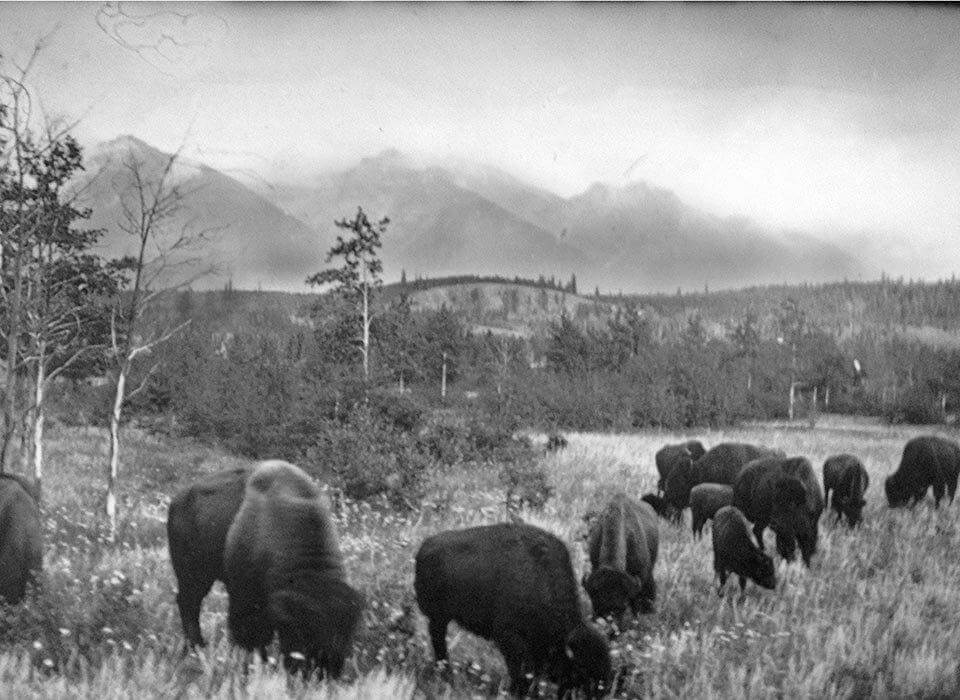

In 1907 the Canadian government—suddenly realizing they were bereft of buffalo—purchased the Pablo Herd of over 700 from the western plains of Montana.

Banff received 77 of these animals, and a new paddock of 300 acres (only!) was built north of the railroad to hold the increasing herd.

How Banff National Park Began

It was a time of railroad building. The Canadian Rails had a major challenge—to link the busy Pacific Coast area, with all its ships filled with Asian produce and returning with high quality timber, with the rest of Canada.

In between stood hundreds of miles of spectacular—but nearly impassable Rocky Mountains. Icy and often snow topped, these rugged mountains are just north of US Glacier Park. Which are also formidable lands, filled with huge glaciers, ice and rocks.

During the 1870s, construction started on the ambitious Canadian Pacific Railway, a coast-to-coast railway across Canada. The planned route tracked through the Bow Valley in the Canadian Rocky Mountains.

On October 21, 1880 a group of Scottish Canadian businessmen formed a viable syndicate to build a transcontinental railway.

Many of the workers in the tracklaying crew were immigrants from Europe; many others were Chinese.

Often up to 200 men would be working together to move the track forward and many of them lost their lives laying track in those icy mountains.

Construction began on several fronts.

It was there, at ‘Siding 29,’ that three Canadian Pacific Railway workers in 1883 stumbled on a series of natural hot springs on what is now called Sulphur Mountain.

The Cave and Basin hot springs were quickly identified as potential hot tourist attractions.

By the end of 1883, the railway had reached the Rocky Mountains, just eight kilometres (five miles) east of Kicking Horse Pass.

Competing claims by ‘discoverers’ of the springs for the right to develop them prompted the Canadian government in 1885 to create a reserve to protect the hot springs and surrounding area.

Enlarged in 1887 and named the “Rocky Mountains Park of Canada” (later to be renamed Banff National Park), this was Canada’s first national park and the world’s third.

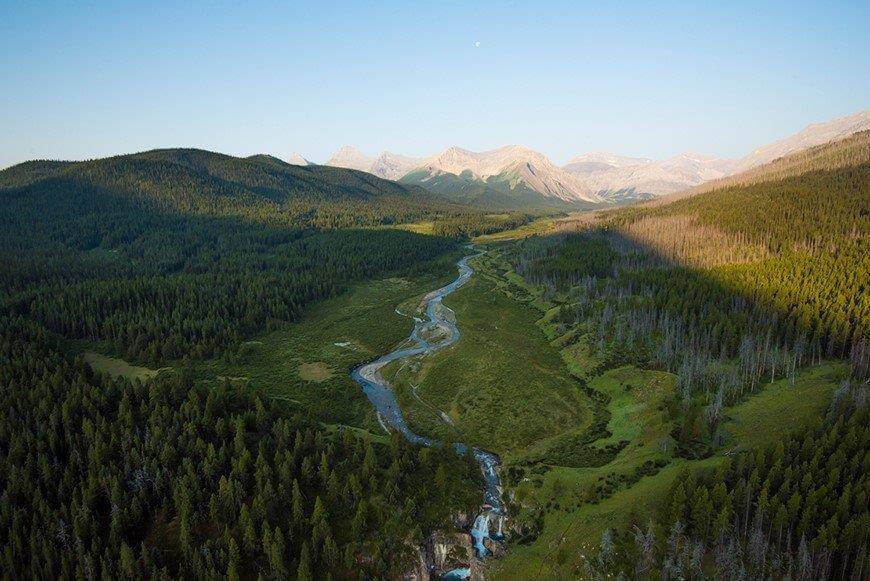

The park now occupies 2,564 square miles (6,641 square km) along the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains and abuts the border with British Columbia.

The townsite of Banff was established; a grand hotel quickly built, and the area was soon promoted as an international resort and spa.

In Canadian history, four provinces joined together on July 1, 1867, to form the new country of Canada. The four provinces—Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Quebec and Ontario—were joined three years later by Manitoba and the Northwest Territories.

In 1871 British Columbia decided to join Canada, but only if the Canadian government promised to build a transcontinental railway.

British Columbia set a 10-year deadline for the completion of this critical link to the rest of the country.

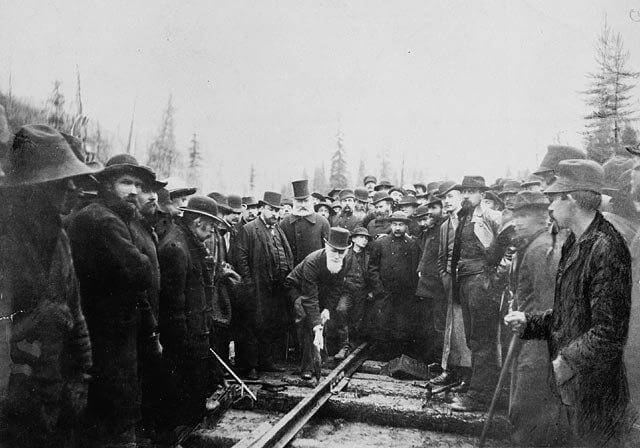

But this incredible engineering feat was completed on Nov 7, 1885, six years ahead of schedule, when the last spike was driven at Craigellachie, B.C. The rest, is history.

The man with the long white beard is Lord Strathcona, Sir Donald Smith. He is here depicted driving in the last spike of the Trans-Canada Railway, in perhaps one of the most famous photographs of Canadian history. Photo taken 7 November, 1885 at Craigellachie, B.C. Archives Canada.

Sir Donald Smith helped stitch the country of Canada together with the railway, but beyond his industrial actions, he had an interesting role to play in the early history of bison conservation.

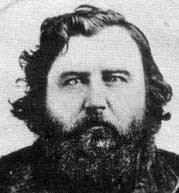

McKay: A Métis who Saved Calves

The Banff buffalo herd arrived in 1897, with the first gift of three—1 bull and 2 females—from T. G. Blackstock, a Toronto lawyer, who obtained them from the Texas herd of Charles Goodnight.

Soon after came 13 genuine Canadian Plains Buffalo that originated from calves rescued by James McKay and friends of Winnipeg.

A Métis leader, McKay had often joined the large semi-annual Métis hunts in the Plains of western Canada and into Montana.

He was celebrated as one of the five people who rescued calves—the only Canadian. Perhaps because the big Métis hunting parties had swept Canada bare of Plains buffalo. There were no buffalo left to save.

Living near Winnipeg, Canada, Tonka Jim McKay began his career working for the Hudson Bay fur trading company, as did his Scottish Highlander father. His mother, Margarete, was Métis.

James McKay, a Métis fur trader, became a politician, translator and guide. During the big Métis buffalo hunts, worried at the scarcity of buffalo, he began rescuing young calves. Photo Parks Canada.

McKay served as postmaster and clerk, managed small trading posts mostly in what are now southwestern Manitoba and southeastern Saskatchewan and established two Hudson Bay posts in US territory.

Moving into Manitoba politics, he represented the Métis people and helped them negotiate treaties. He served Manitoba as president of the Executive Council, Speaker of the Legislative Council and Minister of Agriculture.

With his knowledge of the prairies and indigenous people, McKay also excelled as a frontier interpreter and guide.

Often McKay wore the popular Métis attire—a hooded blue capote with pants of homemade wool, moccasins and a colorful sash.

McKay’s style was to capture young calves during a Métis hunt, then “mother up” the calves with gentle cows until they bonded at his home ranch near Winnipeg. Photo Parks Canada. Parks Canada.

Tonka Jim McKay rescued the calf later known as Sir Donald, reportedly during a Métis hunt in the Battleford area of Saskatchewan in 1872. Glenbow Archives.

McKay became alarmed at the scarcity of buffalo. With each hunt, he noted his friends were going farther west and south into Montana with their Red River Carts to find buffalo herds, which became scarcer and scarcer with each big hunt.

On an 1873 Métis hunt he captured three young calves with the help of friends and the next year, another three, bonding them with nurse cows on his Deer Lodge ranch some 28 miles west of Winnipeg.

He purchased a few more calves from Métis hunters who went west to hunt and returned through Winnipeg.

In about 1877 McKay sold five calves to Colonel Sam Bedson, a penitentiary warden, for $1,000. Bedson’s buffalo thrived. By 1888 he owned nearly 80 full-breed buffalo and 13 half-breeds.

Unfortunately, in 1879, just as his buffalo herd was gaining some natural increase, Tonka Jim McKay died at the age of 51.

After his death some of McKay’s buffalo went to the Canadian government. But 13 went to a neighbor who then donated all his 13 buffalo to Rocky Mountain Park in Banff for that special exhibition herd.

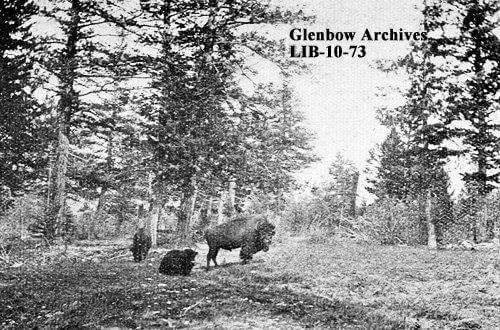

Exhibition herd in paddock at Banff National Park, Alberta. Glenbow Archives..

The successful rescue of buffalo calves happened in only five known places in the north American hemisphere—at a time when the species was nearly exterminated by hide hunters.

The five families were able to catch newborn or young buffalo calves, nurture them with range cows or the colostrum that newborns needed to survive and raise them into a viable herd—with enough numbers to ensure herd survival.

The rescuing families were:

- James McKay and friends in Manitoba, Canada;

- Samuel Walking Coyote and herd purchasers Charles Allard and Michel Pablo in western Montana;

- Pete Dupree, Fred Dupris and herd purchasers, the Scotty Philips in South Dakota;

- Charles and Molly Goodnight of Texas;

- CJ (Buffalo) Jones of Kansas.

Separately, these people brought buffalo back in significant numbers—onto the western plains and grasslands where they have always thrived so well.

They were ordinary people—westerners, ranchers, even buffalo hunters—with boots on the ground. Or more specifically, in over half the cases—moccasins on the ground.

Most realized buffalo were rapidly disappearing and did what they could to help.

The first three had Native American roots: James McKay in Manitoba, Canada, Samuel Walking Coyote and herd purchasers in Western Montana, the Duprees (with their father Fred Dupris and Scotty Philip (herd purchaser) in South Dakota.

Sir Donald Spikes Tourism

Reportedly, McKay rescued Sir Donald in the Battleford area of Saskatchewan around 1872.

Although one report has it that he was rescued as a 2-year-old bull on the western plains of Canada, it is much more likely—as in other reports—that he was captured as a young calf.

That was McKay’s normal style—saving young calves in a hunt—as had been the others of his growing herd. At his home ranch near Winnipeg, he ‘mothered up’ the calves with dairy cows until they bonded.

Capturing and taming a nearly full-grown buffalo might sound easy to those who haven’t tried it, but was extremely difficult to accomplish successfully.

Older bison when roped often fought viciously. Many simply lay down and died, apparently of a heart attack.

By contrast, young calves certainly required careful attention to nutrition—they needed rich colostrum milk and quickly—but when handled carefully and coaxed with a willing milk cow, they tended to bond well with their nursing mothers.

When Tonka Jim McKay died in 1879 his herd of 13 buffalo were auctioned off at a well-attended sale. They were purchased by Samuel Bedson, warden of the Stony Mountain Federal Penitentiary near Winnipeg for $1,000.

Since he was short of money, Bedson borrowed part of it on that day from Sir Donald Smith, also known as Lord Strathcona.

Near the prison Bedson had built a pen for his bison herd. Locals called this enclosure ‘the Castle,’ and its owner, ‘King of the Castle.’

As a side note: One of Bedson’s new cows gave birth just after the auction and the newly-enlarged herd was driven by cowboys to their new home at the penitentiary.

They escaped during the night, fled back to familiar home ground, then next morning were rounded up again and returned to their new home.

It was recorded that the little newborn buffalo calf kept up with the herd for the entire journey—a total of 63 miles in 36 hours—averaging nearly two miles per hour for a day and a half!

Newborn calf of ‘hardy Canadian stock’ traveled 63 miles in 36 hours, keeping up with the herd, averaging nearly two miles per hour. Parks Canada.

Originating in the western Plains of Canada, the little tyke was hailed as being of ‘hardy Canadian stock!’

The herd was kept at the Penitentiary near Winnipeg, soon growing to the unmanageable size of 118 head. Some were given to Sir Donald Smith as pay back for Bedson’s initial debt conservation.

A Handsome Bull: Winner of Many Battles

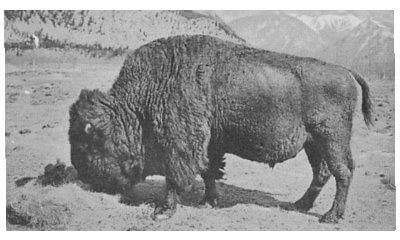

Sir Donald was said to represent the ideal that Native hunters favored. With huge forequarters and head, and smaller hips. Glenbow Archives.

Sir Donald was a handsome bull. It was said he represented well the ideal that Native hunters preferred—a bull with well-built forequarters and large head.

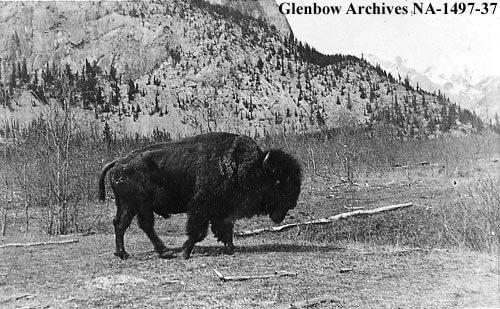

The big bull known as Sir Donald became the dominant bull in the popular herd near the visitors’ Center at Banff.

Known as the ‘Last Wild Buffalo in Captivity,’ the famous Sir Donald was apparently rescued from the wild in a Métis buffalo hunt by James ‘Tonka Jim’ McKay and friends of Winnipeg, Canada.

He was hailed as the last of the great wild herds

Many tourists purchased Sir Donald postcards and mailed them throughout the world.

“A grand specimen of the breed,” he was called. The build that Native Americans admired most in a buffalo bull.

As the mightiest bull in the herd, he fought many battles over the years to establish and defend his place at the top of the buffalo pecking order.

For some 33 years Sir Donald reigned as supreme.

Then he was bested by an equally large young Texas bull.

“The fight began early in the morning, the great heads lowered and red eyes glaring, tearing up the turf with their hooves and with tails straight up in the air. With a crash like colliding engines

they met over and over again,” it was reported.

“Several mounted men endeavored to separate the infuriated animals, but were themselves charged and put to flight.

“Sir Donald at last lost his left horn in one of the shocks, at the same time getting a blow in the left eye which destroyed his sight.

“After being thrown on his back and pummeled while down by his victorious challenger, he gave up the struggle and retired from the gaze of the watching herd to begin his lonely wanderings.

Even after he lost one horn and an eye, it was said, “Short and very thick and deep in the body, with an extremely massive head in front. . . undoubtedly a really pure-bred bison!

“The remaining horn is 18½ inches long and its girth around is 14½ inches. Grand specimen that he was, when fully-grown, Sir Donald measured about 49 inches across the widest part of his horns and 15½ inches between the eye sockets across the forehead.”

Another well-known buffalo in the herd was Highland Mary, an early daughter of Sir Donald’s. A smaller ‘bright-colored’ buffalo, she was easily recognized and well known to visitors.

A Retirement of Lonely Wanderings

The fight that finally took Sir Donald down was described in a news story as “a terrific battle for supremacy between him and a young bull of almost equal size imported from Texas.” Glenbow Archives.

“Since that time he has seldom been seen with the rest, preferring to wander and wallow alone in some favorite sand hole.”

Sir Donald’s lonely wanderings lasted 5 years during which the herd largely ignored him.

Although still in one of the small paddocks, he stayed some distance from the herd.

As he began to feel his age, the Commissioner of Canadian parks Howard Douglas, of Banff, announced that as this last of the known buffalo survivors of the immense herds roamed the plains of the Canadian west, “Sir Donald . . . will within a few weeks be put to death, and later mounted” in full-size to be placed in a museum.

On March 12, 1909, The Wainwright Star at Wainwright, Alberta, reported:

“This veteran bull still grazes with the ancient bulls of the herd at Banff, but he has long since been driven out from the main body by the younger bulls.

“Lately he has shown such signs of age that the authorities have decided to end his career, not only out of mercy to himself, but to keep his hide and fur intact for exhibition purposes.

“Sir Donald is the only living buffalo in captivity who ever roamed the prairies of Canada with the aboriginal herds.

“He was captured in 1872, as a calf, by the late Hon. James McKay, who was a noted figure in the early history of Manitoba and the Canadian west.

“Mr. McKay was collecting a herd for his private ranch, and captured the calf amongst a dozen others. The herd was kept at Silver Heights, near Winnipeg, for a number of years, and later transferred to Warden Bedson of the Stoney Mountain penitentiary, with whom Lord Strathcona had considerable interest in the preservation of the buffalo.

“Sir Donald Smith on the division of the herd, presented this bull with 12 other buffalo, to the dominion government and they were sent to the national park at Banff, where they became the nucleus of the present herd of about a hundred animals.”

About a month before his death, the Commissioner Howard Douglas had gone out with a local taxidermist to the paddocks to inspect him.

At that point, the old bull seemed quite lively. In fact, Sir Donald charged vigorously at his distinguished visitors, and they hastily scrambled over the high fence.

This seemed to indicate plenty of reserve strength in his body, despite the fact he had lost his left eye and left horn in his last desperate fight.

So again Sir Donald was allowed to wander away from the herd—which was unfortunately in a rather small pasture with little chance of escape from raging young bulls.

Then came news of his death.

The cowboy in charge of the paddocks saw Sir Donald walking around at five o’clock on a Monday afternoon, and on looking for him next morning saw that he was down and apparently dead.

He covered the carcass with tarps to keep it safe from prowling wolves and coyotes.

Steps were taken at once to bring the taxidermist Ashley Hine into the paddock.

At this time I won’t go into the details of what actually happened. Let’s just say that it was not a happy ending for Sir Donald.

Some newspapers of the day reported simply that Sir Donald died in a stampede.

That wasn’t exactly what happened. Let’s just say that the details of his death and final tribute are distinctly gory, perhaps considered too much for casual readers at the time.

One newspaper headlined their story: “Old Sir Donald, the Patriarch of the American Bison, Trampled and Gored to Death in Corral at Banff.”

I did quote at length from that paper in my early blog titled: ‘The Sad Demise of Sir Donald,’ which also reported:

“Many thousands of visitors to Banff, the delightful resort in the middle of the Canadian National ark, had seen and admired the grand old buffalo bull, Sir Donald, who had been the leader and chief of his herd for upwards of 38 years.

“But never again will the grand head and massive proportions of this animal, the only really wild bison in captivity, be viewed in their natural environment, for during the early hours of Tuesday morning, April 6 (1909), old Sir Donald came to his final end.

“He was found lying dead out in one of the paddocks, having apparently stumbled over some bogs, probably owing to his being blind in one eye, and while unable to rise he was surrounded by the rest of the herd.”

So I won’t go into it now. Just to reiterate that it was a sad ending for a grand old bull, Sir Donald, reportedly at age 38!

If anyone wants to know more details, they can find them in my early Blog 12, published August 11, 2020.

Seventy-seven buffalo from the Pablo herd were added to the display herd at one time in another 300 acre pasture. Glenbow Archives.

Buffalo Treaty of Co-operation, Renewal and Restoration

Banff has always been a leading actor in the life and death drama of the buffalo.

Since the beginning of time, hundreds of generations of the First Nations of North America have considered the buffalo to be their relatives.

A ‘buffalo treaty’ was signed Sept 23, 2014 on the Blackfeet Territory in Montana, with four additional First Nations signing in Banff, Alberta in August 2015. It’s an agreement of cooperation, renewal and restoration of buffalo on the lands.

“Buffalo is part of us and we are part of buffalo, culturally, materially and spiritually. Our on-going relationship is so close and so embodied in us that Buffalo is the essence of our holistic eco-cultural life-ways.

“It is our collective intention to recognize buffalo as a wild free-ranging animal and as an important part of the ecological system; to provide a safe space and environment across our historic homelands, on both sides of the United States and the Canadian border.

“So together we can have our brother, the Buffalo lead us in nurturing our land, plants and other animals to once again realize the buffalo ways for our future generations.”

The original Buffalo Treaty and resolutions, signed by many First Nations Bands from September 2014 to 2018 are archived at the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies.

A paper published by experts from Parks Canada and the University of Montana says Banff National Park has the capacity for a bison herd to reach more than 1,000.

Marie-Eve Marchand, with the Bison Belong campaign in Banff National Park, says the findings are good news for long term conservation.

“It’s much bigger than we thought,” Marchand told CBC News.

“There’s only a few herds [in North America] over 1,000 and this paper says that Banff could hold over 1,200. We’re looking at the mid-long term before we even get there.

In 100 years how many free-ranging buffalo will live in Banff National Park? Parks Canada.

“I would say it’s probably going to be something for the next generations.”

Future Buffalo Plans for Banff

When the paddock and the bison were removed in 1997 to encourage free flow of wildlife in the Bow Valley area, it was always the stated intention of Parks Canada to return wild bison to Banff to replace the Display Herd.

But it took 20 years. Even though First Nations people and conservationists campaigned continually to get that to happen sooner.

Twenty years of NO Buffalo in Banff—NONE whatever—before the new plan for wild Bison in Banff National Park was deemed ready to be implemented.

Parks Canada now has collected a great wealth of scientific data to enable them to bring more wild buffalo into the Banff National Park in the very best way.

It will be fascinating to see when, how and if that happens!

NEXT: BUFFALO TRAILS and WALLOWS in HETTINGER ND

_________________________________________________________________________

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog

Congratulations! You never stop!

Great stories that can now be shared with others.

Thank you,

Carol

Thanks Carol. I enjoy them as much as you! Francie

Hello! A quick correction re: copyright. That first postcard of Sir Donald isn’t from Parks Canada – the copyright is held by the original archive, Peel’s Prairie Provinces. The information is here: https://archive.org/details/PC010047

Their images are free to use for non-profit, educational purposes but only if they credit the source!

Hi Lauren

I think the 1907 copyright has expired (after nearly 120 years), but you are right. This was in a postcard collection with a group of historic photos available from Parks Canada.

But we always intend to give credit to the source when possible. So the original source was Peel’s Prairie Provinces Prairie Postcard Collection, archived at the University of Alberta Library. Or was it Knowles & CO, London, Ontario?

Best Wishes, Francie