Buffalo Trucking for 24 Years

Tim Omilusik is a 42-year-old Canadian trucker from Coronation, Alberta, who runs a short- and long-haul livestock business from one end of Canada to the other, with 2,000-mile trips across the border down into Texas in between—or maybe a leg to Missouri or Wyoming.

Bison loads preferred. In fact, he says, he now hauls only buffalo to the USA.

Omilusik shares his bison-moving adventures on Twitter. A man of few words—Twitter is an ideal platform for him.

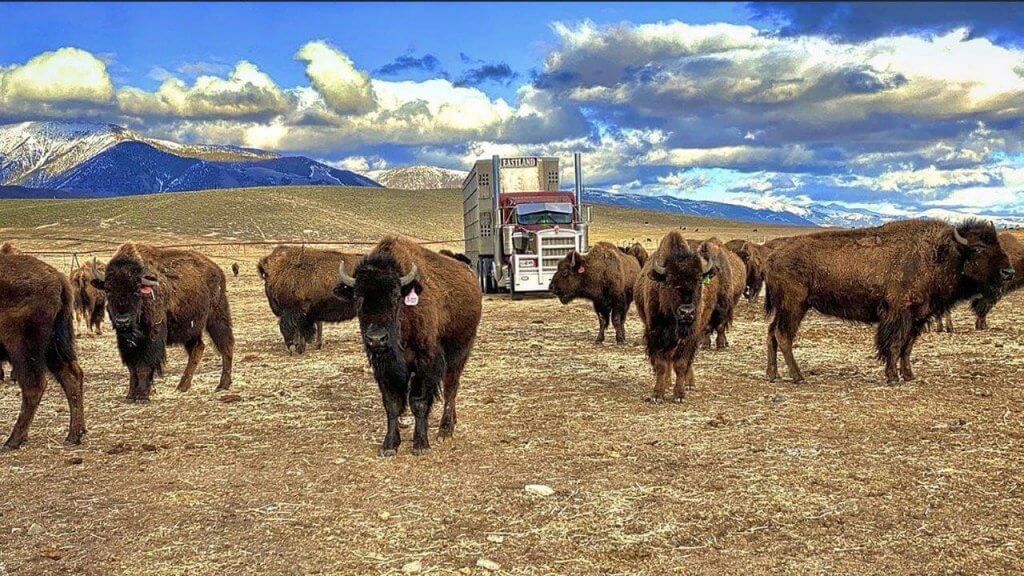

Omilusik shares his bison-moving adventures on Twitter. Bison loads preferred. Photo courtesy of Tim Omilusik.

“Bunch of beauties!

“Oh my goodness. These are big boys.

“Majestic!

“Beautiful set of bull calves. Very quiet. It was a long journey for them.

“Speedy ladies…..Don’t matter how fast you think you are, you ain’t beating no bison. So incredibly athletic”

There’s an appreciation for the scenery:

“You can’t beat the fresh mountain air.

“Scenic rip through Montana

“Idaho skies.” A brilliant sunrise—or sunset.

On some days he only gives his viewer-readers a video—no words.

Sure enough, a video tells it all.

He provides great movies of buffalo charging into the big trailer—with large grunting, groaning sound effects.

Oh my goodness. These are big boys. pic.twitter.com/5lziLd5eFI

— Eastland Transport Ltd (@eastland09) April 14, 2021

Big bulls duck their gigantic heads to avoid scraping the ceiling—as they lunge up or down a ramp to other decks. Credit TO.

Big bulls duck their big heads to avoid scraping the ceiling—as they lunge up or down a ramp to another deck.

Now and then it’s a startled-looking gang of youthful horned heads standing together. Loaded, but turned back toward you—the viewer—as if wondering whether a full charge out the back door might succeed.

Omilusik apparently lets them know in a calm way that’s not going to work. From a corner of the camera you see a wave of his flag-on-a-long-stick—and he swings shut a divider gate.

Sometimes there’s a ‘thank you’ from a happy customer:

“Announcing the arrival of a lovely group of 23 Canadian bison heifer calves from Wolverine Bison. This has been a long journey from the seed of an idea a year ago to their arrival today. Special thanks—Tim from Eastland Transport Ltd. who safely transported these bison calves all the way from Saskatchewan—and was totally amazing during the unload!”

Sometimes Tim’s videos show the buffalo running full-tilt out of the trailer.

Or—already unloaded—they are investigating a new green pasture, a corral or galloping through a long narrow chute.

Omilusik’s big new truck might be washed shiny clean and brilliant red in the sunshine, cruising toward home.

Or it might have the full load of a long trip, splashed with mud, manure, and gobs of buffalo hair bristling out the airholes.

At times it’s just a video of a narrow highway, running ahead of that bright red truck hood taking the curves down a mountain road through Black Hills pine trees—Hiway 85, the scenic route back home to Alberta, I think.

Yes, this is a man of few words—and yet, he’s not. Just get him started on his favorite subject—Bison.

Omilusik Loves his Bison

“I just love them,” he’ll say. And you know he’s grinning into the phone.

“They are so big. So majestic, so strong. Magnificent!

“It’s awesome to see Bison walking the land again.”

“I just love their nature. Their strength. Bison move at full strength all the time. Always going at full speed. You really have to be on your game.

“It’s 40 miles an hour coming on to the trailer. And 40 miles an hour coming off.

‘It’s not something somebody can do alone. It takes a good group of people.”

Tim likes to work alone inside the trailer. And outside, just a few people who know what they’re doing—not many just standing around.

Stout bull buffalo horns broke through the side of the trailer one day, and the bull could have escaped—ripped it like a tin can, Tim says. But he did not. “Never had nothing come out yet,” he chuckles. TO

“That’s what happened one time.” When a bull buffalo smashed out a hole in the side of the trailer.

“Too many people working the outside got ahead of the bull and seeing them he spooked while I was trying to close the gate.”

He definitely prefers working alone inside the trailer when loading or unloading. It helps keep “these animals’ stress level at a minimum—better for the Bison.”

“Beautiful set of bull calves. Very quiet. First time on a truck an very little pressure to load an pretty much open the gate an they walked out behind me to unload.”

He loads them up—in the video you can see Tim’s boot and half a leg as he waves his flag—and deftly swings the divider gate at the same time.

Can that be a grocery-store plastic bag on the end of the long stick he’s waving?

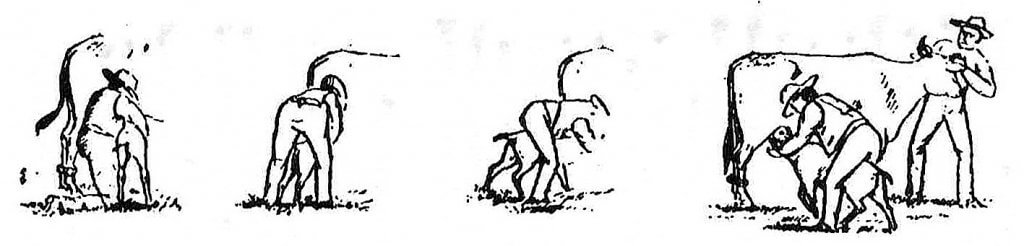

He dips his head to the lower gate as a ‘Load of little ladies’ heads down a ramp into the front ‘Nose.’

A final wave and sweep of the plastic flag, shut the gate, and one more compartment is loaded and ready to go.

Can’t beat the 2 stage nose option. With it Set in the fat rail position ,it’s an easy in an out low stress operation. Works great ! pic.twitter.com/uQfMH3Xuqf

— Eastland Transport Ltd (@eastland09) May 27, 2021

Tim Omilusik calls riding in his truck, driving a load of yearlings or the big guys, being in his Happy Place. TO.

Riding his truck, driving a load of yearlings or maybe ‘the big guys.’ Getting out on the open road that stretches ahead for hundreds of miles—travelling south, east or west. That’s being in a happy place.

Winter Driving and Icy Roads

And yes, there’s some winter driving in January. Of course, there is, when you live 10.5 hours north of Minot, ND, with a full load of Bison and a huge truck!

On Jan 14, 2021, he shared: “Never have I ever felt the true force of the wind until last night. I’m loaded in this pic, parked. Highway is a sheet of ice. The wind literally blew my trailer sideways towards the shoulder. Scary stuff.”

He’s realistic. Frustrated, probably, but mostly concerned about those buffalo on the trailer. What’s best for them?

“I was NE bound–but forced to turn back.”

On March 17, “Wyoming got hit hard. Interstate I25 finally opened. I only was shut down for 12 hours but lots of trucks had been parked since Saturday when the storm hit.”

Another time he writes, “Been sitting at the truck stop for 2 days waiting for Sunday to load and I’m getting bored.

‘I had a close call a few years ago at a rest area in Montana. I was coming out of the restroom and caught a couple of animal rights activists trying to open the liftgate on my trailer and release the bison. They figured what I was doing was cruel and they should be set free to roam.

“After a heated argument, they got into their car and drove away.

“Now I padlock every door and gate to keep that from happening. Somebody could have been seriously injured or even killed.

“They had no idea what they were dealing with or the situation they were putting themselves and others in.

One day an insurance agent friend tells him about a retired veterinarian who was awarded a medal for bravery. He had fought off a bison bull who had another fellow down in a chute and dragged that fellow to safety.

Tim’s comment, “Very lucky he was there to help.”

Tim’s a bit reticent about who and where he’s serving his clientele—which I expect, many bison ranchers appreciate.

He gets the load where it’s going in the best shape possible, and no complaints.

His 2013 Kenworth Truck

I first encountered Tim Omilusik last year on the internet when John Hitch, editor of the magazine ‘American Trucker’ wrote an article on a ‘Day In The Life Of A Bison Hauler,’ featuring his work, dated Oct 21, 2020.

Turned out to be more than one day. In fact, Omilusik has been doing this for 24 years, and he told Hitch he learns something new every day when working with Bison.

Readers of the trucking magazine, of course, wanted to know about the kind of truck he drove—and the big trailer he hauled behind.

“What’s your current truck-trailer set up?” asked Editor Hitch.

“A 2013 Kenworth W900L. I ordered it brand new September of 2012. It was my first truck with a DPF (diesel particulate filter) on it. It took a little bit to get used to. It is equipped with a Cummins 550 ISX/1850 torque.

“I’ve had Cummins all my life and was pretty impressed with the performance of the new emission engine. I have got just under 950,000 miles on it.

“I’ve spec’d out a new truck, but with the way the economy is and the new prices, it’s pretty scary to jump into a new one. A truck I spec’d a little while ago came in at $265,000 Canadian (US $219,685). That’s just a lot of money.

As for the big trailer: “I have a 2017 Merrick quad-axle trailer—built a little bit heavier than your typical regular livestock trailer. It’s still pretty weak when it comes to hauling bison.”

A New Truck in Viper Red

But that was last year.

Since then Omilusik has upgraded to a new 2022 Peterbilt 389-special truck.

After all, he had driven his 2013 Kenworth nearly a million miles in less than 9 years—a total of 950,000 miles.

He ordered the new one in December—in a bright shiny red—a color called ‘Viper Red,’ his father’s favorite color—purchased in his honor, he says.

Tim ordered his new 2022 Peterbilt 389-Special in Viper Red—his father’s favorite color. Here it’s hooked up to his ‘Mobile Barn’ and ready to pick up a load of Bison. He can haul 100 feeder calves or about half that many cows at once. TO.

For a time in March Tim was between trucks. His old one was sold. The new one hadn’t arrived.

“8.5 years of my life I put into driving this truck and now she’s on her way to the new owner. I’m impatiently waiting to get into my other one so we can start some new miles.”

On April 7, 2021 the truck arrives, and he reports, “We are back in action!! Time to make some miles.”

A few days later the trailer—which Tim refers to as his ‘Mobile Barn’–is attached and ready to roll.

“I think it looks pretty darn good hooked up to the mobile barn.”

Next day he’s off. “Wow !! I missed this.”

A Day in the Life of a Buffalo Hauler

So what’s a day like in the life of a Bison hauler?

“Lots of prep work. I’ll get up, do my precheck, and get myself psyched up for the day. Hauling bison is no easy task.

“It’s a lot different than just hauling regular cattle. They’re quite a bit bigger and more aggressive and can cause quite a bit of damage to you, themselves and each other.

“You need to be calm and cool about it. Relax and have a plan in your head if something goes wrong.

“For instance, one night I stopped just north of the U.S. for a morning border crossing. I had a lot of bulls on, and they started fighting in the trailer. I was up all night keeping an eye on all the bison so they wouldn’t tear my trailer apart.

“I’ll haul slaughter bison or fats used for meat, most of which are to packing plants in Canada or the U.S.

“I haul feeder bison to feedlots and breeding stock all over as well. I have done some stuff for the Canadian government that was for scientific research, such as tuberculosis testing in bison.

“One load will be 55,000 to 60,000 lbs.

“You can get about 100 feeder calves on board or 45 to 50 fats at 1,200 lbs. each. Most runs usually take a few days to complete.

Tim Omilusik prefers working alone inside the trailer when loading or unloading. It’s better for the Bison, he says. It helps keep stress levels down. Credit TO.

“If I load in Canada, it’s a day to the border and then another one or two to the destination.

“USDA law mandates the time the animals can be on the trailer is 28 hours before they have to be unloaded for feed an water.”

Canada has similar rules.

“These runs could be short or long. I’ve hauled bison up to 2,000 miles on one trip. It can be a pretty stressful ordeal.

“I’ve also brought yak from the U.S. over the years. I had to quarantine them on the trailer for three days. They’re smaller, but a little more intimidating because their horns are so much longer.

“14 deer 1 moose. Driving wide eyed !!”

Partitioning the Load

Tim tells me that his latest trailer with two decks can divide into 6 or 7 compartments, depending on what he’s hauling.

“I try to load the same weights together. We never load buffalo of different sizes in one compartment—they would just kill each other.”

“I load the top first—depends on how the trailers are set up. For some in the Nose—the front compartment, which is a little narrower—they have to go down a ramp to get there.

“The Nose can also be in 2 decks—so they might go up or down a ramp. For big animals there’s only 1 level in the nose. For smaller animals of 400 to 700 pounds, it’s a double layer in the nose.

“The ‘dog house’ is on the back end.”

If the bison have been living together they have already established their ‘pecking order’ and they usually get along fine, he says.

“Recently I took a big load of 25 bigger bulls—from 3 different herds—2,000 to 2500 pounds. Put them together in smaller bunches.

“I have several dividers—can make 6 or 7 partitions in 2 decks. I had 3 in one pen in the nose, 4 in another, 5 and then 6.

“It went really good, smoothly.

“Some compartments are smaller than others on the trailer, so you have to watch where you place them. You could really run out of room before you can get them all on.

“Hauling Bison is a lot different than hauling cattle. Bigger, more aggressive and can cause quite a bit of damage to you, themselves and each other.” TO.

A reader asks, “If you end up with the least dominant one last and it won’t go into a compartment do you swap it out or ever just give up on filling the compartment?”

“I have never had to give up. Patience always seems to work,” Tim replies.

“If I have cows and small calves—I separate them into different compartments.

“I have never had any issues with bulls but cows seem to get pretty aggressive with one another.”

He loads them up. In the video you can see a boot and half-leg of Tim Omilusic waving his long-handled flag—and swinging the divider gate.

He dips his head to the lower gate as a ‘Load of little Ladies’ head down a ramp into the front Nose.

A final sweep of the flag, shut the gate and one more compartment loaded.

Then they are off. Mostly things go smoothly.

“These guys escaped an been hiding in the bush for quite some time before being caught. Loaded up an hauled out. They were very unhappy.

“This load of bulls this week definitely were a little on the wild side. No respect for anything. Kept me on my toes.”

The trailer looks strong and well built, and is re-enforced. But with the size and strength of the big bulls, Tim says they could smash through and get out if they really wanted to.

“One time when I was hauling herd bison weighing just under 3,000 pounds, a big bull didn’t like me on the roof an tore a hole through it trying to get at me.”

Tim was unloading from the roof, prodding with his flag to get one pen to leave the trailer.

“He ripped through the roof like it was a tin can. His horn came through right by my foot. A big hole—he could have come right through it.

“Bison horns have the strength to rip open even a re-enforced trailer like a tin can, so staying alert is key to staying safe for a bison hauler, Tim Omilusik warns.

“Never had nothing come out yet, though.

“Occasionally a ruckus is going on the the trailer.”

What do you do then? I wondered.

“Really can’t do anything. Usually there’s less fighting if you just keep going.”

Watering and Feeding Hay

“Feed and water can be a problem. You can’t unload bison and then load them up again. You can do that with cattle, but not bison.

“Their welfare is all I care about. I worry about the welfare of the animals. How to get them to their destination an unload safely

“On super long trips we have 2 drivers.

“If I think it’s going to be a problem I take a long garden hose, tubs for water and connect to a hydrant.

“Tubs are about the size of a half 50 gallon drum—I usually tie them to the walls so they can’t tip. All that has to be put together before leaving home.

“It’s a lot of work. I took a load to Missouri where we didn’t have access. I had to have hay and water. Setting all that up before we leave, it’s just a lot of work.

When they stop he tries to fill the animals up. They can also drink while travelling.

Sleeping in the Truck

“I always sleep in the truck—the trailer is behind, but they move around a lot more when we’re stopped. It all depends on their mood. Sometimes they are good. Other times they will thrash around the whole time.

“After 24 years of trucking you get used to it. Sometimes I stick in ear plugs.

“You definitely feel the movement with the larger ones. Most of the time they are pretty calm. It’s when you get stopped, there can be trouble.

“The animals mostly are bumping the walls and when you stop, they kick a lot and bump the walls.

“Little calves just weaned—300 to 500 pounds—they are agitated and paw the floor a lot.

“Buffalo carry their head low and sometimes one gets stuck between another animal’s legs. Sometimes they can get all tangled up together.

“Just gotta stop, use flags to split them up—usually just a couple animals together, but sometimes more. Need to reposition them.

“Bison are very smart—If one is tired they position themselves against the wall to lie down—out of the way. Where they have room to lie down.

“You learn something new every day when you’re working with bison. It’s a job that takes focus and patience. You always have to be alert and ready for anything.

“These runs could be short or long. I’ve hauled bison up to 2,000 miles on one trip. It can be a pretty stressful ordeal.”

At the end of the run, he reports a delicious meal.

“Friday night supper in the truck. Bison tenderloin compliments of my good friends of Bison Coulee Contracting. Baked potato, broccoli and a salad. I’m going to sleep well tonight!”

When Buffalo Don’t Want to Get Out

Then sometimes he arrives at the destination and the bison don’t want to leave the truck.

“On a long haul they get attached to their surroundings and sometimes they don’t want to get out.

“It’s happened to me three times this year with big herd bulls—they didn’t want to get out.

“Bison have their own mindset. If they don’t want to go, they’re not going to go. You can’t really force them.

And they have to come off the trailer in reverse order of the way they entered, right? One pen at a time? Right.

“Get off the ones you can. I went to bed in the truck with the trailer backed up to the unloading chute.

“You get whatever sleep you can. Some of them will walk off in the night, others early morning when it gets light and they can see where they’re going.”

“I love them to death, so much it’s hard to describe. They are a magnificent animal, so awesome.”

What age do you like the most, I asked Tim. The young ones? The big bulls? The grumpy old bulls?

“All of them. I like them all. The little calves right up to the big guys.

“The little red dogs—(as they call the newborns)—so frisky. I get to watch them bound around, so exciting to watch. How can you not just sit there and watch them?

“And the big guys—I’m just astonished how big and how strong they are. I love hauling them.

“Load of little ladies,” is his verbal output for one day.

“It’s a stressful job, yet it’s very enjoyable for me. Their welfare is all I care about.

“Hauling bison is no easy task.

“Once in a while I have to haul cattle—usually in the spring. But I’d rather just haul bison.

“I’d move them 365 days a year if I could, but it’s seasonal work.

Tim cleans his trailer after every load—to keep down any spread of disease. He’s usually alone for the job, wielding a shovel, bar and pitchfork.

And no, it’s not just manure and wood chips.

There’s more. There’s the hair, coming off in huge clumps in the spring.

Buffalo shed winter hair in huge clumps in spring. TO.

Yes the Hair!

How does he clean buffalo hair out of the truck?

“It can be pretty overwhelming. During shedding season, you have more hair in the trailer than wood shavings or straw. I’ll find a place to shovel out everything and then find a washout [with a hydrant] to finish the cleaning.

“There’s usually so much hair it plugs up their system. I have been kicked out of more places than I can count.”

“The buffalo shed worst in spring. Yearlings and adults shed the most hair. And then they are also stressed from getting loaded in the transport trailer, so they rub on the walls. Not so much the calves.”

Some of his Twitter comments about hair:

“Shedding season. There will be more hair in the trailer than shavings when I’m unloaded.

“More hair than shavings on the floor by the end of the trip.

“Aftermath of hauling bison in the spring. Hair for days. Most loads during shedding season will leave more hair than there will be manure an shavings.

“And this is why washouts don’t like me coming around.”

“Get a leaf blower,” suggests one reader.

He rejects that with a genial, “Haha ya right. It’s packed in like concrete. Hence the pitchfork.”

And later: “Concrete. Exactly why it was used for many building projects for ages—hair, dung, straw.”

He’s right. I’ve seen those early homes in our Ukrainian communities! Hair, dung, straw and mud. Who knew you could build a home with that kind of ‘lumber?’ They did. And some are still standing—after more than a hundred years!

Wow !! I missed this. Happy to be back in my happy place. pic.twitter.com/ps0lqn4klJ

— Eastland Transport Ltd (@eastland09) April 13, 2021

Beautiful set of bull calves. Very quiet. First time on a truck an very little pressure to load an pretty much open the gate an they walked out behind me to unload. TO.

How Tim got Started Trucking

Tim explains how he got into trucking:

“After high school, I wanted to be a cowboy and started working on a feed lot close to home.

“They had their own truck and trailer, and they needed an extra driver, so I got my commercial driver’s license in 1998 and started driving an old 1980s Ford LTL 9000 and pulling a Wilson 50-ft. tandem.

“I did that for a couple of years.

“There was a commercial cattle hauler back home in Alberta. He had three trucks and I started working for him. and it took off from there.

“I just loved it. I got my first truck in 2009 and pulled as a lease operator until I got my own in 2010. I hauled cattle for quite a few years and hauled bison in between.”

Today Tim Omilusik owns the trucking company—Eastland Transport. He also has a wife and a 15-year old daughter who are involved in the business.

His daughter is into 4-H and Rodeo. She’s feeling somewhat disappointed right now because of Covid-19 restrictions and cancellations, which are still widespread throughout Canada. (I wish her many successful shows. As a former 4-H Leader and Extension Agent, I know how hard these kids work and what the shows mean to them. It takes patience—she will get through this and things will soon be better!)

Tim owns no buffalo, but would like to. “Maybe when I retire. Like to have a herd someday, maybe—20 to 50 cows.

“Every year is different—summer months trucking tends to dry up some until fall.

“Feed prices are so high this year—corn prices—that hurts the livestock feeders

Tough to feed animals—When that changes, more animals will be moving.”

Finally, there’s a photo of Tim’s shiny new red truck proudly parked, clean and ready to go again.

“Wow !! I missed this. Happy to be back in my happy place.” TO.

“Ah. That’s looks better. The bugs were starting to take control.

“Washed up. Washed out. Ready to rock n roll in the morning!”

Next day he’s off.

“Wow !! I missed this. Happy to be back in my happy place.”

And off goes Tim Omilusik in a clean truck to pick up another load of Bison.

All’s well in his Happy Place.

(Twitter @eastland09) Eastland Transport Ltd. Is for “Hire’ for all your Bison hauling needs locally and or long distance Canada or the USA. People can reach out to me at

Eastland Transport Ltd; Box 817; Coronation, Alberta Canada; T0C 1C0. Cell Phone: 1-403-578-8705. Email: eastland.transport09@yahoo.ca

—

Next: Secrets of the Buffalo Jump

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog

White Buffalo Calf Woman Brings Gifts, as told by Lame Deer

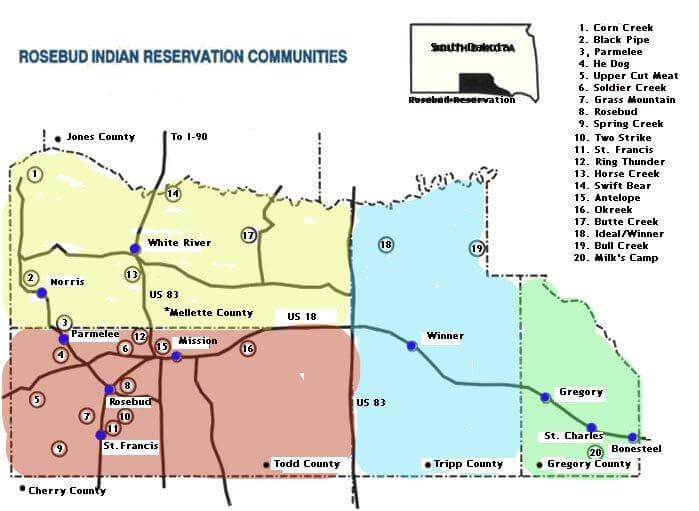

There are many versions of the White Buffalo Woman tradition, passed down in the Lakota Sioux culture from one storyteller to another. This version was told by John Fire Lame Deer at Winner on the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota, 1967. Although the White Buffalo Woman tradition differs in details, at its core it is the same—and each telling adds yet another layer of beauty to the traditional story.

Storytelling was an important way Native traditions and history were passed down through the generations. John Fire Lame Deer told of the White Buffalo Calf Woman tradition at a gathering in Winner in 1967.

One summer so long ago that nobody knows how long, the Oceti-Sakowin, the seven sacred council fires of the Lakota Oyate, the nation, came together and camped.

The sun shone all the time, but there was no game and the people were starving. Every day they sent scouts to look for game, but the scouts could find nothing.

Among the bands assembled were the Itazipcho, the Without-Bows, who had their own camp circle under their chief, Standing Hollow Horn.

Early one morning Chief Standing Hollow Horn sent two of his young men to hunt for game.

They went on foot, because at that time the Sioux didn’t yet have horses. They searched everywhere but could find nothing.

Seeing a high hill, they decided to climb it so they could look over the whole country. Halfway up, they saw something coming toward them from far off, but the figure was floating instead of walking.

Map of the Rosebud Reservation communities covers four counties in South Dakota. At a 1967 gathering in the town of Winner, Tripp County, John Fire Lame Deer told of the White Buffalo Calf Woman tradition on the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota.

From this they knew that the person was “wakan”—or holy.

At first they could make out only a small moving speck and had to squint to see that it was a human form. But as it came nearer, they realized that it was a beautiful young woman, more beautiful than any they had ever seen, with two round, red dots of face paint on her cheeks.

She wore a wonderful white buckskin outfit, tanned until it shone a long way off in the sun. It was embroidered with sacred and marvelous designs of porcupine quill, in radiant colors no ordinary woman could have made.

This wakan stranger was Ptesan-Wi, White Buffalo Calf Woman.

In her hands she carried a large bundle and a fan of sage leaves. She wore her blue-black hair loose except for a strand at the left side, which was tied up with buffalo fur. Her eyes shone dark and sparkling, with great power in them.

The two men looked at her with mouths open. One was overawed, but the other desired her body and stretched his hand out to touch her.

This woman was ‘lila wakan,’ very sacred, and could not be treated with disrespect.

Lightning instantly struck the brash young man and burned him up, so that only a small heap of blackened bones was left. Or some say that he was suddenly covered by a cloud, and within it he was eaten up by snakes that left only his skeleton, just as a man can be eaten up by lust.

To the other scout who had behaved well, the White Buffalo Calf Woman said, “Good things I am bringing, something holy to your nation. A message I carry for your people from the buffalo nation.

“Go back to the camp and tell your people to prepare for my coming. Tell your chief to put up a medicine lodge with 24 poles. Let it be made holy for my coming.”

This young hunter returned to the camp. He told the chief, he told the people, what the sacred woman had commanded.

The chief told the ‘eyapaha,’ the crier.

And the crier went through the camp circle calling: “Someone sacred is coming. A holy woman approaches. Make all things ready for her.”

So the people put up the big medicine tepee with 24 poles and waited. After four days they saw the White Buffalo Calf Woman approaching, carrying her bundle before her.

Her wonderful white buckskin dress shone from afar. The chief, Standing Hollow Horn, invited her to enter the medicine lodge. She went in and circled the interior in the direction the sun moves through the sky.

The chief addressed her respectfully, saying: “Sister, we are glad you have come to instruct us.”

She told him what she wanted done. In the center of the tepee they were to put an ‘owanka wakan,’ a sacred altar, made of red earth, with a buffalo skull and a three- stick rack for a holy thing she was bringing.

They did as she directed, and she traced a design with her finger on the smoothed earth of the altar.

She showed them how to do all this, then circled the lodge again in the same direction. Halting before the chief, she now opened the bundle. The holy thing it contained was ‘chanunpa,’ the sacred pipe.

She held it out to the people and let them look at it. She was grasping the stem with her right hand and the bowl with her left, and thus the pipe has been held ever since.

Again the chief spoke, saying: “Sister, we are glad. We have had no meat for some time. All we can give you is water.”

They dipped some ‘wacanga,’ sweet grass, into a skin bag of water and gave it to her, and to this day the people dip sweet grass or an eagle wing in water and sprinkle it on a person to be purified.

White Buffalo Calf Woman showed the people how to use the pipe. She filled it with ‘chan-shasha,’ red willow-bark tobacco.

She walked around the lodge four times after the manner of Anpetu-Wi, the great sun. This represents the circle without end, the sacred hoop, the road of life.

The woman placed a dry buffalo chip on the fire and lit the pipe with it. This was ‘peta-owihankeshni,’ the fire without end, the flame to be passed on from generation to generation.

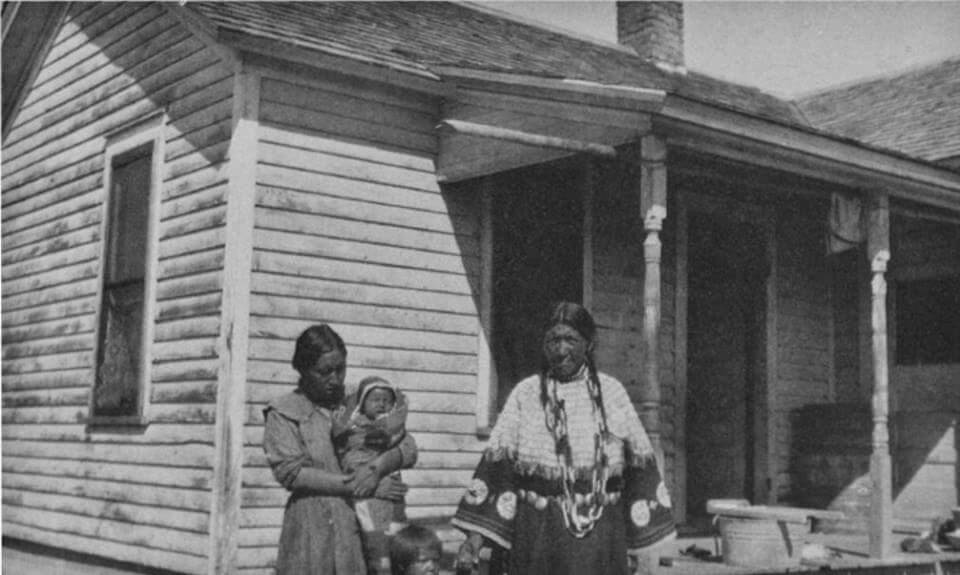

In the holy woman tradition the White Buffalo Woman brought the Pipe and showed the Lakota how to use it in a prayerful way. In this 1898 photo, Oglala Lakota Chief Red Cloud smokes the pipe on the South Dakota Rosebud Reservation. Photo by Jesse H. Bratley.

She told them that the smoke rising from the bowl was Tunkashila’s breath, the living breath of the great Grandfather Mystery.

The White Buffalo Calf Woman showed the people the right way to pray, the correct words and the gestures to use.

She taught them how to sing the pipe-filling song and how to lift the pipe up to the sky, toward Grandfather, and down toward Grandmother Earth, to Unci, and then to the four directions of the universe.

“With this holy pipe,” she said, “you will walk like a living prayer. With your feet resting upon the earth and the pipe stem reaching into the sky, your body forms a living bridge between the Sacred Beneath and the Sacred Above.

“Wakan Tanka smiles upon us, because now we are as one—earth, sky, all living things, the two-legged, the four-legged, the winged ones, the trees, the grasses. Together with the people, they are all related, one family. The pipe holds them all together.

“Look at this bowl,” said the White Buffalo Woman. “Its stone represents the buffalo, but also the flesh and blood of the red man. The buffalo represents the universe and the four directions, because he stands on four legs, for the four ages of creation.

“The buffalo was put in the west by Wakan Tanka at the making of the world, to hold back the waters. Every year he loses one hair, and in every one of the four ages he loses a leg.

“The sacred hoop will end when all the hair and legs of the great buffalo are gone, and the water comes back to cover the Earth. The wooden stem of this ‘chanunpa’ stands for all that grows on the earth.

“Twelve feathers hanging from where the stem—the backbone—joins the bowl—the skull—are from Wanblee Galeshka, the spotted eagle, the very sacred bird who is the Great Spirit’s messenger and the wisest of all flying ones. You are joined to all things of the universe, for they all cry out to Tunkashila.

“Look at the bowl: engraved in it are seven circles of various sizes. They stand for the seven sacred ceremonies you will practice with this pipe, and for the Oceti Sakowin, the seven sacred campfires of our Lakota nation.”

The White Buffalo Calf Woman then spoke to the women, telling them that it was the work of their hands and the fruit of their bodies which kept the people alive.

The White Buffalo Woman told Native American women “You are from Mother Earth. What you are doing is as great as what the warriors do.” In this 1923 photo Sicangu women with baby and young child show off their fine clothing on Rosebud Reservation.

“You are from the mother earth,” she told them. “What you are doing is as great as what the warriors do.”

And therefore the sacred pipe is also something that binds men and women together in a circle of love.

Man and woman with tepee. When a man takes a wife, they both hold the pipe at the same time and red trade cloth is wound around their hands, thus tying them together for life, said the White Buffalo woman. This photo is said to be of a Lakota wedding, possibly taken on the Rosebud reservation about 1912. Credit Tuell.

It is the one holy object in the making of which both men and women have a hand. The men carve the bowl and make the stem; the women decorate it with bands of colored porcupine quills.

When a man takes a wife, they both hold the pipe at the same time and red trade cloth is wound around their hands, thus tying them together for life.

The White Buffalo Woman had many things for her Lakota sisters in her sacred womb bag— corn, ‘wasna’ (pemmican), wild turnip. She taught them how to make the hearth fire.

She filled a buffalo paunch with cold water and dropped a red-hot stone into it. “This way you shall cook the corn and the meat,” she told them.

The White Buffalo Calf Woman also talked to the children, because they have an understanding beyond their years.

She told them that what their mothers and fathers did was for them, that their parents could remember being little once, and that they, the children, would grow up to have little ones of their own.

She told them: “You are the coming generation, that’s why you are the most important and precious ones. Some day you will hold this pipe and smoke it. Some day you will pray with it.”

She spoke once more to all the people: “The pipe is alive; it is a red being showing you a red life and a red road. And this is the first ceremony for which you will use the pipe. You will use it to keep the soul of a dead person, because through it you can talk to Wakan Tanka, the Great Mystery Spirit.

The Buffalo woman spoke to the people telling them that they were the purest among tribes and that is why they were chosen to be caretakers of the pipe for all people. This early photo shows a group of Sicangu Lakota men and women leaders from Rosebud Reservation.

“The day a human dies is always a sacred day. The day when the soul is released to the Great Spirit is another. Four women will become sacred on such a day. They will be the one to cut the sacred tree—the ‘can-wakan’—for the sun dance.”

She told the Lakota that they were the purest among the tribes, and for that reason Tunkashila had bestowed upon them the holy ‘chanunpa,’ They had been chosen to take care of it for all the Indian people on this turtle continent.

She spoke one last time to Standing Hollow Horn, the chief, saying, “Remember: this pipe is very sacred. Respect it and it will take you to the end of the road.

“The four ages of creation are in me; I am the four ages. I will come to see you in every generation. I shall come back to you.”

The sacred woman then took leave of the people, saying: “Toksha ake wancinyankin (wacinyanktin) ktelo—I shall see you again.”

The people saw her walking off in the same direction from which she had come, outlined against the red ball of the setting sun.

As she went, she stopped and rolled over four times. The first time, she turned into a black buffalo; the second into a brown one; the third into a red one. And finally, the fourth time she rolled over she turned into a white female buffalo.

The fourth time she rolled over, the White Buffalo Woman turned into a white buffalo and disappeared over the horizon. Credit White Cloud mounted in the National Buffalo Museum, Jamestown Sun.

A white buffalo is the most sacred living thing you could ever encounter. The White Buffalo Calf Woman disappeared over the horizon. Sometime she might come back.

Great herds of buffalo came to the Lakota in the White Buffalo woman tradition—and she brought many other gifts. Today Native Americans celebrate their modern tribal Buffalo herd on the Rosebud Indian Reservation—as on most other reservations in the Plains states. Credit Rosebud Tribe.

As soon as she had vanished, buffalo in great herds appeared, allowing themselves to be killed so that the people might survive.

And from that day on, our relatives, the buffalo, furnished the people with everything they needed—meat, skins for their clothes and tepee’s and bones for their many tools.

Other versions:

www.ilhawaii.net/~stonylore30

www.blackelkspeaks.unl.edu/appendix2

www.think-aboutit.com

NEXT: Buffalo Trucker for 24 Years

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog

Assisted Reproduction in Bison

Researcher Miranda Zwiefelhofer surveys herd of wood bison at one of the University of Saskatchewan’s Livestock and Forage Centre of Excellence’s facilities. Photo credit Eric Zwiefelhofer.

North American bison are made up of two distinct subspecies, the smaller plains bison and the larger wood bison. They are considered Near Threatened by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources.

Threats that impact the bison today include diseases in large free-roaming wild herds, hybridization between the bison subspecies and historical hybridization with cattle.

The wood bison are at an increased risk as all accessible wood bison herds in the world can be traced back to 11 founding bison. The remaining bison are locked away in the Greater Wood Buffalo National Park Region in Canada. The region is endemically infected with diseases such as Tuberculosis and Brucellosis making the herds inaccessible. Wood bison cannot be removed from these herds and assisted reproduction is a feasible method for accessing these valuable genetics in a bio-secure manner.

Bison Reproduction

Great strides have been taken in the past 15 years by academic institutions and zoological societies to better understand bison reproduction and create tools to assist in bison reproduction—otherwise known as assisted reproduction.

Female reproductive anatomy is primarily composed of two ovaries, two oviducts, a uterus with two uterine horns, a cervix and vagina. The ovaries have many fluid-filled follicles, each containing one oocyte which is the technical term for a mammalian egg.

Many people have heard of the bison “rut” each fall. From mid-July to September bison males bellow, wallow and fight for the top position in the herd. The victorious winner is rewarded with mating the females and the chance to share his genetics. This testosterone-driven phenomenon results in a synchronous calving event in the spring.

Plains bison bull at Custer State Park during the rut. Photo credit Miranda Zwiefelhofer.

One major difference between cattle and bison is that bison are seasonal breeders. Many people do not know that if female bison do not get pregnant in the short “rut” window, they can still get pregnant for several months, resulting in the odd calf born in late summer and fall.

Non-pregnant female bison will ovulate a follicle and release an oocyte for fertilization approximately every 20 days from August to February. This is called the ovulatory season. Unlike in cattle, bison stop ovulating from March to July in what is called the anovulatory season. Meanwhile, female cattle continually ovulate throughout the entire year.

The onset of reproductive seasonality in male (the rut) and female (ovulation of follicles) bison is triggered by the decreasing photoperiod (shorter day lengths) at the end of summer.

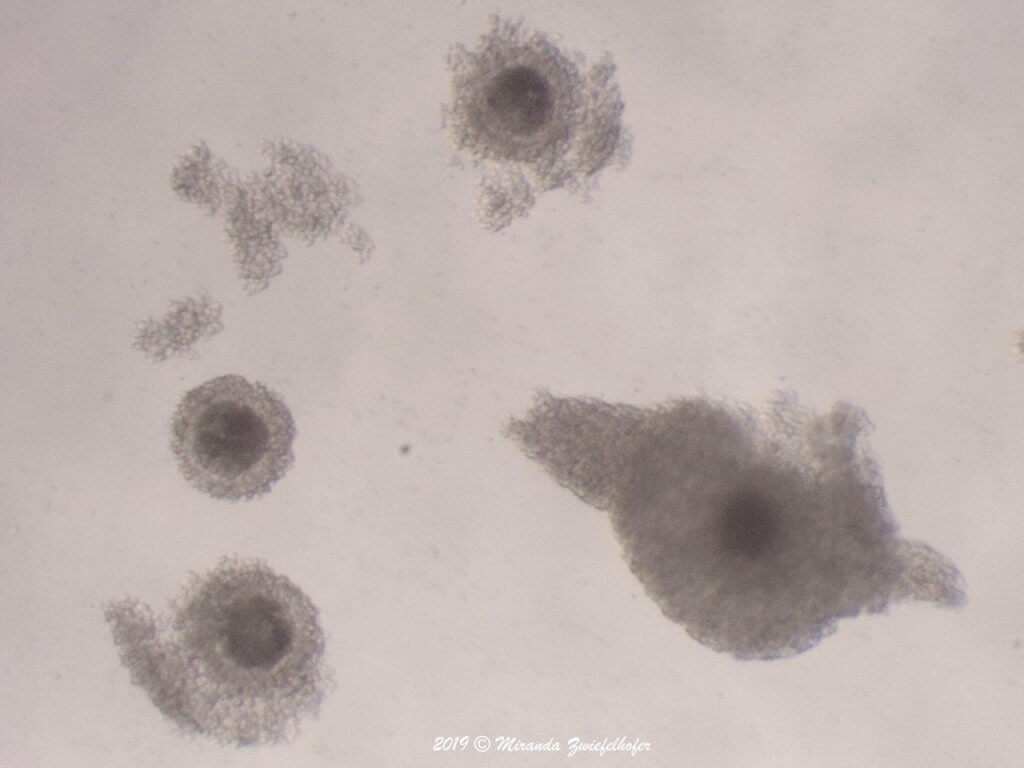

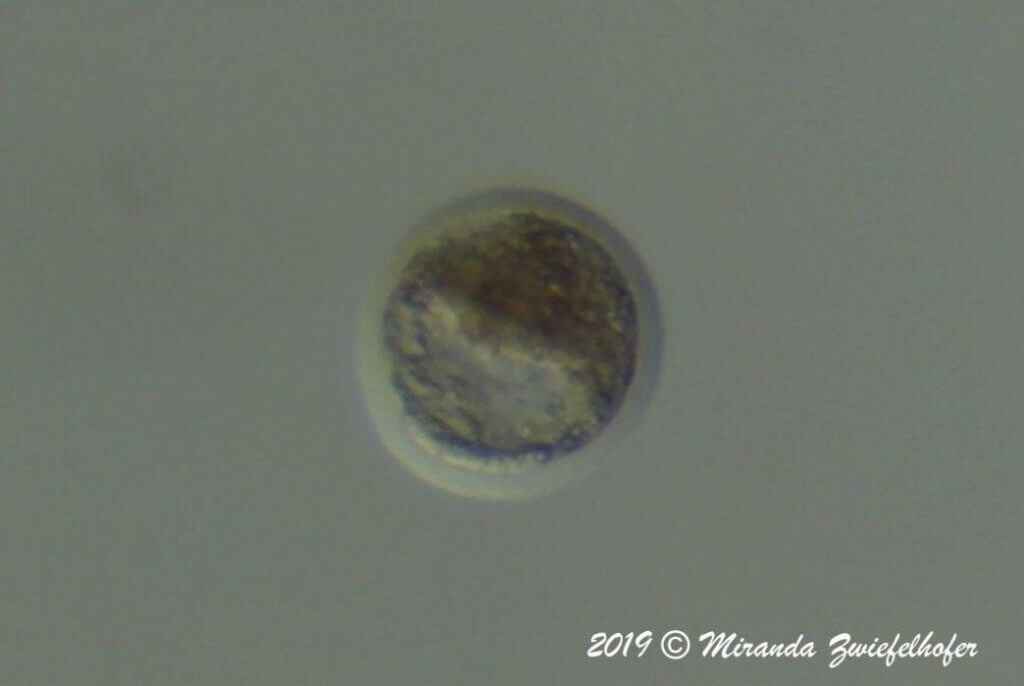

Each oocyte includes an inner ooplasm (the 1-cell egg), a tough outer protective casing called the zona pellucida and the hundreds of tiny granulosa cells which are attached to the outside of the zona pellucida and nurture the inner cell.

Bison oocytes (eggs). If the oocyte gets fertilized by a sperm, the cell will begin to divide and continue to migrate into the uterus. In about 265 days, happy and healthy bison calves are born. Credit MZ.

After the follicle ovulates, the oocyte is picked up by the hair-like fingers at the tip of the oviduct and is pushed further down the oviduct by contractions. The oocyte only has approximately 8 hours to be fertilized by a sperm. If a sperm does not find the oocyte, the oocyte will die and the female bison will ovulate another follicle in ~20 days.

If the oocyte does get fertilized by a sperm, the cell will begin to divide and continue to migrate into the uterus. The embryo will secrete a protein that maintains pregnancy. In approximately 265 days, the gestation length of the bison, happy and healthy bison calves are born.

Assisted Reproduction

The use of assisted reproductive techniques has become increasingly popular in humans, domestic species such as cattle, and for use in threatened and endangered species. The term assisted reproduction encompasses several techniques that simply unite bison germplasm (egg and sperm) which would not have a chance to meet because of geographical restrictions or other limiting factors.

Assisted reproductive techniques are tools that can help with infertility, commercial gain and conservation efforts. We emphasize that there is no genetic editing that occurs in any of the techniques described here.

Artificial Insemination (AI)

Eric Zwiefelhofer, PhD: A single semen sample can be loaded into a straw containing millions of sperm, then frozen and stored indefinitely in liquid nitrogen at -320.5° F until used. Credit MZ.

The use of ‘artificial’ can be somewhat misleading—when in fact all that is happening is the replacement of a live bull with a straw of semen, containing millions of sperm.

Semen can be collected from bison bulls in a chute system or even from a bull that is sedated. The semen is then brought to the laboratory where it is assessed for quality. This includes tests for concentration and movement of the sperm (motility) by microscopy.

A single semen collection from a bison bull can yield billions of sperm in a 5-10 mL sample. To freeze the semen, the semen sample is diluted using an extender which contains nutrients and cryoprotectants for the sperm to survive freezing. The semen sample can then be loaded into a straw containing millions of sperm and frozen.

The sample can then be stored indefinitely in liquid nitrogen (-320.5° F) until use. In 2015 the Toronto Zoo reported a bison calf born using artificial insemination from semen frozen for 35 years (https://www.torontozoo.com/press/!newsite-Releases.asp?pg=20150817). A single semen collection can yield hundreds of straws of semen to inseminate hundreds of cows.

The artificial insemination procedure is safe and quick (~1 minute) in bison. Female bison can either be inseminated after natural estrus occurs or after estrus is induced. Estrus is the natural behavior of a female for a short time where she is receptive to the male for breeding. This phenomenon occurs approximately 24 hours prior to ovulation described above.

The straw of semen is retrieved from the liquid nitrogen vessel and thawed in water at approximately 98°F for 1 minute. The straw is then loaded into a special pipette. The female is brought to the chute and a gloved hand is inserted into the rectum, while the pipette containing the semen straw is inserted into the vagina. The pipette is manipulated through the cervix using the gloved hand in the rectum. Once the uterus is reached, the semen (containing millions of sperm) is deposited and the sperm will begin the migration to the uterine horn and oviduct in search of an egg to fertilize.

In Vitro Fertilization

Simply stated, in vitro fertilization (more commonly referred to as IVF) combines an egg and a sperm in the laboratory. We can collect eggs from bison in a hydraulic chute, sedated bison on the ground and even from bison that have recently died.

The oocyte collection process is simple, quick, and pain free. It is very similar to oocyte collection in women, they even get an epidural so they do not feel a thing. With the use of ultrasonography, the ovaries are imaged and the follicles, which contain the oocytes, are aspirated (i.e. removed) using a vacuum pump. The follicular fluid is then filtered and the oocytes are recovered using a microscope. The oocytes are then washed and matured overnight.

Bison in vitro fertilization (IVF) combines an egg and a sperm in the laboratory. Credit MZ.

The following day, either fresh, cooled or frozen bison semen can be used to fertilize the matured oocytes. Unlike in artificial insemination, where one straw of semen can fertilize one female, in IVF a single straw of semen can fertilize hundreds of oocytes. This means that if you have rare and valuable semen, IVF allows these genetics to be passed on in many individuals rather than a single offspring. A small sperm sample is added to the media containing the oocytes.

The following day after fertilization the extra sperm and granulosa cells are removed and the fertilized oocytes (now referred to as embryos) are placed in clean media. We then culture them in an incubator for another 6 to 7 days.

During this time the embryo cells divide until it reaches around 32 cells where it begins to compact into one single cell mass. The cell mass then creates a small bubble inside it called a blastocoel. The blastocoel gets bigger and bigger until it actually hatches out of the zona pellucida (the outer casing).

For the purpose of conservation, it is best to freeze the embryo prior to hatching. Freezing the embryo allows us to keep the embryo in liquid nitrogen at -320.5° F. This allows us to keep the embryo indefinitely and transport the embryos in a bio-secure manner. Embryos are also able to be washed free of disease-causing agents such as bacteria and viruses.

IVF is an important tool for conservation. When there are only a few remaining animals in a herd or in a species, it is essential to make the most out of the situation. The northern white rhino is technically extinct with only two remaining females in existence. Embryos have been produced from collected oocytes and frozen semen preserved from a dead northern white rhino male through IVF. This breakthrough technology has also resulted in the birth of cheetah cubs which are considered a vulnerable species.

In vitro fertilization can also be used in domestic species when a small amount of semen is available from an old bull or when a bull dies unexpectedly. Two units of semen from a superior Wagyu bull (Mayura Itoshigenami Jnr) from Australia just recently sold for $140,000 AUD ($108,000 USD). These two units of semen could be used in IVF to fertilize hundreds of oocytes from multiple cows.

Embryo Transfer into Surrogate Bison Females

The incorporation of embryo transfer (ET) is a bio-secure approach to bring new genetics into a bison herd as it doesn’t require the movement of the animals themselves. Embryo transfer has been used since the 1970s in cattle with great success. The primary goal of ET in bison is for conservation purposes.

Wood bison IVF embryo produced at the University of Saskatchewan, SK, Canada. In embryo transfer it’s important to match the age of the embryo to the estrus cycle of the surrogate mother. But none of the calf’s genetics will come from the surrogate mother. Credit MZ.

An important aspect of ET is to match the age of the embryo to the time since estrus has occurred in the surrogate female. Naturally, ovulation and fertilization of an egg will occur approximately 1 day after estrus in a bison female. However, if there isn’t a male to naturally breed the female, the female will still ovulate, but no fertilization will occur. The infertile egg will continue to migrate into her uterine horn.

This is where we can incorporate the use of ET in female bison. Embryos produced in the lab will be approximately 7 to 8 days old (i.e., 7 to 8 days since fertilization has occurred). This means that in order to have success using ET, a surrogate female must be selected that was in estrus 8 to 9 days before as she will have an infertile egg in her uterus that is the same age as the embryo.

The in vitro-produced embryo can then be transferred non-surgically into the uterus. The body thinks that the embryo that was transferred is its own and nourishes it.

Probably the most interesting part about a calf produced through ET, is that none of its genetics will come from its surrogate mother. This means that you could produce an embryo from a pure plains bull and cow and transfer it into a pure wood bison surrogate—the resulting calf will be 100% plains genetics even though a wood bison carried it around for over 8 months in her uterus.

Wood and plains bison calves have been born from transferred frozen IVF embryos. Check out one of our more recent press releases from frozen IVF embryo bison calves born; https://news.usask.ca/articles/research/2020/usask-researchers-in-vitro-fertilization-successful-with-baby-bison.php. Future work focuses on improving these technologies to increase effectiveness.

2020 Wood bison calf from frozen IVF embryo at the University of Saskatchewan. Credit MZ.

Embryo transfer is a widely-accepted technology in the cattle industry. In 2019, more than 1.4 million embryos were produced in cattle according to the International Embryo Technology Society. The National Bison Association currently does not allow “in-vitro fertilization or other artificial reproduction practices for any purposes other than scientific research.”

However, these technologies are vital for conservation efforts. They can move genetics without transporting live bison which can be a huge biosecurity issue. With the assistance of wildlife veterinarians, bison can be sedated from a helicopter and semen or oocytes can be safely collected from them. Less than 30 minutes later, the sedation can be reversed and the bison is free to rejoin the herd.

The semen and eggs can then be sent back to the laboratory where eggs can be fertilized with sperm and produce embryos. Both the embryos and semen can be frozen for long-term usage and stored in vessels containing liquid nitrogen.

These frozen embryos and semen could then be shipped thousands of miles using FedEx or UPS (I’m not kidding—used extensively in the cattle industry) to other herds both domestically and internationally. Embryos/semen are transported in a dry shipper which holds liquid nitrogen vapor at a temperature of less than -238° F for upwards of two weeks. A single tank containing hundreds of units of semen and embryos could be shipped for less than $1000—I can’t imagine how much it would cost to ship hundreds of live bison over a thousand miles.

Eric Zwiefelhofer traveling with IVF wood bison embryos using a dry shipper. Credit MZ.

Imagine if the early bison conservationists had access to these reproductive technologies. Bison wouldn’t have to be rounded up off the prairies for days, placed in corrals, and forced onto rail cars to be transported for hundreds or thousands of miles. Semen and embryos could be produced from them and could be transported safely through FedEx or even as your checked-baggage on a flight.

The movement of genetics is a more economic option through the use of reproductive technologies. It also substantially decreases the transport stress of moving live bison resulting in fewer deaths.

Research is constantly evolving making assisted reproduction more effective and easier to accomplish. As seen in many endangered species, it is crucial to develop these technologies prior to them being needed. For the purpose of conservation in bison, collaborative efforts are in the works to implement these technologies to access rare genetics locked away in wild herds.

A commercial bison herd in Alberta Canada. Photo credit MZ.

We hope that these technologies will help the long-term health and resilience of plains and wood bison for future generations and that this article may ease some anxiety about the mystery which is assisted reproduction.

Miranda and Eric Zwiefelhofer

Author bio: Eric and Miranda Zwiefelhofer are a husband and wife team from Wisconsin and Minnesota. They attended the University of Wisconsin-River Falls for their undergraduate education where Miranda graduated with a degree in Biology and Secondary education and Eric in Dairy Science. They are currently living in Saskatoon, SK, Canada for their graduate studies in the Department of Veterinary Biomedical Sciences at the University of Saskatchewan which is a research-based program. They both specialize in reproductive physiology and advanced reproductive techniques. Eric specializes in oocyte collections, artificial insemination and embryo transfer while Miranda specializes in the in vitro production of embryos. Miranda is a PhD Candidate and will defend her thesis soon on Strategies for the use of reproductive technologies in bison. Eric obtained his PhD in January 2020 on Ovarian synchronization in cattle. He is currently working as a postdoctoral researcher for a second year with the University of Saskatchewan and the Toronto Zoo working on protocols to produce female offspring in bison. (Recent press release; https://news.usask.ca/articles/research/2021/wcvm-today-research-team-produces-first-female-bison-pregnancy-with-sex-sorted-sperm.php)

Author bio: Eric and Miranda Zwiefelhofer are a husband and wife team from Wisconsin and Minnesota. They attended the University of Wisconsin-River Falls for their undergraduate education where Miranda graduated with a degree in Biology and Secondary education and Eric in Dairy Science. They are currently living in Saskatoon, SK, Canada for their graduate studies in the Department of Veterinary Biomedical Sciences at the University of Saskatchewan which is a research-based program. They both specialize in reproductive physiology and advanced reproductive techniques. Eric specializes in oocyte collections, artificial insemination and embryo transfer while Miranda specializes in the in vitro production of embryos. Miranda is a PhD Candidate and will defend her thesis soon on Strategies for the use of reproductive technologies in bison. Eric obtained his PhD in January 2020 on Ovarian synchronization in cattle. He is currently working as a postdoctoral researcher for a second year with the University of Saskatchewan and the Toronto Zoo working on protocols to produce female offspring in bison. (Recent press release; https://news.usask.ca/articles/research/2021/wcvm-today-research-team-produces-first-female-bison-pregnancy-with-sex-sorted-sperm.php)

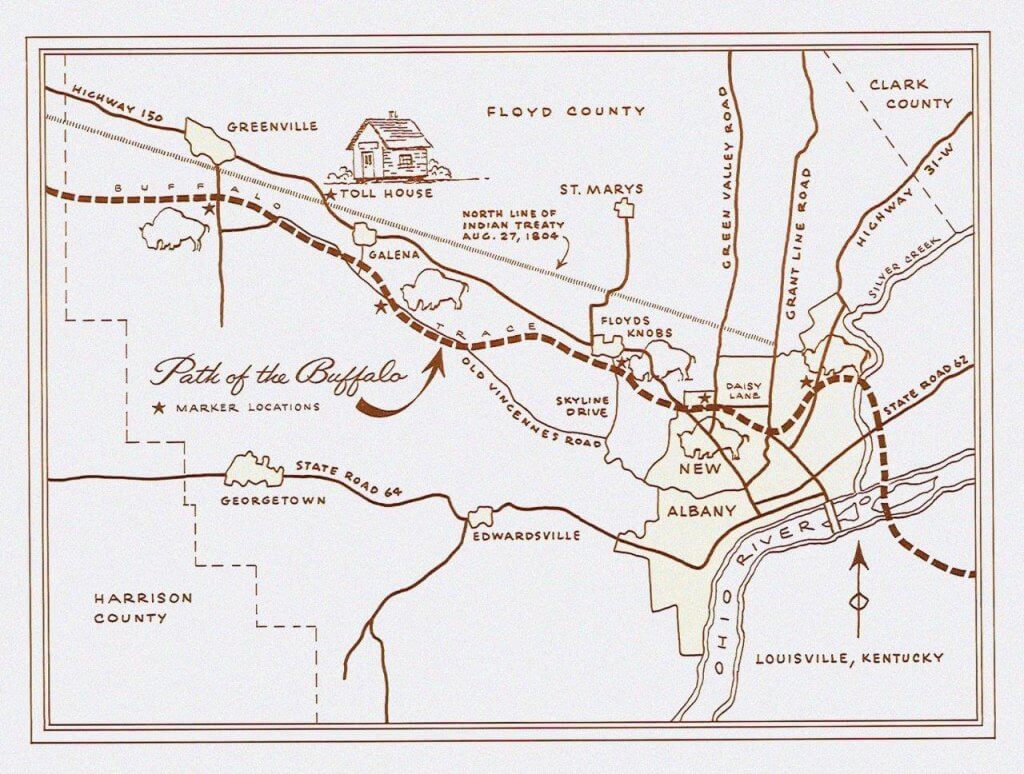

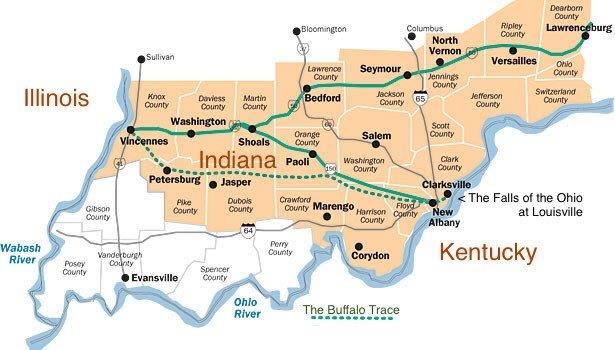

Buffalo Traces—’Path of the Buffalo,’ Part 2

Reenactment of the establishment of Initial Point on the bicentennial of the setting of this significant survey point. Deputy federal surveyors in period dress surveying the buffalo trace as in 1806. Ebenezer Buckingham Jr. U.S. Deputy Surveyor, established the original wooden post on September 1, 1805. The wooden post that marks the Initial Point was replaced by a corner stone in 1866. It was inscribed with an “S 31” for Section 31 by J.H. Lindley, Orange County Surveyor. This site is open to the public. Photo courtesy of the Initial Point Chapter of the Indiana Society of Professional Surveyors. US Forest Service.

Award Won

BEDFORD Oct 18, 2017—The Buffalo Trace Working Group with the Hoosier National Forest received the 2017 Indiana History Outstanding Event and Project Award from the Indiana Historical Society. The group was recognized as instrumental in uncovering the history of the Buffalo Trace and mapping its route through southern Indiana.

In December 2014 a group of interested Hoosiers—22 to 30 volunteers—met with the National Forest personnel and began searching for and documenting the remnants of Indiana’s oldest trail, known as the Vincennes Buffalo Trace through the National Forest and across the southern part of Indiana.

Within 3 years the group succeeded in mapping the original buffalo pathway, created a website devoted to the Buffalo Trace and an online interactive map highlighting historic resources along the route.

They were following the lead of early surveyors with William Rector and Crew in 1805 to 1807 —President Thomas Jefferson’s “army of young men”—who went through southern Indiana marking 160-acre farms with “north-south and east-west lines” with wood posts and dirt mounds every half mile.

Indiana was the first state to be completely laid out under the rectangular Public Land Survey System where the state was divided into six mile by six mile square townships, each containing 36 numbered sections of 640 acres each.

The buffalo left their mark in Indiana and Kentucky in deep, hard-packed roads—called Buffalo Traces.

David Ruckman, a retired surveyor and author who helped to locate the Trace, says it is the notes these young surveyors kept long ago that he and other modern surveyors relied on.

Their best resource became the notes and descriptions of those young surveyors.

They had marked the points where each quarter-section intersected the path of the buffalo—through the length and breadth of the Vincennes Buffalo Trace and the various routes that it took.

It was not a single route, but sometimes multiple trails—caused by local conditions such as years of flooding that may have changed routes.

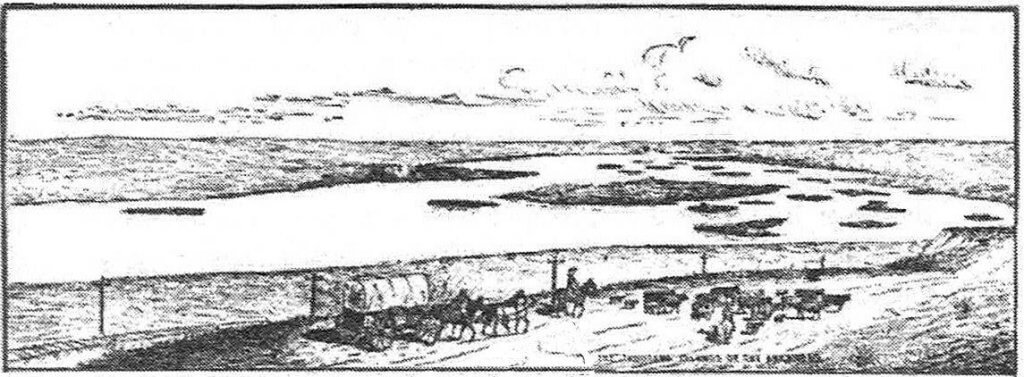

In places the Vincennes Buffalo Trace was 12 to 20 feet wide and worn down to a depth of 12 feet, even cutting down through solid rock.

These routes forged a hard-packed swath through hills, creeks and forests that were easily followed by Native Americans, early pioneers, soldiers during the Revolutionary War and later even automobiles. The pathways made travel easy through dense forests.

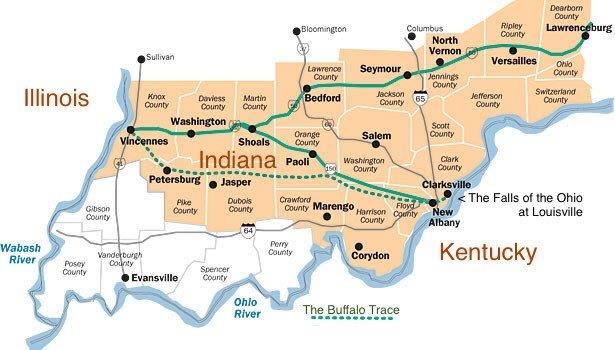

They helped to mark Hwy 150—the main route of ancient buffalo migrations between what are now Vincennes and Louisville. Huge herds of buffalo summered on the Illinois prairie and followed this trail to winter in Kentucky.

However, over the years most of these pathways were covered over and hidden by the new roads, corn fields and the urban sprawls of civilization.

Location of the Buffalo Trace cabin in the Smokey Mountains. The trace cut a broad swath through the dense trees in a wide, deep road traveled by Native Americans and many pioneers coming into Indiana as well as commercial traffic.

The working group—county surveyors, former surveyors, archeologists, research scientists, U.S. Forest Service workers and others—shared information they discovered about the Buffalo Trace, showing maps from the early 1800s with a road that followed the old bison trail across southern Indiana, with smaller trails that led to springs near where French Lick now stands and other salt licks into Kentucky.

Their mission was to research, locate and preserve the location and historical significance of the Buffalo Trace in southern Indiana and to present their information to schools and the public.

Within those 3 years they reached most of their goals:

- Use historical records to determine the location for the primary trail from the Ohio River crossing at Clarksville to the Wabash River in Vincennes.

- Physically locate the remaining remnants of the Trace in all the counties, which include Clark, Floyd, Harrision, Crawford, Orange, Dubois, Pike and Knox.

• Preserve the historical information and document its significance by publishing brochures and developing other resources that will educate the public about the Buffalo Trace.

• Produce a final document compiling all that the group has learned—in time to have it be part of Indiana’s bicentennial celebration in 2016. This included putting up signs, developing a website and planning special events, such as re-enacting early surveys.

Path of the Buffalo

According to David Ruckman buffalo were actually “The new kids on the block.” They arrived east of the Mississippi River about the time of European discovery of America in 1492, he writes, and had vanished from Indiana by 1810 –about 300 years in all.

By the year 1800, bison had mostly disappeared from east of the Mississippi River. Settlers were filling the lands known as the Northwest Territory—the area around the Great Lakes and farther south. Urban sprawl began covering most of their pathways.

Still, though it’s rare, the careful observer may find an ancient rut made by the buffalo.

Today, local historians and researchers are trying to piece together those ruts and knobs of the Buffalo Traces.

Reinactment: Indiana was the first state to be completely laid out under the rectangular Public Land Survey System where the State was divided into six mile by six mile square townships/ ranges containing 36 numbered sections of 640 acres each. Townships run north-south and ranges run east-west. Courtesy US Forest Service.

Today, US Route 150 between Vincennes and Louisville, Kentucky, follows a portion of this path. Sections of the improved Trace have been designated as part of a National Scenic Byway that crosses southern Indiana.

Historians have been alert too—surveying the ancient routes from historic documents, establishing parks along the way and placing signs at the salt licks.

Work in the Field

One part of the project that took hours was walking through fields and along creeks, looking for visible signs of the Buffalo Trace. Not easy, as it is covered nearly everywhere with layers of civilization.

David Drake, a retired surveyor from Orange County, shared the recent findings from some treks he took in Orange County with fellow surveyor Tom Moore. The two were using the 1805 survey by William Rector, who surveyed the Buffalo Trace to establish the Indian treaty lines through the state.

Rector followed the Trace, establishing on paper where it was located and then had to mark a line for the treaty that was at least a half mile north of the most northerly turn of the Trace.

Drake said he used old maps to locate parts of the Trace just south of French Lick, but other segments were missing. Some parts follow roads but end in fields and woods before picking up again on another road.

The area the group walked was one of the locations Drake believes may contain part of the Trace. The land is owned by Drake’s relative. In one area, the Rector map showed the Trace traveling up a hill.

“It went up a hill and we couldn’t figure out why,” he said.

After walking up the hill, Drake and Moore discovered the reason.

Depressions in the soil showed there was once a salt lick at the top—the attraction that led the buffalo up the hill. Then on the other side, the buffalo went down the hill and on their way.

Another time, Ruckman noted that an early trading post had been built at a certain point in the trail. For several years the activity there caused migrating buffalo herds to make a new trail veering around it.

Ruckman’s Retracement Notes

David Ruckman made extensive notes on his section of the Vincennes Trace—which began at the Ohio River crossing from Kentucky into Indiana.

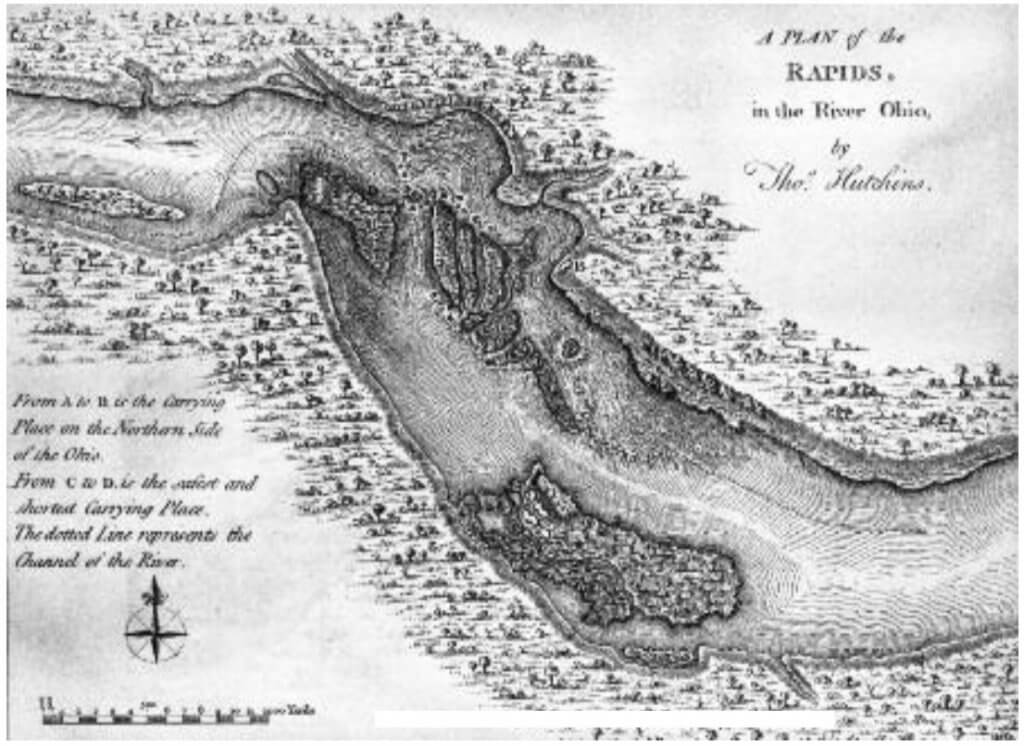

Ruckman began his survey at the Ohio River crossing in its shallowest point—as the buffalo had chosen for their crossing.

He said he had difficulty matching up his survey with the first notes of the early surveyors of 1805 to 1807 because “they did not start their Historic Survey at the Falls of the Ohio where our study starts, but northwest in Floyd County on the west line of the George Rogers Clark Military Grant on Greybrook Lane in New Albany.”

“[This] caused me many visits to the area looking for scars of the trace where I found none.”

Below is a sampling of his report:

- “The Trace mounts the north bank of the Ohio River at the intersection of Croghan and Vincennes Streets, (1107730.78 n, 294361.34 e ), in the original William Clark Survey Map of the 1000 acre town of Clarksville, being our true place of beginning;

A sketch of the rapids in the Ohio River. The Falls in the Ohio between what is now Louisville and Clarksville made a rapid descent over a series of ledges formed by Devonian rock rich in fossils. In high stages of water the falls disappeared completely. During low water times, the whole width of the river had the appearance of a series of waterfalls with great flats of rock beds. There is now a state park in the location where the buffalo and the historic trace crossed from Kentucky into Indiana. This site is open to the public. Sites listed as having limited access are private sites with specific areas or times that they are accessible to the public. Clark County. Falls of the Ohio State Park website.

- “Thence meandering north with the present day Emory Lane about one half mile to a Dry Trace Fork, whereupon the Dry Trace Fork went northwest, crossing Silver Creek at a point 90 feet north of the original McCullough Pike—Market Street Bridge location over Silver Creek, the other, northern Wet Weather Fork, continues north with said Emory Lane to cross State Road 62, ( Chief White Eye Trail).

- “Thence the Trace spread out across the flat Silver Creek Valley just west of Providence High School, as it continues north to intersect with the Gutford Road at the southeast high bank overlooking Silver Creek, fifty feet below.

- “Thence northeasterly and northwesterly following the present Gutford Road and said high bluff, passing Jane Sarles home and continuing about 5/8 mile to break northwest away from the present road, along the scar of the original Trace, ( 1116904.56 N, 292354.84 E ), to cross the slate bottom Silver Creek into Floyd C ounty at the Gutford crossing just east of Armstrong Bend;

- “Thence this northern fork mounted the west bank of Silver Creek, to join the present Old Ford Road meandering up the hill to the flat ridgetop known as Lone Star and the intersection with the Indiana Ancient Trail—Charlestown Road and the ongoing Ancient Trail out Klerner Lane through the Indiana University Southeast Campus to join Bald Knob Road and the ascent up the steep Floyd County Knobs;

- “Thence returning back to the Lone Star intersection, the Trace turned southwest following present day Charlestown Road about two miles to the intersection of the Trace where the Market Street Dry Fork Trace meets at Limerick Hill, the present intersection of Charlestown Road and the Vance Avenue;

- “Thence returning back to Silver Creek and the Market Street/ McCullough Pike crossing point 90 feet north of the now vanished bridge;

- “Thence, from there, it can be ascertained that the Trace made a fairly direct route nearly due west crossing the Ancient Trail “ Slate Run Trace”, through the east end of New Albany, passing Silver Street School, the National Cemetery and Hazelwood Jr. High,

- “Thence climbing 7 Vance Avenue continuing west crossing the Ancient Trail Charlestown Road at a high point of the old Limerick Hill ;

- “Thence continuing northwest along Vance Avenue to Falling Run;

- “Thence from Falling Run Valley the 1805 Trace jogs south to avoid Parkers Station at Daisy Lane;

Ruckman then discussed going uphill at the southwest “to join the Rector Survey beginning point on Greybrook Lane and Country Club Lane just south of the 1790 Parker Family Settlement at Daisy Lane and the Grant Line, the Parker Family being one of the very first settlements in Floyd County.“

Allowable error for the Rector Linear Survey was noted to be 1 survey chain per mile. Later Ruckman pointed out the surprising accuracy of that 1805 survey, considering this allowed error.

“Now forward West, based on Rector and other Surveyor notes.

- “Thence from the jog at Parkers Station at Greybrook and Country Club Drive hilltop the Rector notes of the 1805 Trace bend northwesterly following Greybrook Ridge past Elliott Phillips apartments and then descending down into the Falling Run Valley, where I once was a wild child swinging on grapevines and catching Falling Run catfish for dinner;

- “Thence across the Daisy Radio Tower tract to cross Daisy lane near Falling Run Creek and joining the Original Trace from Greybrook Hill;

- “Thence bending due west parallel to Daisy Lane to cross Green Valley Road just north of the intersection of Daisy Lane and Green Valley Road;

- “Thence bending northwest curving just south of Trinity Run and proceeding through the New Albany Water Park to cross State Street at I-265;

- “Thence meandering west through the Psi Duke substation and continuing along Trinity Run Valley (Binford road being on north edge), to exit said valley (1116508.54 N, 273038.37 E ) at the Holtz farm in the northwest quarter of Section 28 -2s-6e;

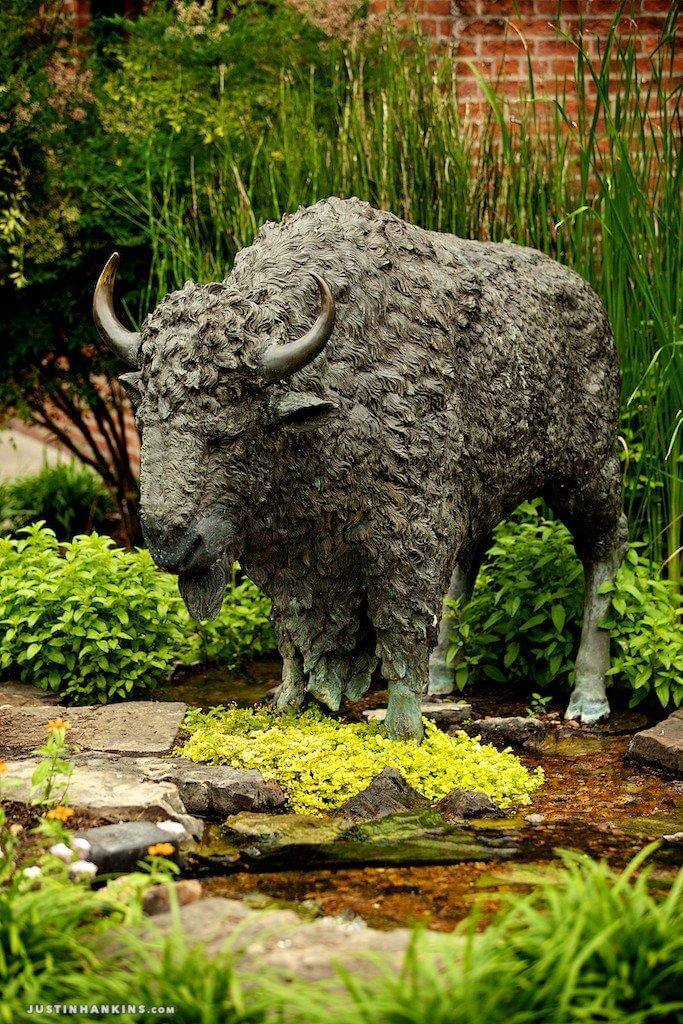

Buffalo sculptures are popular attractions in gardens and parks along the Buffalo Trace.

- “Thence turning northwest following the old Trace and stone mining road winding now up the east face of the Floyd County Knobs.

Ruckman wrote that the Trace at that point had been widened by stonemason wagons, mining and hauling stone downhill to the upstart New Albany Village, whose only stone was slate. He said this strip mine scar is over a mile in length and is sometimes mistaken for the Trace. “The Trace winds and wraps its way up the steep ridge bone knob spine from the Trinity Run Valley through the Holtz farm in Section 28, on its way to the top of the Knobs at Fawcett Fox Ridge, now Chambord.”

- “Thence [it goes] westerly, crossing Old Hill Road in Section 20 ( 1118875.25 N, 270921.35 E ), at the Hanka driveway proceeding along west, passing the William and Edith Hanka 1800’s hand hewn log lodge home in the southeast quarter of Section 20, 2s, – 6e; continuing west just north of the old Copler home along the ridge top through the tall oak timber. The Trace is barely visible in the woods, bending just south of a stone at the center of section 20, to follow a flat top wooded ridgetop and descending the west side of the Floyds Knobs through Charles Roberson’s land down a well-trod fork on the left (1119161.03 N, 267869.44 E and an existing incline pathway on the right (1119657.49 N, 268075.82 E), before coming together in the Floyds Knobs Valley;

- “Thence west crossing said valley and Little Indian Creek (1119748.48 N, 267683.89 E) at the existing road creek crossing, (about 1, 000 feet south of Paoli Pike at Schupert’s corner);

- “Thence westerly up the western side of the Floyds Knobs Valley and grassy field, passing just south of the Jim Bezy machine shop and a Doe Creek Tributary intersecting said Indian Creek,

- “Thence westerly up the hill across Knable Court, meandering west just south of Luther Road, crossing Lawrence Banet Road at Luther Road;

- “Thence continuing west, crossing a small tributary at Ken and Sandy Groh’s driveway and the center of Section 19;

- “Thence meandering west with the Ken Groh driveway ( 1120461.31 N, 263204.64 E ), departing same west up the gentle grass hillside, passing just north of the Dennis Richard’s home and then the Monte Givens home before crossing US 150, about 700 feet south of Luther Road;

- “Thence northwest through the Sperzel Woods to join Luther Road at the Highlander Ridge high point in Section 24 – 2s,- 5e;

- “Thence flowing west along Luther Road, diverting from the existing road at the Yeager farm entrance;

- “Thence westerly through the Ray Yeager farm and following the Rector calls in a direct line through the lands of Richard Libs and passing the Dr. Ragan home place, about 528 feet west of the common corners of Sections 13,14,23 and 24. Both Rector and the Rectangular Surveyors agree that the Trace crossed approximately 528 feet west of the northeast corner of Section 23, t-2-s, r-5-e, on the border between Mt. Saint Francis and Dr. Ragan’s home place;

- “Thence proceeding west and northwest, passing just north of Floyd Central High School in Section 14 2s, 5e, proceeding northwest through the south portions of Benchmark and Quailwood, crossing northwest into Section 15 and through the Ruckman/ McWilliams Farm Plat in Sections 15 and 10, in a direct course about 5,412 feet, to a turn near the NW corner of the SW ¼ of the SE ¼ of Section 10- t-2-s, r-5-e , just southwest of Galena, and being one of the most northeasterly turns of the Trace, whereupon Rector’s return treaty line was to be at least ½ mile north of this turn.

Ruckman briefly hints at the excitement and discouragement that drove him on, day by day.

“In my retracement, I had many exciting ‘discovery’ moments. . . sometimes standing and or walking where the Buffalo trod.

“However, there were many disappointing days wandering and searching for any possible faint Trace scars, nearly invisible now. Or following an old abandoned former roadway only to find it turn away from the overall westerly Trace direction, proving it was not evidence of the Trace, merely a now-abandoned farm road.”

cc

Parks along the Trace

Historians have been active too—surveying the ancient routes from historic documents, establishing parks along the way and placing signage to identify Buffalo Licks and other historic points.

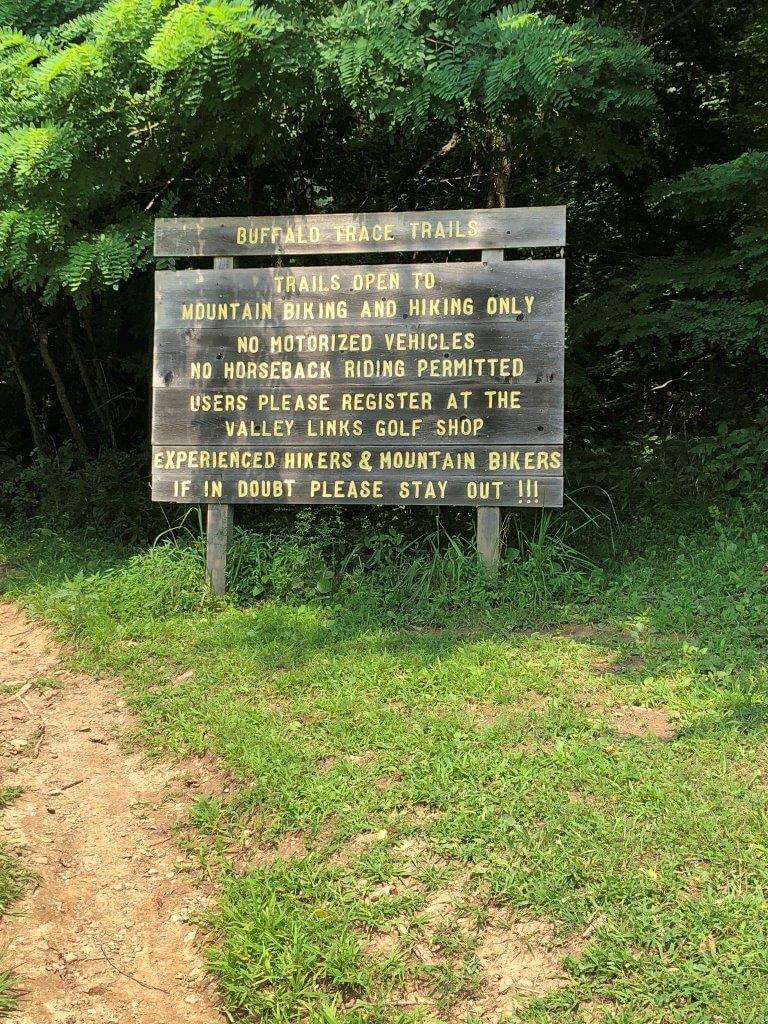

Historic and modern signs mark the Buffalo Traces. Parts of the Original Trace have been protected for years and marked with hand-painted signs as the above which warns “Experienced Hikers & Mountain bikers—if in doubt please stay out!!!” Presumably this warning is an after thought to spare the fragile trail from wear and tear of experts who have been here before.

Parts of the Original Trace have been protected, including sections in the Hoosier National Forest and a small tract within Buffalo Trace Park, a preserve maintained by Harrison County, Indiana—and with these recent revelations—perhaps there’ll be more signage to come.

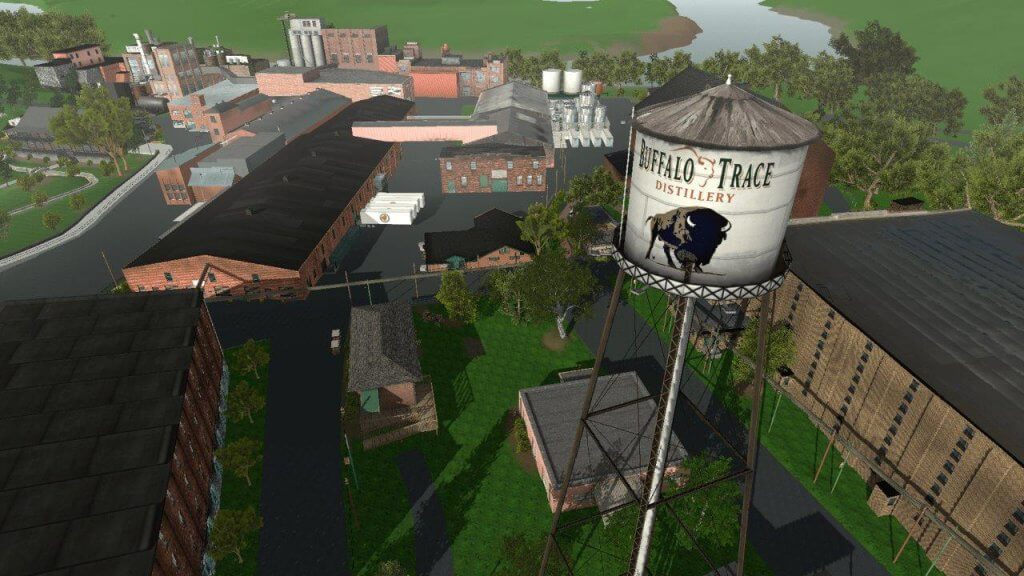

Distilleries along the trace attempt to usurp the Buffalo Trace Designation for their own purposes—and make it appear that the Trace and even buffalo themselves are overshadowed by Buffalo Trace Bourbon. Note the spectacular water tower! Try googling Buffalo Trace and see how many liquor bottles pop up! But despite this emphasis from some quarters, we have George Bird Grinnell’s nineteenth century statement of fact that “Americans are water-drinking people!” He contrasts this with drinking habits of people in many other places in the world—and therefore, he points out that we Americans need to keep our water clean.

Are historic roads important? Many major transportation routes of prehistoric and early historic times have been lost to history. Some are completely forgotten, both their story and their location lost.

For others, remnants of the road exist but their history is lost, and for some their physical location is lost, still the background of the road lingers in local folklore and histories

However, growing interest in prehistoric and historic trails has led to an increase in archaeological and historical research of these cultural resources, as remnants of old roads and trails abound. As here in Indiana they can be recognized as areas of over grown ruts, wide paths free of trees in forested areas and pathways eroded into the landscape.

Some can be found with a dry laid stonewall or single course of stone along the side of the road. Most of these can be attributed to small lanes used to get around the property by the landowner, or for farming or logging.

Survey notes, plat maps and other documents provide clues as archeologists continue to discover more sections, aided by modern technologies such as GIS and GNSS. Today some are part of the newly designated Historic Pathways and National Scenic Byway.

Buffalo Trace website: https://buffalotrace.indianashistoricpathways.org/

Story Map: https://usfs.maps.arcgis.com/apps/MapTour/index.html?appid=3d76729e954f4b63ba73cd5956e8039f

Hoosier National Forest: https://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/hoosier/specialplaces/?cid=fsbdev3_017492

——

NEXT

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog

Buffalo Traces—‘Path of the Buffalo’, Part 1

US Hwy 150 follows the Vincenne Buffalo Trace across southern Indiana from the falls of the Ohio River on the east. Historic pathways.org.

Bison east of the Mississippi have mostly disappeared from American memory. Yet, up until the Revolutionary War, buffalo could be found from New York to Florida and from the Mississippi River to the tide-water lands of the east coast.

They left their mark in Indiana and Kentucky in deep, hard-packed trails—called Buffalo Traces.

Various trails also converged around the major salt licks, probably near present-day Lick Fork and French Lick in Indiana.

Buffalo only arrived east of the Mississippi River about the time of European discovery of America in 1492, according to Indiana historian David Ruckman, a retired surveyor and author who is helping to locate the Trace. They vanished from Indiana by 1810 –“along with most of Indiana’s Native American families and the remnants of their proud tribes.”

The mineral springs of the valley, now famous for their high sulfur content, also contained high natural levels of salt.