Feeding an orphan calf is an emergency situation. It has to be done “right now!” And it is a time commitment.

So it’s a good idea to be prepared.

Calving season has arrived and so have many new buffalo babies. It’s an exciting time of the year when new calves are welcomed to the world.

Fortunately for you who are buffalo ranchers there are usually few problems associated with calving.

Happy scenario for both calf and mother.

However, it may happen that a calf is abandoned—perhaps the weakest of a set of twins—or the mother cow dies, or for some other reason a calf must be removed from the pasture and raised by hand.

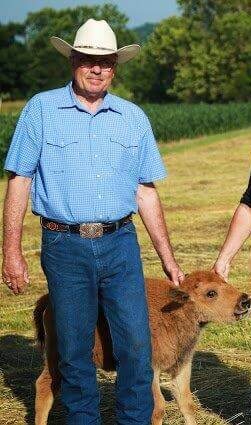

Buster—an orphan well cared for by his family. Buster grew up on the ranch and was able to stay in the breeding herd for awhile, although “he was a bit of a loner,” said Randy. Credit Randy Miller.

Miller has been a leader in the Bison Association of Nebraska for many years. He has been in the bison business since 1995.

Randy’s daughter Megan Olesiak works in the Miller buffalo ranch company at NebraskaBison.com. They have a second herd, Miller Bison at Elkhead Ranch, just over the line in Missouri.

Buster lies down. “Experienced producers like to keep the calves a little hungry at each feeding.” Fewer digestive upsets. They can be weaned from milk at 3 to 4 months. Photo RM.

Megan told me, “You need to be careful when you make a pet of a bison bull calf. They grow up.

“One time when I was a child—we were just getting started with bison. I was sitting in the pickup with the window open. We had a pet bull and he put his head in for a treat.

“And then he lifted his head and took the door off!”

Four Generations of Bison

My almost neighbors Steve and Roxann McFarland have had about 3 or 4 orphan calves in the 20 years they’ve been raising buffalo southwest of Hettinger.

“Some others may have been born as twins and the coyotes got one of them before we did,” Steve says.

“Each bottle calf we’ve raised has had its own personality. Some learn quickly to follow a bottle, some have been pretty stubborn.”

Actually Steve grew up with buffalo as his father, grandfather and great-grandfather raised buffalo on their South Dakota ranch before he was even born.

As a 4th generation bison rancher Steve grew up helping with bison and bottle calves. It was his great-grandfather who first bought 3 or 4 bison heifers and a bull, just to try them out with his cattle herd. His grandfather Roy improved the herd and so did his father Eugene.

Their daughter Ashley showed her bison calf as a 4-H project at our Adams County Fair a few years ago—under a new class called “Exotics.” Her’s was the only exhibit in the event that year.

Good for Ashley! She’s a pioneer!

Even as a long-term 4-H leader I have never heard of this before except in Canada—where I think Alberta has a 4-H project called “Raising Bison.” Don’t know if they have a booklet for 4-Hers to study.

I’ve seen a photo of one and have written for information, but so far have been unable to find any.

Steve says her calf was apparently a twin born around the first of May and found abandoned. Raised as a bottle calf, they helped Ashley halter break him and she showed him in August at our 4-H fair.

Roxann, Steve’s wife, says a bottle calf seems to get attached to one particular person—perhaps it imprints on whoever feeds it. Often that person is her.

“One calf got so lonesome whenever no one was with him,” she says. “In fact when he was alone he wore all the hair off his head, rubbing it along a plank in his pen.

“We tried a goat for companionship—he was full grown and we thought he could hold his own. But the little bull chased him right out of the pen.

“We put him back in—and soon he was outside again. Then we got another baby buffalo. First time we had 2 together,” Roxann recalls.

“They bonded and hung together—Oscar and Gus, both bull calves–always stayed together even after they grew much bigger. We sold them to a bison feeder.

“They were too dangerous to keep.

“The new owner said as long as he had them, the two bulls always insisted on being close together.”

Feeding Tips

Here are feeding tips from Gerald Hauer, Bison Production Specialist, Bison Centre of Excellence, in Leduc, Alberta, from his article “Feeding Orphans,” as reprinted from “The Tracker,” volume 4, Issue 5, June 2000, in Bison Producers of Alberta.

He begins with the importance of colostrum—the mother’s first milk:

“Calves are born with no resistance to bacteria and viruses and must absorb antibodies from their mother’s first milk or colostrum to be able to fight off disease. There are high levels of antibodies in colostrum and the calf’s intestines have the ability to absorb these antibodies from the inside of the gut into the bloodstream for the first few hours of life.

“The intestine loses this ability within 4-12 hours after birth so it is very important that the calf receives its colostrum within this time period. Always give colostrum for the first few feedings.

“Cattle colostrum or commercial dried colostrum replacers can be used as a substitute for real bison colostrum which is hard to obtain.

It takes time to bottle feed bum calves, but economists say it’s well worth the care it demands.

“Often surrogate mothers are not readily available so artificial rearing is the only option. What to feed is a common question. Bison calves have been raised successfully on cow’s milk, cow milk replacer, sheep and goat milk replacer and goat’s milk.

“There is now a commercially available bison milk replacer made by Brown’s Feeds. Sheep milk replacer is frequently used because it closely resembles the composition of bison milk.

Note: Two recommended feeds for bison babies are Bison Milk Replacer from Browns Feed https://www.hibrow.ca/browns-feed and BisonGro from Zukudla http://www.zukudla.com/milk-replacers-bisongro

“Once the calf has a good start with colostrum, it is time to feed milk or milk replacer. Some people have had good success by finding a nurse mother for their orphans. A recent article in the ‘Smoke Signals’ outlined one producer’s success with using a highland cattle cow as a surrogate mother for his bison orphans.

“If you are considering using goats to raise your calves I would recommend having them tested for malignant catarrhal fever and Johne’s disease.

“One experienced producer uses real sheep milk available from one of the few sheep dairies in the province. She reports that there are fewer digestive problems with the real sheep’s milk and is worth the extra cost.

“It would be a good idea to pasteurize the sheep milk to decrease the chance of introducing MCF virus into your calves.

Feeding Frequency

“How often should they be fed? Frequent feedings of small amounts will decrease the chances of digestive upsets. Bison calves are usually fed 4 times daily for the first few weeks and this is gradually decreased to 2 times daily by two months of age,” writes Gerald Hauer

“How much to feed depends on the size of the calf. As a rule the calf should be a little hungry at the end of each feeding. If they are allowed to drink their fill they will be prone to digestive upsets and diarrhea.

Orphan calf enjoys a back rub when finished with his bottle. RM.

“Experienced producers like to keep the calves a little hungry at each feeding. Most calves require about 10-20% of their body weight in milk each day. This works out to about 500-800 mL per feeding for bison calves.

“As the calves get older and the feedings become less frequent the volumes fed at each feeding can be increased.

“Once the calves are few weeks old it is a good idea to introduce them to some grain and hay or grass so they can nibble on some solid feed. By the time they are a few months old they should be eating a significant amount of feed.

“Calves can be weaned from milk at 3-4 months of age and put onto a good quality diet.

“Other tips to help keep your calves healthy are as follows:

- Wash the bottles and nipples after each feeding to decrease the bacterial buildup. Good hygiene can prevent problems associated with contamination of your equipment.

- Allow access to soil so calves can lick it as this may provide some nutrients.

- Salt and minerals should also be available.

- Build a pen that allows lots of room for exercise.

- Try not to keep one calf by itself. Provide another calf to keep it company.

“Raising an orphan bison is a lot of work. Before undertaking the job you should become familiar with the husbandry that is required. “

For more information Hauer recommends the following “Bison Breeder’s Handbook, National Bison Association; Bringing Up Baby,” by Peter Haase, Smoke Signals, April 2000. www.bisoncentre.com › feeding-orphans

Imprinting and Sucking

“The Journal of Buffalo Science,” published in Canada says it is important that mother and calf are able to bond immediately at birth. In the article “Imprinting, Sucking and Allosucking Behaviors in Buffalo Calves,” 2018, 7 (Lifescience Global), Patricia Mora-Medina, from the University of Mexico (UNAM), Fabio Napolitaano, U of Basilicata, Italy et al write:

“From the perspective of the [buffalo] offspring, recognizing their parents is essential for their welfare and survival, since the dams feed only their own young.

“This learning process, defined as imprinting, occurs in a sensitive period under the control of oestrogens and oxytocin, which are abundantly produced at parturition (birth).

“After a few hours the level of these hormones lowers and dams become unable to develop appropriate maternal behavior toward the newborn calves.”

“The amniotic fluid that covers the newborn is attractive to the mother and while licking they learn its specific odor thus promoting the mother–young bond. Lack of amniotic fluid may cause rejection of the newborn.

“The most important aspect of the birth process is that calves must quickly locate the udder and begin to suck their mothers’ milk. Suckling and the maternal care for calves allow them to survive and grow.

“As the calf passes through the birth canal during parturition it generates cervical-vaginal stimulation that activates the hypothalamus and releases oxytocin, a hormone that acts upon the cow’s olfactory bulb. This, in turn, enables the secretion of dopamine, which initiates the sensitive period during which the dam identifies her own calf.”

After giving birth, says this source, the mother stands up and begins to lick and smell her newborn calf. In buffalo (and dairy and beef cattle) this stimulates various activities in the calf, including the respiratory center, breathing, circulation, urination and defecation.

The newborn buffalo calf raises its head and adopts a ventral-sternal posture, followed by hesitant attempts to stand on all fours, first extending the thoracic extremities, then the pelvic ones. These movements allow the calf to reach the mammary gland and begin feeding. Other behaviors include vocalizing to attract the mother’s attention as part of the calf’s survival strategy.

Given all this, say these researchers, it is essential that the buffalo mother-calf bond develops from the moment of birth and through the immediate postpartum period.

Practices like early separation and artificial rearing generate stress in both buffalo cows and calves

“In the context of these behavioral changes, the sex of the neonate seems to play a role, as female calves show faster development than male calves.”

Mixed Blessing: Triplet Buffalo Calves

Triplets arrived at the Buffalo Horn Ranch in Alberta, the first ever reported—a mixed blessing. Photo used by permission, Peter Haase, Buffalo Horn Ranch © 1999.

“This spring we were triply blessed with a set of triplet bison calves, reported Peter Haase, of the Buffalo Horn Ranch, Alberta, Canada, in April 1999.

“Actually, it was something of a mixed blessing getting three heifer calves and then being confined to the ranch with the numerous feedings. We have some experience working with abandoned calves over the years with mixed results. One of our foundation cows is bottle raised.”

“With the publicity, our babies also became poster girls for ‘Brown’s Bison Milk Replacer,’ a new product becoming commercially available. We were fortunate in that many experienced bison producers gave us advice on how to raise these girls properly.

“A bison cow normally only has enough milk for one calf, so both are compromised when it comes to competing for the limited milk that mom is able to offer. Often one calf won’t get quite enough and will begin to fall behind, while its sibling grows stronger.

“It may take only a few hours or it might take a few weeks, but the usual scenario is that one calf is left behind as a meal for the predators. In the confined pastures of a ranch, the likelihood of a cow raising twins is perhaps somewhat higher than in the wild.

Recently Peter told me that the mother was named Nakimu—and hers were the first ever reported bison triplets—all female. They were named Moon Beam, Moon Shine and Moon Shadow.

“We watched these closely. The first day the mother walked away from Moon Beam—we took her. The next day she walked away from Moon Shine. She raised Moon Shadow. The other two were bottle fed.

“The last of the bottle raised calves died in 2021 of natural causes. This is after the mother having and raising 18 calves, never missing a year until her last year. The other bottle raised sister died in 2016 and her sister, raised by the cow, died at age 10. In fact Nakimu had 2 sets of twins besides the triplets.

“The birth of the first recorded bison triplets gave us a great deal of publicity in numerous newspapers, magazines and on two national television networks.

“From our research, we have found that most abandoned calves are twins. Are twins more common today? I don’t know, I suspect that we are discovering more twins for a couple of reasons aside from there being more bison.

“Firstly, we producers are checking our herds more closely than before, so perhaps we discover the twins before the coyotes do. Secondly, we are more careful with the bison’s nutrition and health care and this too might contribute to more twins.

“We had a situation with our second calf ever being born. This calf was born at night and in the confusion of 60 heifers, the heifer calf bonded with a young cow who already had a two-week old calf.

“The new mother was frantic looking for her calf and the other cow was running around with two calves. After about 30 hours she didn’t want anything to do with this calf and abandoned it.

“We grabbed her calf at that point, gave colostrum and bottle raised her for three weeks before she died of Navel Ill. The colostrum we gave was too late and did nothing for her immune system.

“The mother of this abandoned calf found another heifer calving about the time that we grabbed her calf. She bonded with the new calf and this calf sucked on his ‘twin’ mothers all summer.

“The lesson here is that the calf must have colostrum in the first 6 to 12 hours or its chances of survival are slim.

“Another note here, we have a five-year-old bottle-raised cow that we purchased as a calf. One thing she really lacks is mothering ability.

“She never licks off her calf, nor does she look out for it very well. Fortunately, she has had two very persistent calves who have done very well despite the shortcomings of their mother. There is more to being a mother bison than instinct, there must be something learned as well.”

Good mothering. Buffalo mothers are naturally protective of one calf. Sometimes a twin gets neglected. SD Game & Fish, Chris Hull Photo.

Carrington Bison Research attempts Alarming Rescue

Bison Research conducted at the Carrington Research Extension Center, North Dakota State University for a few years, published a report in 2001 on “Managing Very Young Bison Calves,” by Vern Anderson, Dale Burr, Tim Schroeder, Chris Kubal and Eric Bock.

The researchers worked frantically for many weeks trying to keep 69 bison calves of all ages alive. They concluded:

“It appears the success rate is very low when caring for orphan bison calves under the age of 4 weeks unless significant individual attention can be given to each calf.

“These animals are simply too dependent on mother’s milk and cannot be acclimated to milk replacer and starter feeds as a group.

For their research the Carrington Center accepted a donation of 69 bison calves ranging in age from two days to two months, delivered on June 4, 2001. Their mothers had been managed as feeder heifers and were scheduled for market. Some had been bred accidentally.

“At the time in 2001 there was virtually no nutritional information or guidelines on the care of baby bison prior to weaning,” says Dr Vern Anderson.

“Consultation with a number of experienced bison producers suggested we had a major challenge on our hands.”

Turned out they did indeed! It was a desperate situation for the researchers. All of them working every available minute to save all those calves.

It probably couldn’t be done with the manpower available. But they met the challenge as best they could.

First they separated the 16 youngest and smallest and kept them in a small fenced area, while the older calves moved to a one-acre grass pasture.

“Catching these youngest animals, even in a small pen, proved to be a challenge. At the young age of the calves, they were fast and strong and fought being handled. Roping calves caused severe stress from chasing with some choking and shock resulting when calves were caught.

They refused to suck from a bottle. None of the calves adapted to that even after several days. None of these younger calves survived to the end of their first month. The experience turned out to be very stressful for handlers and calves.

“Handling (catching, ear-tagging, drenching, bottle-feeding) any age of orphan calf is very stressful,” says their report.

“Most of the 16 simply starved to death. They were unwilling to nurse or fought the tube at every opportunity and did not learn to eat the dry feeds.”

Food was a problem for the older calves, too. The researchers kept changing the rations. The calves seemed to prefer barley malt pellets—which were low in protein and calories.

Barley pellets were then mixed with com, peas and wheat middlings to increase the nutrient density. Then the barley was withdrawn.

“Some commercially available, very palatable, high-protein, high-energy feeds were offered in three pans inside the pen. Two pans were used for milk replacer and fresh water was available in two others. A high quality grass hay bale was also available.

Finally on June 27, a specially formulated baby bison feed was introduced, developed by Heartland Feeds (Hubbard) at Bismarck, ND for use in this study. This new formula was more nutrient dense than the commercial starter feeds with higher protein (24%), more energy (est. 95% TDN) and less fiber.

It was a fortunate combination of field peas, corn, canola meal, com distillers dried solubles, soybean hulls, dried milk powder, molasses, yeast, fenugreek and highly bio-available vitamins and minerals.

Once they were used to this food it replaced all the commercial starter diets. At last the older calves seemed to bloom and their general health improved. The researchers wrote their opinion that having this nutrition from the start might have reduced stress and increased survival rate.

“Calves this old probably start ruminating and have the ability to survive on more traditional feeds,” they said.

Only 25 of the 69 ultimately survived. But by September 10, they appeared in good health and were transitioned to a conventional grain mix, less nutrient dense and lower in cost, 16% crude protein and approximately 80% TDN. This included corn, peas, soy hulls and wheat midds plus vitamins and minerals, offered with free-choice alfalfa hay.

Unfortunately the bottom was already falling out of the bison market by then, and after producing some remarkable pioneer research at the Carrington Station the bison studies came to a halt and were never restored.

Buffalo Handler Learns the Language

Waist deep in wild yellow sweet clover Jim Strand calls over Lucky—a grown-up pet—in the big pasture for a munch of cattle cake. Lucky can’t resist Jim’s relaxed approach and buffalo grunts, but no longer wants to be petted. Photo credit Donna Keller.

Another almost neighbor of mine is Jim Strand who manages the sizeable Blair Johnson herd of about 400 cows, southeast of Hettinger a few miles into South Dakota, where he’s had 8 or so orphans over the past 25 years.

Jim feeds lamb milk replacer because it is richer than cows’ milk. He also feeds at least 3 times a day. The last calf he had took to the bottle right away when born.

The mother of another died when the calf was about 3 weeks old and wouldn’t take the bottle, so Jim put him in with some feeders and he did just fine. I think he spends plenty of relaxed time with them.

Usually bum calves get attached to one person. Jim says he grunts like a buffalo to them and they seem to respond.

One time a friend needed to catch a rather wild buffalo calf and Jim went to help. “I’d grunt to him and he’d come a little closer. I kept coaxing and he came right up to me. I grabbed his foot and held him.

If I get one in a pen, I can usually coax, grunt and corner them.”

One pet they had was Lucky. He enjoyed being petted and talked to—the first year he stayed in the yard close to the family.

“He’s still in the herd. Now that he’s grown he still comes up when I’m around, but he doesn’t want you to pet him.”

Another pet was given him from a family in Bemidji, Minnesota. Raised there on a bottle. She got too big for them before she reached a year old, so they gave Jim a call.

Her name was LaBelle. She comes right up to him in the pasture and will take cake from his hand.

“She had a calf as a 2-year old—that’s unusual,” says Jim. “And she’s had a calf every year since—6 calves in a row.”

Favored cow LaBelle enjoys a back rub. She has raised 6 calves in a row—at only age 8. Credit DK.

Twins-More Work, Well Worth the Effort

When twins are born, it is worth the extra management effort to save both calves, Dr Roy Lewis, a veterinarian, told producers in the March 12, 2018 issue of Grainews.ca in Canada, writing on “Problems and Benefits of Twin Calves.”

“In my practice, I often hear producers complaining about twins,” he wrote. “Mainly because often the focus is on the problems they can present.

“About 8% of most common beef breeds will produce twins and it is also quite common among bison.

“Economics show there is value in making the extra effort to save the extra calf.

“Research on a twinner population over the last 10 years in the U.S. found there to be a definite economic benefit with twins. So it is important to look at both the positive and negative aspects hat come with these double deliveries.

“Some mothers accept and care for twins, as did this cow of a client,” said Dr Lewis. “But be alert for one calf failing to thrive and jump in when problems develop.” Photo credit Roy Lewis, DVM.

“There is no doubt twins can be a positive if they both arrive alive, are the same sex and you have an extra cow to foster one of the calves.

“But we all know the opposite—twins coming malpresented, then you finally get them out (with or without veterinary assistance). Both are dead and the cow doesn’t clean and becomes a problem to rebreed.

“Dystocias (birth difficulties) from fetal malpresentation are the biggest reason twins have a lower survival at birth.

“When one ponders the combinations of all the legs and two heads coming backwards and forwards, it is no wonder mixups occur.

“If we can minimize the bad scenario and come up with more positives, twins would be welcome. Keep in mind they will always require more care, attention and management skills.

“It’s important to watch the cows and calves closely and jump in when problems develop,” he writes.

An Alberta-based veterinarian specializing in large-animal practice, Dr. Lewis has served as a part-time technical services veterinarian for Merck Animal Health. He is involved in planning the International Bison Convention to be held in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, July 12-15, 2022.

Dr Lewis served on the committee updating the National Canadian “Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Bison.” That publication which was released in 2001 and updated in 2017 tries to discourage making pets of bison.

“Bison should not be raised as pets,” the Canadian Code states bluntly. “Producers opting to rear orphans should refrain from playing with calves. Bunting behavior should be discouraged at all costs.

“Adult bison that have played with humans as calves may become dangerous. Orphaned bison must not be used for breeding under any circumstances. Castration and dehorning is strongly recommended for orphans. Orphans may be able to be reintroduced into a feeding program.”

##

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog

Howdy Francie,

My name is Ed Mountain and I serve as President of the Texas Bison Association (TBA) and subscribe to your Buffalo Tales & Trails blog. I enjoyed your recent article titled ‘Saving Orphan Buffalo Calves.’ Would you consider the TBA reprinting your article in our upcoming TBA Bison Journal annual magazine?

I am not sure we can fit the whole article into the publication as we are currently creating the Journal and may be limited on the number of pages we can publish. We will be printing 500 copies of the TBA Journal, sending 150 out to our members and using the rest for events, new members and sponsorships.

In case you are not very familiar with the Texas Bison Association, here is more information about our organization.

https://texasbison.org/

Please let me know if you have any questions or if you would like to talk about this further.

Thank you,

Ed Mountain

President, Texas Bison Association

Hi Ed

Nice to hear from you. And yes, you certainly may reprint the ‘Orphan Buffalo Calves blog.’ My blogs are educational and written especially for those who teach history and also everyone who just loves buffalo—which as I understand it includes nearly everyone who raises them.

So if you’ll just add my ‘BuffaloTalesandTrails.com’ address so others can find it—that’s all I ask. And if you run out of space, just edit as needed and they’ll be able to find what’s missing.

Best Wishes, Francie M Berg

Francie, thank you for publishing this well-written and informative article about Orphan Buffalo Calves. I greatly enjoy reading your blog articles and find them informative and enjoyable. Thank you for your passion of this majestic animal and keep up the great work.

Yes, I currently have 15 bison on my small ranch. I would say the average TBA member who raises bison has about 25-50 bison on their ranch.

Thank you,

Ed Mountain

President, Texas Bison Association