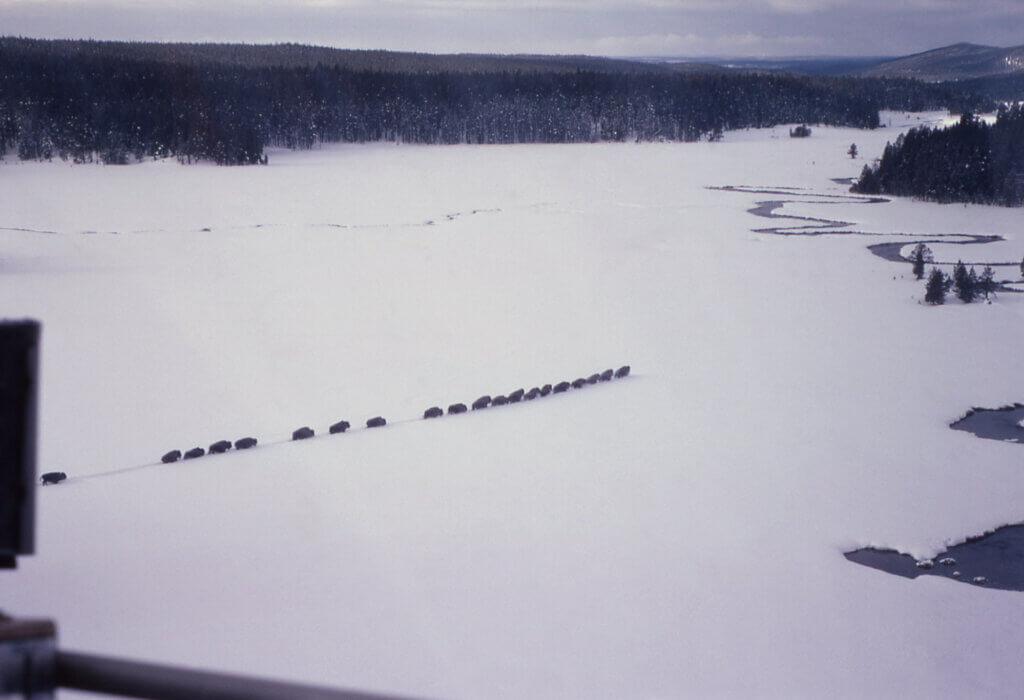

This is the way buffalo make trails. In Yellowstone Park, even when they have lots of room to wander or bunch up, they still prefer to “follow the leader” when they’re headed somewhere. Photo NPS, YP.

There is at least one more Historic Buffalo place that I’ve been wanting to visit in our area of historic Buffalo sites. Or actually two—Buffalo Trails and Buffalo Wallows!

My family has been friends for at least 40 years with ranching families who live north on Cedar Creek. For all those years we’ve been invited to drive up and see their buffalo trails and buffalo wallows.

Was I always too busy to go? I don’t think so—but somehow it just didn’t happen. Besides, I never thought there’d be so many of them.

As their veterinarian, my husband Bert might have seen those historic trails and buffalo wallows, but never described them to me! Now he’s gone—but I had another opportunity.

So now I’ve been there! And they are impressive! Honest to goodness Buffalo Trails trod centuries ago, and Wallows rubbed and scratched (and we’re pretty sure, enjoyed) by generations of migrating Buffalo herds. Dozens—maybe hundreds of them!

When they got wind of our Buffalo Grande mission, Allan and Virginia Earsley, ranchers in the Cedar Creek area, offered a motorized side-by-side ride for Dr. John Joyce and me to that special hill and ravines in their pasture where original buffalo trails show up best in spring.

Earsleys live only a few miles north of Hettinger, in the general area where Cedar Creek crosses under Highway 22 on its way east to the Missouri River.

Now we have photos. We plan to shoot more in fall, too. And maybe some more in early spring, when the grasses are just peeking through.

It does make an impact to actually see these trails, note how many there are! And to re-live what was going on in those days! Probably 7,000 years ago.

Older neighbors and Allan’s grandparents identified the Buffalo Trails before cattle began making their own trails. Early settlers told their families these were NOT cattle trails.

They told stories of trails made by big buffalo herds—had to be wild buffalo, they said! Maybe in the thousands! How else would there have been so many Wallows??

Where’s the Research?

On Apr 20 and May 4, 2021, in Blogs 30 and 31 Ronda Fink and I published our first blogs on Buffalo Trails—in Indiana, where they are called Buffalo Traces.

On Jan 11, 2022), in Blog 49, we wrote another blog—this time about “Buffalo Trails in ND” written by a North Dakota Geologist. Made me wonder where other researchers are looking at these features of the landscape. Turns out they may not even be looking??

Unlike our western trails—which were used by wild buffalo more recently—the Indiana Traces have not been used by buffalo since the early 1800’s.

There, local historians are trying to put the buffalo traces back together, after nearly two centuries of intensive farming, invasions of cities and towns and highway building.

In the forested lands of southern Indiana the traces had become welcome travel lanes, swept bare of trees by great annual Buffalo migrations.

Civilization had moved in and the buffalo that had congregated at the Kentucky salt licks were mostly killed off. Survivors moved on to safer pastures west of the Mississippi.

In some places what was called the Vincennes Buffalo Trace was 12 to 20 feet wide and worn down to a depth of 12 feet, even cutting down through solid rock.

John Bluemle: ND Geologist

John Bluemle worked with the ND Geological Survey for 28 years from 1962, then spent 14 more years as ND State Geologist, from 1990 to 2004.

A North Dakota geologist who wrote about Bison Trails in North Dakota is John P. Bluemle. He was employed by the North Dakota Geological Survey from 1962 and served as ND State Geologist 14 years from 1990 until 2004. Bluemle cited research by Lee Clayton, also a North Dakotan.

Bluemle said he adapted much of his report from an article by Lee Clayton: Bison trails and their Geologic Significance published in the national magazine Geology, Sep 1975.

The trench-like features seen throughout ND from airplanes were initially interpreted as caused by glacial action, with bedrock joints and faults.

They have also been listed as glacial disintegration trenches, a kind of long, narrow depression resulting from the melting of an ice-cored crevasse filling.

However, the disintegration-trench hypothesis was proven wrong when it was pointed out that these trenches are found throughout southwestern North Dakota—well beyond the limit of the last glaciation.

“An unusual kind of landform found in several places in North Dakota was created by once huge herds of bison. The bison trampled shallow grooves across the prairie, forming trails that appear as lines on air photos,” wrote Bluemle.

“These bison trails were first recognized in North Dakota in the 1960s by former University of North Dakota geologist, Lee Clayton.

“The trails are shallow grooves or trenches, generally a few feet deep, several feet wide, and several hundred feet long. Where they cross narrow depressions, the trails sometimes change to low ridges.

“The ridges probably formed as sediment [solid fragmented material such as gravel transported and deposited by wind, water, or ice] tracked downslope by thousands of hooves.

“Bison trails are common throughout the grasslands of the northern plains, and, in fact, many have been misinterpreted as bedrock joints [a brittle area of a large rock body with pressure-induced fractures with the same orientation] or glacial features such as a small washboard ridge that forms from material along the leading edge of a glacier.

“Bison trails are straight or gently curved and they show up on aerial photographs as dark lines,” says Bluemle.

“The trails tend to be parallel to high-relief features such as bluffs and steep slopes, and otherwise they typically trend northwest to southeast, parallel to the prevailing wind directions.”

He writes that the trails were probably formed when large numbers of bison converged on water holes or were funneled along a particular path by the constraints of topography.

Buffalo Trails may be formed when large numbers of bison converge on water holes. Photo courtesy of NPS.

How Can We Find Buffalo Trails and Wallows?

Early homesteaders noted them first and some correctly identified them as buffalo trails and passed that knowledge down to their descendants who still work the land.

So if you’d like to find out where buffalo trails are in your area, start by asking old-timers and listen to what they have to say.

Some local people—ranchers, pilots and people with an interest in history—already know where there are honest-to-goodness buffalo trails.

And there are probably many more just awaiting our discovery.

The big hooves of buffalo dig deep trenches. And in the right kind of soil their feet pick up big chunks of mud, fling them around and build the trails higher causing a ridged portion of thick topsoil. Not fluvial sand and gravel as would be evident if they had been disintegration trenches.

We can find parts of these trails and the wallows in western North Dakota, if we know where to look. And no doubt in other areas too.

There’s still clear evidence of great buffalo herds!

Here are ‘best ways’ to find Buffalo Trails, according to geologists:

- In Spring when the grass is short (or winter days between times of snow cover)

- Throughout the plains and prairies in pasture lands which have not been plowed

- In soft and permeable soil (where rainfall soaks in readily—instead of draining off, which erodes slopes and destroys trails)

- The trails are like trenches, about 3 feet deep—but on steeper slopes may be 9 to 12ft deep. As wide as 6 to 60 ft across—typically 15 to 30 feet. Stretched out in varying lengths depending on soil and terrain—may be as much as ½ mile long

- In some areas trenches show up in combination with higher ridges of topsoil as if clumps of dirt have been kicked up and gobs of mud released after being stuck to hooves

- Where they cross depressions the trenches may be replaced by ridges

- Trails are usually straight or slightly curved

- They may run parallel to prevailing winds—such as on the diagonal from Northwest to Southeast

- May lead around bogs, to water or salty areas

- The trenches tend to cross ridges, small hills and valleys

- They might be identified on hikes, from high points, low-flying airplanes or on Google maps

I assumed that Buffalo Trails and Wallows would be researched many other places—especially in National Forests and BLM Lands (Bureau of Land Management).

Surprisingly though, other states than Indiana/ Kentucky and ND—even here in the western states—seem not to have researched buffalo trails or wallows.

Looking for confirmation, I requested information from state and federal researchers with the Bureau of Land Management and other US departments.

The typical replies I received are similar to this one:

“Good afternoon, Francie. Thanks for sending your inquiry. I checked with others in the office and no one with BLM Colorado has investigated Bison Trails and Buffalo Wallows in any states in the US, or is aware of any BLM work on the topic. Best of luck with your project!”

From Malia Burton, Branch Chief, Lands, Realty & Renewable Energy, BLM Colorado State Office.

Perhaps others will find this an interesting topic for research, before the evidence disappears entirely.

But as Tom Schoeder attests, the Wallows near Cedar Creek are not as clearly defined as when he was a child, even in that undisturbed School Section near his home. And Buffalo Trails maybe even less so . . .

When it’s time to go somewhere special a matriarchal grandmother takes the lead. Like heading down to Cedar Creek to drink. She takes off and the herd follows single file. Photo courtesy of SD Tourism.

Trekking down to water in the Cedar Creek, day after day. Cutting deep narrow grooves in the hills as they apparently went single file—with a matriarch cow leading, just as buffalo tend to do today when the herd is headed somewhere—such as to water.

Down the hill they went—single file–then back up onto the grassy plateau where the herd spread out to graze again

In another season and yet another, they returned to follow the same trails—ancient trails that seemed to cut across new fences the newcomers built.

I wanted to take that ride to see the trails. Could hardly wait till spring when grass began to green up and reveal these mysterious trails. Known first to original settlers who refused to plow them up—and passed their stories on to grandkids—although unfortunately they didn’t write them down.

Yet we can still see and document these historic buffalo trails!

Dr John Joyce finds the now-grass-filled trail where buffalo went down to water. Apparently these were buffalo trails where they went down single file to the Cedar Creek to drink, then turned around and walked back up onto grassy plateaus to the south to graze.Across the creek to the north, other trails came down to the Cedar—and returned after watering. Can you Find Buffalo Trails where You Live? Photos FMB

Young bulls jockeying for the leadership position across a pasture near the Slim Buttes. Some of the old single-file trails are still here, having cut deep grooves into the landscape. Photo FMB.

Buffalo Wallows

A mighty bison bull wallowing in the dust in Yellowstone Park in 1877. Photo NPS, J Schmidt.

Back up on the plateau where the grazing is good the herd would have scattered to fill their bellies.

One hundred and 50 years ago after a quenching drink it may be that many individuals sought a nice comfortable wallow.

The wallowing evidence is here as well. There’s a School Section—which has never been plowed and is now divided into 4 pastures for rotational grazing of cattle—with many old buffalo wallows.

Tom Schoeder took Connie Messner and me on another “side by side” vehicle to see the wallows in that school section.

They tend to be almost round—perhaps 9 to 10 feet in diameter and perhaps as much as 2 ft in depth. And there are lots of them, nearly all filled now with grass, but clearly noticable. Perhaps made by thousands of buffalo during their many migrations.

In clay areas, the wallows may have held up longer. Tom Schoeder told Connie Messner and me that his family called the depressions “knolls,” perhaps because they tend to be found on higher ground. There were many, perhaps 60 or more in that one quarter-section. Wonder how many buffalo that represents? Thousands? Photos by FMB.

In her report of the Buffalo Wallows Conni Messner wrote, “On the evening of 13 July Francie and I drove to meet Tom Schoeder northwest of Hettinger to look at the buffalo wallows that were still visible on land that was owned by his grandfather since 1907.

“Driving west on Hwy 12 and north on Hwy 22, we met Tom not far from the turn on 18th Ave. He led us to a section of land that is being used for grazing but since it is ‘School Land’ it has not been used for agriculture.

“We jumped onto his 4 by 4 and drove to many sites that Tom remembered his grandfather telling were made by buffalo rutting in the dirt.

“We must have seen approximately 50 depressions. Some of these wallows were on flat land and some were up on what he called the knolls—or ridge line. Tom said the Wallows were more visible when he was a child.

“Cedar Creek was flowing and he related that the buffalo would drink here before heading south to their grazing area. As the buffalo returned, they would go single file so there are supposed to be ‘trails’ that can still be seen but difficult to find right now due to the vegetation.

“Tom was very clear in the fact that he was not an expert on this history and this information he was sharing with us was from his childhood memories.

“He also stressed that this land is Our Land owned by the State of North Dakota and can be visited without permission.

“Other than dealing with the mosquito population and the hard-to-close-gate we had a very pleasant evening.”

Thanks Conni for sharing our Wallow experience with the Bufalo Grande group! I regret not going up there long ago, when invited to see this by Tom’s parents—only a few miles away. I never realized there would be so many visible trails and wallows up there along the Cedar Creek!

I had expected maybe 1 trail—and 1 or 2 buffalo wallows at the most.

As it is, there must have been something like perhaps a thousand buffalo grazing there at once. Why else would they need so many wallows!

We estimated perhaps 60 or more wallows in a single pasture (which was ¼th of a section, or 160 acres). They seem to be clustered more heavily together along somewhat higher land than down on the Cedar Creek itself, where the single-file trails came down to water.

Tom tells us his family called the wallows “knolls,” evidently to recognize their placement on higher ground.

Jim Strand, local Buffalo Herdsman of the Blair Johnson herd in SD, tells us that when flies are bad, or it’s hot, his buffalo will seek higher ground where they can catch a breeze.

For a wallow they like sandy soil and will throw dirt and dust up over their backs. If a wallow happens to contain rainwater—well, splashing mud around and onto their own hides makes it even better!

Now our Buffalo Grande group has done it. We took photos of the buffalo trails and the wallows.

And we heard the remembered words from hardy pioneers who saw them first—and recognized the trails and wallows as ancient evidence—where likely thousands of buffalo once tramped the ground and thrived.

These majestic trails and wallows are one more link in our Buffalo Legacy. They fit in perfectly with the Historic Buffalo sites we celebrate in our Hettinger/Lemmon/Bison/Buffalo area.

So whether your family has been here 7,000 years or just a few—if you’ve put down roots in this community, this is your Legacy—yours and mine! It’s a Buffalo legacy of which we can all be proud.

Sources

Berg, Francie M, Apr 20/May 4, 2021 Blog 30 & 31: BuffaloTrailsandTales.com. “Buffalo Traces, Part 1 & Part 2.”

Berg, Francie M, Jan 14, 2022, Blog 49: BuffaloTrailsandTales.com. “Can you Find Buffalo Trails where You Live?””

Clayton, Lee, 1970b, “Bison trails and their geologic significance,” Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs, v. 2, p. 381.

Clayton, Lee, 1975, “Bison trails and their geologic significance,” Geology, p.498 – 500.

_________________________________________________________________

NEXT: ALBERTA 4-H BISON PROJECT

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog

Francie, I so enjoy reading your blog. I am learning so much about the history and restoration of the buffalo on the Great Plains.

Thank You.

Glad to hear from you, Chuck! This is fun. Seems like there’s always more to learn about the Magnificent Buffalo! (As Wm Hornaday dubbed them way back in 1887, when he predicted their Extinction.)

Thanks, Francie