Teachers: Do you remember what you did last summer?

Summers are busy for all of us—and all too short with lots to do. As a teacher you may be trying to crowd in all the trips and events you missed the last 2 years.

One thing we can absolutely guarantee, if you come to southwest North Dakota for the BSC Dakota Bison Tour it will be a field trip you’ll never forget!

We’re sending out a special appeal to you who are teachers—because this entire BSC Bison Symposium is planned especially for you. It brings you the ammunition you need to tell the full Dakota buffalo story—at its most fascinating. And for good measure, it brings you right into the middle of a large buffalo herd.

This is a 3-day Buffalo Event that will enrich Teachers:

Bismarck State College’s Dakota Bison Symposium, June 23-25

Register now: call 701-224-5600 or visit

https://bismarckstate.edu/events/Dakota-Bison-Symposium/

An opportunity to learn about our National Mammal, the American Bison—past, present and future—through presentations, panel discussions, film, art, tours, exhibits, Native America music and dancing culinary arts, and a tour of authentic buffalo historic sites.

- It’s a day you’ll never forget

- You’ll never look at buffalo the same again

- When you teach Buffalo and early Native American life in our state you’ll have tremendous stories to tell—and the resources to do it well.

We Made a Trial Run

One beautiful morning last summer Loren Luckow and I met Larry Skogen and Erik Holland—leaders of our BSC Bison Symposium planning committee from Bismarck—at the historic Kokomo in Lemmon SD.

Inside the Kokomo are John Lopez’s fighting full size bison bulls made from spare parts. And other sculped gems.

We’ll grab a quick take before heading out on buses to briefly circle the Petrified Park. Then on to Shadehill Buffalo Jump.

Larry Skogen is a hometown educator who spent his career as President of Bismarck State College in Bismarck. Then he retired and suddenly had plenty of enthusiasm and time (we remind him!) to help plan this Symposium.

Erik Holland is an educator too. In fact, Curator of Education at the North Dakota State Historical Society. The system in our state is that the Historical Society does North Dakota curriculum material for schools, and teachers can use what they want, as they think best for their own classes. Especially for 4th and 8th grades, and on to advanced classes in High School and College.

Together we took a day-long trial run—the 4 of us—just to see how long it would take at each stop and how feasible the whole Dakota Bison Symposium tour would be with maybe 2 or 3 buses filled with visitors.

Of course I wanted to show our visitors everything we have here!

But I’ve had some experience with my own family—kids and grandkids.

They all love to go out and see some of our Buffalo sites! But “some” is relative. They get tired of hiking over the hills—especially if it’s hot, or cold or really windy.

And when we stop for a picnic, they’re usually done. They pretty much want to stay in one place for awhile—or go home.

This is truly a unique place where we live—and especially the buffalo heritage. My husband Bert, a veterinarian thought so too. He enjoyed working buffalo herds.

But whenever I’d say “Wouldn’t it be fun to have a few buffalo? We have such a nice pasture right here at the edge of town. People would love to see them.”

He’d just shake his head; “Too hard on fences.” Then he’d quickly change the subject. He didn’t even want to talk about it.

In introducing you to our southwest region of North Dakota, I would love to show you many, many things. How about this:

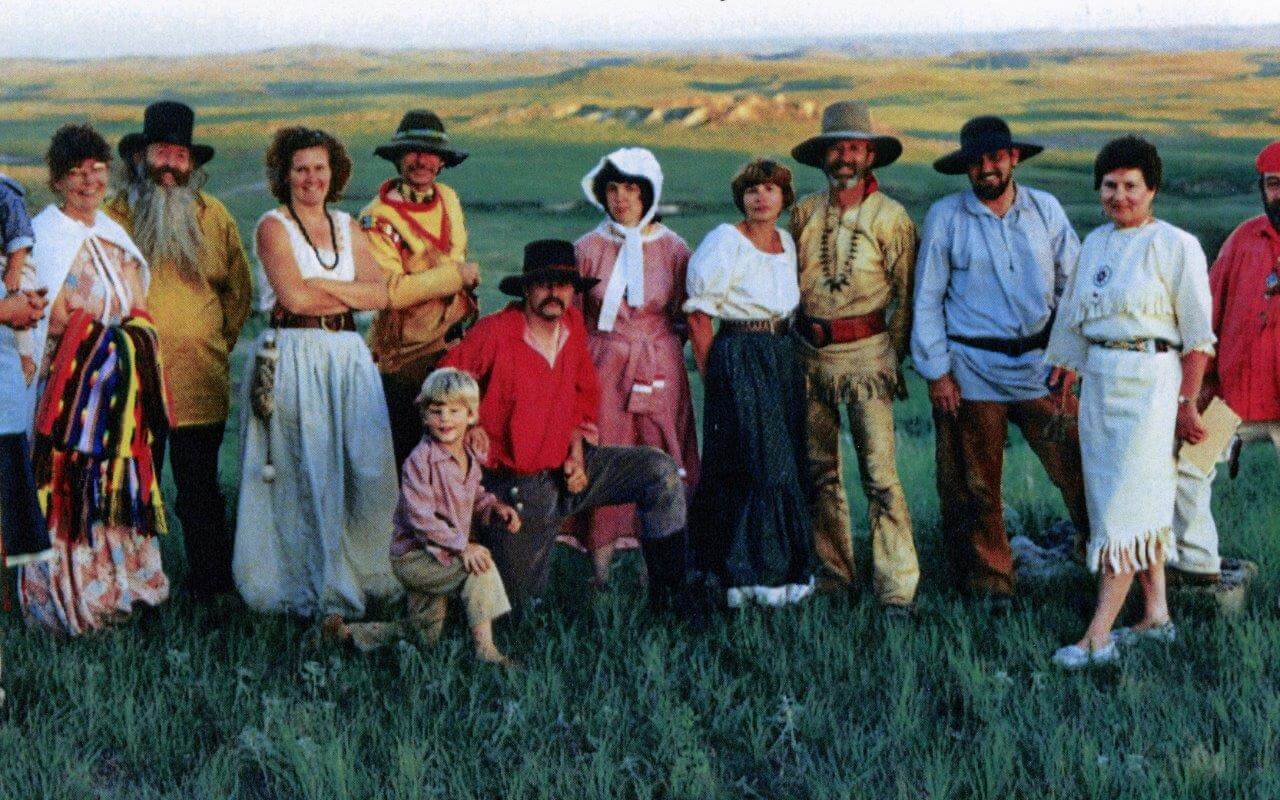

The US Forest Service pasture in this photo shows buttes and badlands of the North Grand River in what we call Sitting Bull’s Last Stand. He and his hunting band from near Mobridge came and in two days—October 12 and 13, 1883—killed the very last great wild herd. About 1,200 buffalo in all.

In his 1899 book “The Extermination of the American Bison,” William Hornaday wrote, “There was not a hoof left. That wound up the buffalo in the Far West. Only a stray bull being seen here and there afterwards.” In this photo you see a special group of visiting Buckskinners. We’ve led many tours here. It’s also been called the Butchering Site because the early settlers found so many bison skulls and bones here.

A beautiful, higher-altitude outcropping of rocky hills, the pine-covered Slim Buttes are a delightful place for hiking, camping and picnicking.

One of the last great hunts was here too. A hunting party of about 100—mostly the Lakota Dupree family, their relatives and friends came here near Christmas in 1880, hunted buffalo for 3 months in an extremely cold and snowy winter, as described by the missionary Thomas Riggs, invited along.

They killed some 2,000 buffalo and took home over 500 prime hides.

The Battle of Slim Buttes was launched when survivors from the Battle of the Little Big Horn under Chief American Horse camped here overnight on their way back to the Black Hills and were attacked by remnants of General Crook’s branch of the US army on Sept 9 and 10, 1876.

This horseshoe bend in the South Grand River is where we think the Native American Dupree family might have come over the horizon (at center left in this photo) in their horse-drawn buckboard with a few outriders to rescue calves that next spring after their winter hunt—in 1881 or 1882.

They became internationally famous for being one of the 5 family groups who saved the buffalo. Imagine them finding a herd of buffalo grazing here—drinking and resting among the big old cottonwood trees. Photo by FM Berg.

The last of the great wild buffalo herds came here around Christmas 1880 to the relative safety of what was then the Great Sioux Indian Reservation. They were in flight from white hide hunters armed with big guns who cut across the corner of Montana coming north and east in pursuit.

Instead of crossing the Yellowstone River, this half—about 50,000 in all—came east into the Great Sioux Reservation. The other half crossed the Yellowstone, then fled north into the waiting guns of hoards of white and Native hunters and were soon slaughtered. For nearly 3 years these last buffalo survived—longer than anywhere else. Native elders said they came to care for their Lakota brothers and sisters before the white hunters killed them all.

The Blacktail Trail in US Forest Service Pasture 9 offers a small lake stocked with bass, with fishing dock, picnic area and most dramatic of all—a 7-mile walking loop through rugged badlands, gumbo buttes and fascinating rock and gumbo formations. Photo FM Berg.

At the trailhead hikers hold open a spring-loaded gate designed to close itself—preventing cattle from invading the picnic site. FMB.

The Blacktail Trail offers a nice place to consider the complex relationship between the buffalo and Native people who lived here—from being a source of food to a font of social and cultural inspiration and connection to spiritual life. Native Americans honor the buffalo as sacred in ceremonies, stories, artwork, song and dance. FMB.

Blacktail Trail winds through rugged badlands and buttes to a hilltop blooming with wild flowers juniper trees and sagebrush. Many traditional Native stories of this land speak to the mystery of the origin of life. A common belief held by many Plains tribes is of the creation of humans and buffalo emerging from a cave or hole in the ground. FMB.

Here’s our agenda for the Friday, June 24 Field Trip:

7:15 am Check-in, Bus Assignments

7:45 am Buses Depart BSC

When you ride the bus you’ll hear buffalo tales and lore told by our local bus hosts: Ceil Anne Clement, Val Braun (both former teachers) and John Joyce, MD (retired doc and self-taught historian).

We hope also to have some Native Americans telling cultural buffalo traditions and stories along the way. Photo by Ronda Fink.

9:00 am Kokomo Sculpture Gallery, Lemmon, SD (single-day visitors meet buses here)

Inside the Kokomo Inn are John Lopez’s world-famous sculptures designed from spare parts. We’ll take a look at the buffalo and other treasures before heading out to briefly circle the Petrified Park in the buses. Then on to Shadehill Buffalo Jump. Photo credit John Lopez.

Shadehill Buffalo Jump

One of our first stops is to view the authentic buffalo jump at Shadehill from across the lake on the north side.

It’s been authenticated as an ancient jump by three separate archaeological teams including the University of North Dakota at Grand Forks. Photo by Vince Gunn.

11:45 am Lunch, Shadehill Recreation Area

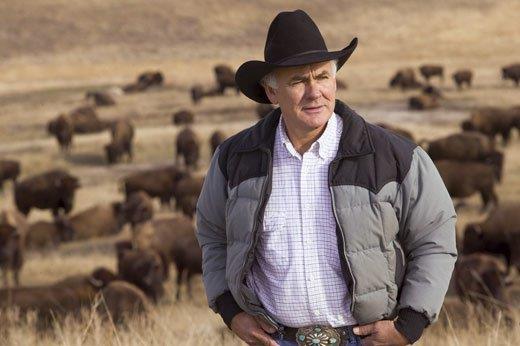

Johnson Buffalo Herd, Jim Strand Manager

Jim Strand takes a break in the Shadehill, South Dakota, pasture with Hoolie his saddlehorse to chat with Billy Bob, his latest bottle calf. Jim is manager of the 400-cow Blair Johnson buffalo herd. Photo credit Donna Keller.

On the trial run we stopped to visit Jim Strand’s live buffalo herd and drove among them, while Jim circled them with the feed wagon, which the buffalo knew brought a tasty snack. They came running over the hill—the bulls grunting and groaning in their own way. Photo by RF.

Larry and Erik said they loved being in the middle of the buffalo herd. Our visitors always do. In our tours we’ve found that’s a favorite—whether local old timers or tourists from afar—as long as they know they’re safe. Staying on the bus with the windows open for shooting great photos and videos to their hearts content! Photo RF.

Being in the midst of it gave the historians a chance to watch individual cows, bulls and calves close-up. Red dogs are what forest rangers call these young bison calves that are still cinnamon colored. They dazzle in the sun. By about 3 months of age the hump and nubbin horns begin to appear and their coats change to dark brown or black like their moms. Photo RF.

Hiddenwood Hunt Historic Site

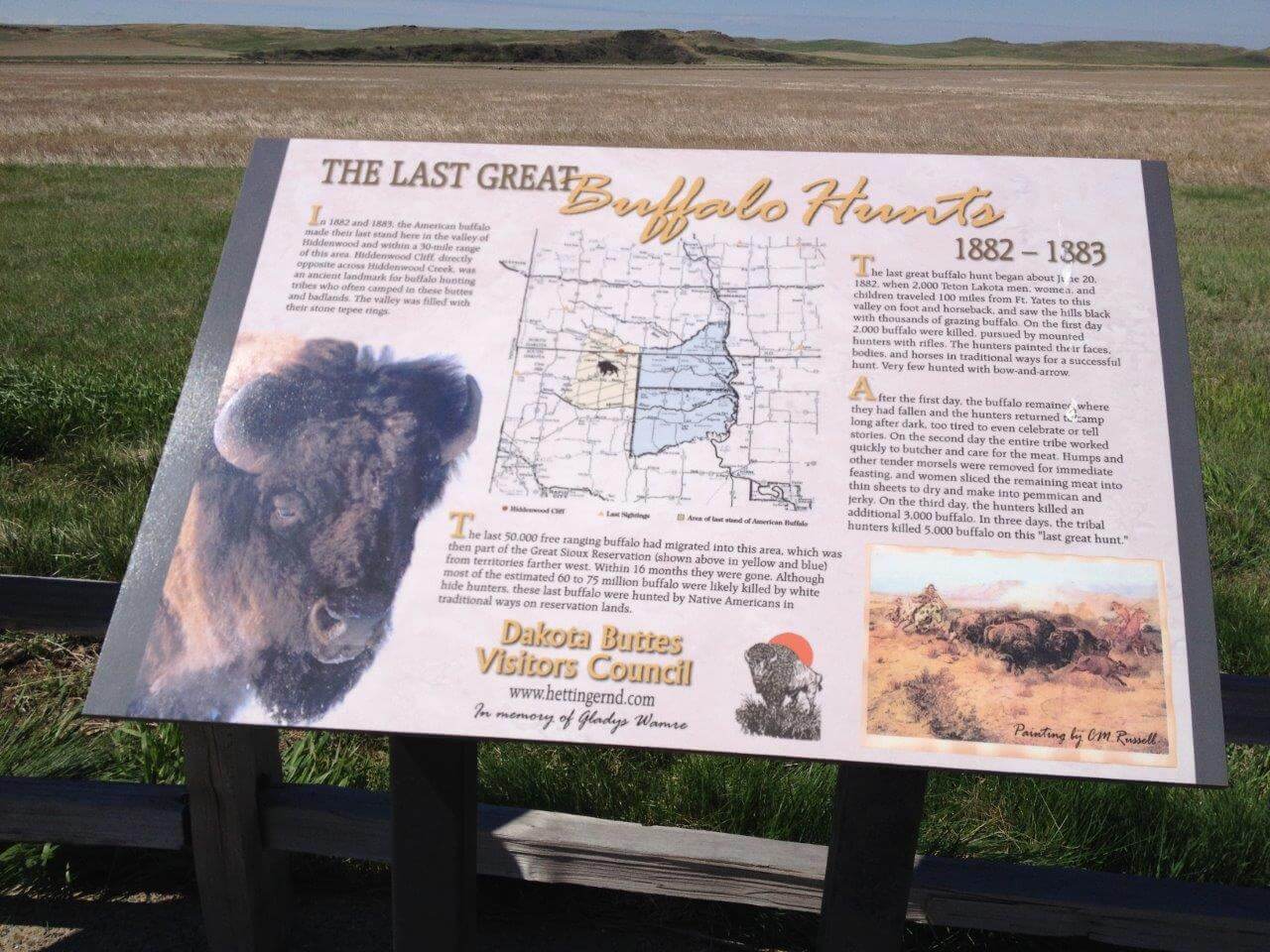

Our historic site at Hiddenwood on US Highway 12 halfway between Hettinger and Lemmon honors the June 1882 hunt in this wide valley. At that time 2,000 men, women and children travelled here from Ft. Yates and over 3 days killed 5,000 buffalo. Their Indian Agent James McLaughlin came along and described that hunt in detail in his memoirs. Photo FMB.

One of the signs at Hiddenwood explains 2 major historical events that happened here.

In 1874, Lt. Col George Custer and his 7th Cavalry camped here on their expedition to check out claims of gold in the Black Hills. A few years later, in 1882, one of the last great buffalo hunts took place at Hiddenwood.

For each event about 2,000 people camped here. For hundreds and thousands of years this was a famous campground for many plains tribes hunting buffalo. Photo FMB.

Last Stand–The Sitting Bull Hunt

This is where the American buffalo made their last stand—in this remote and beautiful valley of the North Grand River and others like it within a radius of perhaps 30 or 40 miles. These US Forest Service lands look much as they did 150 years ago when it was home to the last wild buffalo herds.

In the distance you see long ridges stretching across the horizon from east to west in waves, each wave a long divide of peaks, plateaus and flat-topped buttes splashed with shades of violet, lavender and blue. Each successive wave a paler shade as it recedes into the background.

A reporter riding through here with Custer declared he could see “no less than 40 miles.” He wrote, “The view is fine indeed . . . The well-defined, sharpened lines projected on the sky by rolling prairies and distant buttes is marvelous beyond expression and can never be appreciated unless actually seen.” Photo credit Kendra Rosencrans.

We know the dates and successes when Sitting Bull and his hunting party came here and killed the last great wild herd—1,200 buffalo died on October 16 and 17, 1883.

We don’t know precisely where, but it was certainly here or within a few miles of this place. Early settlers called this the Butchering Site, because of the many buffalo skulls and bones lying around.

Leg bones like these, found here, had invariably been smashed open to extract bone marrow. Photo FMB.

5:30 Dakota Buttes Museum (Hettinger)

Did Larry and Erik want to see more buffalo sites? “It’s just enough. Not too much!” they said. So we headed to the Dakota Buttes Museum to see Prairie Thunder first of all—our full-mount buffalo bull, donated by a local Bison rancher.

He was shot by a hunter who won the raffle to shoot it in the coldest week of January when the hide was at its best. Photo Dakota Buttes Museum, by Joel Janikowski.

You will finish off your BSC Dakota Bison Symposium tour in the Dakota Buttes Museum with a delicious buffalo dinner the evening of Friday June 24. Then back on the bus for your ride back to Bismarck. Photo Credit Melissa Lewis.

Sign up and Resources

More info from Erik Holland—What’s the follow-up?

“One of the pieces in getting graduate credit is for teachers to write a couple of pages in a very personal way about the material and how they plan to use it in their classes,” Holland says. “How they can think about the experiences they’ve had and what they are getting out of this. Each in your own way that connects all this.”

If you want Grad Credit:

- Sign up online with University of Mary at https://bscdakotabison.com/register/graduatecredit/), cost $45

- Attend the entire conference

- Write a short essay describing how materials and experiences of the BSC Bison Symposium will help you and your students get familiar with America’s National Mammal while aligned with the North Dakota Social Studies Standards

- Submit your essay to Erik Holland, Teacher of Record (701-328-2792) email eholland@nd.gov His office is in the ND Heritage Center and State Museum (https://statemuseum.nd.gov) and part of his duties relate to North Dakota social studies curriculum available at (https://NDStudies.gov)

You’ll go home with plenty of resources:

Our Dakota Buttes Visitors Council 88-page book, “Buffalo Trails in the Dakota Buttes: Self-Guided Tour” which I wrote in 2017 gives information on the 8 historic and contemporary bison tour sites in our area. Plus to complete anything we might have missed, we suggest you visit Fort Yates on the Standing Rock Reservation and the National Buffalo Museum in Jamestown, ND.

In addition you’ll have lots of brochures, videos and movies available to borrow or buy and access to online learning and curriculum sites. From all this you choose what you deem most valuable for your classes. Store the rest for later or for student research as opportunities arise.

You’ll have the resources you need to revisit these places and buffalo in your own community with knowledge you’ve never had before.

Holland has another idea: “Teachers who bring their own children to the symposium can think about ways to engage them in presenting the buffalo—and related Native American—experiences to their classes.”

He says the topics presented over the course of three days will provide information that can be used to align class materials with all social studies standards as directed by North Dakota Century Code 15.1-21-01: North Dakota Studies course requires that each ND public and nonpublic elementary and middle school provide students instruction in North Dakota studies, with an emphasis on the geography, history and agriculture of the state in the fourth and eighth grades.

“This event is a continuation of BSC’s work to bring humanities to the entire community,” Larry Skogen, BSC President Emeritius added. “We have a lot of really good partners in this event including the BSC Foundation, Indigenized Energy, NATIVE Inc, the State Historical Society of ND, and the Rockstad Foundation.”

We who made the trial run hope our timing that summer day was just right. Enough, and not too much.

Loren and I hope you’ll come back again. Bring your family, relatives and friends, to enjoy what you didn’t get to see this time!

##

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog