Join Us in Celebrating National Bison Day!

Photo from NationalDaysToday.com.

First, we have a buffalo story that you can tell your children and friends to celebrate National Bison Day!

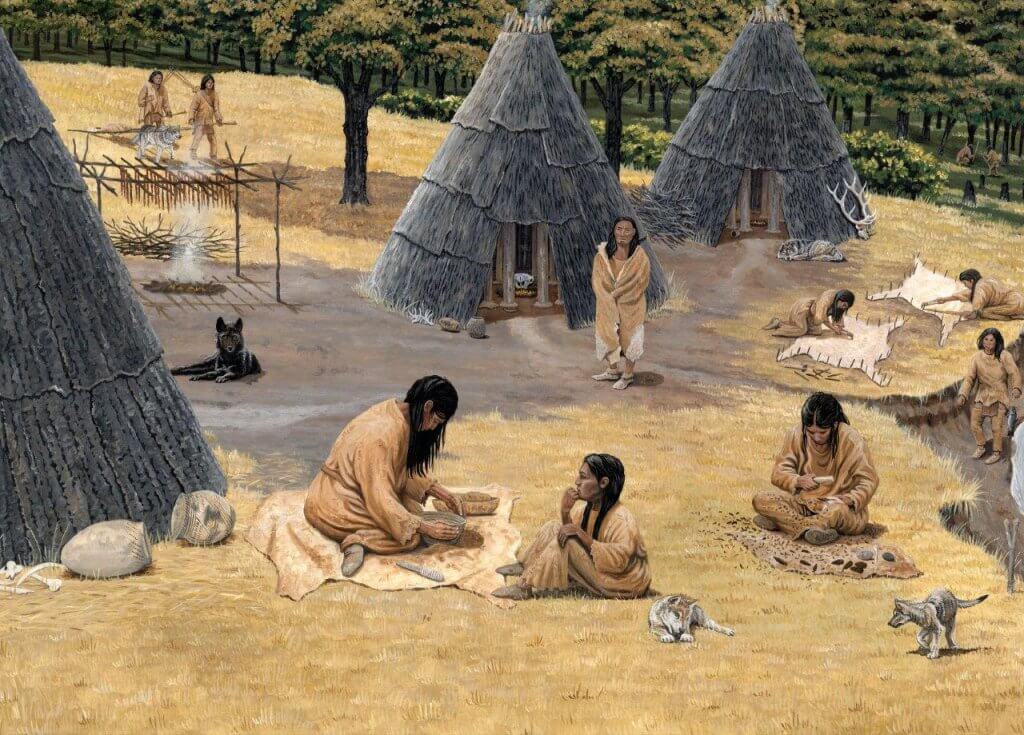

Traditional storytellers believe that old stories are best told in the Native language and to listeners who understand their culture.

They say an amusing story is “not as funny” in English. Much of the spirit, humor and excitement gets lost in translation.

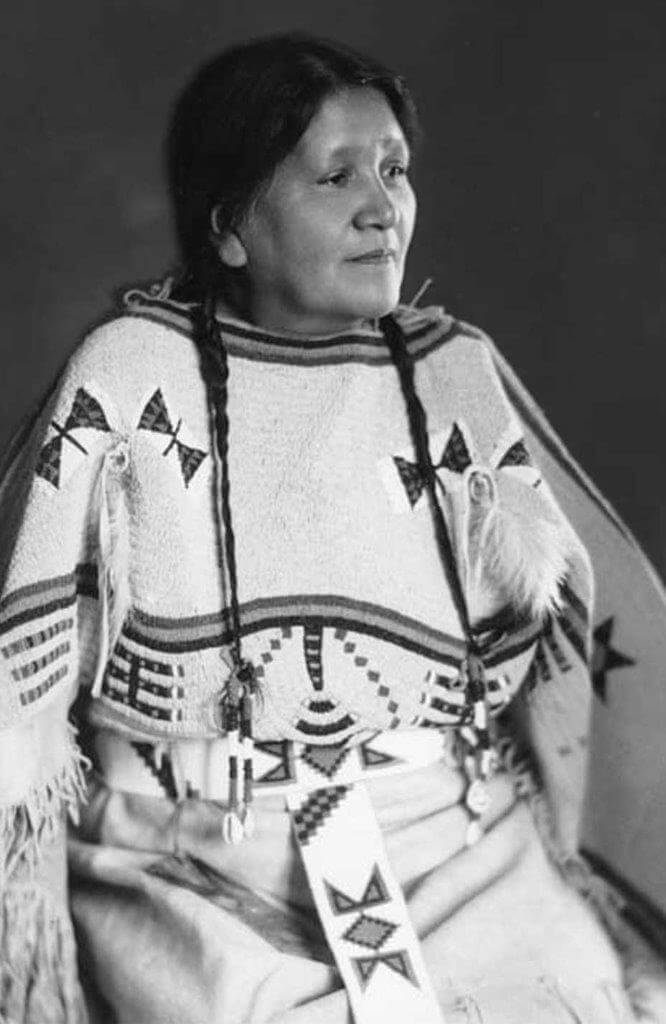

Often the venerable grandmother with a twinkle in her eye entertained with hilarious tales about coyote tricksters and other mischief.

This story may have been told just for fun with its twists, turns and surprises, by a grandmother to a giggling circle of attentive children seated around her.

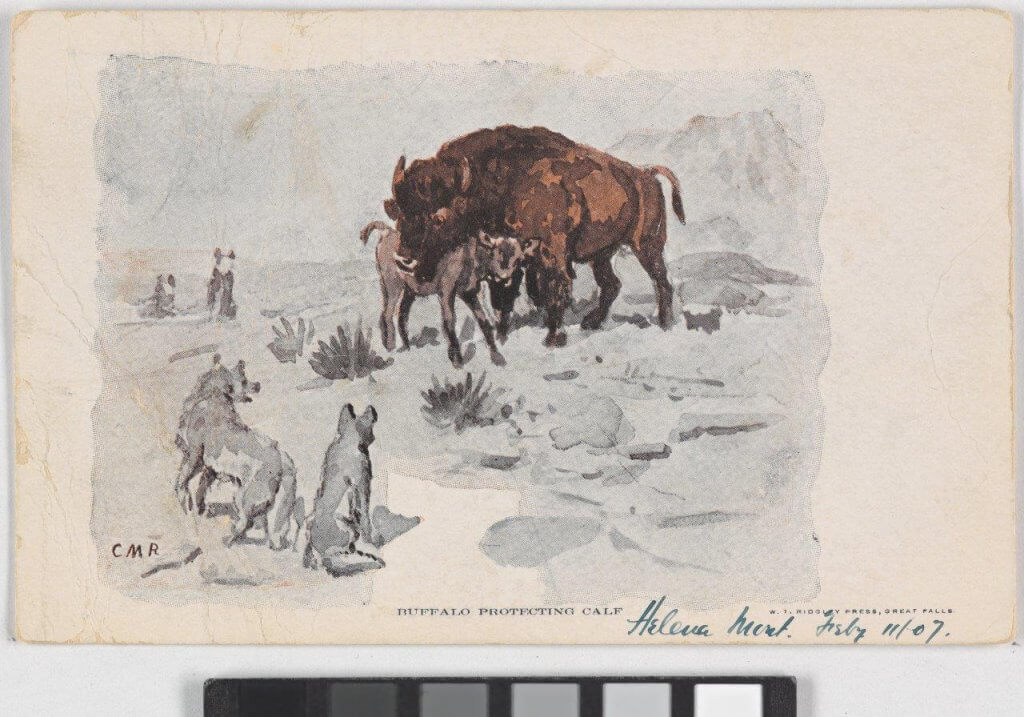

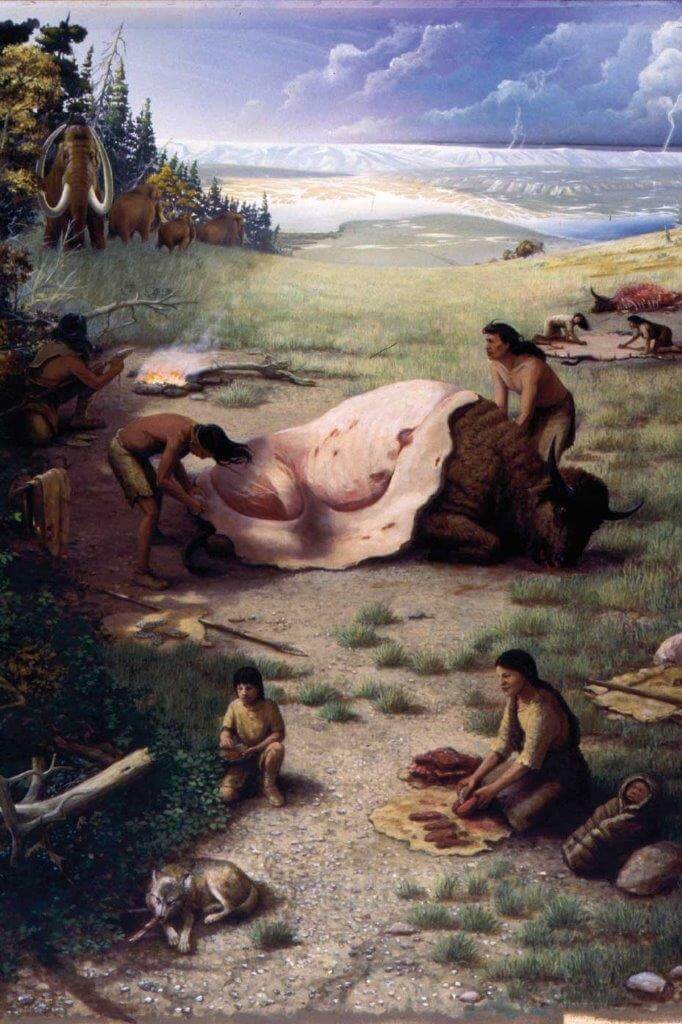

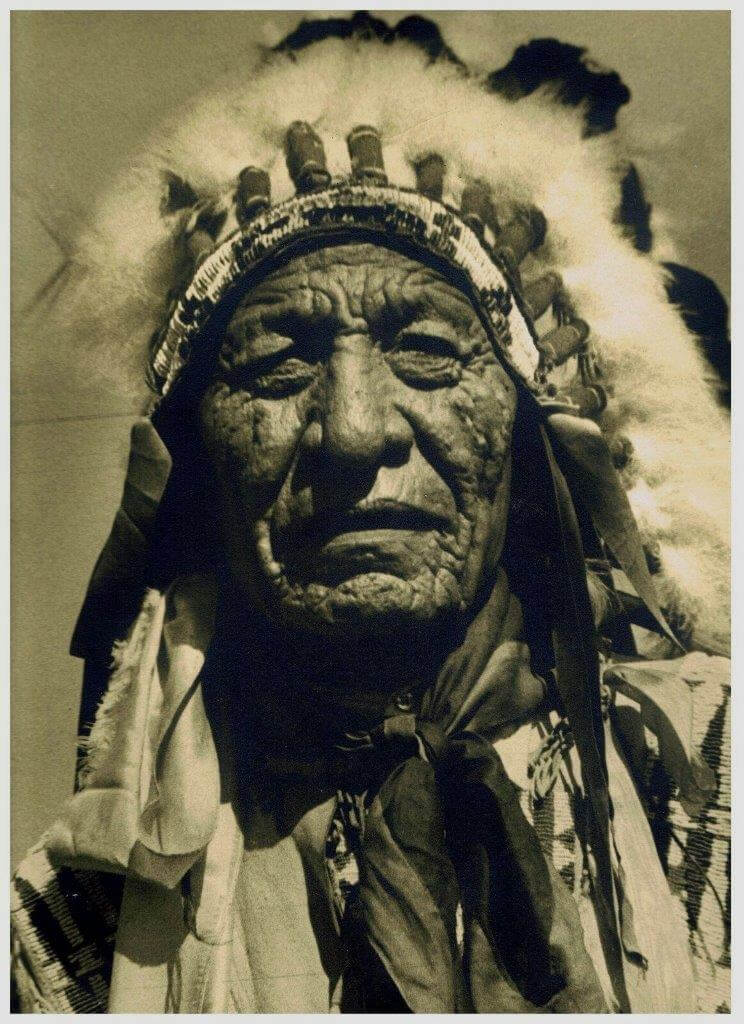

Buffalo was largest and strongest of all. He was hungry and wanted to be chief—the grandest of all animals and people. So he challenged the Native People to a race. Photo credit Chris Hull, SD Game Fish Parks.

Race Between Buffalo and the People

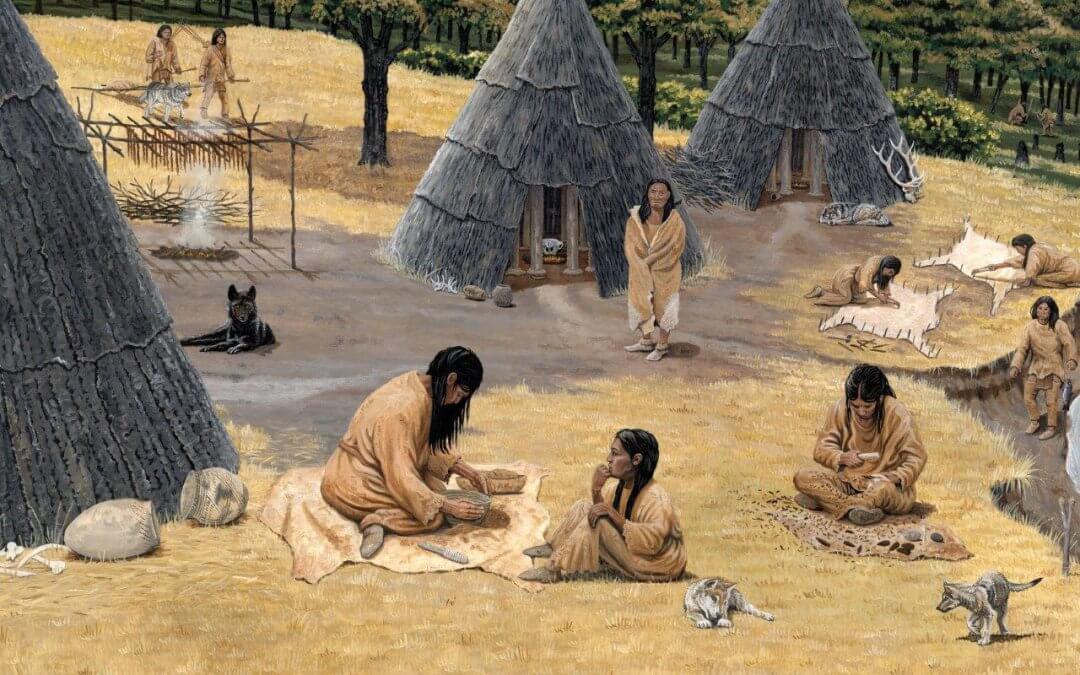

Many years ago all the animals lived in peace. No one ate anyone else. All the animals were the same color, because they had not yet painted their faces.

Buffalo was the biggest of the animals and he was getting hungry.

He wanted to be chief of all the animals and to draw strength from all the other animals by eating their flesh. Buffalo wanted to become the grandest of all the animals.

He said he deserved this as the largest and strongest of all.

But the Native People disagreed. They wanted to pull strength from the other animals and become the most important.

So buffalo challenged the Human People to a race. The winner would become chief of all the animals.

The People said they would accept this challenge, but since buffaloes have four legs and People have only two, the Native People claimed the right to have another animal run the race in their place.

The buffaloes consented.

In this story the Buffalo challenged the Native People into a race. The winner would become chief of all animals and could eat all others. Photo CH SDGFP.

The People chose Bird People to represent them in the race. They selected Hummingbird, Meadowlark, Hawk and Magpie.

All the other animals and birds wanted to join the race, too, each of them thinking that just maybe they too had a chance to become chief of all the animals.

All the animals took paint and painted their faces for the race, each according to his or her spiritual vision.

Skunk painted a white stripe on himself as his symbol for the race.

Antelope painted himself the color of the earth. Raccoon painted black circles around his eyes and around his tail. Robin painted herself brown with a red breastplate for the race.

The race was to be held at the edge of the Black Hills at the place known as Buffalo Gap.

The competitors would race from the starting line sticks to the turn-around stick and then back to the starting line.

All the animals, painted according to their vision, lined up between the sticks.

Among the animals were the Bird People—Hummingbird, Meadowlark, Hawk and Magpie—who would run the race with their wings for the Human People, and Runs Slender Buffalo, the fastest runner of all the buffalo.

The cry was given to begin and all the animals and birds burst from the starter stick.

Hummingbird took the lead, ahead of Runs Slender Buffalo, but his wings were so small that he soon fell behind.

As the animals neared the turn-around stick, Runs Slender Buffalo took the lead. Then Meadowlark came up beside Runs Slender Buffalo, and the two went along side by side right into the turn.

Runs Slender Buffalo wheeled around the stick, his hooves thundering, and he pulled away from Meadowlark, who flew wide to make the turn.

The animals in the lead passed the late runners who were still headed for the stick.

Meadowlark fell behind and cheered on Hawk as he passed her.

Hawk gained on Run Slender Buffalo, and it looked like she might pass him. His heart was pounding and his legs were tiring. But Hawk’s wings were tiring also, and she soon fell behind.

Runs Slender Buffalo was nearing the finish line as the winner.

It looked like the Buffalo would become eaters of all the other animals!

Then, behind the Buffalo, wings beating steadily, came Magpie. She was not a quick starter, but her wingbeats were hard and true. Her heart was strong. Her eyes did not wander from the finish line.

She never looked back. Her wings were wide and she drove herself forward with beat after beat after beat.

All the other animals had fallen behind. Runs Slender Buffalo looked over at the magpie, but Magpie never looked away from the starting sticks.

With each beat of her wings she moved past Runs Slender Buffalo by no more than the length of her bill.

At the starting sticks, many animals began to line up to watch the finish.

Raccoon, who had fallen out of the race early, had returned to the starting sticks.

Now he stood up between the sticks and put out his little hands for the runners to touch as they passed. He would feel the touch of whoever was in the lead, and turn toward the winner.

Closer and closer came Runs Slender Buffalo and some of the animals feared Raccoon would be trampled.

Magpie gradually flew nearer to the ground so she could brush Raccoon’s little hands as she flew past. Raccoon did not move, but stared straight at the onrushing pair.

Magpie seemed to be pulling ahead. Runs Slender Buffalo leaned forward as he ran to touch Raccoon’s hand with his great nose.

But Magpie’s wingtip touched Raccoon’s little hand and he turned toward her an instant before Runs Slender Buffalo thundered past, surrounded by a great cloud of dust. All the animals waited breathlessly for the dust to settle.

At last, there stood Raccoon with his little hand raised toward the path of Magpie.

The Human People had won the race!

Thus, the Native People became great hunters and chief of all animals. They feasted on buffalo meat while the Buffalo wandered the great plains eating grass and chewing their cud.

But the Native People never ate the Hummingbird, Meadowlark, Hawk or Magpie, who had befriended them and won the race for them!

(http://www.ilhawaii.net/~stony/lore122.html )

“They took care of us when we needed them; now it’s our turn to take care of them!” say many Native Americans. Photo CH SDGFP.

The Magnificent Buffalo

You see them everywhere—on coins, on sports team logos, on T-shirts and a couple of state flags.

No, we’re not talking about the bald eagle. This honor is reserved for North American bison.

On National Bison Day, November 5, an annual event that falls on the first Saturday in November, all Americans should reflect on the impact bison have as a part of our environmental and cultural heritage.

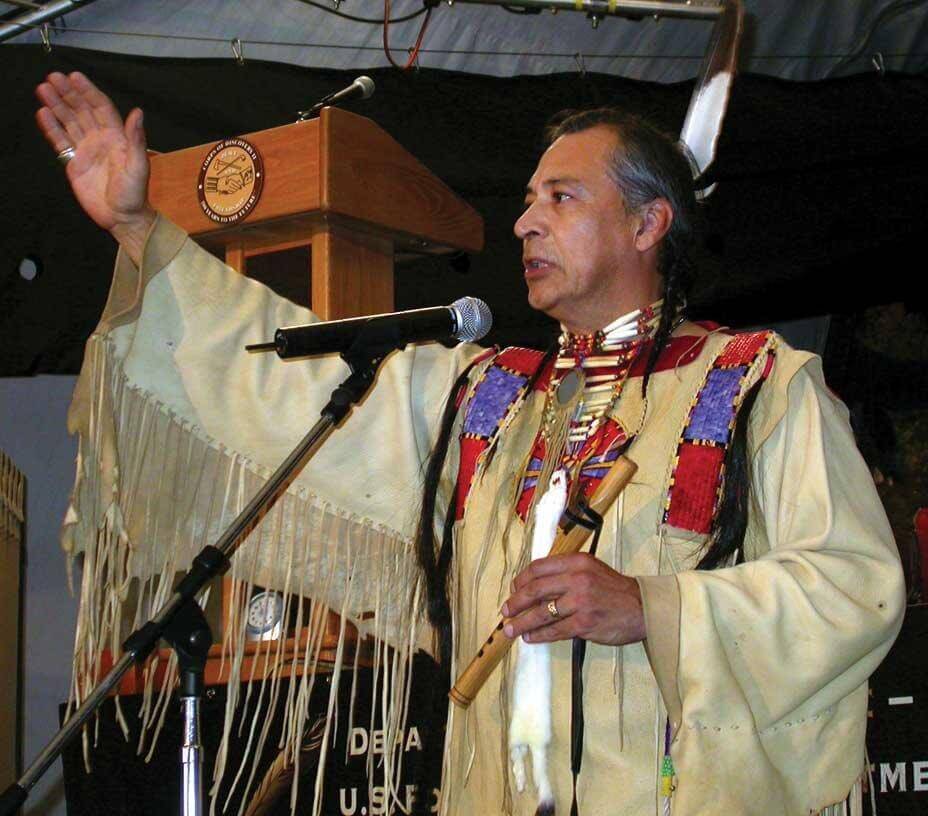

Bison are especially revered by Native People—for thousands of years central to their survival as both food and spiritual inspiration.

Today many Native Americans say, “They took care of us when we needed them; now it’s our turn to take care of them!”

The American Bison was officially named the national mammal of the United States on May 9, 2016, after a unanimous bipartisan vote in the US Congress. This majestic animal joins the ranks of the Bald Eagle as the official symbol of our country—and much like the eagle, it’s one of the greatest conservation success stories of all time.

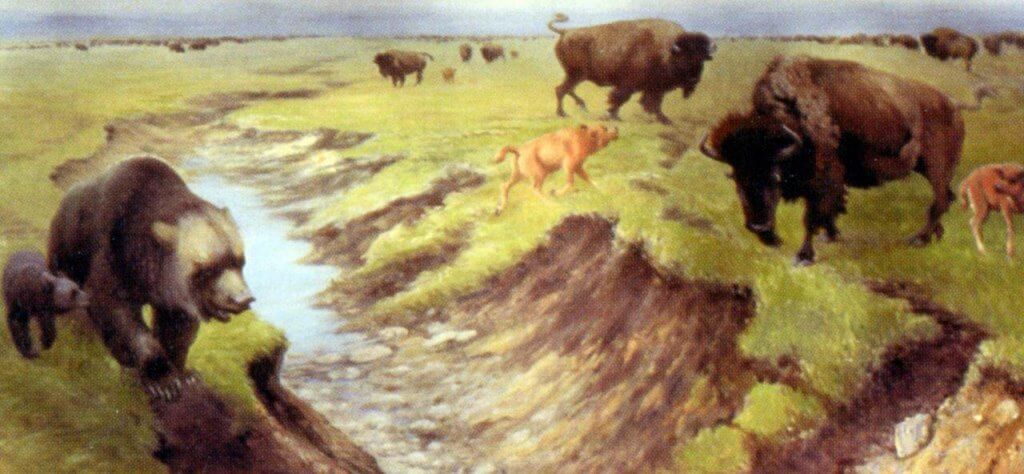

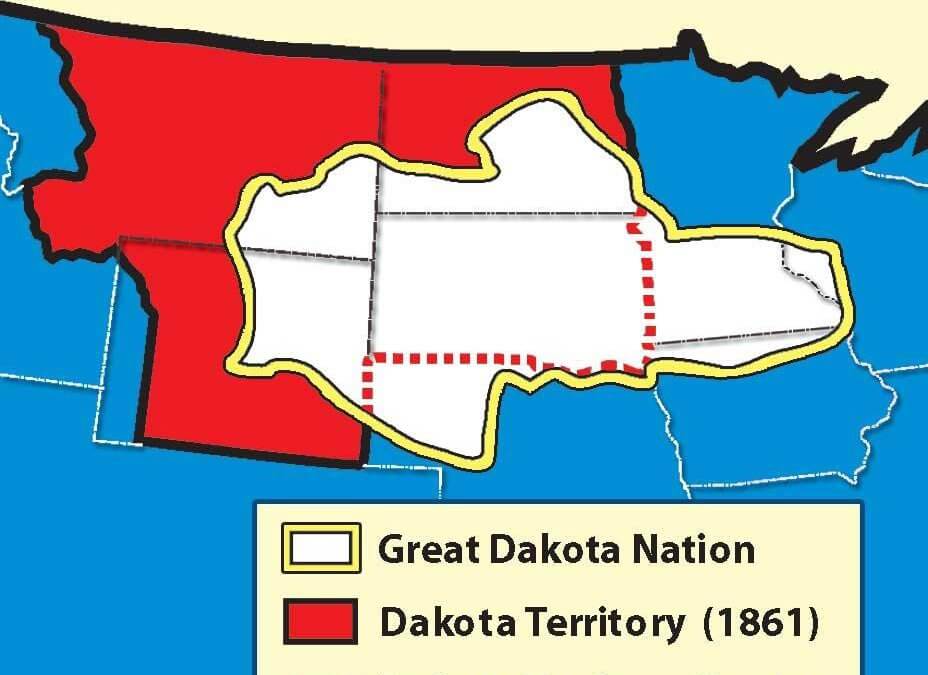

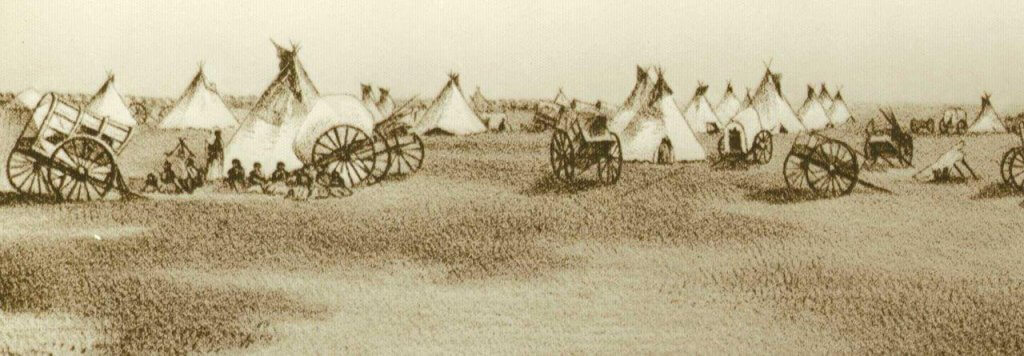

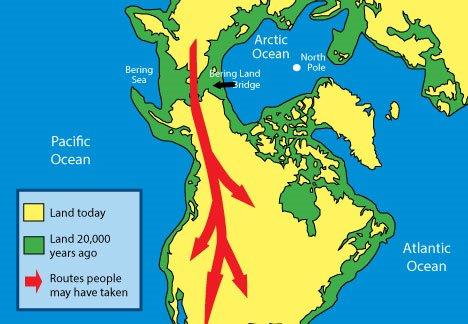

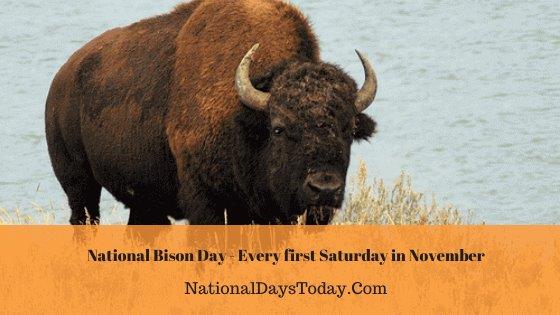

In prehistoric times, millions of bison roamed North America—from the forests of Alaska and the grasslands of Mexico to Nevada’s Great Basin and the eastern Appalachian Mountains.

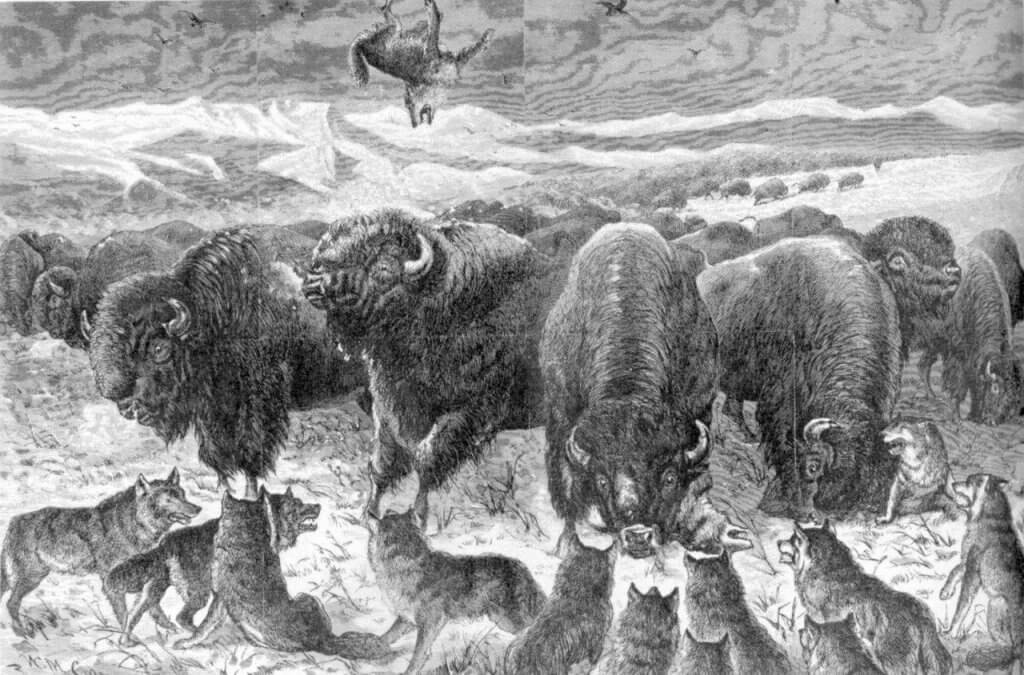

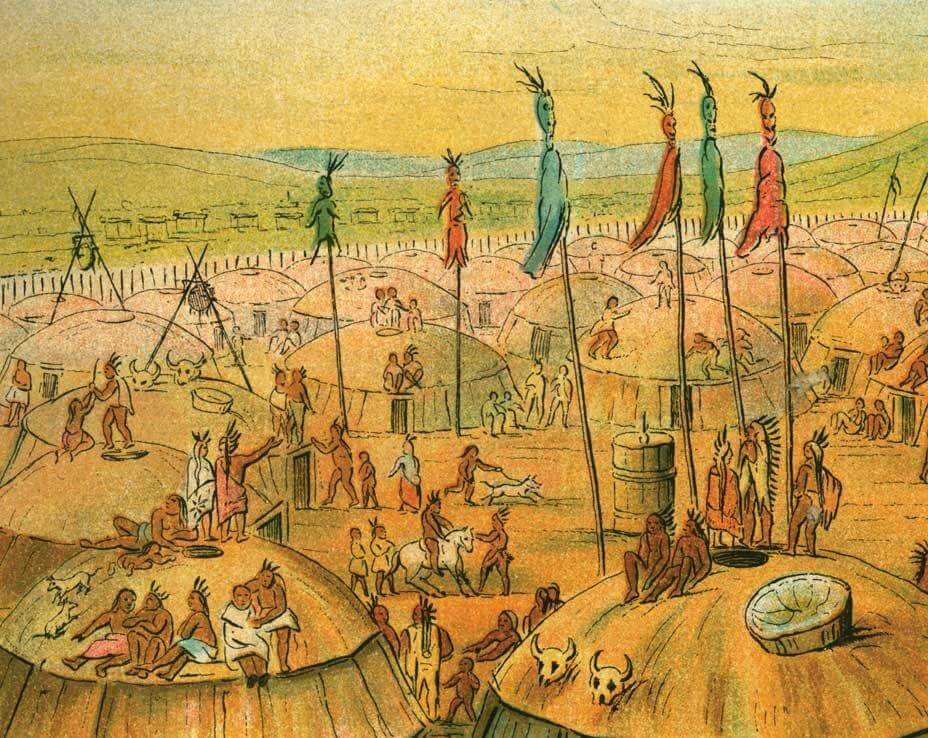

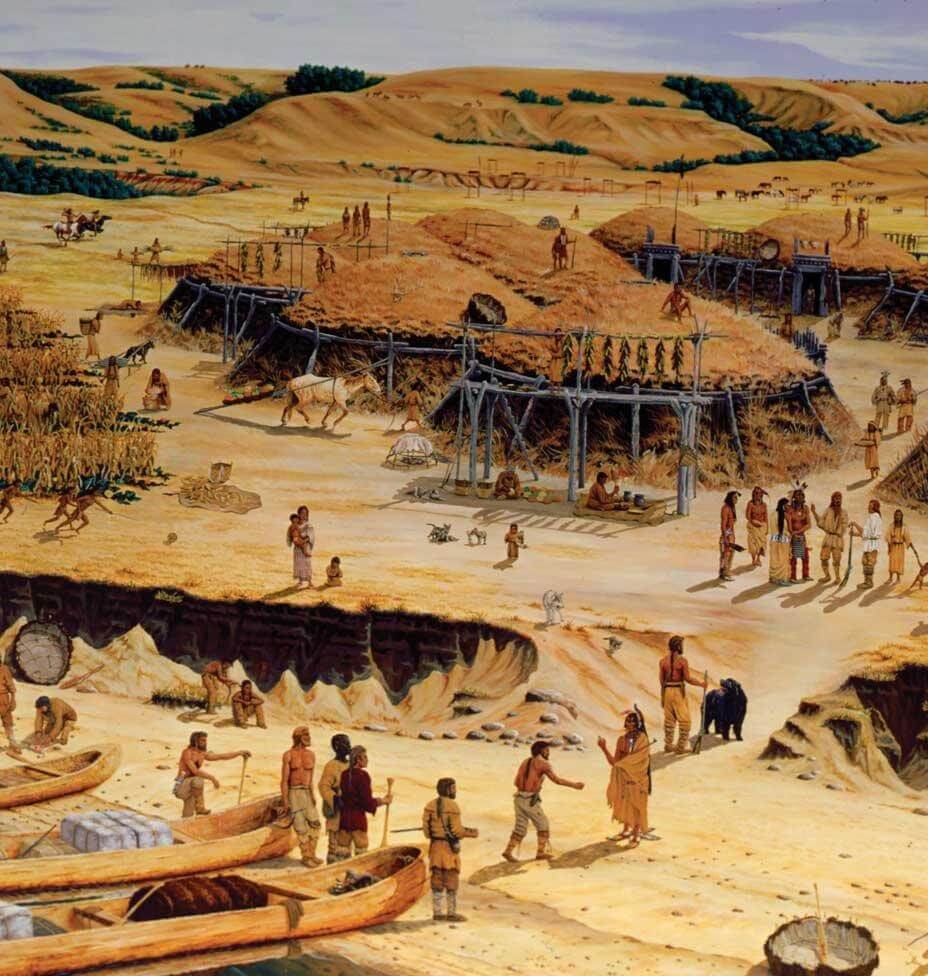

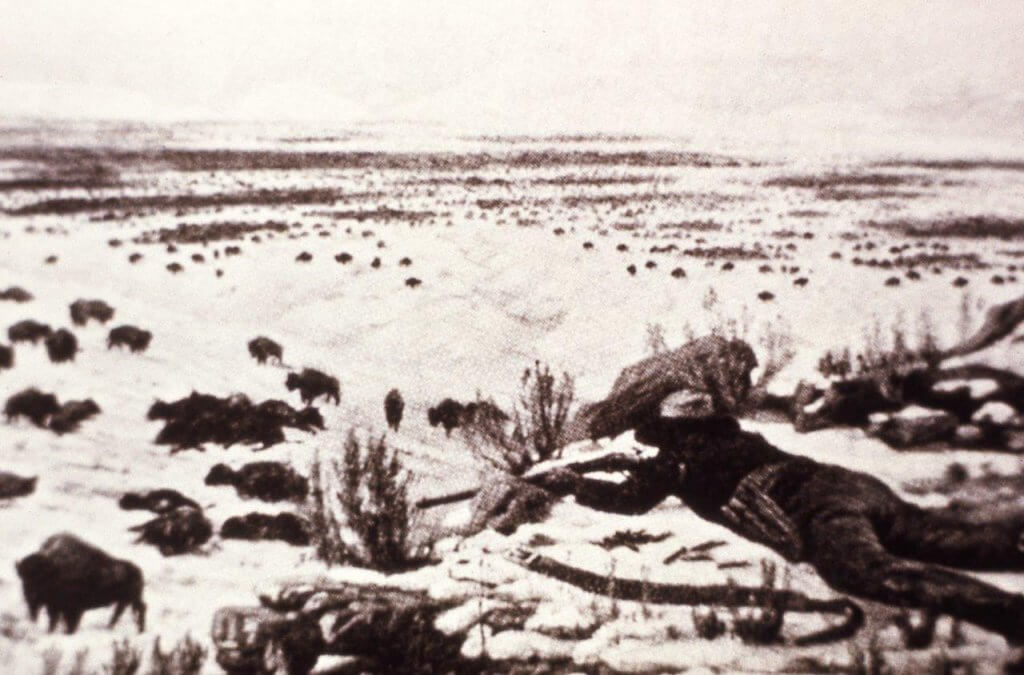

Millions of buffalo roamed North America. However, even in stampede they never crowded together quite as tightly as imagined in this ‘Eye-Witness Account,’ drawn by M S Garretson. They’d have been shredded by heavy, sharp horns on every side. Courtesy Kansas State Historical Society, Dave A Dary, The Buffalo Book.

But by the late 1800s, there were only a few hundred bison left in the United States after European settlers pushed west, reducing the animal’s habitat and hunting the bison to near extinction.

With powerful newly-developed guns the still hunt was deadly. The hunter made a stand from a point above the herd, bracing his rifle. The secret was to shoot leaders that tried to escape, while other buffalo milled around in confusion until all were slaughtered. Hides were stripped off and the meat left to rot across the plains. Sketch by JH Moser from William Hornaday’s ‘The Extermination of the American Bison.’

Had it not been for a few private individuals working with tribes, states and the Interior Department, the bison would be extinct today.

What to do on National Bison Day!

Celebrated on the first Saturday in November. This day is observed to honor the majestic beasts of the United States.

1.Tell buffalo stories to your family, your friends, at the Senior Center, your office or on the Radio or TV. Everyone enjoys a buffalo story.

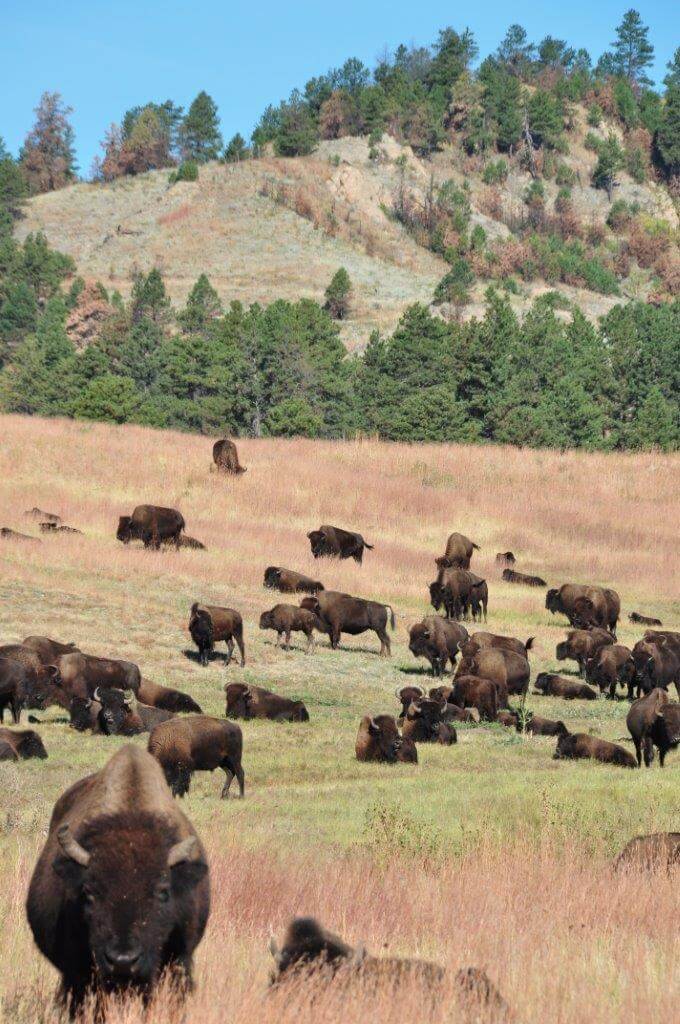

2.Visit a national park, or a nearby buffalo herd. You may not be able to get to a large national park like Yellowstone, but every state and Canadian province has a buffalo herd or two—or more. There are a vast number of parks from which to choose, and many have buffalo. So get acquainted and ENJOY watching live buffalo.

Every state and Canadian province has a buffalo herd—or several. Give your children the opportunity to experience the wonder of our latest national icon—the Bison. Photo the large Johnson herd near Shadehill in South Dakota.

Give your children a chance to experience the wonder of our latest national icon—the Bison or Buffalo. Imagine what it must have been like to see thousands of them freely roaming the plains!

3. Wear a buffalo T-shirt. It won’t be hard to find a T-shirt that shows your love of bison. Wear it proudly because we only have one national mammal. It’s a majestic symbol to wear—or maybe a cute bison cartoon.

4. Many groups use this day to raise funds in support of bison. You can help.

5 Reasons We Love Our Bison

1. Watch that tail

If a bison’s tail is hanging down and moves naturally from side to side, the animal is relaxed. But when the tail stands straight up, it’s a signal the buffalo is getting ready to charge. Too late to run!

2. They’ve got skills

Given their size as the largest mammals in North America, bison are surprisingly agile with an ability to swim well, jump up to six feet, spin on a dime (pivoting from their front legs, not the rear as do most animals) and run between 35 and 40 mph.

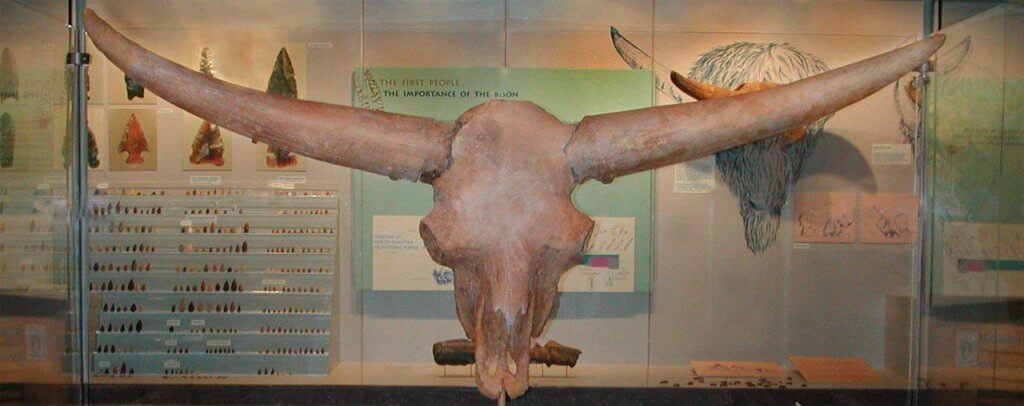

3. They’re oldies but goodies

Bison have always roamed in Yellowstone National Park as evidenced by prehistoric fossils found in modern times. But they were once cut down to about 24 head and replenished by buffalo from various sources.

4. Throw a stone—hit a bison

Herds of bison can be found in all 50 states.

5. Bison as symbols

The American bison is not only the country’s official mammal. It is also the state mammal of Wyoming, Oklahoma and Kansas. And yes, buffalo are found on coins, belt buckles, flags and jewelry!

Why National Bison Day is Important

Bison are our national mammal. Here are a few interesting facts about the Bison:

- Bison is North America’s largest land mammal

- Bison have a lifespan of 20 or more years

- The male Bison can grow up to 6 feet tall and weigh nearly 2000 pounds

- The female Bison grows up to 5 feet tall and weighs 1000 pounds

- Calves have a reddish coat at birth and are nicknamed “red dogs”z

Calves are cinnamon colored for the first three months, then nubbins of horns and a hump begins to grow and gradually they turn dark like their moms. Mothers are very attentive and keep their calves close by. Photo CH SDGFP.

- Fully-grown Bison will have shaggy coats that are dark brown to black

- Bison have a strong sense of hearing and smell but poor eyesight; However because they have an eye on each side of their head and can’t focus sharply, they have good peripheral vision to keep track of what’s behind

- The Bison’s hump is a composition of long vertebrae that support the muscle allowing it to plow through snow

- Fossil accounts reveal that Bison has been a native continuously to Yellowstone since the prehistoric period

- Bison can run up to 35 to 40 mph i.e., as fast as a horse. They can ‘spin on a dime,’ pivot quickly and jump high fences

- The Bison tail displays its mood. If it’s hanging down and swinging naturally, the bison is calm. If its tail is straight up, run for your lives

History of National Bison Day

National Bison Day was initiated in 2012 by conservationists and Native Americans with their concern for the American Bison. The resolution was headed by Sen. Michael Enzi and Sen. Joe Donnelly and co-sponsored by a mix of other senators.

It took 4 years, but Congress passed the National Bison Legacy Act in April 2016 with unanimous support. They set the first Saturday in November as National Bison Day.

This brought together the Vote Bison Coalition consisting of more than 50 Indian tribes, businesses, and organizations led by the Wildlife Conservation Society, National Bison Association, the InterTribal Buffalo Council, Both Native and Non-native bison producers, conservationists, sportsmen and educators to celebrate the significance of Bison.

The American Bison, also commonly known as the American buffalo, once roamed the grasslands of North America in massive herds, and became nearly extinct.

The bison are considered a historical symbol of the United States and were integrally linked with the economic and spiritual lives of many Native American tribes through their culture, trade and sacred ceremonies.

Bison are also known to play an important role in improving soil and creating beneficial habitat while holding significant economic value for private producers and rural communities.

The buffalo were saved from extinction by a very few individuals. Five family groups—three with Native American roots—deserve the credit. If they hadn’t acted in the way they did—rescuing buffalo calves, mothering them up with cows and growing their own herds—we’d have no buffalo today! Photo by Jim Strand.

Who really Saved the Buffalo?

Amazingly, saving the buffalo was in the hands of a very few individuals. All were western ranchers who also hunted buffalo. Five family groups in the US and Canada get our praise and international credit for saving the buffalo from extinction.

Three of the families had Native American roots. If they hadn’t acted in the way they did—to save individual buffalo calves, mother them up with domestic cows and grow their own herds—we’d have no buffalo today!

It is true that many groups stepped in to make permanent homes for the buffalo in parks, refuges and tribal herds, after local herds began thriving. We also honor them for their important follow-up work.

But let us never forget that it was the people who knew buffalo best—those Westerners with moccasins and boots on the ground—who rescued and fed fragile orphan calves, nourished them and grew them into viable herds and cared for them—who did the critical rescue work that saved the species!

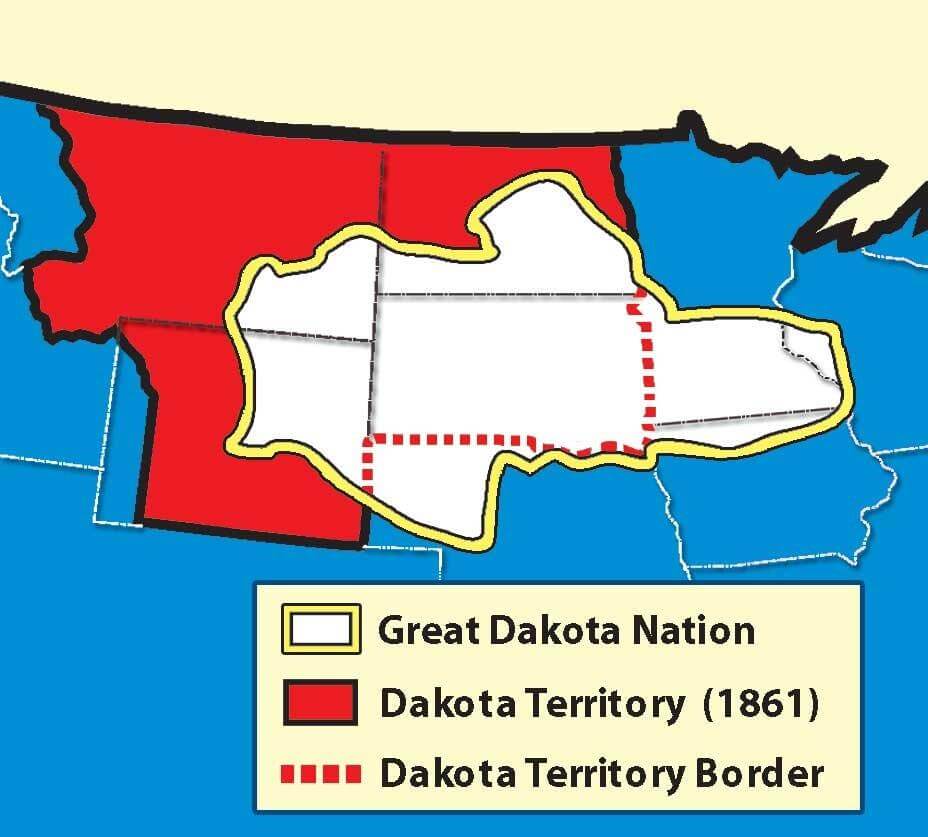

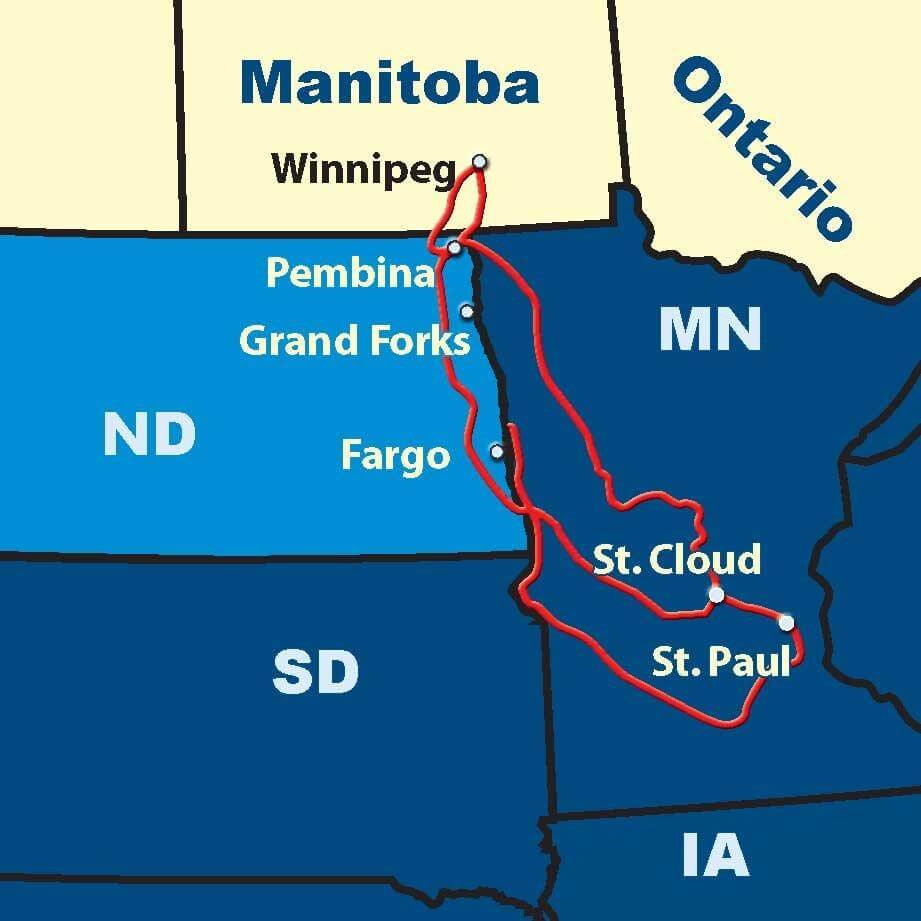

The Native American families were Pete Dupree in South Dakota, whose mother was Lakota Sioux, who grew his herd to 83 head until his death—and his herd purchasers Scotty Philip who also had a Native American wife. James McKay, a Metis from near Winnipeg. And the Native hunter who travelled from the Flathead reservation east across the Continental Divide in Montana to hunt buffalo with Blackfoot friends and brought back 4 live buffalo calves which grew into a herd of 13. (Some say this young hunter was Sam Walking Coyote; but others say Walking Coyote was the sneaky stepfather who sold the herd without the young hunter’s permission for $2,000.)

Charles Goodnight, cattle rancher from Texas and CJ “Buffalo” Jones of Kansas were the other two who first hunted buffalo, and then turned to their rescue.

Amazingly, saving the buffalo was achieved by a very few individuals. All were Western ranchers who also hunted buffalo. Three of the five family groups had Native American roots. Photo CH SDGFP.

- Amazingly, saving the buffalo was in the hands of a very few individuals. All were western ranchers who also hunted buffalo. Five family groups in the US and Canada get our praise and international credit for saving the buffalo from extinction.

- Three of the families had Native American roots. If they hadn’t acted in the way they did—to save individual buffalo calves, mother them up with domestic cows and grow their own herds—we’d have no buffalo today!

- It is true that many groups stepped in to make permanent homes for the buffalo in parks, refuges and tribal herds, after local herds began thriving. We also honor those people for their important follow-up work.

- The Native American families were Pete Dupree in South Dakota, whose mother was Lakota Sioux, who grew his herd to 83 head until his death—and his herd purchaser Scotty Philip who also had a Native American wife. Jaimes McKay, a Metis from near Winnipeg, and Walking Coyote or a young hunter from the Flathead reservation west of the Continental Divide in Montana.

- Charles Goodnight, cattle rancher from Texas and CJ “Buffalo” Jones of Kansas were the other two who first hunted buffalo, and then worked to save them.

A buffalo cow may weigh 1,000 pounds; while the bull might weigh twice as much, or up to 2,000 pounds! In the US we use the terms Bison and Buffalo interchangeably. CH SDGFP.

What should we call them—‘Bison or Buffalo?’

Bison, Bison, Bison!” admonish our European friends.

But just a minute! Yes, scientifically speaking our buffalo are named Bison. We know that. Of course.

Scientific names also apply to Equine, Bovine and Canine—that’s fine between scientists and veterinarians. But in conversation, we don’t call them that, do we? So let’s not get hung up on this technicality.

In the US we use the terms Bison and Buffalo interchangeably—and it’s OK.

Use whichever you like. But note it’s National Geographic usage; American dictionaries, most Westerners and certainly Native Americans prefer to use the term Buffalo, unless they’re saying it in their Native language.

Here in the west—and certainly all across America—we have towns and creeks and hills named after the buffalo.

In the county next to us we have two towns, ‘Bison’ and ‘Buffalo.’ Which is the more correct and more important? It’s a toss-up. The people there don’t seem to care. I think they are happy to share the honor.

‘Buffalo’ was a term first used in America in 1625. ‘Bison’ was documented here after 150 years later—in 1774.

The word ‘Buffalo’ actually came from early French fur traders and trappers who called the animals ‘les boeufs,’ a Greek word for ‘the beeves’ meaning oxen or bullocks. In that context both names, ‘bison’ and ‘buffalo’ have a similar meaning.

‘Buffalo’ even has a verb form—‘to buffalo,’ meaning to overawe or bewilder.

British friends say we are confused. I don’t think so.

Confusion is not really the issue. Neither is science—we understand and accept the science.

The thing is, we just like our buffalo. And we like to call them that. It fits.

William T. Hornaday, that great historian of the species, was good-humored about it. He called the animals ‘Bison’ in his own writings. Nevertheless, he wrote in 1889:

“The fact that more than 60 million people in this country unite in calling him a buffalo, and know him by no other name, renders it quite unnecessary to apologize for following a harmless custom which has now become so universal—that all the naturalists in the world could not change it if they would!”

Even more important to us: the word ‘Buffalo” rolls off the tongue in a friendlier, more comfortable way. ‘Buffalo’ fits these majestic, stoic and powerful beasts.

‘Bison’ doesn’t do that—it’s kind of a sissy word (unless you give it a ‘Z’ sound as do NDSU Bison football fans).

Curled 2-finger salute of North Dakota State Bison football fans—at upper left—denotes curved horns of a prized bison head. Fans also go hoarse shouting, ‘Go Bizon!’—Emphasis on the ‘Z’ to celebrate their football dominance. Photo by Mike Stone, OregonLive.

‘Bison’ sets barriers and keeps a cool distance between us and these beloved animals.

I think Professor Dale F Lott, University of California, said it best. He’s a scientist who grew up in the shadow of buffalo. He’s not confused about anything–most especially his beloved buffalo!

Born on Montana’s National Bison Range, where his grandfather was the Superintendent, Lott grew up watching buffalo on the hills every day. His father, from a nearby ranch, worked on the Bison Range. He had married the boss’s daughter.

Professor Lott, who in my opinion surely loved and understood the buffalo as much, if not more, than any other scientist who wrote of them, explains why he uses both terms interchangeably.

“I’ve given a lot of thought to whether I should call my protagonist ‘bison’ or ‘buffalo,’” he explains in the preface to his book: ‘American Bison: A Natural History.’

“I decided to use both names. My scientist side is drawn to ‘bison.’ It is scientifically correct and places the animal precisely among the world’s mammals.

“Yet the side of me that grew up American is drawn to ‘buffalo’—the name by which most Americans have long known it.

“’Buffalo’ honors its long, intense and dramatic relationship with the peoples of North America.”

Lott drops the discussion there. Enough said.

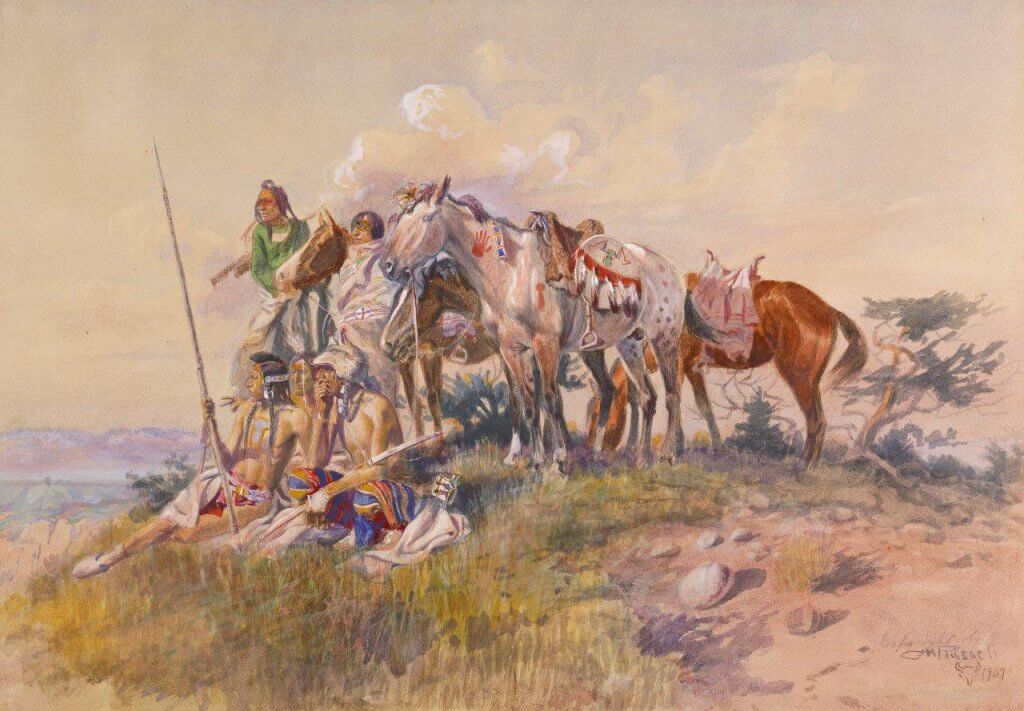

: According to all accounts Indian buffalo hunting horses were better trained for the job than those of white hunters, reported William Hornaday, our first great buffalo historian, in 1889. Painting of scouts by CM Russell, Amon Carter Museum.

So, when it all shakes out, what should we call them? These majestic, magnificent creatures of the Plains and Prairies?

My answer is this: Call them whatever you like, the term with which you are most comfortable—or use both interchangeably, as does Professor Lott.

Maybe ‘Buffalo’ when you’re with friends; ‘Bison’ when you’re with scientists.

Or just ‘Buffalo.’ Whichever feels right to you. But as Hornaday suggests, don’t apologize.

It’s a mistake for Americans to think we ‘should’ call our own Greatest Mammal whatever others tell us we ‘should.’

We can say, cheerfully, with a smile, no trace of rancor, “No, I don’t think so!”

To many of us, they are simply ‘buffalo.’

It fits. We know them well!

This is the name that honors the majestic animal itself.

Because it’s true: ‘Buffalo’ celebrates that “long, intense and dramatic relationship” they have with the Native people and settlers of North America.

And that’s the issue.

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog