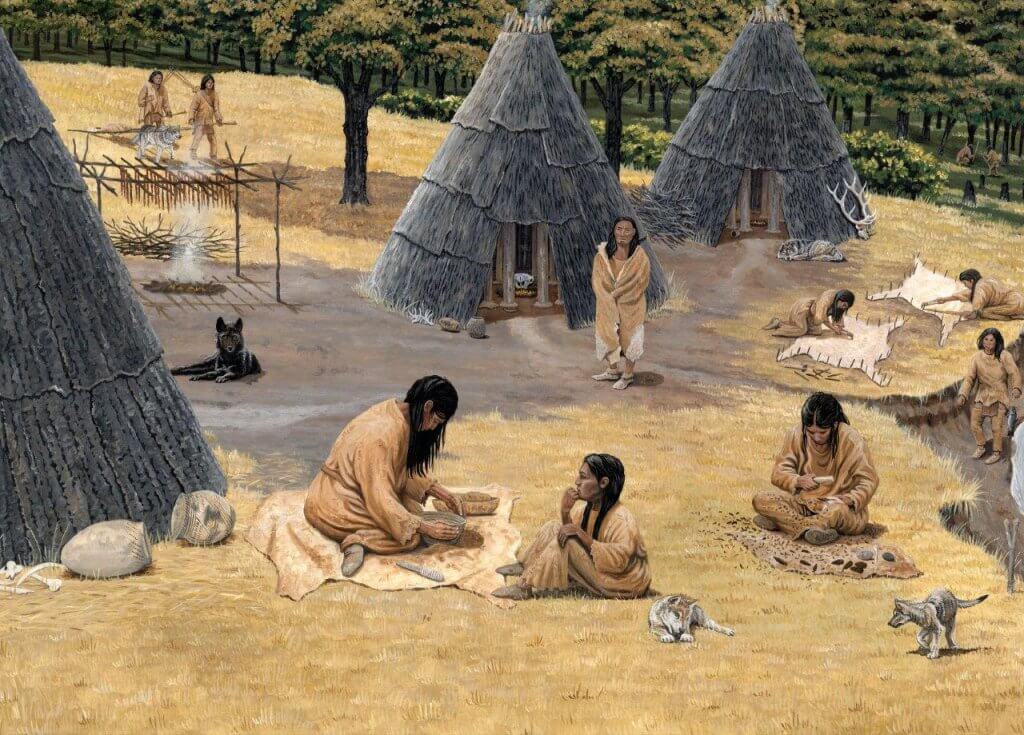

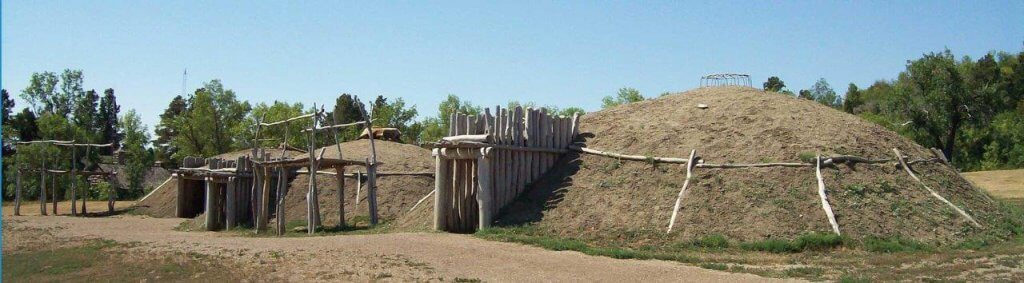

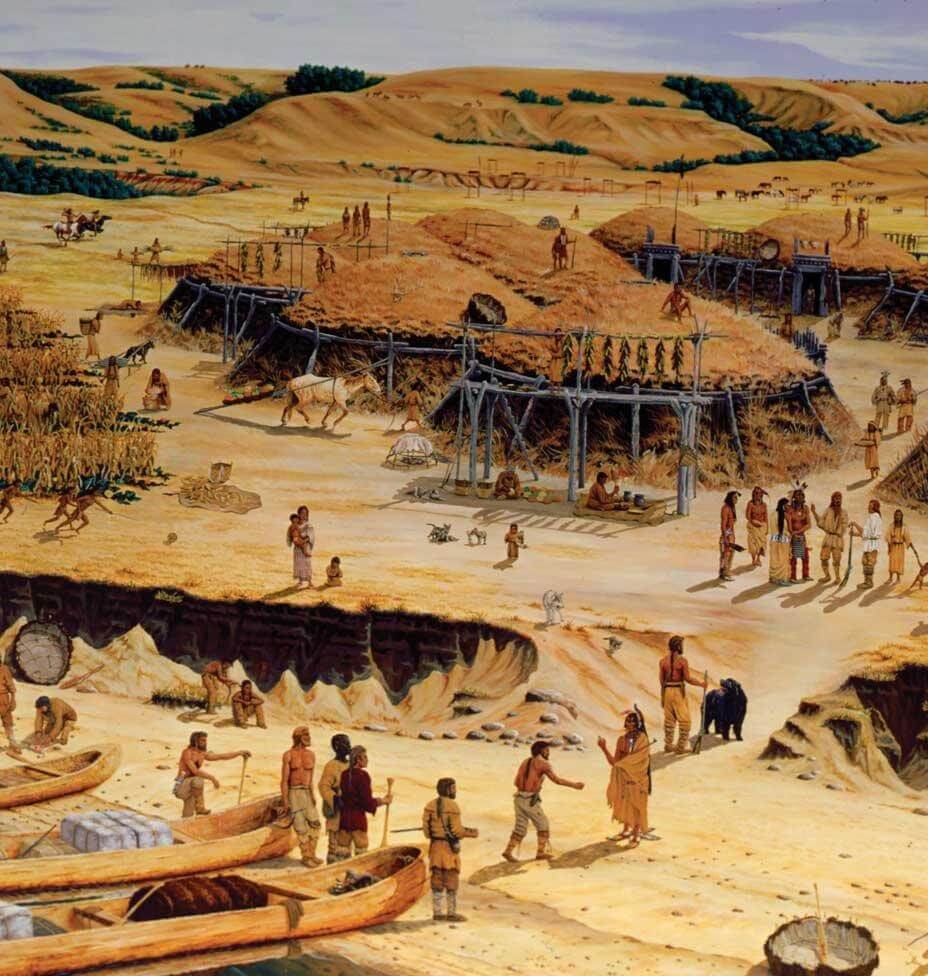

A Plains Woodland Camp Scene. Photo ND State Historical Society.

About 2,500 years ago, the people of the Woodland era appeared in North Dakota. These people came from the forests of Minnesota and Wisconsin.

The Woodland people hunted and gathered as the earlier groups had done and they got corn through trade. The Woodland people were the first people in North Dakota to make pottery.

Woodland People

The Woodland people lived mostly near rivers where they had a ready supply of drinking water. Trees and brush that grew beside the rivers provided firewood and served as habitat for game which could be hunted.

They protected their villages with walls made of upright logs.

Woodland pottery. Pieces of a pot found in North Dakota (right). Also shown is a replica of the pot (left). Pottery examples are on display at the North Dakota Heritage Center & State Museum in Bismarck, North Dakota. Photo Neil Howe.

Some of the Woodland people had houses that used wood frames covered with bison hides or grasses. The sites of a few Woodland villages have been found in North Dakota.

Another difference between people of the Archaic era and people of the Woodland era was in their burial traditions. In the Archaic era people placed their dead on platforms or under piles of rock. Some Woodland people buried their dead in the earth. After a body was placed in a grave, a mound of dirt was placed over the grave.

Sometimes weapons, tools, and other possessions were also placed in the mounds. These mounds became big cemeteries, and some were used for hundreds of years. This practice earned the Woodland people the nickname “Mound-builders.”

About 1,400 years ago, North Dakota became home to the Late Woodland culture. The Late Woodland people may have been ancestors to the Mandan Indians. They lived much like the earlier Woodland people, raising crops and hunting bison, but they also depended more on fishing.

We Are All Equal

The color of skin makes no difference. What is good and just for one is good and just for the other, and the Great Spirit made all men brothers. I have a red skin, but my grandfather was a white man. What does it matter? It is not the color of the skin that makes me good or bad. –White Shield, Arikara Chief

Notable American Indians of North Dakota

As you continue you will notice full-page tributes to notable American Indians of North Dakota. These people include Keith Bear, Mary Louise Defender Wilson, Sitting Bull, Sakakawea, Four Bears, Cynthia Lindquist, Josephine Gates Kelly and Louise Erdrich. Please study these tributes to learn how these North Dakotans have contributed to the history and culture of our state.

By 1500, or even earlier, American Indians of North Dakota had organized into tribes, or groups of people who have a common heritage. The people of an Indian tribe share a culture or a way of life that includes language, traditions and religion. A tribe’s oral traditions, or storytelling, help the people understand their common history and traditions. Culture makes each tribe different from all other tribes. Each tribe also identified a particular area of land where they lived and hunted.

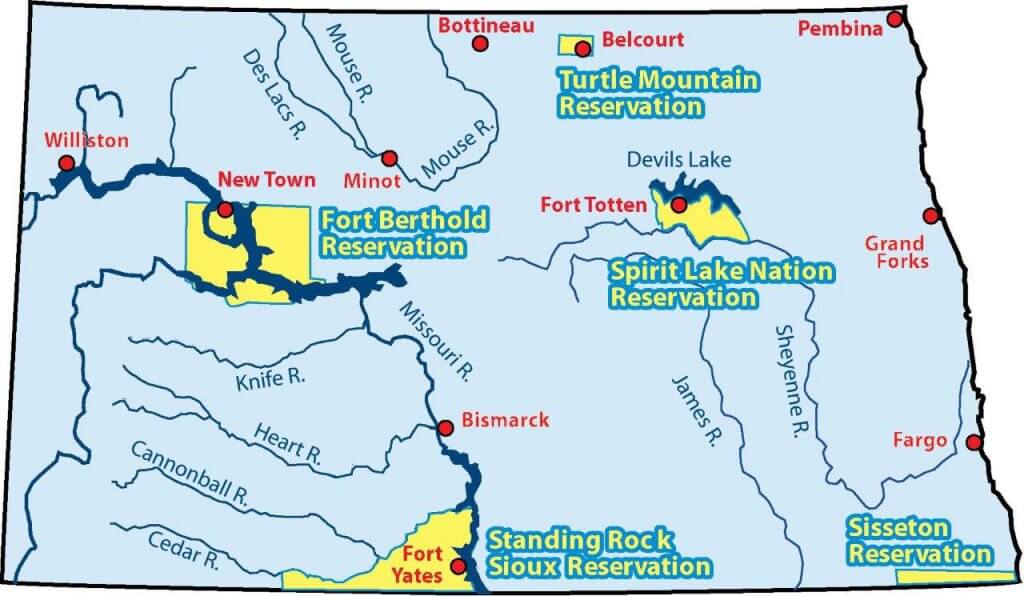

Today there are six tribes with headquarters in North Dakota. They are the Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara, Lakota Sioux, Dakota Sioux and Turtle Mountain Chippewa. The Lakota, Dakota, and Chippewa are related to other bands of their tribes that live in other states.

Six tribes have headquarters in North Dakota—the Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara, Lakota Sioux, Dakota Sioux and Turtle Mountain Chippewa.

Plains Village People—Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara

The Mandan and Hidatsa people lived in villages of earthlodges. The earthlodge was a dome-shaped home made of logs and covered with willow branches, grass, and earth. The women built, owned, and took care of the homes. They also owned the property within the homes, as well as the food, gardens, tools, dogs, mares (female horses), and colts (young horses). When a couple got married, the man moved into his wife’s home. He brought only a few things along, such as his medicine bundle, clothes, weapons, and horses. The men were responsible for protecting the village and hunting for meat.

A cache pit was used to store dried corn, nuts, berries, and squash. This shows the inside of a cache pit from a side view. Photo by Gwyn Herman.

Besides bison hunting, agriculture (farming) was a means of support for both the Mandan and Hidatsa. The women were the farmers. Corn, squash, pumpkins, beans, sunflowers, and tobacco were their main crops. Raising these crops provided food for the families. The crops were also used as trade items to get products from other tribes.

Each earthlodge had a hole in the ground about 3 to 4 feet deep. This was called a cache pit. It was used to store dried corn, nuts, berries and squash. The cache pit acted somewhat like a refrigerator because of the cooler temperatures below the surface of the ground.

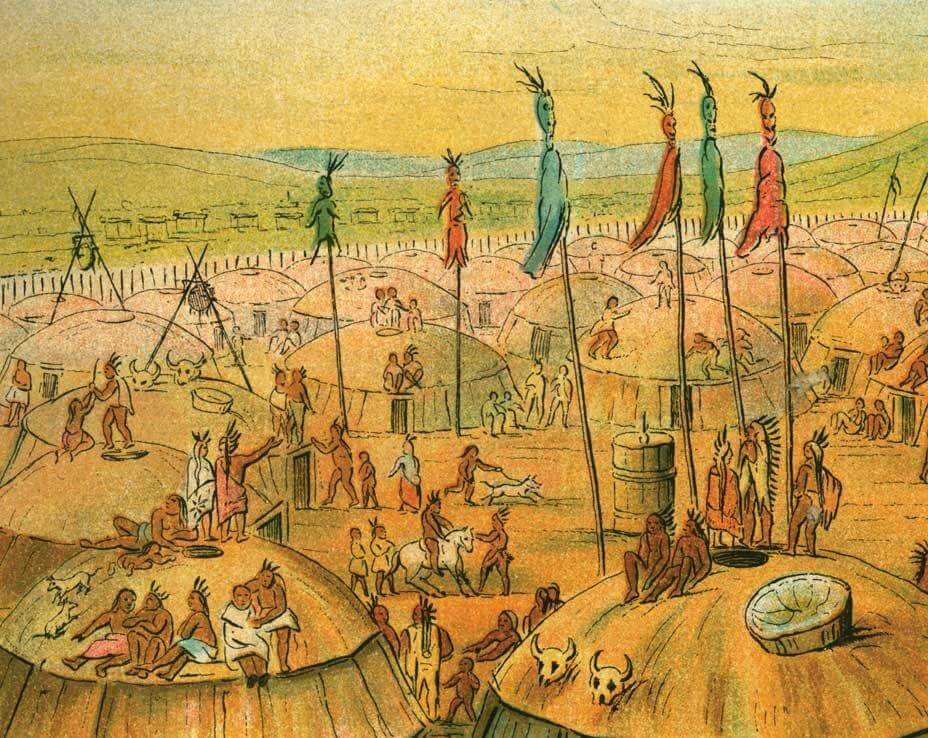

Birds-eye view of a Mandan village. SHSND 970.1C289NL.

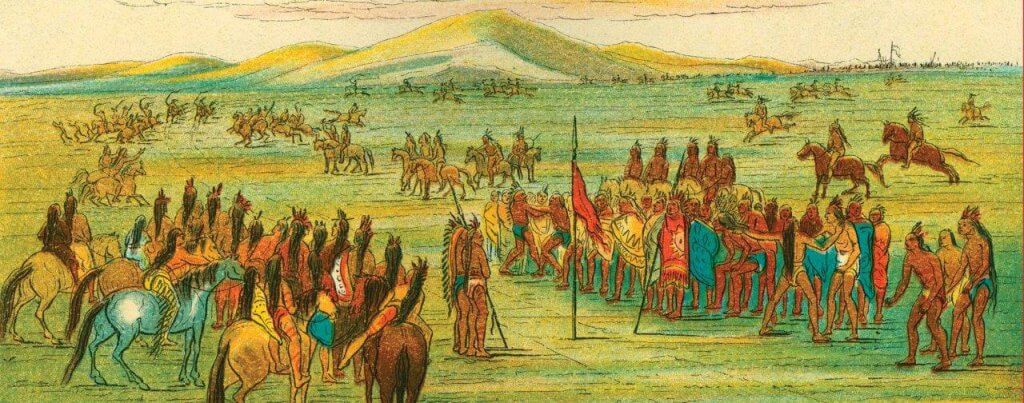

From 20 to 40 earthlodge homes usually made up a village. The villages became major trading centers. Money was not needed in this trading business because a system called “bartering” was used. Bartering means trading items for other items without exchanging money.

Nomadic tribes would come to the villages to get corn and other food products. In turn, the agricultural people would trade for items that the nomadic tribes had gotten by hunting or trading in other places.

During the summers, nearly the entire village would take their tipis and move out onto the plains to hunt bison. The actual hunting would be done by the men, but getting the meat ready for winter use was a job done mostly by the women.

Horses came to the people of this region around 1750, but weren’t important until around 1800. The Mandan and Hidatsa probably obtained their first horses by trade with Indians of other tribes.

The Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara learned that horses made hunting easier. Horses were also important in defending the village. They became important trade items and were often stolen by enemies.

Warriors from one tribe would often raid other tribes in order to take their horses.

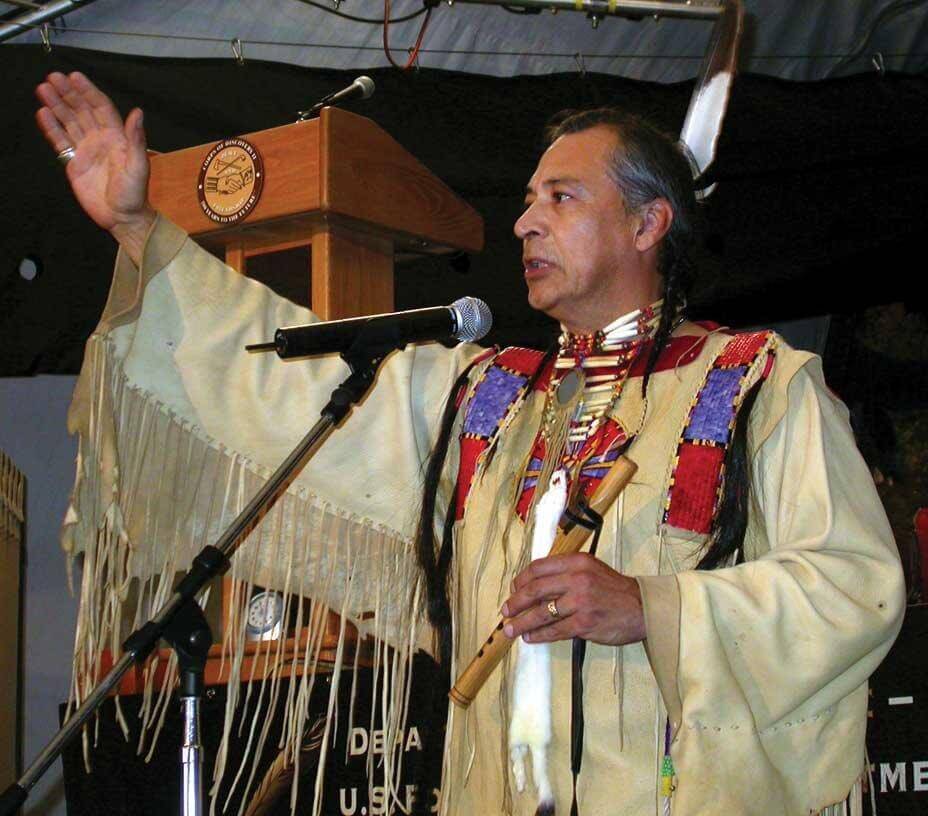

Keith Bear—Three Affiliated Tribes

World renowned flute player, Keith Bear, Hidatsa and Mandan, is from the Three Affiliated Tribes in Fort Berthold ND.

Keith Bear, a member of the Three Affiliated Tribes, is a flute player known all over the world. He uses his flute to tell stories.

Keith started his life being raised by his mother and relatives in the Sioux and Mandan cultures. Before he started first grade, he was placed in a foster home and between the ages of 6 and 12, lived in 14 different non-Indian foster homes.

After Keith grew up, he was working in the Wyoming oil fields. Another worker carved a flute out of wood and gave it to him. Keith carried this flute around for two years before he got interested in playing it. At that time, he had a drinking and drug problem and did not know what he wanted to do with his life.

One day, Keith realized that he wanted to change his life. He took his flute out to a hill and stayed there for three days and three nights while he sobered up for good. As the wind blew through the flute, it made a low tone, and the rustling leaves added to the sound. Keith thought this was a gift from the Creator.

When he came down from the hill, Keith started playing his flute. At first, only sour‐sounding notes came out, but the more he practiced, the better it sounded. After about a week of steady practicing, he played his first song.

Keith’s uncle taught him how to carve his own flutes, and over the years, Keith has made many different kinds, each with its own special sound. He is also a storyteller and sometimes dresses in his regalia when he performs. He has played music with many famous orchestras, including the National Symphony in Washington, D.C.

Keith has proved that even if people have not had the best of childhoods, they can turn their lives around if they want to. Today, Keith Bear is famous, not only in the United States, but also throughout many parts of the world. He has won awards for his music and performances, and he has also acted in a movie. He believes that all humans were created by the same Creator, and everyone has a connection with everyone else. Flute music is the wind that breathes life into the heart.

On-A-Slant village was built about 400 years ago near what is now Mandan, where the Heart runs into the Missouri River. Photo by Gwyn Herman.

About 400 years ago, the Mandan people from some nearby villages got together and built a new village beside the Missouri and Heart Rivers, near the present-day city of Mandan ND. They called this village On-A-Slant because it slanted toward the Heart River. About 75 lodges were located in the village and its population was about 1,000.

In 1738 (about 280 years ago), a French fur-trapper and trader named Pierre La Vérendrye (lah ver-ON-dree) came to North Dakota from Canada. La Vérendrye was among the first non-Indians to set foot in North Dakota. He wrote in a journal about his experiences and so became the first Euro-American to record history in this area.

La Vérendrye spent some time visiting and trading with the Mandan people along the Missouri River. He estimated that their population was about 15,000 and reported that they were very peaceful people.

Some years after La Vérendrye’s visit, other Europeans and Euro-Americans began trading with the people in North Dakota. They brought metal tools, cloth, beads, rifles, kettles and other manufactured goods to trade for garden crops, meat, furs and other items.

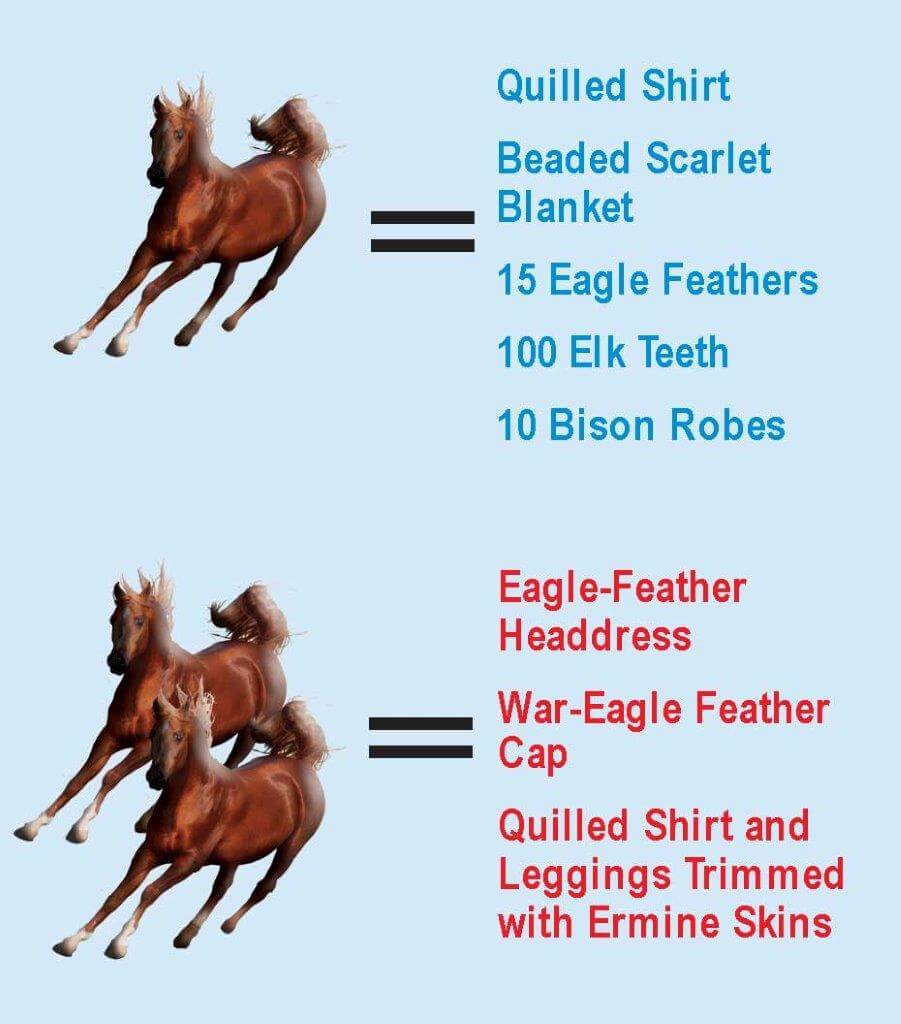

Horses were a big advantage in hunting and war and were valued by the Plains Indians. The horse was also used for trading. This poster shows the items that could be traded for one and two horses. SHSND-ND Studies.

Because the Missouri River was a major travel route, the agricultural villages along the river were an ideal setting for trading. In fact, this area became one of the largest trading centers on the continent. It has been called “The Marketplace of the Central Plains.”

Trade with non-Indians changed the Indians’ way of life in many ways. Spear heads and arrow points could now be made of metal instead of chipped stone; cloth could be used in place of hides to make clothing and blankets; and colored glass beads could be used for decorations on clothing instead of the porcupine quills that had been used before. Trading was done within the villages and forts were also set up as trading posts. Corn, bison hides and beaver pelts were considered very valuable by Europeans and Euro-Americans and commerce became a huge business.

At the same time that commerce was becoming more important, something dreadful happened that had a tragic impact on the Indian people. The natives of North America had never been exposed to deadly diseases that had been in Europe for hundreds of years or more. Therefore, they had no natural immunity from diseases such as smallpox, measles and typhoid fever.

In 1781, a severe smallpox epidemic occurred in the villages. This horrible killer reduced the population of the Mandan Indians from about 12,000 to about 1,500 within a matter of just a few months.

Mandan horse races—the finish line. SHSND 970.1.

On-A-Slant village, which had existed for about 200 years, was almost totally wiped out.

Another village, on the present-day historic site called Double Ditch Indian Village near Bismarck, had been occupied for almost 300 years and when the epidemic struck, most of the residents died.

After the villages were weakened by disease and death, the Lakota attacked. The attacks caused the remaining people to move north, closer to the Hidatsa. The Hidatsa also lost many people to smallpox.

In the 1700s, the Arikara (ah-rick-ah-rah), or Sahnish, people came from the south and settled along the Grand River, a tributary of the Missouri. During the early 1800s, they moved northward along the Missouri River.

When the smallpox epidemic hit, their population was reduced from about 20,000 to only about 4,000. In about 1825, they continued up the Missouri River and settled near the Mandan and Hidatsa villages.

The Mandan and Hidatsa people were somewhat alike in their lifestyles and languages. The Arikara had a very different culture, but they lived in earth lodges in permanent villages. They raised crops and were traders. All three tribes benefitted from this close relationship.

In 1837, a steamboat docked at the Fort Clark trading post near the present-day town of Washburn ND. A man on the boat was sick with smallpox and the illness had spread to others on board. By the time the steamboat reached Fort Clark, it contained several men with smallpox. When Indians came aboard the boat to trade, they were exposed to the illness. Though a warning was sent to other camps and tribes, the disease spread rapidly among the Indian tribes.

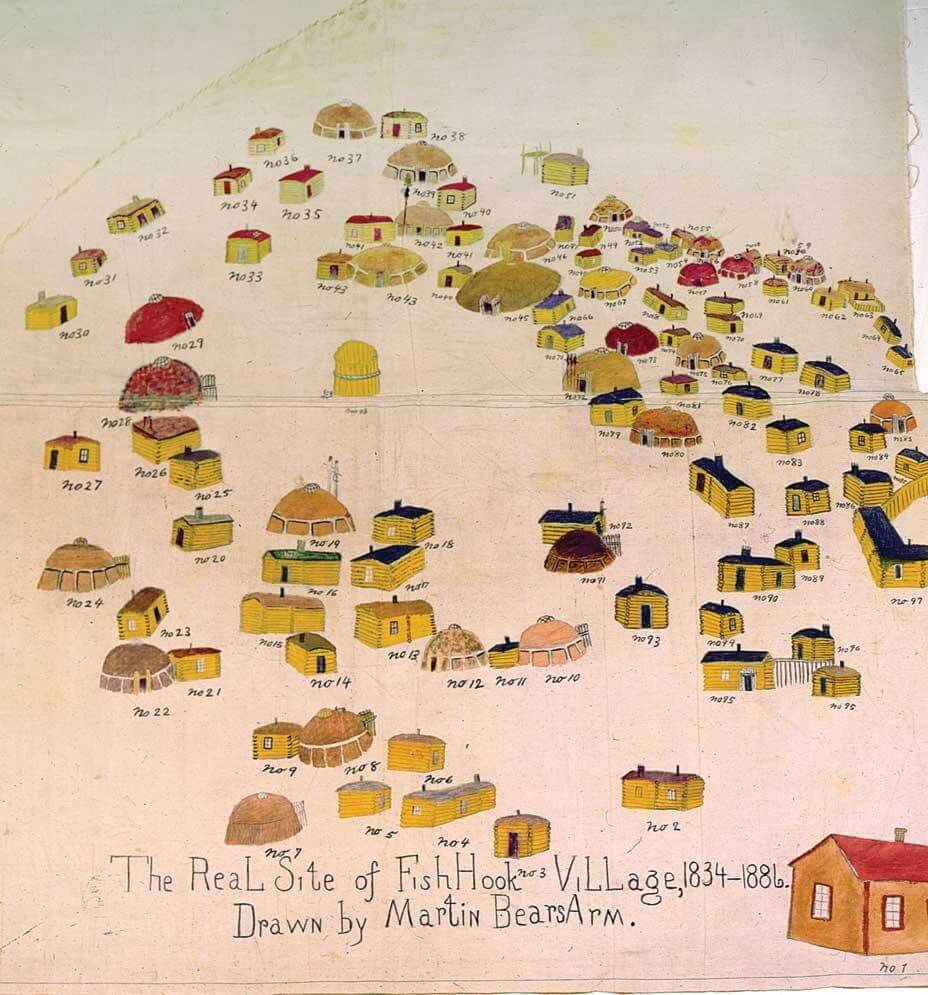

In 1845, the Mandan and Hidatsa people started a village together on the Missouri River north of their old villages. The area of land where they built this town was in a bend of the river that reminded them of a fishhook. They called this village “Like-A-Fishhook.”

In 1862, the Arikara joined them. All three tribes had lost so many people in the epidemics that they felt it was necessary to band together to protect themselves against nomadic tribes that were raiding their villages.

Like-A-Fishook village, named for its location at a sharp bend in the Missouri River, was built by the Mandan and Hidatsa. The drawing is by Martin Bears Arm. SHSND 799.

Entire families as well as entire villages were wiped out by this disaster. The population of the Mandan people was reduced from about 2,500 to only about 125 people. More than half of the Arikara people died, leaving their population at about 1,500. The Hidatsa were also hard-hit.

Smallpox was a disease that affected Europeans for hundreds of years. It came to North America with the colonists. Europeans often died of the disease, but those who recovered became resistant or immune to another infection. American Indians had no immunity.

In the 1820s, an English doctor developed a vaccine for smallpox. The vaccine helped prevent the disease in people who were given the vaccine.

In the 20th century doctors and scientist made a major effort to wipe out smallpox. They were successful. Today smallpox is a disease of the past, and no one can get the disease.

Even though the three agricultural tribes were alike in some ways, they each had their own language, as well as other cultural differences, so each tribe lived in its own section of the village. The Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara groups became known as the Three Affiliated Tribes.

In 1851, a treaty with the U.S. government set aside twelve million acres of land as a reservation for the Three Affiliated Tribes, but the government later took away most of this land, leaving the Tribes with only about a half-million acres.

The Lewis and Clark Expedition visited Black Cat village in 1806.

Plains Nomadic People—followed Bison Herds

After a time, other Late Woodland groups moved into North Dakota. The Plains Nomadic

people probably came from forests in the east. They did not have permanent homes but traveled in small bands following bison herds.

The Plains Nomadic people left traces that show they lived in all parts of North Dakota. They may have been ancestors of the Sioux (soo), or Dakota, Indians. Another Late Woodland group that came from the east may have been ancestors of the Chippewa Indians. The Chippewa continued the lifestyle of the Woodland people.

Evidence has been found that the Woodland and Plains Nomadic people did a lot of trading with other groups. The first metal used by people in this area was copper, probably from Minnesota. It was made into knives, axes, and jewelry.

Seashells from both the Atlantic and Pacific coasts were uncovered at archaeological sites in North Dakota, and Knife River flint has been discovered in sites hundreds of miles from where it

Mary Louise Defender Wilson

Mary Louise Defender Wilson is a storyteller who has become famous throughout the United States among both Indians and non-Indians. She is a member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and also is part Hidatsa.

Mary Louise Defender was born in Shields ND on Oct 14, 1930. Her family raised sheep and gardened.

At a young age, she learned storytelling from her mother, grandparents, and other members of her extended family. She has become famous throughout the United States among both Indians and non-Indians. A member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, she also is part Hidatsa.

They told stories, not only for entertainment, but also to educate both children and adults.

By the age of 11, Mary Louise was already a good storyteller. She could speak three languages—Dakotah, Hidatsa and English.

The stories she had heard from her family and from the elders of her tribe were stored in her memory and she began passing these stories along to other people.

Mary Louise married William Wilson, a Navajo (nav-a-ho) Indian. He introduced her to Navajo elders who also told stories. When she returned to Standing Rock, she asked the Sioux elders to teach her even more stories.

Animals were a big part of many of the tales. They taught lessons about kindness, sharing, helpfulness and other important values.

Today, Mary Louise is an elder in the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. She has been a teacher and has also worked to educate teachers and others about American Indian culture.

She is very wise and uses her wisdom in ways that will help preserve traditions of the Indian people. Her goal is that all people respect each other and respect all life.

Mary Louise has won many awards throughout the United States for her storytelling ability. Many of her tales are now available on CDs and YouTube so that everyone can have a chance to hear the charming voice and the delightful stories of this great person.

From coast to coast, one of the best storytellers in America is Mary Louise Defender Wilson.

Archaeological Sites

An archaeological site is a place where archaeologists find evidence of people who lived long ago. These people did not record their history on paper, so archaeologists look for other signs of their cultures.

Evidence might include stone or bone tools, pottery, burned wood from the hearth (fireplace), shell jewelry or tools, or a burial. Archaeologists might find these things on top of or below the ground. They are careful to treat the objects respectfully.

In the time of pre-history, people reported on events and spread information by talking and telling stories. For the American Indians, storytelling was a ceremony that made the word sacred. The stories had to be told exactly the same way every time.

In this way, information was passed from generation to generation (parents to children, grandchildren, etc.). Passing on information this way is called oral history.

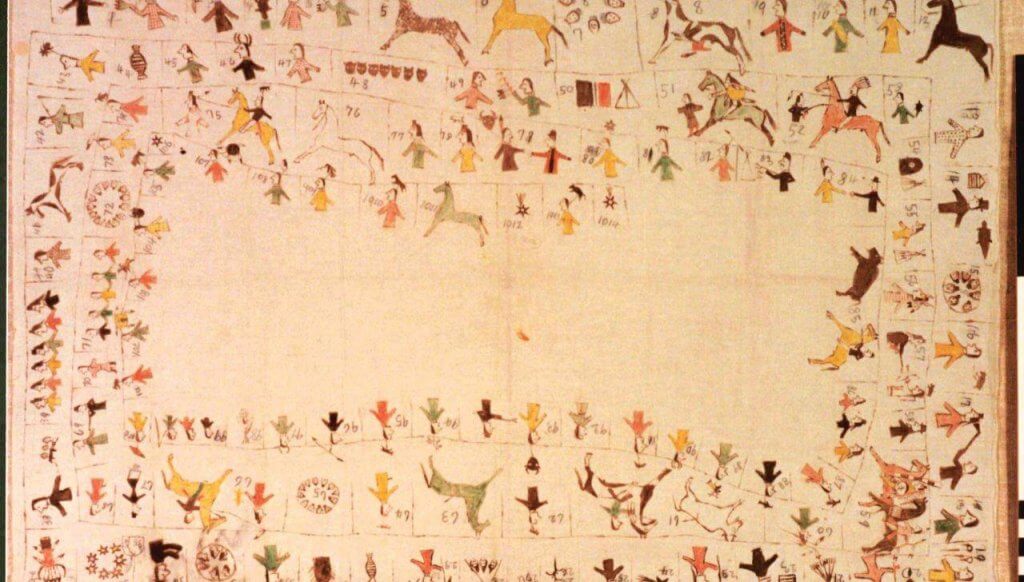

Another way of holding onto memories was by using pictures and other forms of art. Examples are carvings on rocks, pictures on tipis, and “winter counts.” The men did the pictographs, or picture-writing, because they were keepers of the tribe’s history.

Winter counts were calendars and records of history that were made by many of the Plains tribes. Each winter, a special event from that year would be selected. A picture would be painted on an animal hide or piece of cloth. A storyteller would use this as a memory aid to help in telling the story of the tribe’s past. Being the “Keeper of the Winter Count” was an important responsibility.

A winter count might also be called a pictograph. When groups used pictographs and other forms of written language, information could be saved and spread to more people than could be done by the spoken word alone. A written record of past events is called history.

Winter count by Swift Dog. SHSND 674.

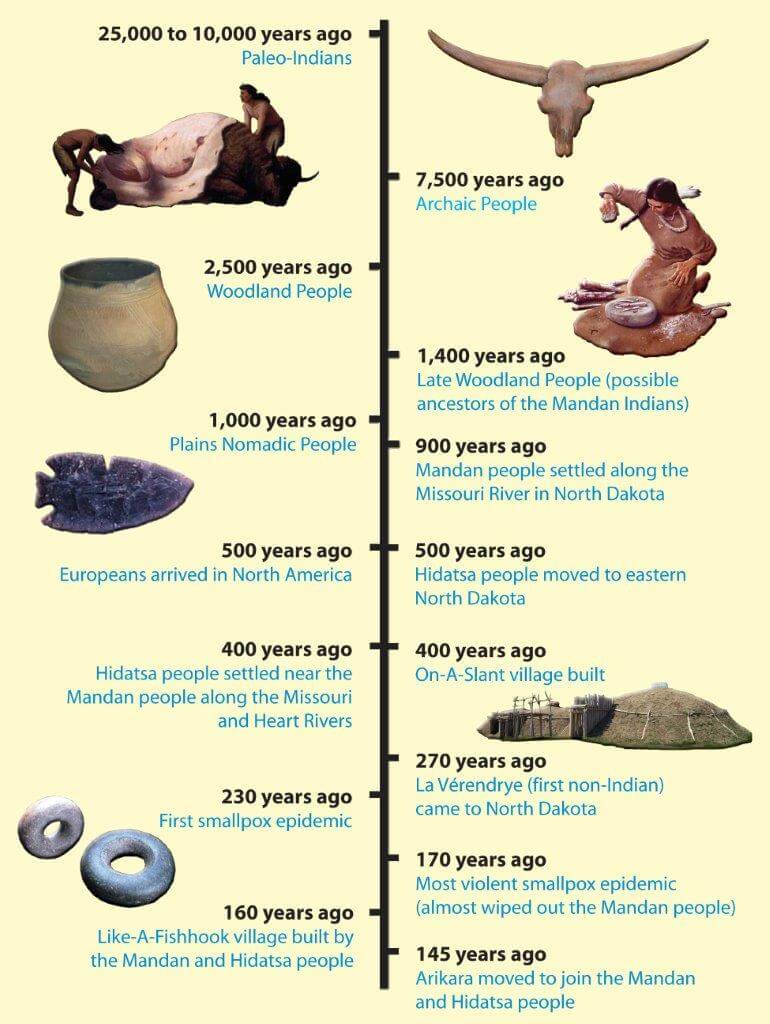

Timeline: American Indians of North Dakota

This timeline shows events from 25,000 years ago through European contact and two ND smallpox epidemics. https://www.ndstudies.gov/gr4/american-indians-north-dakota/part-2-early-history-american-indians-north-dakota/section-4-woodland-people __________________________________________________

________________________________________

NEXT: Part 3—American Indians of North Dakota (4th grade)

________________________________________

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog