Bison Center Opens in Custer State Park

Rapid City Journal Shalom Baer Gee , May 20, 2022 Updated Jun 25, 2022

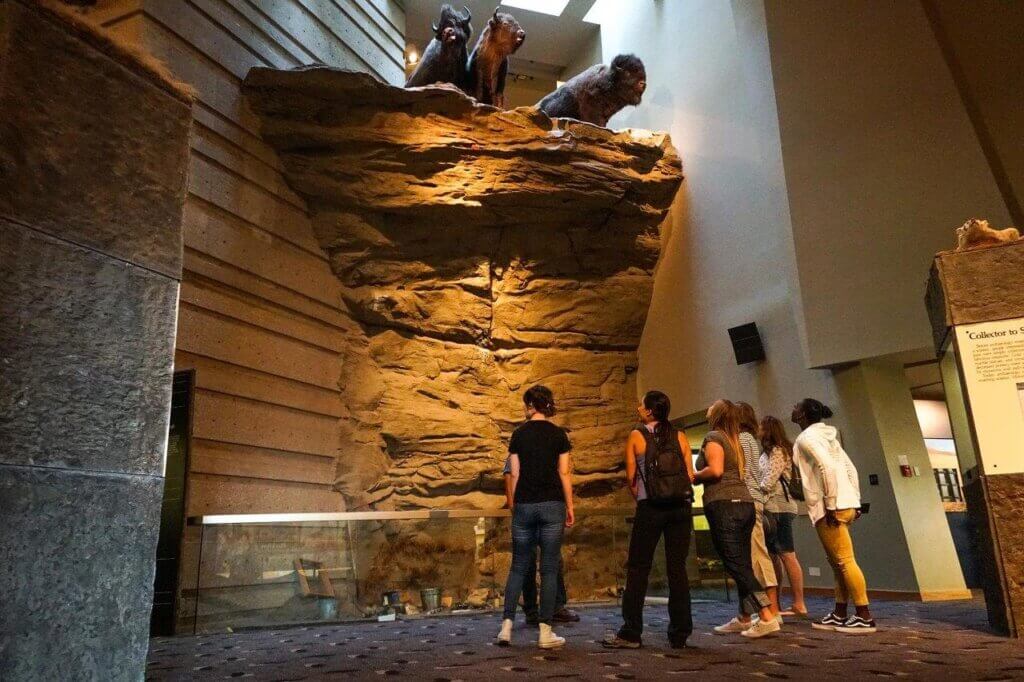

Custer State Park held the ribbon cutting and grand opening of its new $5 million Bison Center on May 20, 2022. Photo by Matt Gade, Rapid City Journal.

About 100 people gathered on Friday for the grand opening of Custer State Park’s Bison Center, located near the bison corral complex off Wildlife Loop Road.

The barn-style building tells the story of the park’s bison herd through a mixture of interactive and educational exhibits, including samples of an American Bison’s summer coat beside a winter coat.

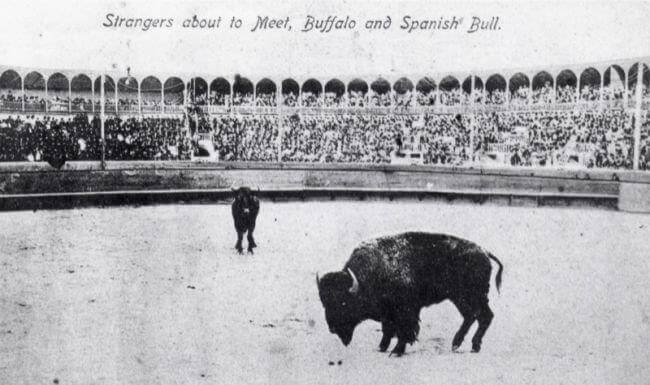

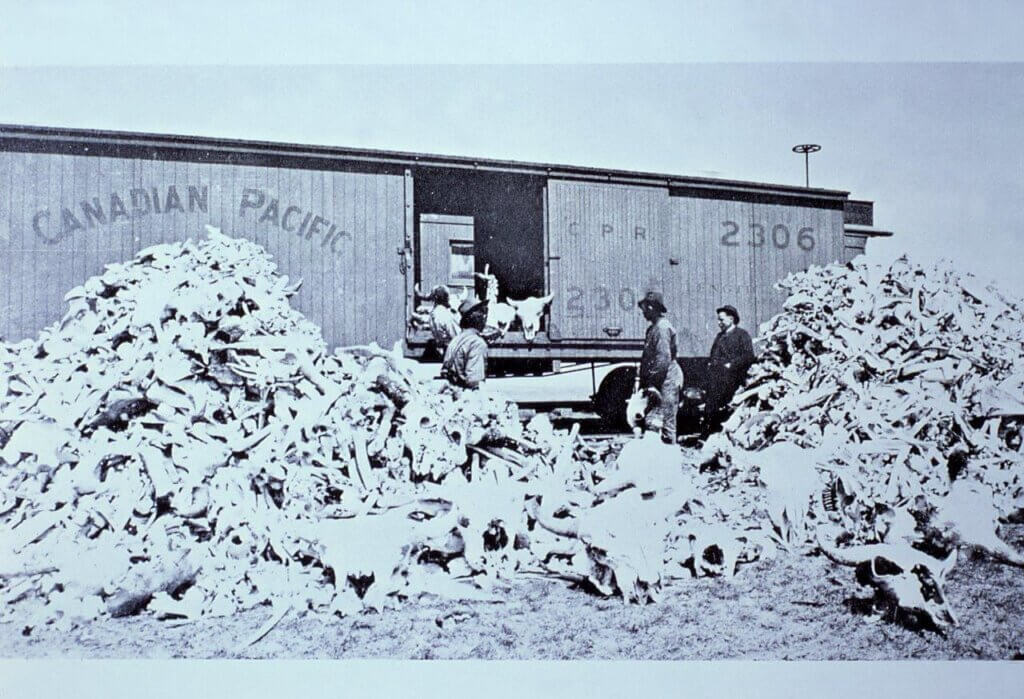

A timeline of the history of bison, specifically the herd of nearly 1,400 that now live in the park, spans the three walls. The herd started at a mere 36.

A computer screen features footage of the annual Buffalo Roundup and Auction where the bison are given health checks, vaccinations and some of the herd is auctioned off to maintain a sustainable population at the park. Several full-body bison mounts also adorn the building.

The center was made possible by a $4 million grant from The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust, $500,000 allocated from the South Dakota Legislature, and an additional $500,000 in private donations raised by the South Dakota Parks and Wildlife Foundation, according to a Custer State Park press release.

Speakers at the event included Lt. Gov. Larry Rhoden; Walter Panzirer, a Trustee for the Helmsley Charitable Trust; Cabinet Secretary of Game, Fish & Parks Kevin Robling; and Custer State Park Superintendent Matt Snyder.

Engaging exhibits tell why the park does a roundup each year and how the bison are managed—from genetic testing, research and range management. Photo by MG, RCJournal.

“I love this park,” said Kevin Robling, Cabinet Secretary of Game, Fish & Parks. “For more than a century, Custer State Park has been known as the state’s crown jewel.

“Today that jewel just got a little bit brighter. We strive to serve and connect people and families to the outdoors, and our vision is to enhance the quality of life for current and future generations, and this facility will do just that.”

Snyder thanked the staff at Game, Fish & Parks in Custer State Park, the state engineer’s office staff, Perspective, Inc. and architectural design studio, Brett Olson and his staff at Mac Construction, Betty Brennan and her staff at Taylor Studios, who designed the interior of the building, and “so many subcontractors who put forth a tremendous effort to see this (happen) quickly.”

“For those who may have been with us last year at the roundup at the end of September (2021), we had a little bit of concrete coming out of the ground, and just a few short months later, look at where we’re standing today. It’s amazing,” Snyder said.

The park’s interpretive programs manager, Lydia Austin, said she and her team worked with the Helmsley Foundation for the building itself, and her team worked together on designing the displays, writing text and photo selection. In the early planning, meetings centered around what type of bison story the new center would tell.

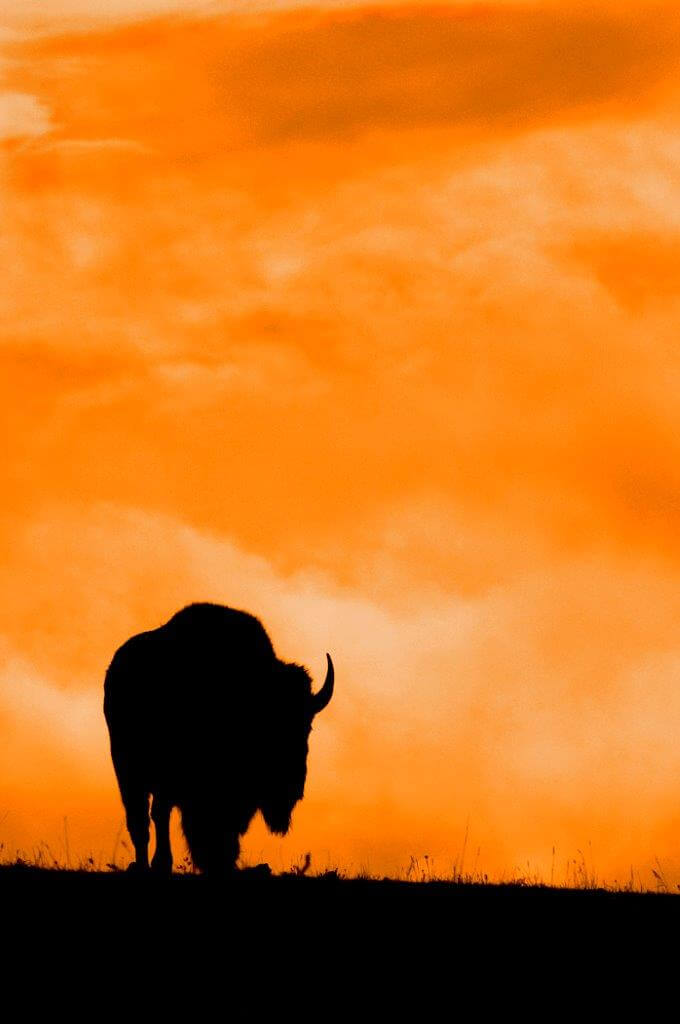

“The bison story is such a huge part of North America. It was hard to take it and reduce it down to our building,” Austin said. “In the end of the conversations, we decided we wanted to tell the story of the Custer State Park herd, how we became a conservation herd, how we still manage our animals. We still protect them for future generations, and we said that was the story we wanted to stick to.”

Small visitor is attracted to a mounted prairie dog and box that speaks. Photo by MG, RCJ.

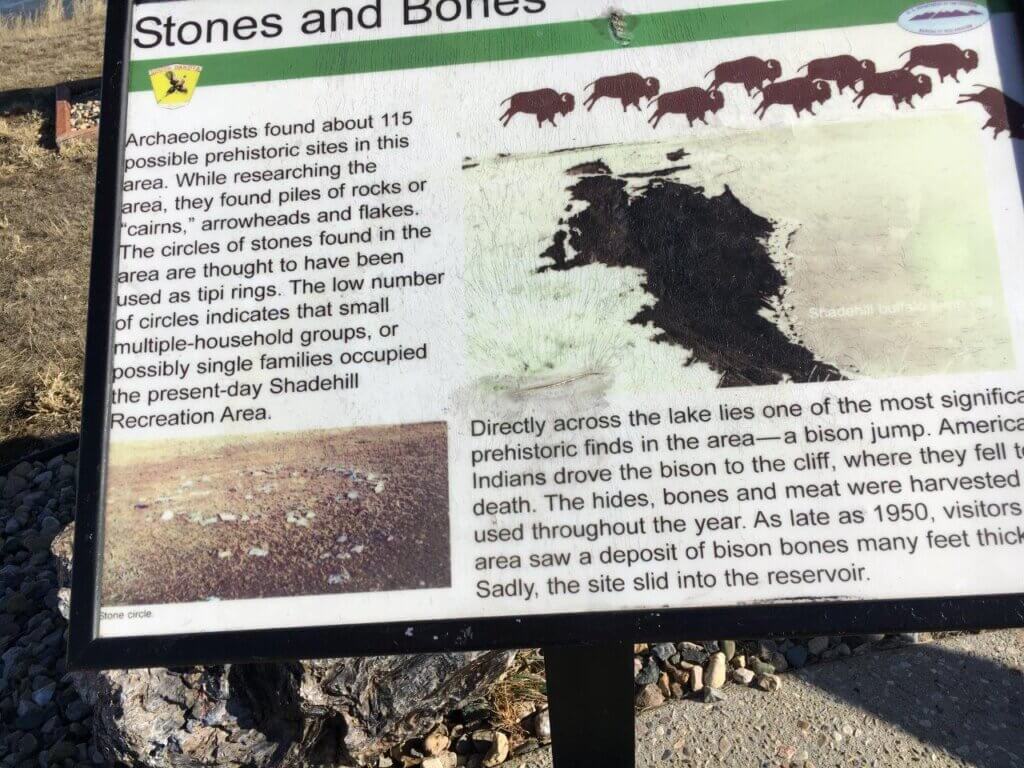

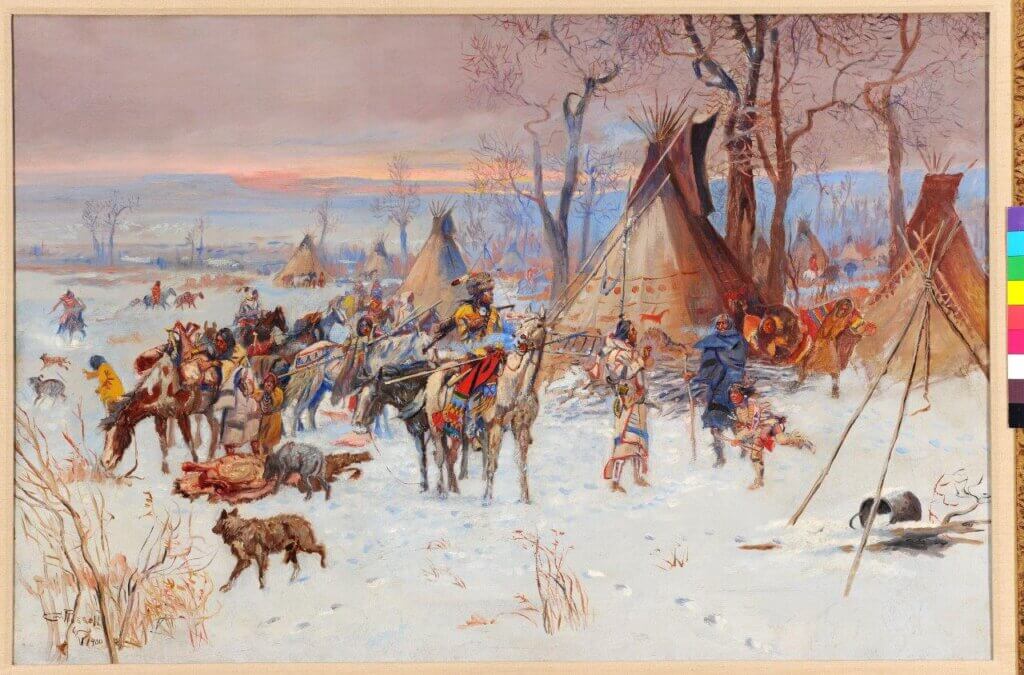

For many Native American cultures, the bison is a significant cultural and spiritual animal. Austin said the park recognizes this, but chose to focus primarily on Custer State Park’s herd. There is a small section on a poster recognizing the significance of bison to Native Americans, but the center doesn’t include materials elaborating on that.

“Buffalo are attached to so many stories. Whose story do we tell? Is it our story to tell? In the end, we really decided we’re going to tell Custer State Park’s story. That’s the one we’re comfortable with, and we know we’re telling the correct story,” Austin said.

A timeline of the history of bison, specifically the herd of nearly 1,400 that now live in the park, spans the three walls. The herd started at a mere 36 from the Scotty Philip herd. Photo by MG, RCJ.

Rhoden spoke at the ribbon cutting. He told the Journal afterwards the center will enhance visitors’ experiences at the buffalo roundup.

A computer screen features footage of the annual Buffalo Roundup and Auction where the bison are given health checks, vaccinations and some of the herd is auctioned off to maintain a sustainable population at the park.

“I think it’s really special because we have tens of thousands of people that come to the roundup. They see the roundup, but they don’t know what’s going on. They don’t know the history behind the buffalo, so this gives them an idea of what it’s all about,” Rhoden said. “The buffalo is such a big part of our culture and heritage in South Dakota that sometimes we tend to forget about it.”

Reprinted with permission from the Rapid City Journal, as reported by Shalom Baer Gee. Photos by Matt Gade, Rapid City Journal.

To the far right on the second photo are the buffalo working chutes and the corral complex—off Wildlife Loop Road— where the new Bison Center is located. Last year at the buffalo roundup only a concrete platform could be seen. Now the new Bison Center is ready for visitors all year long, as well as for the September Roundup. Photos by FM Berg.

For the many hundreds of visitors who come for the Bison Roundup in September and stay for a buffalo dinner and working the smaller herd of bison it may be a long walk to the working chutes. Or if you can easily find your car where you parked on the hills behind where you settled in your lawn chairs, you can drive over to the corrals.

The smaller herd is rounded up and brought in a few days early to familiarize them with the new pasture, which eases them for the stress of being worked and perhaps held too long in the chutes. The larger herd brought in that day on the run needs to calm down a few days before being worked, according to the handlers.

Upcoming events in Custer State Park

- April 18 – May 18, 2023 Knee High Naturalist: Weather

- June 3, 2023

- June 3, 2023 National Trails Day Hike – Climbing Through Geological Time

- June 3, 2023 National Trails Day Hike – Ember History at Sunset

More Comments on Opening Day

“I think some of the unique features of the Bison Center are, one in particular, is just the timeline of how we got bison in the park, you know from 1913 into the current day. That’s always a neat, unique feature,” said Matt Snyder, Custer State Park Superintendent.

“And then we also have a map here in the park that ever since we started the auction back in the early seventies, of where have all the bison gone that have left Custer State Park to start other herds or to supplement other herds. That’s quite an interesting thing too that people like to see.”

“The Bison Center will be a landmark destination for visitors from across South Dakota and around the world to understand the North American bison’s rich history and learn about Custer State Park’s role in preserving this magnificent animal,” said Walter Panzirer, a Trustee for the Helmsley Charitable Trust. “It has been exciting to be part of the project since inception, and I am honored to see it come to fruition with the ribbon cutting and grand opening.”

Lieutenant Governor Larry Rhoden, spoke at the event announcing that he will introduce legislation next year to make bison, the iconic symbol of the American West the official South Dakota state animal.

Snyder said that the center will add to the annual Custer State Park Buffalo Roundup.“Now, after the Roundup, a lot of people leave. Some will come down and see the crowds and watch the bison get work(ed), but now they have another opportunity to come and stay a little bit longer and see the center,” said Snyder. “I think it’s going to aid in educating the public as to what we are really doing and why are we doing what we’re doing,” he said.

Governor Kristi Noem announced the fund raising campaign during the 2020 Custer Bison Roundup.. She said the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust had awarded a $4 million grant to SDPWF to construct the Bison Center.

“Achieving this campaign goal”—(of 5 million dollars)—”will require support from private and public partners who share the dream and vision of the Bison Center. Custer State Park has played a key role in bison conservation for over a century,” she said.

“This one-of-a-kind center will allow the park to tell its story and educate future generations on the importance of the bison. I urge you to support the South Dakota Parks and Wildlife Foundation’s 2020-2021 Custer State Park Bison Center fundraising campaign.”

History of Custer State Park

A timeline of history:

Custer State Park is South Dakota’s first and largest state park. Its history dates back to 1897.

Just 8 years after South Dakota joined the union, Congress granted to the state, sections 16 and 36 in every township as school lands. South Dakota had difficulties attempting to administer the scattered blocks of state school lands within the Black Hills timberland.

In 1906, negotiations opened to exchange the scattered lands for a solid block. In 1910, South Dakota relinquished all rights to 60,000+ acres of timberland within the Black Hills Forest Reserve in exchange for nearly 50,000 acres of forest in Custer County and about 12,000 acres in Harding County.

Together, these two parcels were designated Custer State Forest in 1912. After action by the State Legislature, having been prompted by the urgings of “prairie statesman” Governor Peter Norbeck, Custer State Forest became Custer State Park.

- 1914: 36 Bison purchased from the Scotty Philip’s herd near Pierre

- 1916: 12 pronghorn antelope added

- 1919: On July 1, Custer State Park officially became a state park

- 1921: C.C. Gideon opened the Game Lodge on August 8, it burned on October 19 and was reopened on June 15

- 1922: Needles Highway was completed and 8 Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep were introduced

- 1924: Bison herd totaled 100 animals

- 1925: Badger Clark completed his cabin “Badger Hole”

- 1927: President Calvin Coolidge and Mrs. Coolidge spent three months at the Game Lodge, “Summer White House”

- 1932: The Civilian Conservation Corps completed Iron Mountain Road, connecting State Game Lodge and Mount Rushmore National Monument. The Civilian Conservation Corps completed multiple projects within the park

- 1941: Construction completed on Mount Rushmore. It began in 1927

- 1946: Black Hills Playhouse productions began in a tent near Legion Lake

- 1951: 60 bison purchased from Pine Ridge Indian Reservation herd

- 1953: President Eisenhower visited State Game Lodge

- 1961: Visitation reached 1,000,000 people

- 1966: In February, first live buffalo auction held with 100 animals

- 1979: The park museum and welcome center, built by the Civilian Conservation Corps, dedicated as Peter Norbeck Visitor Center

- 1988: Galena Fire, started by lightning, burned 16,002 acres; 1990: Cicero Peak Fire, spark from logging equipment, burned 4,510 acres inside park, 14,203 acres total; 2017: Legion Lake Fire one of the largest wildfires in SD history.

- 2016: New Visitor Center unveiled

- 2022: Bison Center Opens near the buffalo working chutes and corral complex

________________________________________________________________________

NEXT: Blog 83-How much meat could a Buffalo hunter eat?

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog