Reenactment of the establishment of Initial Point on the bicentennial of the setting of this significant survey point. Deputy federal surveyors in period dress surveying the buffalo trace as in 1806. Ebenezer Buckingham Jr. U.S. Deputy Surveyor, established the original wooden post on September 1, 1805. The wooden post that marks the Initial Point was replaced by a corner stone in 1866. It was inscribed with an “S 31” for Section 31 by J.H. Lindley, Orange County Surveyor. This site is open to the public. Photo courtesy of the Initial Point Chapter of the Indiana Society of Professional Surveyors. US Forest Service.

Award Won

BEDFORD Oct 18, 2017—The Buffalo Trace Working Group with the Hoosier National Forest received the 2017 Indiana History Outstanding Event and Project Award from the Indiana Historical Society. The group was recognized as instrumental in uncovering the history of the Buffalo Trace and mapping its route through southern Indiana.

In December 2014 a group of interested Hoosiers—22 to 30 volunteers—met with the National Forest personnel and began searching for and documenting the remnants of Indiana’s oldest trail, known as the Vincennes Buffalo Trace through the National Forest and across the southern part of Indiana.

Within 3 years the group succeeded in mapping the original buffalo pathway, created a website devoted to the Buffalo Trace and an online interactive map highlighting historic resources along the route.

They were following the lead of early surveyors with William Rector and Crew in 1805 to 1807 —President Thomas Jefferson’s “army of young men”—who went through southern Indiana marking 160-acre farms with “north-south and east-west lines” with wood posts and dirt mounds every half mile.

Indiana was the first state to be completely laid out under the rectangular Public Land Survey System where the state was divided into six mile by six mile square townships, each containing 36 numbered sections of 640 acres each.

The buffalo left their mark in Indiana and Kentucky in deep, hard-packed roads—called Buffalo Traces.

David Ruckman, a retired surveyor and author who helped to locate the Trace, says it is the notes these young surveyors kept long ago that he and other modern surveyors relied on.

Their best resource became the notes and descriptions of those young surveyors.

They had marked the points where each quarter-section intersected the path of the buffalo—through the length and breadth of the Vincennes Buffalo Trace and the various routes that it took.

It was not a single route, but sometimes multiple trails—caused by local conditions such as years of flooding that may have changed routes.

In places the Vincennes Buffalo Trace was 12 to 20 feet wide and worn down to a depth of 12 feet, even cutting down through solid rock.

These routes forged a hard-packed swath through hills, creeks and forests that were easily followed by Native Americans, early pioneers, soldiers during the Revolutionary War and later even automobiles. The pathways made travel easy through dense forests.

They helped to mark Hwy 150—the main route of ancient buffalo migrations between what are now Vincennes and Louisville. Huge herds of buffalo summered on the Illinois prairie and followed this trail to winter in Kentucky.

However, over the years most of these pathways were covered over and hidden by the new roads, corn fields and the urban sprawls of civilization.

Location of the Buffalo Trace cabin in the Smokey Mountains. The trace cut a broad swath through the dense trees in a wide, deep road traveled by Native Americans and many pioneers coming into Indiana as well as commercial traffic.

The working group—county surveyors, former surveyors, archeologists, research scientists, U.S. Forest Service workers and others—shared information they discovered about the Buffalo Trace, showing maps from the early 1800s with a road that followed the old bison trail across southern Indiana, with smaller trails that led to springs near where French Lick now stands and other salt licks into Kentucky.

Their mission was to research, locate and preserve the location and historical significance of the Buffalo Trace in southern Indiana and to present their information to schools and the public.

Within those 3 years they reached most of their goals:

- Use historical records to determine the location for the primary trail from the Ohio River crossing at Clarksville to the Wabash River in Vincennes.

- Physically locate the remaining remnants of the Trace in all the counties, which include Clark, Floyd, Harrision, Crawford, Orange, Dubois, Pike and Knox.

• Preserve the historical information and document its significance by publishing brochures and developing other resources that will educate the public about the Buffalo Trace.

• Produce a final document compiling all that the group has learned—in time to have it be part of Indiana’s bicentennial celebration in 2016. This included putting up signs, developing a website and planning special events, such as re-enacting early surveys.

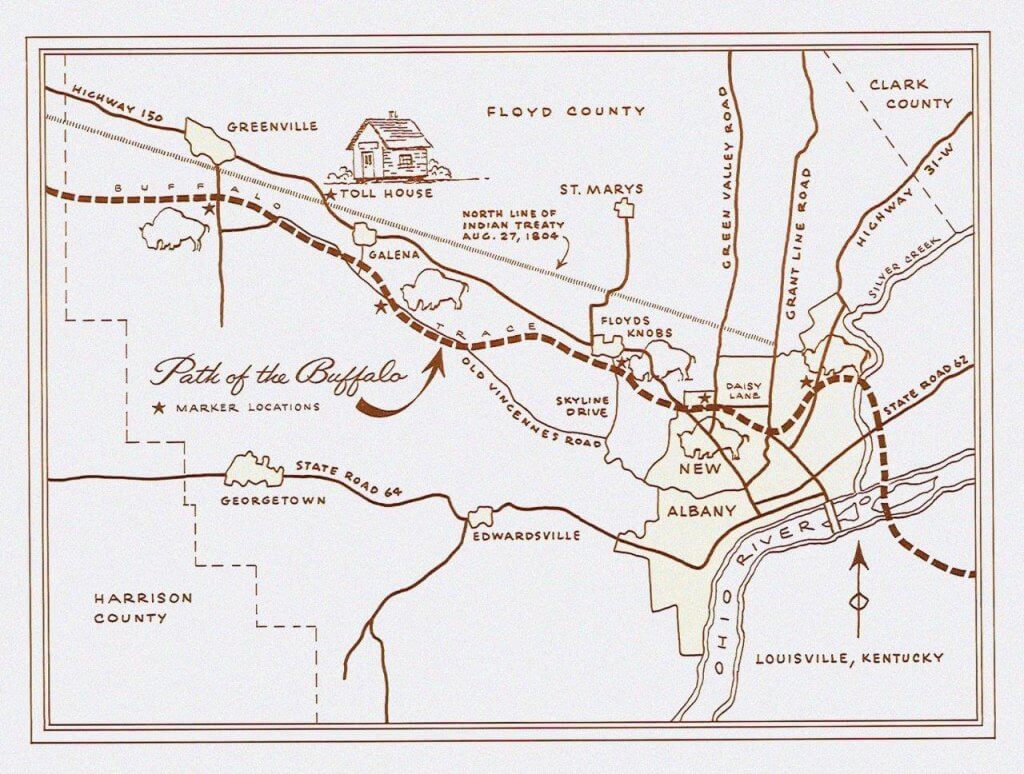

Path of the Buffalo

According to David Ruckman buffalo were actually “The new kids on the block.” They arrived east of the Mississippi River about the time of European discovery of America in 1492, he writes, and had vanished from Indiana by 1810 –about 300 years in all.

By the year 1800, bison had mostly disappeared from east of the Mississippi River. Settlers were filling the lands known as the Northwest Territory—the area around the Great Lakes and farther south. Urban sprawl began covering most of their pathways.

Still, though it’s rare, the careful observer may find an ancient rut made by the buffalo.

Today, local historians and researchers are trying to piece together those ruts and knobs of the Buffalo Traces.

Reinactment: Indiana was the first state to be completely laid out under the rectangular Public Land Survey System where the State was divided into six mile by six mile square townships/ ranges containing 36 numbered sections of 640 acres each. Townships run north-south and ranges run east-west. Courtesy US Forest Service.

Today, US Route 150 between Vincennes and Louisville, Kentucky, follows a portion of this path. Sections of the improved Trace have been designated as part of a National Scenic Byway that crosses southern Indiana.

Historians have been alert too—surveying the ancient routes from historic documents, establishing parks along the way and placing signs at the salt licks.

Work in the Field

One part of the project that took hours was walking through fields and along creeks, looking for visible signs of the Buffalo Trace. Not easy, as it is covered nearly everywhere with layers of civilization.

David Drake, a retired surveyor from Orange County, shared the recent findings from some treks he took in Orange County with fellow surveyor Tom Moore. The two were using the 1805 survey by William Rector, who surveyed the Buffalo Trace to establish the Indian treaty lines through the state.

Rector followed the Trace, establishing on paper where it was located and then had to mark a line for the treaty that was at least a half mile north of the most northerly turn of the Trace.

Drake said he used old maps to locate parts of the Trace just south of French Lick, but other segments were missing. Some parts follow roads but end in fields and woods before picking up again on another road.

The area the group walked was one of the locations Drake believes may contain part of the Trace. The land is owned by Drake’s relative. In one area, the Rector map showed the Trace traveling up a hill.

“It went up a hill and we couldn’t figure out why,” he said.

After walking up the hill, Drake and Moore discovered the reason.

Depressions in the soil showed there was once a salt lick at the top—the attraction that led the buffalo up the hill. Then on the other side, the buffalo went down the hill and on their way.

Another time, Ruckman noted that an early trading post had been built at a certain point in the trail. For several years the activity there caused migrating buffalo herds to make a new trail veering around it.

Ruckman’s Retracement Notes

David Ruckman made extensive notes on his section of the Vincennes Trace—which began at the Ohio River crossing from Kentucky into Indiana.

Ruckman began his survey at the Ohio River crossing in its shallowest point—as the buffalo had chosen for their crossing.

He said he had difficulty matching up his survey with the first notes of the early surveyors of 1805 to 1807 because “they did not start their Historic Survey at the Falls of the Ohio where our study starts, but northwest in Floyd County on the west line of the George Rogers Clark Military Grant on Greybrook Lane in New Albany.”

“[This] caused me many visits to the area looking for scars of the trace where I found none.”

Below is a sampling of his report:

- “The Trace mounts the north bank of the Ohio River at the intersection of Croghan and Vincennes Streets, (1107730.78 n, 294361.34 e ), in the original William Clark Survey Map of the 1000 acre town of Clarksville, being our true place of beginning;

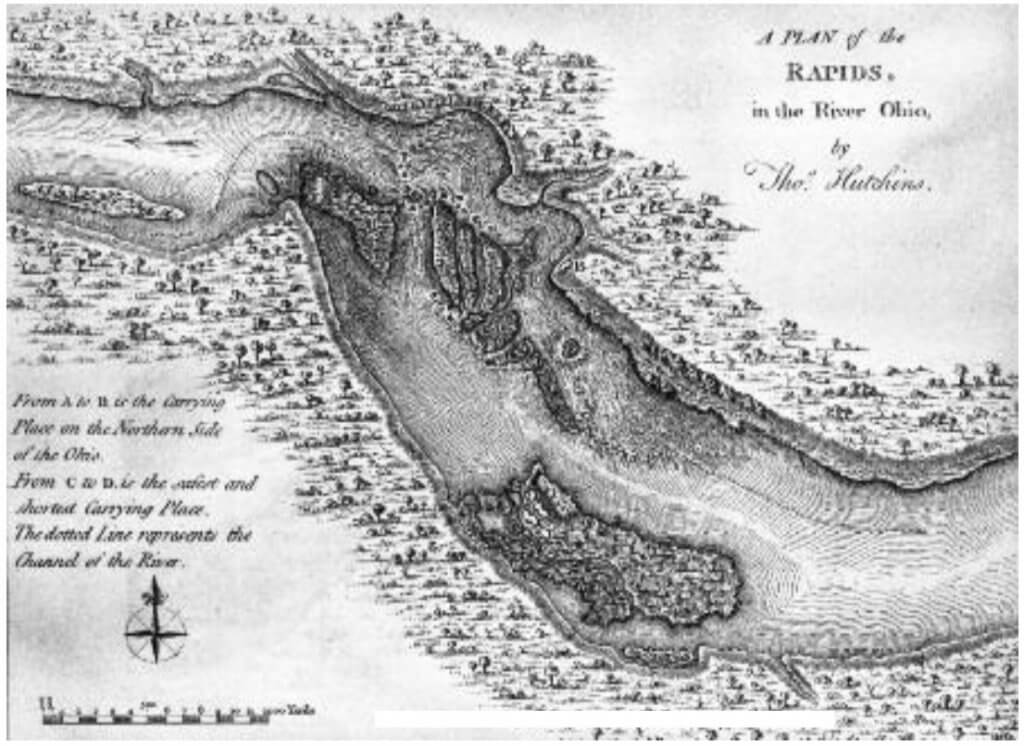

A sketch of the rapids in the Ohio River. The Falls in the Ohio between what is now Louisville and Clarksville made a rapid descent over a series of ledges formed by Devonian rock rich in fossils. In high stages of water the falls disappeared completely. During low water times, the whole width of the river had the appearance of a series of waterfalls with great flats of rock beds. There is now a state park in the location where the buffalo and the historic trace crossed from Kentucky into Indiana. This site is open to the public. Sites listed as having limited access are private sites with specific areas or times that they are accessible to the public. Clark County. Falls of the Ohio State Park website.

- “Thence meandering north with the present day Emory Lane about one half mile to a Dry Trace Fork, whereupon the Dry Trace Fork went northwest, crossing Silver Creek at a point 90 feet north of the original McCullough Pike—Market Street Bridge location over Silver Creek, the other, northern Wet Weather Fork, continues north with said Emory Lane to cross State Road 62, ( Chief White Eye Trail).

- “Thence the Trace spread out across the flat Silver Creek Valley just west of Providence High School, as it continues north to intersect with the Gutford Road at the southeast high bank overlooking Silver Creek, fifty feet below.

- “Thence northeasterly and northwesterly following the present Gutford Road and said high bluff, passing Jane Sarles home and continuing about 5/8 mile to break northwest away from the present road, along the scar of the original Trace, ( 1116904.56 N, 292354.84 E ), to cross the slate bottom Silver Creek into Floyd C ounty at the Gutford crossing just east of Armstrong Bend;

- “Thence this northern fork mounted the west bank of Silver Creek, to join the present Old Ford Road meandering up the hill to the flat ridgetop known as Lone Star and the intersection with the Indiana Ancient Trail—Charlestown Road and the ongoing Ancient Trail out Klerner Lane through the Indiana University Southeast Campus to join Bald Knob Road and the ascent up the steep Floyd County Knobs;

- “Thence returning back to the Lone Star intersection, the Trace turned southwest following present day Charlestown Road about two miles to the intersection of the Trace where the Market Street Dry Fork Trace meets at Limerick Hill, the present intersection of Charlestown Road and the Vance Avenue;

- “Thence returning back to Silver Creek and the Market Street/ McCullough Pike crossing point 90 feet north of the now vanished bridge;

- “Thence, from there, it can be ascertained that the Trace made a fairly direct route nearly due west crossing the Ancient Trail “ Slate Run Trace”, through the east end of New Albany, passing Silver Street School, the National Cemetery and Hazelwood Jr. High,

- “Thence climbing 7 Vance Avenue continuing west crossing the Ancient Trail Charlestown Road at a high point of the old Limerick Hill ;

- “Thence continuing northwest along Vance Avenue to Falling Run;

- “Thence from Falling Run Valley the 1805 Trace jogs south to avoid Parkers Station at Daisy Lane;

Ruckman then discussed going uphill at the southwest “to join the Rector Survey beginning point on Greybrook Lane and Country Club Lane just south of the 1790 Parker Family Settlement at Daisy Lane and the Grant Line, the Parker Family being one of the very first settlements in Floyd County.“

Allowable error for the Rector Linear Survey was noted to be 1 survey chain per mile. Later Ruckman pointed out the surprising accuracy of that 1805 survey, considering this allowed error.

“Now forward West, based on Rector and other Surveyor notes.

- “Thence from the jog at Parkers Station at Greybrook and Country Club Drive hilltop the Rector notes of the 1805 Trace bend northwesterly following Greybrook Ridge past Elliott Phillips apartments and then descending down into the Falling Run Valley, where I once was a wild child swinging on grapevines and catching Falling Run catfish for dinner;

- “Thence across the Daisy Radio Tower tract to cross Daisy lane near Falling Run Creek and joining the Original Trace from Greybrook Hill;

- “Thence bending due west parallel to Daisy Lane to cross Green Valley Road just north of the intersection of Daisy Lane and Green Valley Road;

- “Thence bending northwest curving just south of Trinity Run and proceeding through the New Albany Water Park to cross State Street at I-265;

- “Thence meandering west through the Psi Duke substation and continuing along Trinity Run Valley (Binford road being on north edge), to exit said valley (1116508.54 N, 273038.37 E ) at the Holtz farm in the northwest quarter of Section 28 -2s-6e;

Buffalo sculptures are popular attractions in gardens and parks along the Buffalo Trace.

- “Thence turning northwest following the old Trace and stone mining road winding now up the east face of the Floyd County Knobs.

Ruckman wrote that the Trace at that point had been widened by stonemason wagons, mining and hauling stone downhill to the upstart New Albany Village, whose only stone was slate. He said this strip mine scar is over a mile in length and is sometimes mistaken for the Trace. “The Trace winds and wraps its way up the steep ridge bone knob spine from the Trinity Run Valley through the Holtz farm in Section 28, on its way to the top of the Knobs at Fawcett Fox Ridge, now Chambord.”

- “Thence [it goes] westerly, crossing Old Hill Road in Section 20 ( 1118875.25 N, 270921.35 E ), at the Hanka driveway proceeding along west, passing the William and Edith Hanka 1800’s hand hewn log lodge home in the southeast quarter of Section 20, 2s, – 6e; continuing west just north of the old Copler home along the ridge top through the tall oak timber. The Trace is barely visible in the woods, bending just south of a stone at the center of section 20, to follow a flat top wooded ridgetop and descending the west side of the Floyds Knobs through Charles Roberson’s land down a well-trod fork on the left (1119161.03 N, 267869.44 E and an existing incline pathway on the right (1119657.49 N, 268075.82 E), before coming together in the Floyds Knobs Valley;

- “Thence west crossing said valley and Little Indian Creek (1119748.48 N, 267683.89 E) at the existing road creek crossing, (about 1, 000 feet south of Paoli Pike at Schupert’s corner);

- “Thence westerly up the western side of the Floyds Knobs Valley and grassy field, passing just south of the Jim Bezy machine shop and a Doe Creek Tributary intersecting said Indian Creek,

- “Thence westerly up the hill across Knable Court, meandering west just south of Luther Road, crossing Lawrence Banet Road at Luther Road;

- “Thence continuing west, crossing a small tributary at Ken and Sandy Groh’s driveway and the center of Section 19;

- “Thence meandering west with the Ken Groh driveway ( 1120461.31 N, 263204.64 E ), departing same west up the gentle grass hillside, passing just north of the Dennis Richard’s home and then the Monte Givens home before crossing US 150, about 700 feet south of Luther Road;

- “Thence northwest through the Sperzel Woods to join Luther Road at the Highlander Ridge high point in Section 24 – 2s,- 5e;

- “Thence flowing west along Luther Road, diverting from the existing road at the Yeager farm entrance;

- “Thence westerly through the Ray Yeager farm and following the Rector calls in a direct line through the lands of Richard Libs and passing the Dr. Ragan home place, about 528 feet west of the common corners of Sections 13,14,23 and 24. Both Rector and the Rectangular Surveyors agree that the Trace crossed approximately 528 feet west of the northeast corner of Section 23, t-2-s, r-5-e, on the border between Mt. Saint Francis and Dr. Ragan’s home place;

- “Thence proceeding west and northwest, passing just north of Floyd Central High School in Section 14 2s, 5e, proceeding northwest through the south portions of Benchmark and Quailwood, crossing northwest into Section 15 and through the Ruckman/ McWilliams Farm Plat in Sections 15 and 10, in a direct course about 5,412 feet, to a turn near the NW corner of the SW ¼ of the SE ¼ of Section 10- t-2-s, r-5-e , just southwest of Galena, and being one of the most northeasterly turns of the Trace, whereupon Rector’s return treaty line was to be at least ½ mile north of this turn.

Ruckman briefly hints at the excitement and discouragement that drove him on, day by day.

“In my retracement, I had many exciting ‘discovery’ moments. . . sometimes standing and or walking where the Buffalo trod.

“However, there were many disappointing days wandering and searching for any possible faint Trace scars, nearly invisible now. Or following an old abandoned former roadway only to find it turn away from the overall westerly Trace direction, proving it was not evidence of the Trace, merely a now-abandoned farm road.”

cc

Parks along the Trace

Historians have been active too—surveying the ancient routes from historic documents, establishing parks along the way and placing signage to identify Buffalo Licks and other historic points.

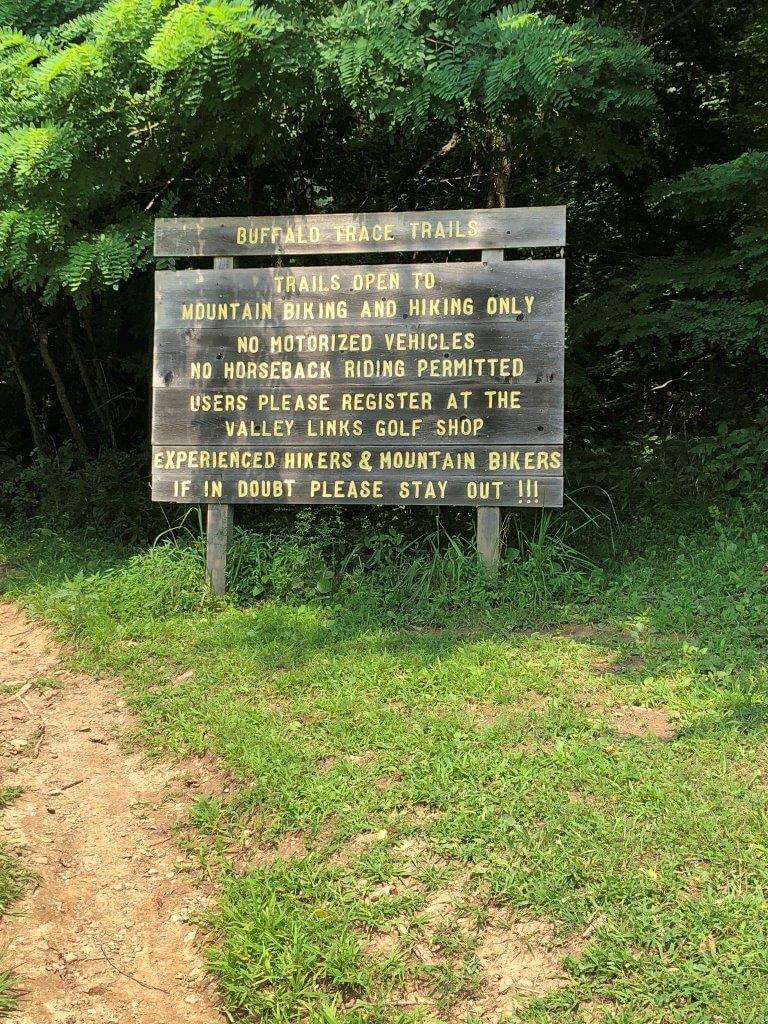

Historic and modern signs mark the Buffalo Traces. Parts of the Original Trace have been protected for years and marked with hand-painted signs as the above which warns “Experienced Hikers & Mountain bikers—if in doubt please stay out!!!” Presumably this warning is an after thought to spare the fragile trail from wear and tear of experts who have been here before.

Parts of the Original Trace have been protected, including sections in the Hoosier National Forest and a small tract within Buffalo Trace Park, a preserve maintained by Harrison County, Indiana—and with these recent revelations—perhaps there’ll be more signage to come.

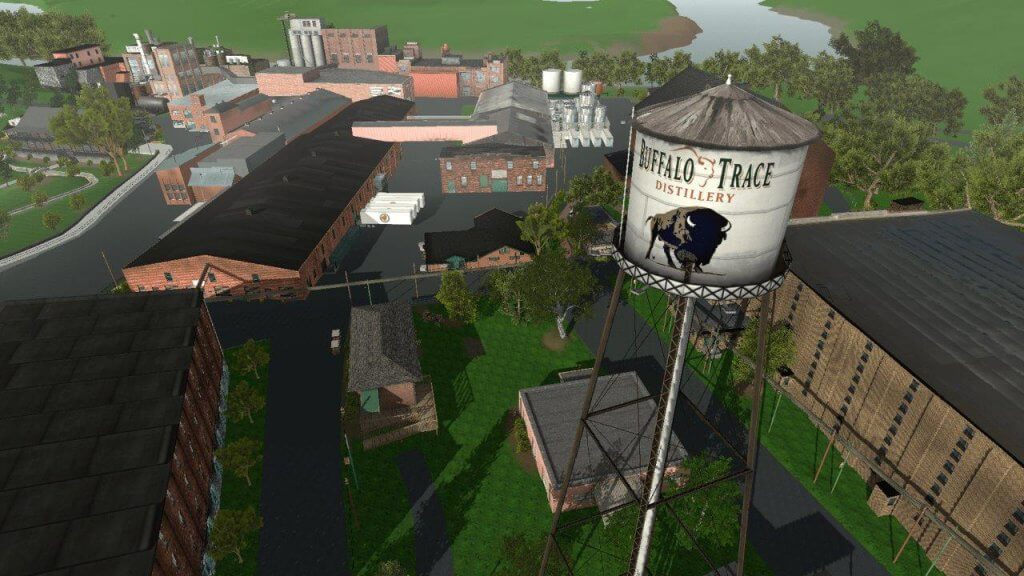

Distilleries along the trace attempt to usurp the Buffalo Trace Designation for their own purposes—and make it appear that the Trace and even buffalo themselves are overshadowed by Buffalo Trace Bourbon. Note the spectacular water tower! Try googling Buffalo Trace and see how many liquor bottles pop up! But despite this emphasis from some quarters, we have George Bird Grinnell’s nineteenth century statement of fact that “Americans are water-drinking people!” He contrasts this with drinking habits of people in many other places in the world—and therefore, he points out that we Americans need to keep our water clean.

Are historic roads important? Many major transportation routes of prehistoric and early historic times have been lost to history. Some are completely forgotten, both their story and their location lost.

For others, remnants of the road exist but their history is lost, and for some their physical location is lost, still the background of the road lingers in local folklore and histories

However, growing interest in prehistoric and historic trails has led to an increase in archaeological and historical research of these cultural resources, as remnants of old roads and trails abound. As here in Indiana they can be recognized as areas of over grown ruts, wide paths free of trees in forested areas and pathways eroded into the landscape.

Some can be found with a dry laid stonewall or single course of stone along the side of the road. Most of these can be attributed to small lanes used to get around the property by the landowner, or for farming or logging.

Survey notes, plat maps and other documents provide clues as archeologists continue to discover more sections, aided by modern technologies such as GIS and GNSS. Today some are part of the newly designated Historic Pathways and National Scenic Byway.

Buffalo Trace website: https://buffalotrace.indianashistoricpathways.org/

Story Map: https://usfs.maps.arcgis.com/apps/MapTour/index.html?appid=3d76729e954f4b63ba73cd5956e8039f

Hoosier National Forest: https://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/hoosier/specialplaces/?cid=fsbdev3_017492

——

NEXT

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog