When is a Bison Carcass Size Just Right?

A ranch herd: Are adult buffalo larger than they were a few years ago? Or is it just those less than 30 months that are larger?

A new voice at the Center of Excellence for Bison Studies in South Dakota asks a question few people ask.

Dr. Jeff Martin is Assistant Professor of Bison Biology & Management in the Department of Natural Resource Management and the new Extension Bison Specialist stationed at the new SDSU Bison Center of Excellence.

Located at South Dakota’s West River Research & Extension Center in Rapid City, SD, his research is interdisciplinary across wildlife biology, climatology and human dimension. He seeks to answer questions of wildlife conservation and production in a changing world.

Dr. Martin’s research on Buffalo (as a scientist he prefers to call them ‘Bison’) is at the nexus of two paradigms: changing climate and changing cultural values. He attempts to merge understanding of conservation science with direct stakeholder engagement to improve conservation for wildlife across, for example, working ranch herds compared with wildlife parks.

In this article Dr. Martin explores both direct and indirect drivers and consequences of body size change using Great Plains buffalo as a focal species. He notes that since 1980, young steer and heifer cattle carcass sizes have increased 25%, nearly 4 pounds per year, from 673 pounds to 846 pounds.

Bison carcasses have only reported reliable weight data since October 2015, but this still demonstrates an increase in weight over time for males and females by 6% (age less than 30 months), a gain of nearly 5 pounds per year, from 588 pounds to 623 pounds.

What are the consequences of this drive for larger carcasses? Turns out there may be many—some depending on how far south the bison are being raised. Others unexpected. And there are costs.

In the end, Dr Martin leaves us with an unanswered question: When is the size of a Bison carcass ‘Just right?’

A second-generation bison rancher, Martin has personally witnessed how the bison industry has worked together to become more educated on climate change and other pressing issues. “I’m excited to be able to bring in the extensive resources of Extension to help train, problem solve and educate the current and next generation of bison managers,” Martin said.

Below is his “Goldilocks” research paper.

Are ranch buffalo bulls larger than they used to be? Photo courtesy of Vince Gunn.

Goldilocks and Bison Carcass Size Considerations

By Jeff Martin, Assistant Professor and SDSU Extension Bison Specialist

March 24, 2023, SD State University, Brookings SD 57007

Jeff Martin has been named the SDSU Extension Bison Specialist and Assistant Professor of Bison Biology and Management in the Department of Agriculture and Natural Resources. Dr. Martin’s role is 70 percent research and 30 percent Extension, and he will continue to be based at the new West River Research and Extension center in Rapid City, South Dakota. Photo submitted.

Buffalo can thrive on a variety of plains landscapes—whether desert or lush grass. Photo U.S. Dept. of Agriculture.

Most of us are familiar with the childhood story of Goldilocks and the three bears, where the little girl tries to find the bed that wasn’t too hard, nor too soft, but “just right.” This concept can be applied to many facets of life and business.

For livestock, discussions and evaluation of body size, carcass weight and dressing percentage come up regularly. While many strive to have the biggest, thickest or heaviest, these size traits can sometimes lead to production or conformation issues: infertility, sway back, exorbitant health and feed costs, susceptibility to heat stress, etc.

Heat stress in particular is becoming more prevalent, in step with more frequent and longer heat waves, especially on densely populated feed yards in the southern Great Plains.

Are Bison Too Big, Too Small or ‘Just Right’?

Unfortunately, high mortality rate events are becoming more frequent and are associated with prolonged heat wave events. However, heat waves have been around for a while and so have cattle (and bison for that matter). So, are today’s cattle and bison too big, too small, or “just right”?

Meats sourced from bison (Bison bison) and beef cattle (Bos taurus) have long been utilized as protein sources for consumers in North America. However, the systems utilized for bison and beef production vastly differ.

For example, the beef system slaughters on average 28.8 million head per year, whereas the bison system slaughters on average 41,700 head per year. This magnitude of difference is like comparing apples to nuts (and not the edible kind of nuts, but instead nuts for fastening bolts).

Back to the point, population size and body size have tradeoffs: larger body sizes consume more food, therefore, restricting population sizes through carrying capacity coupled stockings rates.

However, body size determines required food intakes, measured as daily minimum dry matter intake (DMI) (Ehlert and Brennan 2021a); there’s a handy little Grazing Calculator to help you with the math (Ehlert and Brennan 2021b).

Stocking rates rely on this static assumption of predictable body size. Stocking rates, measured as animal units (AU), typically use a fixed, static body mass measure (usually around 1,000 pounds of cow/calf pair).

For example, if you have a 1,200-pound cow and a 200-pound calf pair (collectively 1,400 pounds), then you have 1.4 AU per cow/calf pair. Now let’s say you have only 100 AUM of forge available in your pasture for one month.

With 1,000 pounds cow/calf pair (1 AU) you may sustain up to 100 head for a month, however with 1,400 pounds cow/calf pair (1.4 AU), you may only sustain up to 71.4 head for that same month.

Larger body sizes have other tradeoffs: longer lifespan, higher reproduction potential, lower mass-specific metabolism, faster growth rates, higher total digestive intake, higher total manure output, etc.

Larger bodies in heat are presented with yet another math problem: surface area (skin) to volume (body mass) ratio. Body mass scales nearly 1:1 with volume, but only scales at 1:0.67 for surface area. Meaning that, with increasing body mass, there is much less skin (surface area) per unit volume.

This is equivalent to building a Cummins diesel engine and only using a radiator from a Ford Model T, and driving it across the Mojave Desert in summer—it’s going to overheat and fail, because the radiator is too small to dissipate internally generated and absorbed solar heat.

This metaphor applies to the skin of large animals being too small to effectively dissipate heat generated from rumination, metabolism and absorbed solar radiation.

Conventional wisdom suggests that larger bodies produce larger carcasses; therefore, suggesting that you then make more money per animal.

But if you have such larger animals, resulting in increased mortality due to more intense and frequent heat waves and increased feed requirements, do your profit margins actually pencil out?

Trends in Carcass Size

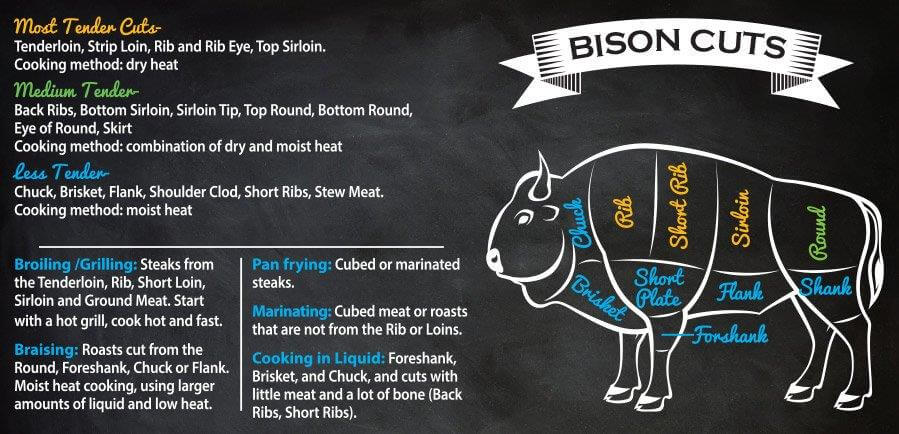

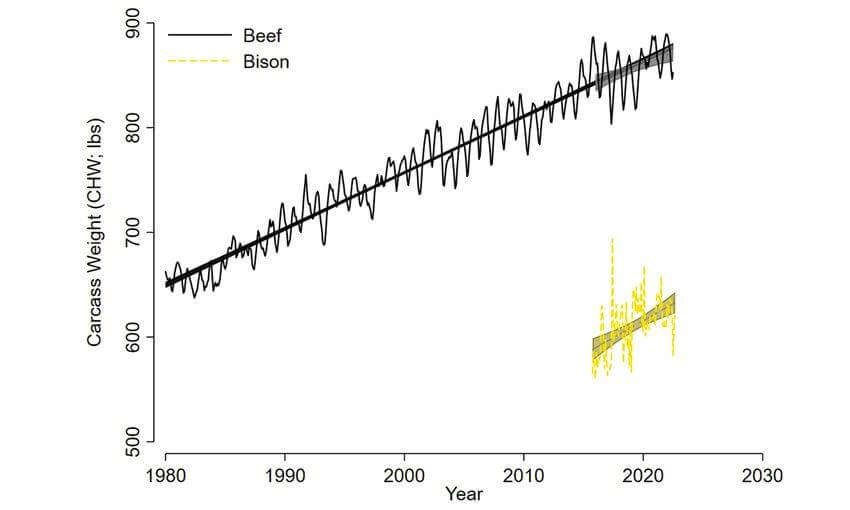

Since 1980, steer and heifer beef cattle carcass sizes have increased 25%, nearly 4 pounds per year, from 673 pounds to 846 pounds (Figure 1; black solid curve and black trend line); a trend that continues from 2015 to present (Figure 1; gray trend line).

Unfortunately, USDA has only reported data reliably for bison carcass weight since October 2015. But this short interval still demonstrates an increase in weight over time for young (e.g. age less than 30 months) males and females by 6%, a gain of nearly 5 pounds per year, from 588 pounds to 623 pounds (Figure 1; yellow dashed line and yellow trend line).

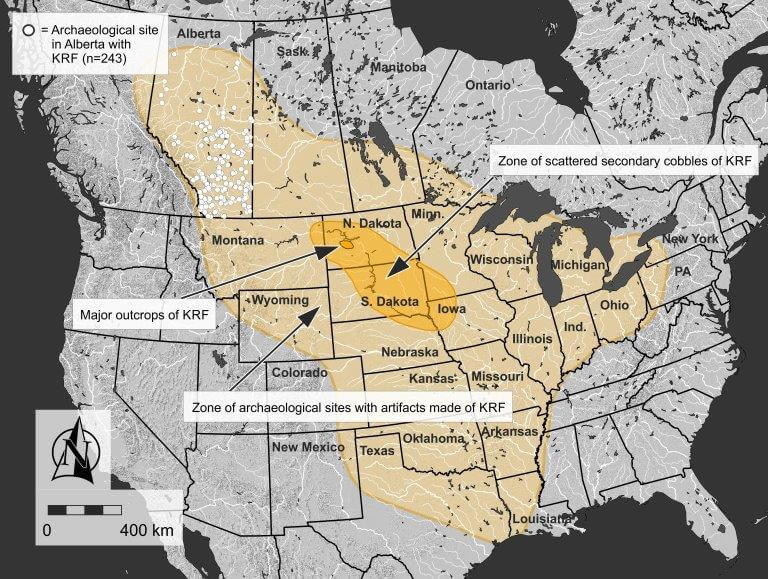

For bison, the increasing carcass size trends described above are counter to observations made about live body size and body mass declining in response to warming and drought in wild and semi-wild herds (Martin and Barboza 2020, Martin and Klemm 2022).

Yet, increasing bison carcass size aligns with processor observations at various processing plants that are challenged to deal with the consequences of carcasses being too large (Conley et al. 2018).

Graph of monthly average cold carcass hanging weight of steer and heifer beef cattle (black solid curve and linear trend line) since 1980; carcass weight of steer and heifer beef cattle since 2015 (gray confidence interval). Yellow dashed curve and yellow linear trend line show young male and female bison (<30 months of age) over monthly average year.

Data are from USDA ERS and USDA NASS (USDA 2016, United States Department of Agriculture 2019) and bison data from SDSU Economics Webtool (Martin et al. 2021).

Is Increasing Bison Size a Benefit?

Yet for beef, the increasing carcass size trends—and associated increasing mortality rates—follow the predictable progression of artificial selection (Klemm and Briske 2021, Martin and Klemm 2022).

This suggests that the private bison sector may be on an unsustainable path heading for even costlier consequences of increasing carcass sizes occurring in parallel with impending heat waves, droughts and other extreme weather events. It behooves managers in the private sector to reconsider the trajectory bison body size is going.

In fact, to counter large carcass sizes, many bison processors already apply oversize carcass penalties in the form of lesser dollars per pound. Processor issues are related to diminished cutting efficiency and carcasses potentially dragging on the floor.

Similarly, if the surprise for Goldilocks was that she woke up in a house full of bears—then the surprise for managers with larger carcass sizes is that larger animals living on the range and in finishing lots struggle to survive heat stress.

Looks like this Grandma cow is headed somewhere—maybe through a weakness in the fence or a gate left open. The others will follow in her wake, eager to get back on grass. Photo by Donna Keller.

References

- Conley, K., B. Dineen, B. Anderson, M. Jacobson, and D. Gehring. 2018. Is a bigger carcass really better?. National Bison Association. Bison World 4:14–19. Westminster, Colorado.

- Ehlert, K., and J. Brennan. 2021a. The Importance of Math in the Art of Grazing. Brookings, South Dakota.

- Ehlert, K., and J. Brennan. 2021b. Grazing Calculator. Brookings, South Dakota.

- Klemm, T., and D. D. Briske. 2021. Retrospective Assessment of Beef Cow Numbers to Climate Variability Throughout the U.S. Great Plains. Rangeland Ecology & Management 78:273–280.

- Martin, J. M., and P. S. Barboza. 2020. Decadal heat and drought drive body size of North American bison (Bison bison) along the Great Plains. Ecology and Evolution 10:336–349.

- Martin, J. M., and T. Klemm. 2022. Climate Change Impacts on Large-Bodied Grazing Ruminants and Forage Grazing. C. Miller Hesed and H. Yocum, editors. Synthesis of Climate & Ecological Science to Support Grassland Management Priorities in the North Central Region. United States Geological Survey, Fort Collins, Colorado.

- Martin, J. M., H. Menendez III, and J. Brennan. 2021. Bison Economics Tool. South Dakota State University Extension 1–3.

- United States Department of Agriculture. 2019. 2017 Census of agriculture United States summary and state data. Accessed 21 Jun 2019.

- USDA. 2016. Overview of the United States Cattle Industry. USDA, National Agricultural Statistics Services 1–19.

Contact Dr. Jeff Martin:

SDSU West River Ag Center

Bison Center for Excellence

711 N Creek Drive

Rapid City, SD 57703

605-394-2236; 1-605-688-4792

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog