Photographer nearly trampled to death

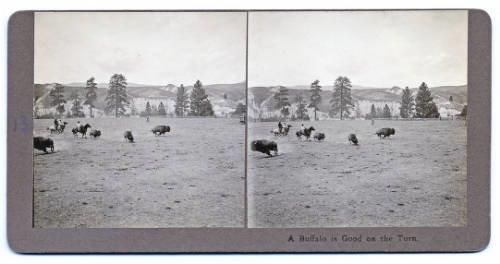

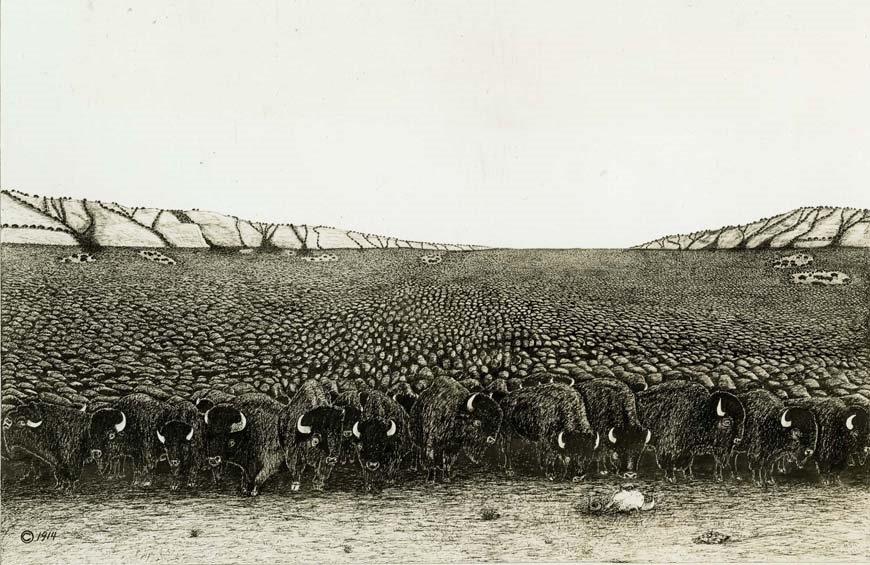

View of cowboys on horses chasing bison out of the pine trees, with white cliffs across the Flathead River in the background. Forsyth used dual cameras to shoot these stereographic scenes. Montana Historical Society.

After college he moved west, still selling for Underwood and Underwood, an early producer and distributor of stereographic views. Attracted by the scenic beauty of Yellowstone Park, Forsyth worked as a tour guide and stage driver in Yellowstone five summers, taking scenic stereographic views along the way, and then set up a photography studio in Butte where he sold them.

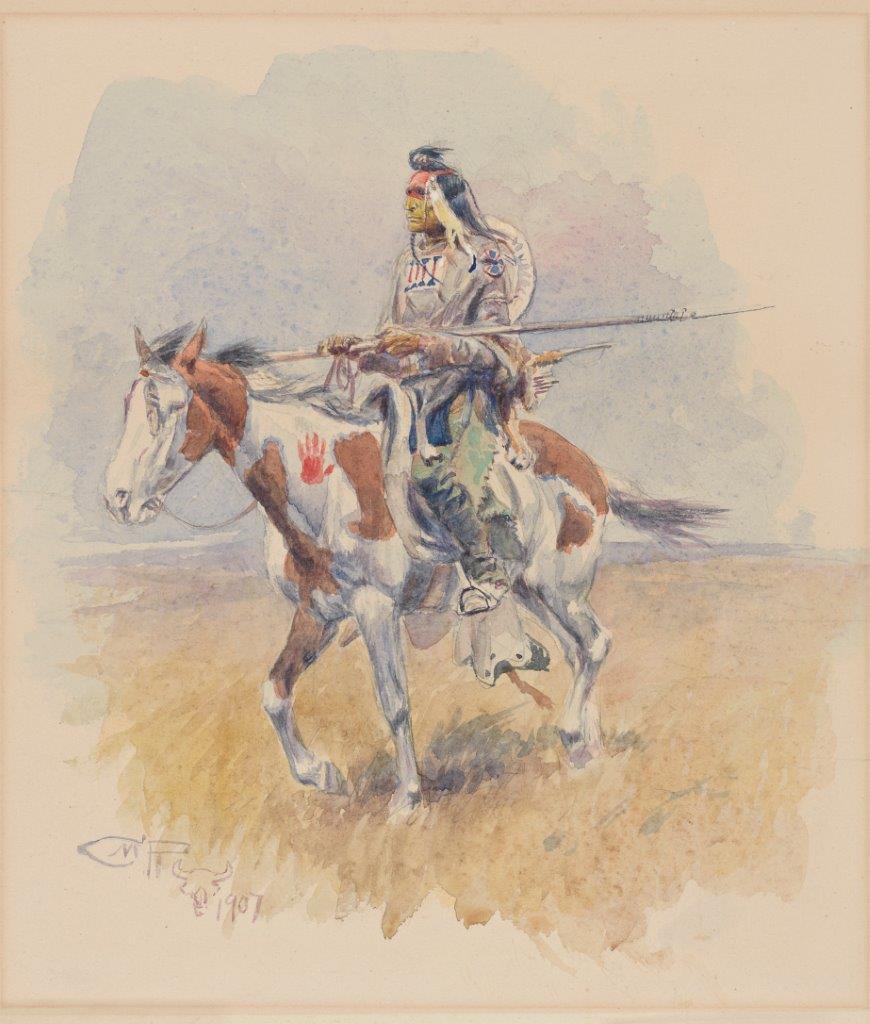

Fascinated by what he read of Michel Pablo’s great roundup of near-wild bison he took his cameras to Ronan, MT. There he made friends with Charlie Russell, a cowboy painter also attracted to the dramatic buffalo action they saw every day.

Forsyth shot stereographic views and Russell painted and sketched numerous scenes over the first three summers during which the Pablo buffalo roundup shipped most of the animals to Canada.

One day Forsyth scrambled down into some trees to get the perfect shot as the cowboy wranglers brought in a herd of buffalo across the river toward the corrals.

The Wainwright, Alberta, newspaper reported Forsyth’s near brush with death as the buffalo herd leaped up out of the river and charged directly toward him.

“The entry of the buffalo into the corral came nearly being accompanied by a regrettable fatality.

“Mr. Forsyth, an enterprising photographer from Butte, Montana, being anxious to get some photos of the animals in the water, had stationed himself at a point of vantage amidst a clump of trees close to one of the booms in the river where he judged he would be out of path of the oncoming herd.

“However they chose to take the bank directly below where he was standing, and before he could reach safety they were upon him in a mad, irresistible stampede.

“How he escaped being trampled to instant death is a miracle which even he cannot realize.

“He has a recollection of the herd rushing upon him and of having in some way clutched a passing calf which he clung to until it passed under a tree.

“He then managed to grasp a branch and although he was unable to pull himself up out of danger he was able to keep above the feet of the plunging herd.

“His dangling legs were bruised and cut by their horns and his clothes torn to shreds, but he still clung to the limb for life.

“Twice the herd passed under him as they circled back in an attempt to escape, but fortunately before he became exhausted they rushed into the corral.

“The Canadian Pacific officials and riders who knew the location chosen by Forsyth shuddered when they saw the animals rush in there and expected to find his body trampled out of semblance in the clay.

“Consequently, they rejoiced to find the luckless photographer slightly disfigured, but still hugging his friend the tree in his disheveled wardrobe.”

As the buffalo stampeded up out of the trees and into the corral, the cowboys rode to his rescue.

Scratched, bleeding and with his clothing ripped apart, Forsyth dropped out of the tree.

On the ground were his two costly cameras that shot dual picture stereographs, both shattered into many pieces and trampled in the mud.

He greeted his would-be rescuers with a sheepish grin, saying, “I think I have had enough of buffalo!”

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog