Shadehill Buffalo Jump, 13 miles south of Lemmon, SD, as seen from the north side of Shadehill Lake, which was dammed in the 1950s here where the north and south Grand Rivers come together. A South Dakota Game and Fish sign at left explains archeologists’ recent findings about this buffalo jump. Photo courtesy Vince Gunn.

This is our Hettinger ND/Lemmon SD community’s own Shadehill Buffalo Jump—on the cliff opposite.

This buffalo jump is best viewed from the Shadehill Recreation Area, here on the north side of Shadehill Lake. You can also drive around to the other side and hike above Shadehill Cliff.

As Native tribes grew larger, they discovered a spectacular way to obtain the large quantities of meat they needed—in the communal Buffalo Jump.

Buffalo provided many gifts to the Native people. Everything they needed to live—food, shelter, clothing, medicine, tools, religious icons and much, much more. Every part was honored, right down to the dried manure, used for fuel to warm the tepee in treeless areas.

At the same time, buffalo hunting was a spiritual experience for Plains hunters. They sought divine intervention before, during and after hunts.

Ancient people thanked buffalo daily for their generosity and prayed for them to continue protecting and helping them survive.

The close cultural relationship between the people and buffalo is expressed by John Fire Lame Deer, “His flesh and blood being absorbed by us until it became our own flesh and blood… It was hard to say where the animals ended and the human began.”

Native Americans sometimes explain this as, “You know, the buffalo are our relatives.”

In traditional Plains belief, the buffalo gave themselves willingly as food for Native people. They honored the buffalo as sacred in ceremonies, stories, artwork, song and dance.

Buffalo jumps vary, but all have three parts:

- At the bottom of the jump is a bone pile where an array of artifacts—meaning tools and weapons showing evidence of human involvement—are mixed with buffalo bones and the dust of ages. This tells archaeologists a clear story of what happened here.

- A steep cliff rises above the bone pile—with enough drop to kill or cripple buffalo—this need not be a 400-foot drop, as some imagine. Many successful jumps dropped only 50 or 60 feet before the bone pile began building up, and perhaps 30 feet in its most recent use.

- Above the jump is some kind of plateau with rich grasses where buffalo liked to graze. Here can sometimes be found the drive lines, marked by small rock piles. These are one of the keys to success of the Buffalo Jump.

At one time two layers of buffalo bones were clearly visible on the face of Shadehill Cliff and well known to early settlers in this area. Local folks wondered about the bone site, but they did not claim it as a buffalo jump.

They decorated their flower gardens with buffalo skulls from the jump. School children from the area—including my aunt Margaret Durick Barrett and her sister Dorothy Durick Kroft from White Butte—went to Shadehill on field trips and school picnics to view the bones which “could be a buffalo jump.” Or not, as their teachers told them.

These bone layers were described in 1939 by Archer Gilfillan, local sheepherder and author of the classic book Sheep. He wrote:

South of Lemmon SD, 13 miles to Shadehill and then 3 miles west on a scenic road along the Grand River, is what has become known as the mass buffalo burial. This is a mass of buffalo bones exposed in a steep bank on the south side of the river. The river bank at this point is about 150 feet high.

The bones are in two layers. The first layer 12 feet thick, is about 25 feet below the top of the bank. Beneath this is a 4-foot layer of earth. Then comes a second 4-foot layer of bones, the bottom of which is still 100 feet above the bed of the river.

The two layers of bones are exposed for approximately 100 feet up and down the river. Many of the bones are well preserved, although not fossilized.

Shadehill has been excavated 3 times by teams of archaeologists, including from the University of North Dakota, the US Forest Service and South Dakota Game and Fish, which now claims the land around the lake.

All declared it an authentic buffalo jump and reported it was used from 5,000 to 7,500 years ago for hunting buffalo. They recorded some 115 possible prehistoric sites in the Shadehill area.

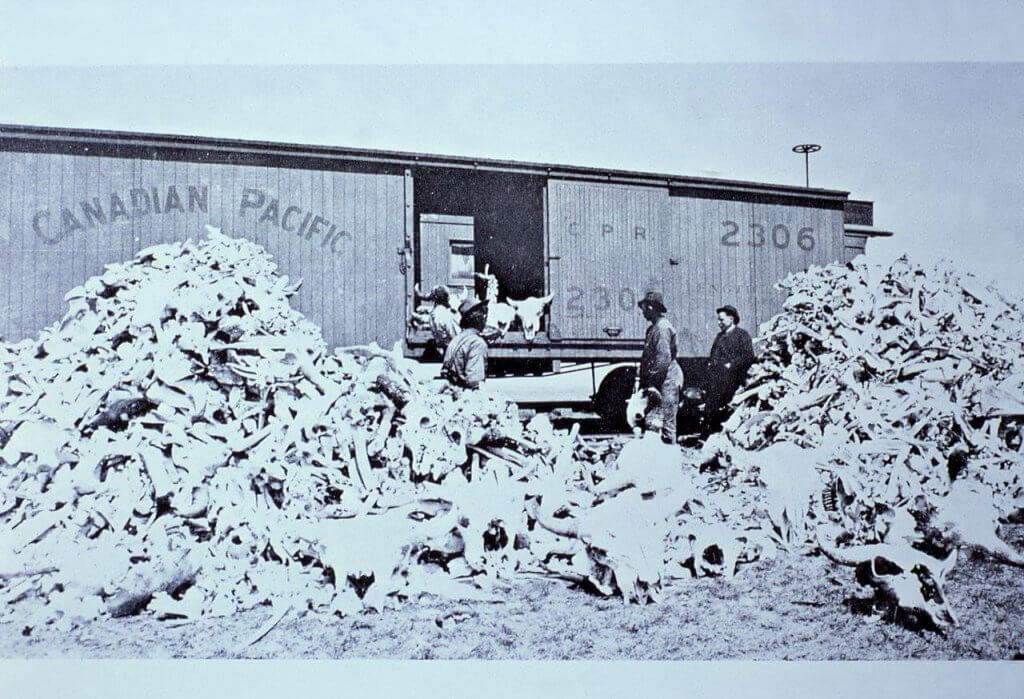

Unfortunately, our archaeologists came late to the table, after most evidence was gone. Shadehill Buffalo Jump was bulldozed during World War II, in the early 1940s, and the bones shipped by rail to west coast munitions factories to be manufactured into bombs and explosives.

It happened to buffalo jumps throughout the west—in both the US and Canada. This was called mining bones. Few buffalo jumps had been fully studied by that time, but people agreed it was important to support the war effort on the home front.

Buffalo jumps were bulldozed in both Canada and the US during WWII and the bones shipped by train to munitions factories on the west coast. There the phosphorus was extracted for explosives and bombs. Courtesy National Park Service.

“Many buffalo jump sites were vigorously mined . . . to the end of WWII,” reports a Canadian source. “Much of the natural phosphorus extracted from the bones went for the manufacture of munitions.”

The landowner of Shadehill Cliff brought in a bulldozer, scooped out the top layer of bones, then the next layer and shipped them out by train, according to Don Merriman, an old-timer in the area.

During the early 1950s the north and south Grand Rivers were dammed here where they ran together and covered any deteriorating bones with water.

We’ve searched the plateau above the cliff for clues of drift lines—but found only one small pile of rocks that appear may have been carried there by human hands.

Two Spectacular Buffalo Jumps

Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump near Fort MacLeod, Alberta, first used about 5,700 years ago, is one of the oldest known buffalo jumps in the world. It is off a large flattop butte with rocky drop-offs on nearly all sides, but with areas for the buffalo to graze their way to the top. Photo by Francie M. Berg.

In 2016 my sisters Anne and Jeanie and I drove up to investigate two of the most spectacular and famous buffalo jumps in the world—one in Canada, just north of Glacier Park—and the other some 300 miles south.

They are Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump near Fort MacLeod in southern Alberta and First Peoples Buffalo Jump, near Great Falls, Montana.

Both jumps are off large mesa-like flat-top buttes with cliffs and rocky drop-offs on nearly all sides—but with one or more easy ways for buffalo to travel up there on top to graze. Both have extensive visitor centers that exhibit artifacts from their bone piles.

Head-Smashed-In was ideally located for buffalo in hilly, broken country close to a river, with excellent grazing of the massive basin area and wide plateaus above the jump.

It was first used about 5,700 years ago, one of the oldest known buffalo jumps in the world.

The Head-Smashed-In name comes from a Blackfoot oral tradition of a young boy who wanted to watch the buffalo fall from the cliff. He found a protective overhang and hid as they came thundering over.

The hunt was unusually good that day. Unfortunately, as the buffalo bodies piled up, the small boy became trapped between them and the cliff. When his family came for the butchering, they found him—to their sorrow—with skull crushed by the heavy buffalo carcasses.

Originally the drop off the rocky cliff was around 65 feet, but bone and other deposits have piled halfway up over the thousands of years, leaving only a 33 ft. drop.

We learned that the hunting parties quick-butchered their carcasses at the jump site, then finished processing meat and hides farther below at a camping site near water. Both areas were rich in artifacts.

In the same area, several other jumps are known, as are additional camping and processing sites, a vision-quest site, a historic burial site, eagle-trapping pits, bedrock quarries and a series of petroglyphs.

Named as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1981, Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump has a magnificent interpretive center with outstanding exhibits. Research began there in the early 1960s.

It is being operated with the close involvement of Native Blackfoot people from the area whose ancestors hunted here. The Blackfoot guides help design exhibits and tell stories passed down by their elders.

First Peoples Buffalo Jump State Park, west of Great Falls MT, formerly known as the Ulm jump, is located on a rocky escarpment so long that it is called ‘possibly the world’s largest buffalo jump.’

First Peoples has a spectacular location in the Missouri River valley where the Rocky Mountains rise rapidly to the Continental Divide on the west and south, and nearby Highwood and Little Belt Mountains stand out as dramatic uplifts in the surrounding plains.

The rocky crest has an average drop of 21 feet on the nearly mile-long butte.

In places an optical illusion seems to disguise the rocky drop-off below. Looking down the final run of the drive, the rocky cliff seems to disappear and the lower prairie to merge with it. Perhaps the buffalo saw only the vast prairie in front of them—leading to escape and relief from the pressing force of the hunters—as they stampeded toward green grass below.

First People’s Buffalo Jump near Great Falls MT, is located in the Missouri River valley with a view of the Rockies and Little Belt Mountains. On the plateau above, an optical illusion seems to blend into the grasslands below, so buffalo stampeding down this last slope could easily mistake the grass ahead for a continuation of the gradual slope—and end up smashed on the rocks below. Photo FB.

Beneath the drop-off, concentrated cultural materials of bones and artifacts stretch for over 1,000 feet along the butte, and less dense remains extend nearly 10,000 feet.

The earliest of three carbon datings is 1,000 years ago, with many areas as yet undated.

Artifacts found here include tools, arrowheads and lance points, scrapers, cutting tools, broken pottery and a maul for pounding dried meat and berries into pemmican. The Interpretive building opened in 1999 and is staffed full time. People were concerned over looting, being so close to the population center of Great Falls.

During World War II, 328 tons of bones were shipped out to munitions plants on the west coast from below the First People jumps and its butchering sites.

These two famous jumps are amazing—and we learned a lot about how the buffalo could be driven from the plateau above the jump. It was not simple—and everything had to work just right.

We highly recommend both jumps to everyone interested in buffalo.

When we arrived we knew about the two lower parts of the buffalo jump—the cliff and the bone piles. But what we didn’t know—secrets of the drive lines on the plateau above the jumps—proved to be even more interesting.

Cairns—Small, Flat Rock Piles

One key to success of buffalo jumps lay with skilled use of the ‘gathering basin’ and the cairn lines on the plateau above the jump.

Hunters and stone cairns held the high ground on both sides, pressuring the buffalo to stay low. Buffalo handlers today often say that their buffalo prefer to stay high, rather than to graze in low areas.

Native hunters could use alternate ways as they set up drive lines—depending on where the buffalo were grazing and the wind direction. Other likely sites on the butte apparently exist but have yet to be excavated.

Seeing all this required us to drive way up on top—first challenge, the road could be steep, and a bit of hiking—to understand connections between the red flags that marked rock piles. But it was worth it. An amazing system indeed!

What we saw was a lot of small flat piles of rock wandering in lines several directions, up and down the hills for miles. But we couldn’t even imagine how they’d work as drive lines to force a herd of wild buffalo to jump off a cliff.

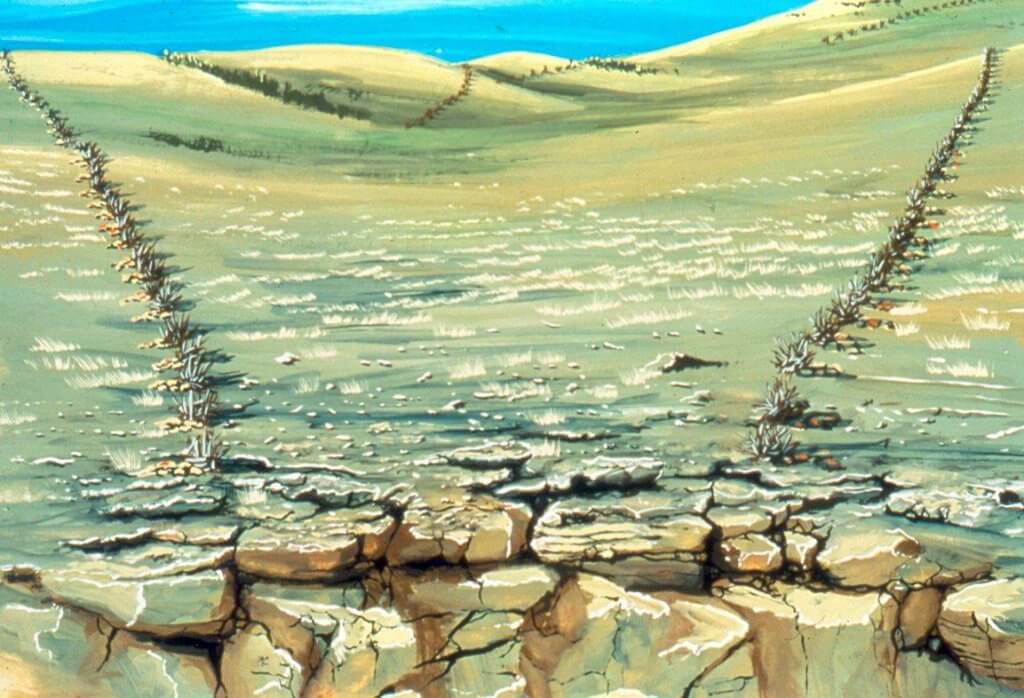

Snaking over the broad plateau at First People’s Jump, a complex of rock piles can be seen leading off to the center right and also to Anne’s left and the center of this photo. Lighter circles indicate flat rock piles or cairns. This is believed to be part of the ‘Gathering Basin’ where the herd was gradually being brought together for the final stampede. Credit FB.

We had no idea of just how knowledgeable and precise those ancient engineers were in forcing the buffalo to go exactly where they wanted them.

Prehistoric engineers—who studied every nuance of buffalo behavior—knew buffalo habits, their movements, how they swayed when they walked. Covered by a buffalo robe—they could move exactly like a buffalo and repeat their exact sounds, like the plaintive cry of a buffalo calf who had lost its mother.

They worked in harmony with the buffalo’s natural instinct and traits—such as their herding instinct, their tendency to stampede and run faster and faster when panicked and threatened by heavy horned animals pressing on every side, unfocused eyesight that took in 90% of their surroundings but failed to focus clearly straight ahead, the reassurance of a well-used trail, and their natural curiosity that caused them to follow a dancing, prancing shaman closer to the cliff’s edge.

Some rock piles on First People’s Jump are more extensive than others, especially as they cluster nearer to the drop-off itself. Many, but not all sites are marked with a red flag. The rocks had evidently been carried here, but were lying on top of the ground, with seemingly no intent to bury them deeper. FB.

On the plateau above Head-Smashed-In, a massive drive lane complex and hundreds of small rock piles extend over six miles back from the drop-off cliff. They snake over the hills, wings spread wide across the plain, and then like a funnel converge into a narrow drop-off at the edge of the cliff.

Spaced 5 to 10 yards apart, the rock piles stretch out to the west from what is called the gathering basin and form drive lanes coming in from several directions.

At one time anthropologists believed that such rock piles—called cairns—were built up high enough for women and children to hide behind, appearing and waving hides when needed.

However, Archaeologist Jack Brink, curator at the Royal Alberta Museum in Edmonton, Canada, who works with the Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump and also wrote the book Imagining Head-Smashed-In says, “The cairns at Head-Smashed-In are low platforms of stone. Our digging confirmed that they were never tall piles.

“In and of themselves, I could not imagine that cairns would help direct the course of stampeding herds of buffalo, but they could have served as the base on which to construct organic structures.”

Justly proud of not only his gathering basin, but the extensive drive lines leading to it at Head-Smashed-In—low piles of flat rocks—reaching back for miles, Brink explains how the system works.

Current thinking is that the rock piles were locations that prehistoric people built up with fresh brush or tree branches and long grasses, held in place by rocks, clumps of sod and dried manure.

This would appear as a living structure to wave in the breeze and give a sense of motion, as if hunters were waving hides all along the drive lines.

Prehistoric people likely propped up tree branches, brush and grasses with rocks, clumps of sod and buffalo chips at each rock location. There they’d wave in the breeze conveying a sense of motion, as if hunters were waving hides all along the drive lines. Courtesy of Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump Heritage Site, JBrink.

It is believed that buffalo saw these lines as solid walls along the heights. This would have tended to keep them down low as they moved away from them, feeding deeper into the funnel that led toward the cliff.

“Indians are stationed by the side of some of these stakes to keep them in motion, so that the buffaloes suppose them ALL to be human beings,” was reported.

“We can be certain that a great deal of thought, planning, and trial and error went into discovering the only suitable places that drive lanes would successfully control the movement of bison,” writes Brink.

“Mistakes were no doubt made, lanes placed in wrong locations, and herds escaped from the trap. Reassessment would have been made, cairns shifted to create slightly different land direction or perhaps more cairns added to strengthen a particularly vulnerable spot.

“With such a great amount of effort going into each drive, and considering the importance of success, it is not surprising people designed a method to mark the proper route of the drive in a way that would last for generations to come.

“Small rock piles accomplished this goal. The rock piles would serve as a permanent marker of the correct route for the drive. If the jump was not returned to for several years, the organic materials might be all gone.”

Preparation began days or even weeks before the actual hunt. The medicine leaders began ceremonies that prepared both people and buffalo.

When the time was right, women and others began building up the living fence as indicated by previous hunters over the centuries. How these were used would depend on the terrain, the location of the herd and wind direction on the day of the hunt.

Wind was important, Brink reminded us. “Buffalo are constantly checking the wind . . . wind is the carrier of the smells [and sounds] that reach the noses of the animals.”

He says that a successful hunt depended on the hunters being downwind of the herd—“that is . . . the wind blows from the buffalo.

“But if the reverse, [the hunter] will find it impossible to approach them, however securely he may have concealed himself from their sight.”

Over his years there, Jack Brink, now retired, extensively studied the rock piles for clues on how the drive lines were rebuilt each time they were used.

He gave us some clues—and even imagined ideas for which the evidence is long gone.

One was placing a line of buffalo chips that might have indicated a well-used trail between the drive lines for the buffalo to follow to the drop-off.

That certainly made sense to us. He credits Billy Strikes With a Gun, an elderly Blackfoot hunter, with giving him that idea.

Raised by his grandparents, Strikes With a Gun was familiar with ancient stories. He told Brink how buffalo runners rubbed their bodies and moccasins with sage to hide their human smell. Then they heaped buffalo chips on buffalo hides and dragged them until they reached the place where the drive would begin.

When finished, the drive lines may have looked like this, snaking over the hills for miles, with the aim of keeping buffalo down in the lower valley, funneling toward the drop-off. Jack Brink suggests we imagine a line of buffalo chips coming down a center trail between the drive lines to entice the buffalo to keep moving forward. Sketch courtesy of Head-Smashed-In, JBrink.

There they walked backwards dragging the hides to cover their footprints. At the same time they tossed out chips in a long row of dark manure patties leading all the way to the cliff.

Ancient hunters knew bison prefer to follow an existing trail. After all, a beaten track marked by dark patties of manure surely must lead to safety.

Brink said he has never read about hunters making such a trail in any report on the jumps.

But of course, such evidence would have been long gone by the time our anthropologists arrived. No expert could have dug this idea out of the bone pile.

With scattered piles of buffalo manure, “A herd of bison, frightened by hunters circling around them, could see and smell a safe path of escape,” explained Brink.

A second lure to handling a herd of buffalo, he suggests—would likely happen if a couple of boys disguised as buffalo calves went into position between the herd and the drive lanes, moving precisely as a buffalo calf would and crying plaintive lost-calf bleats.

He says a calf in danger cannot be ignored by female buffalo.

The buffalo cows would respond and walk “into the jaws of the trap.”

“What a great ruse the Plains people pulled off!” Brink exclaims. “Drive lines worked extraordinarily well to keep the bison contained in a specified area because, by their movement, the stacks of brush gave the appearance of something to be feared—a strange object moving in the distance.”

Moving buffalo from the gathering basin to the drop-off was not necessarily the work of a single day.

Sometimes a line of smoke and flames held the secret to the jump’s success.

When using fire, hunters gradually formed a semicircle behind the herd. At a signal from the hunt leader, each fired the dry prairie grass in front of him, creating a wave of crackling flames. Panicked, the buffalo ran faster and faster in their final stampede.

“Before the buffalo run, a ceremony took place, with prayers to the Great Spirit that all would go well, for success in the hunt with no injury or accidents,” wrote Josephine Waggoner, an early Hunkpapa historian.

When all was ready and the medicine was right, the hunters gradually directed their prey between the lanes. Religious rites, prayers and thanksgiving played an important part in every hunt, as in daily life.

Frison’s Research on Stampedes

An early researcher of buffalo jumps was George Frison—head of the Anthropology Department at the University of Wyoming. He spent his early years in cattle ranching in Wyoming, while at the same time volunteering with archaeology teams digging dinosaur bones in the area.

He came to believe that archaeologists of the day did not consider the behavior of wild animals and often portrayed buffalo hunters using unrealistic and illogical methods. He became a scientist because of his dissatisfaction with theories that didn’t make sense to him as a rancher and hunter.

At the age of 37 Frison enrolled at the University of Wyoming and received his PhD five years later. Soon he was organizing field work with his students at numerous Wyoming sites and began publishing articles and books on their findings and how they fit his theories.

“Prehistoric hunters were capable of killing the animals under their own terms and not those of the animals,” write George C. Frison, Marcel Kornfeld and Mary Lou Larson in their authoritative 2010 book, Prehistoric Hunters-Gatherers of the High Plains and Rockies, now in its third edition.

George Frison, who wrote the first two editions of that book in 1978 and 1991, revolutionized theories on early hunting cultures. Today we have much data on the early hunting technique of the buffalo jump due largely to his work.

Jack W. Brink—long expert at Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump—calls Frison the “Dean of the great people in the research and study of buffalo jumps.”

“Nowhere else on earth, at any point in time, did people obtain more food in a single moment than they did at a communal bison kill,” Brink writes.

He says Frison investigated “More buffalo jumps than any other person on earth.”

When he toured the plateau above Brink’s own favorite buffalo jump he is quoted as saying only, “Now that’s a Gathering Basin!”

Frison and his students excavated many buffalo jumps over the years, testing out their theories.

As the animals moved into the gathering basin, other hunters fell in behind—at some distance—to keep the lead buffalo from turning back.

Unlike this careful planning, Jack Brink, the expert at Head-Smashed-In, says many visitors come there believing that ancient hunters simply climbed to the top of the cliff and waved hides at a herd of buffalo—while they jumped off the cliff.

As hunters ourselves we knew that never could that have worked! No way.

One day I was walking up there across the plateau—looking for rock piles—when 2 deer came trotting across between me and the drop-off.

And I thought: Even if I could run fast—faster than those deer: Could I turn them back and chase them down over the cutbank?

Absolutely not! It would be impossible.

As wild animals, buffalo are very smart, alert, acutely aware of their surroundings–and not easily tricked, even today. We know they are fast and agile—can run 40 miles an hour and spin on a dime.

They were not likely to just accidentally fall off a cliff, especially in their own territory. And if one escaped and turned back, likely all would follow.

The Stampede Had to be Just Right

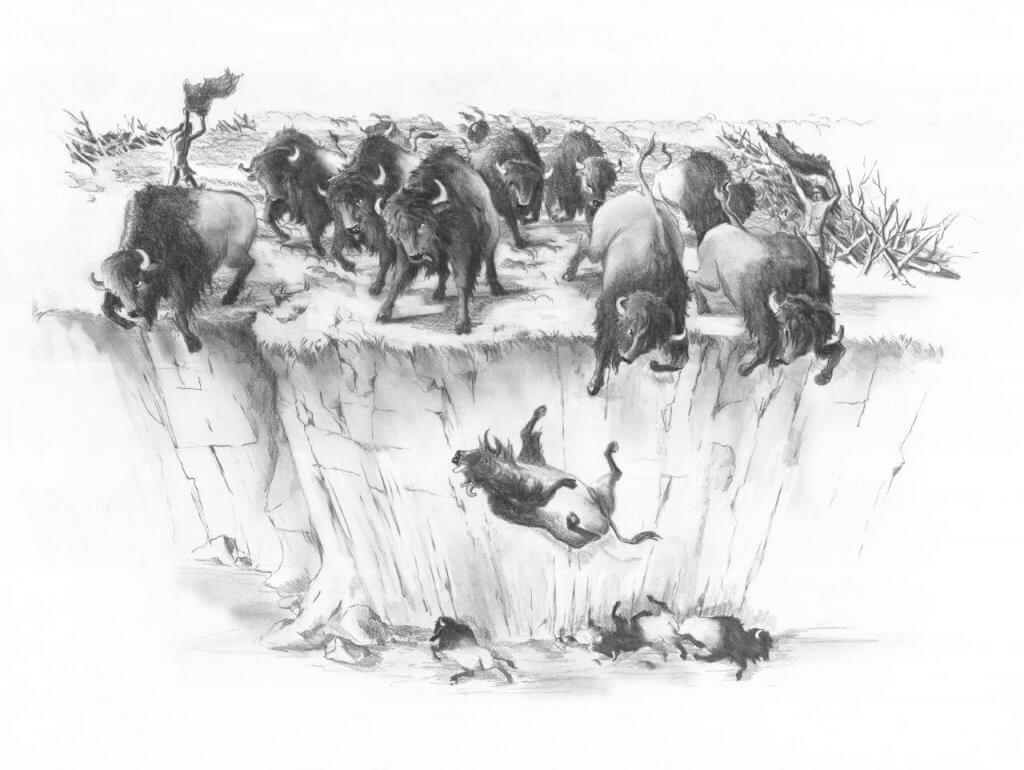

The Wyoming team reported that using a stampede successfully would have required a rather large number of buffalo.

If hunters on foot tried to bring a small herd to the cliff, the leaders would detect trouble in time to stop, turn aside or do a sudden 180 turn and escape.

This sketch shows the buffalo above the cliff probably would had have a good chance to escape—there’s space to lunge either to the right or the left. It looks as though this stampede has failed and the men waving robes are in a very dangerous position.

They speculated that even three or four experienced cowboys on well-trained horses could never force a single buffalo or even a group of 10 or so off a jump-off. But with 50 or more buffalo, they would have had better luck.

No one knew their prey better than did these ancient hunters of the prairies and plains.

One secret of every jump was how to get the stampede right.

The Frison team said all the buffalo need to be running hard and closing up on each other—to the very last moment.

Starting the stampede fairly close to the cliff, perhaps less than a half-mile away, the hunters would press hard, plunging them into an all-out stampede. With huge bodies packed tight on all sides, stout horns slashing from behind, all charging at full speed—the animals in the lead could not stop or slow down.

The mass of horned animals behind would have prevented it and carried them over the precipice.

Also, if there ‘just happened’ to be a surprisingly sudden turn at the end—planned of course—all the better. The leaders could not focus on that abrupt danger until too late. And over they went.

This painting shows the high risk for hunters stationed at the end of the drive, as stampeding buffalo finally realize their desperate choice—to take on the men waving hides or the cliff. Credit Shane Tolman, artist, from the book “Imagining Head-Smashed-in,” by Jack Brink.

The cliff scene is summed up by George Frison, expert of countless buffalo jumps:

“The final moments of a great buffalo drive were without parallel in the events of world prehistory. Nowhere else, on any continent at any time, did human beings kill such a staggering amount of food in a single moment.

“For sheer raw power, unbridled danger, nail-biting suspense and rampant drama, there may be nothing in the archaeological record that can match the final few seconds of a herd of stampeding buffalo arriving at the edge of a steep cliff.”

After the buffalo plunged over, hunters rushed to finish off injured animals that survived the fall, killing them with clubs, bows and arrows and lances shaped with stone tools and tipped with stone, bone or shells.

They completed the butchering process at a nearby camp using stone scrapers and knives, fleshers of shoulder blade bones, and punches from elk antlers and they pounded dried meat into pemmican with grooved mauls made from smooth river stones.

Over a thousand years later many such artifacts have been dug out of bone beds beneath the jumps.

Other known Jumps

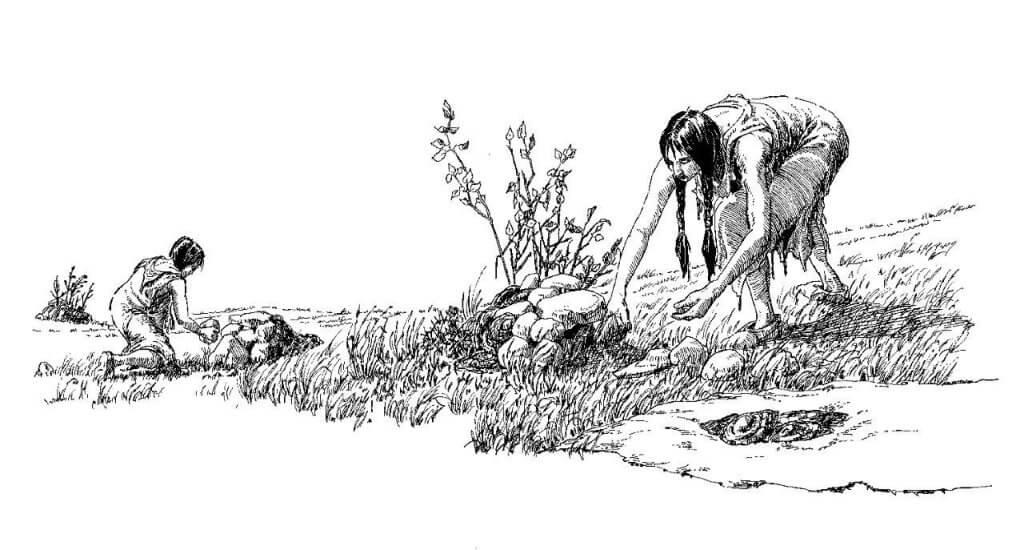

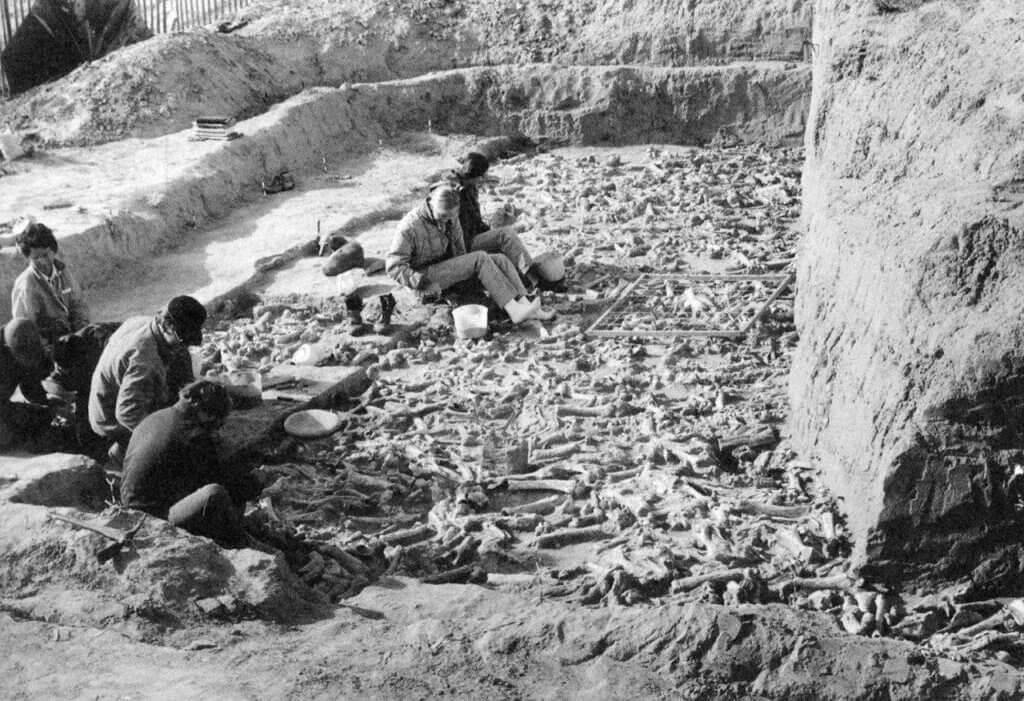

Searching for artifacts—is meticulous work for archaeologists and their helpers as a bone pile site is laid open. Likely it will be covered over again when the dig period is finished. Credit ‘Pisskan,’ Leslie Davis and John Fisher, Edit.

Known buffalo jumps number in the hundreds across the Plains, and experts say they likely represent only a small percent of what is out there.

Other well-known Canadian sites include the Old Women’s Buffalo Jump, and Dry Island Buffalo Jump Provincial Park.

Montana reportedly has the highest concentrations of Buffalo Jumps, but only three with interpretive centers. In addition to First Peoples, these are Madison Buffalo Jump State Park, west of Logan and the Little River site west of Havre.

Other jumps are known in southeastern Montana, Big Horn County, where HooDoo Creek runs into Dry Head Creek, used by the Crow Indians.

The complex of drive lanes and jump cliffs is known to the Crow Tribe as Where They Get Their Meat, says Joseph Medicine Crow of the Crow Indians.

Other jumps include the Yonkee complex near Broadus MT, and nearby, the Vore site in that corner of Wyoming.

Jumps had many variations, depending on the terrain, herd location and wind direction.

The Vore Buffalo Jump, not far from Devil’s Tower in northeast Wyoming, does not involve a cliff at all, but rather, a trap. Vore, named for the rancher who found it and donated the land, is a large natural sinkhole at the base of a long sloping ravine that opens out into a broad, flat valley, conveniently just off Highway I-90.

In fact, it was discovered in scoping out that Interstate, which now takes a sudden turn to avoid the sinkhole, which opened up around 1550 and was used by many tribes through 1800.

Many jumps that have been investigated in the past are really begging for reworking and reinterpretation, given the knowledge and methods now available, wrote Frison.

Many other likely sites, doubtless well used in their day, are located but have not been excavated or verified.

*Note: This buffalo jump off the cliffs at Shadehill Lake is labeled Site 6 (south side) and 6b (north side) on our historic Buffalo Trails Tour. The Shadehill Buffalo Jump is best viewed from the north side of the lake. Visitors can also drive close to the actual Buffalo Jump on the south side. There they will find, in addition to what is left of the buffalo jump, the Hugh Glass monument honoring the heroic struggle of the fur trapper mauled by a grizzly bear here in 1823. In 2016 Leonardo DiCaprio won an Oscar by re-imagining that epic struggle in the movie The Revenant, also an Oscar winner. However, the true facts are stark enough. Pursued by vengeful Arikara, injured, defenseless and without weapons, Glass crawled, mostly by night, the 200 miles to safety at Fort Kiowa, SD. But the tough mountain man did not rest long in his quest for valuable furs. He joined up with another party of trappers and immediately headed west.

References:

Brink, Jack W. “Imagining Head-Smashed-In: Aboriginal Buffalo Hunting on the Northern Plains,” 2008. Athabasca University Press, Edmonton, Canada.

Davis, Leslie B. and John W. Fisher Jr., Editors. Pisskan: Interpreting First Peoples Bison Kills at Heritage Parks, 2016. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Gilfillan, Archer. SD Highway Magazine, 1939. South Dakota Game, Fish and Parks.

Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump, Personal visit, June 15-23, 2016.

Hornaday, William T. “The Extermination of the American Bison,” Report of the National Museum, 1887. Reprinted in book form by Gov. Printing Office, 1889.

Kornfeld, Marcel, George C. Frison and Mary Lou Larson. “Prehistoric Hunters-Gatherers of the High Plains and Rockies,” 3rd Edition, 2010. Left Coast Press, Walnut Creek, CA.

Lame Deer, John (Fire) and Richard Erdoes. “Lame Deer Seeker of Visions.” NY: Simon and Schuster, 1972.

Merriman, Don. ShadeHill, Personal Communication, 2015.

Ulm Pishkun State Park, Personal visit, June 15-23, 2016.

Vore Buffalo Jump, Personal Visit and Interviews 2016, Vore Buffalo Jump

Waggoner, Josephine. “Witness: A Hunkpapha Historian’s Strong-Heart Song of the Lakotas.” Edit Emily Levine. U of Nebr Press, Lincoln, 2013.

____

NEXT: HUNTS BEFORE HORSES AND GUNS, PART 2

_______

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog