Minimize Stress to Maximize Animal Health and Productivity

Story and photos by Karen Conley

Reprinted with permission from Bison World, Fall 2023, p26-32.

Connor Buchholz of Skull Creek Bison moves a group of animals up the alleyway. Note that he is on the edge of the flight zone and the animals are responding by moving away from him as he planned.

Working with bison can be stressful for both the animal and the handler. A difficult situation may be unavoidable, but it can be mitigated or avoided with the right mindset and proper handling techniques. Taking the time to understand the animals and how they perceive the world around them can pay dividends in herd health and ease of handling as well as economically for the producer.

Animals that are under stress can suffer from a compromised immune system, opening the door for disease susceptibility. Stress can also cause behavioral changes such as stampeding, herd aggression, or even “suicidal” actions, in which the animal becomes so panicked that they are a danger to themselves and everything around them. Fear, panic, or stress can trigger the release of the stress hormone cortisol into the bloodstream, which can ultimately influence the quality of the meat if that animal’s destiny is for meat production.

Bison are wild animals and they are always naturally on guard. They are highly responsive to stimuli and will react to that stimulus accordingly. One animal may vocalize more than another. One animal may react so powerfully that it shuts down and enters a state of shock, sometimes called tonic mobility.

As caretakers of the bison, the goal is to keep the stress to a minimum and work with the animal’s natural fight or flight response to get the desired outcomes.

777 Bison Ranch Herd Manager Cody Smith is one of the best at working with bison. His quiet and calm demeanor and ability to read the animals have paved the way for successfully managing the large herd at the ranch near Fairburn, SD.

Working on the ranch since high school, Smith learned from the ground up and continues to educate himself and those around him about the benefits of low-stress handling.

“When handling bison, stress is a huge deal,” says Smith. “It can lead to sickness or injury or even worse. Those signs of sickness won’t show until the stress is at a high level. Look for things like droopy ears, their tongue hanging out, a runny nose, or something as simple as a head hanging down. I also see a lack of focus when the bison are stressed out.”

Cody Smith moves a group of animals through the working facility at the 777 Bison Ranch. Photo courtesy of 777 Bison Ranch.

Smith says it’s a matter of mutual respect, not dominance when working with bison. “Bison hold grudges, so you need to be nice,” he jokes. “But really, it’s about shared emotions and being empathetic. I want to understand what the animals are thinking and feeling. I try to put myself in their place and look at things from their point of view. Their reactions make sense when you put yourself in that scenario.”

Smith says handling bison is like being in a state of controlled chaos. He emphasizes being quiet and calm around them. Above all, he says, don’t panic. “Learn to flow. The animals will flow like water. Especially in a group, they ebb and flow and you need to do that, too. Don’t go against the flow, but work with it.”

Successful handling is all about getting the animals to go where you want them with the least stress. Pressure is the key to making that happen. “Every movement you make as a handler puts pressure on the bison. Watch your posture. Don’t be aggressive, but don’t be too timid,” explains Smith. “When it comes to eye contact, I feel like they respond when I do that, but again, don’t be aggressive about it.”

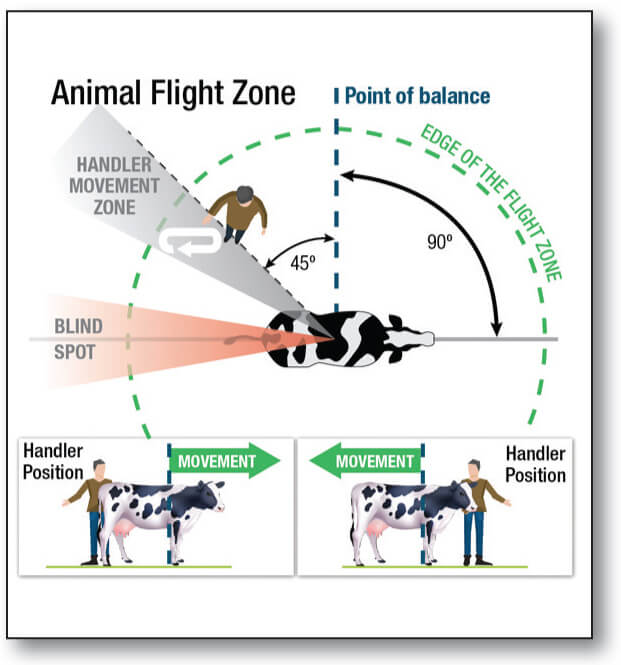

SDSU Flight Zone graphic: Courtesy of South Dakota State University

Understanding the flight zone and that bison have a larger one than domestic livestock is crucial to using pressure.

Temple Grandin, noted author and speaker on autism and animal behavior and professor of Animal Science at Colorado State University, explains the flight zone as that distance from the animal to a threat that causes the animal to begin to move away from the threat. If the threat is outside the flight zone but still “nearby,” the animal will turn and face the threat. As the threat approaches and reaches the boundary of the flight zone, the animal will turn and begin to move away.

Increasing pressure on the animal’s flight zone effectively creates animal movement—however, too much pressure and the animal panics. The optimal handler position is at the boundary of the flight zone. Knowledge of the flight zone allows the handler to manipulate animals in a low-stress manner.

When do you apply pressure? Smith says it’s all about timing. “You use different pressure for different goals,” he explains. “Patience is a virtue when working with bison. Slow IS fast, and you don’t have to make fast moves; keep effective pressure on until they do what you want. Good judgment comes from experience, and much of that comes from bad judgment.

Learn from your mistakes!”

Handlers should use the minimum amount of pressure to invoke the desired response. Slow movements and slight increases in pressure until the animals respond, will create a calm and relatively positive experience for the bison. Be careful not to apply too much pressure, which can cause the animal to panic. Knowing the animal’s flight zone will allow you to manipulate the animals as desired.

Grandin says the biggest handling mistake she sees when running animals through a handling facility is too many animals in the crowd pen. She says when that happens, there is not enough room for the animals to move freely, making it more challenging to get them to move and adding another layer of stress to an already stressful situation. Grandin feels the crowd pen should be at most one-third to half full.

Less crowding also helps alleviate animals becoming aggressive toward each other. She also encourages them not to push animals tightly with the crowding gates. She looks at that gate as the emergency brake. You only need to use it if you have a couple of balky animals that you need to encourage their forward motion by using the gate.

What kind of equipment is needed to work with animals? Not much, and less is better. Smith uses flags and a plastic paddle, with a hot shot being the last resort. “Don’t let the hot shot become your primary tool,” he cautions. “Putting the right people in the right place when working bison is the best tool.”

Tarping pen gates gives the illusion of solid walls, driving the bison toward the open gate or the light.

A sorting stick with a flag or even a plastic bag on the end is usually enough to get the animal’s attention and get them moving. Crazy waving of the flag or bag or yelling is not necessary. Quiet movements and using the flag to guide the animals is the desired action. Sometimes subtle, novel noises such as snapping your fingers, rustling the bag on the end of your sorting stick, or even lightly shaking a few coins in a can will do the trick and get them to move.

Shadows are scary to bison. They prefer to move from dark to light areas and avoid going into dark places like trailers. Using tight tarps to create a solid visual barrier can help encourage animals to find the “light” or the opening to where you want them to go. Handling systems that are tarped or have solid sides offer the illusion of restraint. The bison are less likely to try if they cannot see a place to escape.

Smith touched on another situation where stress heightens if not managed. Loading and transporting bison can be a very trying experience for both the handler and the bison. Working with your hauler ahead of time can significantly reduce the amount of stress and time needed to load the bison. The trucker knows what his trailer can do; defer to their experience when planning a load.

Be transparent and let them know how you think your animals might react when trying to load them. Do your sorting ahead of time in the corrals and not on the trailer. Throughout the process, be flexible and understanding. Your liability ends where the trucker’s begins.

Finally, have a transport safety plan. Things can and do go wrong, so be prepared. Give your hauler contact information for each end of the load so they can inform everyone in case of an emergency or an accident.

Minimizing stress in your bison herd paves the way for healthy, content animals performing well in the pasture, finishing pen, or rail.

Story and Photos by Karen Conley, Communications Director at Bison World (25 years in Bison Industry) Bison World Editor and Advertising Manager, Karen@bisoncentral.com

Reprinted from Bison World, Fall 2023, p26-32. Used with permission from National Bison Association. For more information contact www.BisonCentral.com ((303) 292-2833)

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog

That was so very educational in understanding animal behavior, especially bison. Thanks.