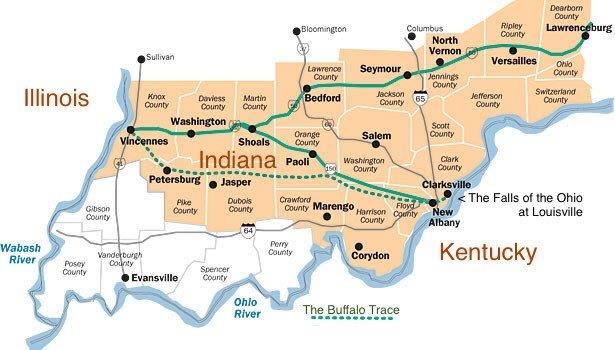

US Hwy 150 follows the Vincenne Buffalo Trace across southern Indiana from the falls of the Ohio River on the east. Historic pathways.org.

Bison east of the Mississippi have mostly disappeared from American memory. Yet, up until the Revolutionary War, buffalo could be found from New York to Florida and from the Mississippi River to the tide-water lands of the east coast.

They left their mark in Indiana and Kentucky in deep, hard-packed trails—called Buffalo Traces.

Various trails also converged around the major salt licks, probably near present-day Lick Fork and French Lick in Indiana.

Buffalo only arrived east of the Mississippi River about the time of European discovery of America in 1492, according to Indiana historian David Ruckman, a retired surveyor and author who is helping to locate the Trace. They vanished from Indiana by 1810 –“along with most of Indiana’s Native American families and the remnants of their proud tribes.”

The mineral springs of the valley, now famous for their high sulfur content, also contained high natural levels of salt.

As the spring water spread over the rocks and ground surrounding them, the water evaporated and left the salt behind.

An Englishman first reported bison near the Potomac River in 1612.

Until they were hunted to extinction by white settlers, buffalo were widespread and in places regionally abundant, leaving lasting impressions on the eastern landscape.

When the French and British colonists first came into what is now southern Indiana in the 1700s, thousands of bison were traveling in their annual fall migrations through the wilderness from the grasslands of the Great Plains across the Falls of the Ohio River, then south into Kentucky.

What an area of the Buffalo Trace looks like today. The Springs Valley Trail System follows the route of the Buffalo Trace for part of its length. If you look carefully, you may be able to visualize the long abandoned trace that played such an important part in one state’s history.

In 1732 the French founded a trading post near the Buffalo Trace’s Wabash River crossing. It later grew into the town of Vincennes in Indiana.

In 1769, Daniel Boone related seeing thousands of buffalo on the western Kentucky bluegrass. Such big numbers came together primarily at mineral licks that attracted bison from all directions, as could be seen by many radiating trails.

Also in 1769, George Washington killed bison in the Kanawha Valley of West Virginia. At this time bison were rather plentiful in the Ohio River Valley.

In a 1787 diary entry, Gen. Josiah Harmar, marching from Vincennes to the Falls of the Ohio, passed through the valley and reported, “A Great Quantity of Buffalo at this Lick.”

In 1792, Moravian missionary John Heckewelder was in a group that camped in the valley for the night, and he wrote of a “Salt spot, several acres in size” littered with animal bones.

Early residents of the area told tales of the bellows of buffalo bulls reverberating in the hills during the rut season.

Buffalo wallow: The mud holes were large buffalo wallows close to White Oak Springs, present day Petersburg. Historic writings mention groups staying near “the mudhole,” and speak of all the paths that radiated out from the wallows and how easy it was to get lost when you left to continue down the trace. They remarked that the woods around the area were quite bare. Many heads and skeletons of buffalo were to be found where they had been shot or died. Buffalo often wallowed in muddy areas to coat their fur with a protective layer of mud to keep off flies and other insects. This site is located on private land with no public access. Photo courtesy of US Geological Survey.

In Indiana the Vincennes Trace’s main line split into several smaller trails that converged northeast of Jasper, near several large ponds, or mud holes, where hundreds of bull buffalo took their turns at wallowing, especially in breeding season—July and August.

Over the centuries the large heavy buffalo created a broad trail through the timbered country.

After a major crossing at the Wabash River going west, the Trace split into separate trails that led across Illinois to the Mississippi River or went north toward what would become Chicago.

The Trace crossed the White River at several points, including near the present-day towns of Petersburg and Portersville, Indiana.

In Chicago, the Trace is called Vincennes Avenue, and after state-funded improvements and straightening, parts became State Street.

Huge herds of buffalo summered on the Illinois prairie and wintered in Kentucky.

The Buffalo Traces were also often “depressed below the original surface, with here and there a knob remaining to shew its former elevation.”

This buffalo migration route was well known and used by early American Indians traveling between the Great Lakes and Tennessee.

Buffalo are good swimmers, but their known crossings were often in the shallowest parts of rivers, as it was in crossing the Ohio at its falls into Indiana from Kentucky. ApogeePhoto.com.

Buffalo are strong swimmers. Yet their known river crossings were often in the shallowest parts of the rivers. That was the case in the buffalo crossing of the Ohio River from Kentucky into Indiana.

In the fall when late calves are still quite young, they might have difficulty swimming alongside their mothers.

Another difficulty was when ice began breaking up. Big chunks of ice interfered with the swimming buffalo and many drowned, so finding shallow crossings were important to the big herds.

Buffalo—’New Kids on the Block’

Buffalo didn’t discover the delights of these eastern states early—as they spread across the Great Plains of America and Canada. But when they did, they made their mark.

Bison appear to have been less abundant east of the Appalachian Mountains and rare within the forested mountains.

According to one Indiana historian David Ruckman, a retired surveyor and author who is helping to locate the Trace, buffalo were “The new kids on the block.”

Buffalo only arrived east of the Mississippi River about the time of European discovery of America in 1492, and had vanished from Indiana by 1810 –“along with most of Indiana’s Native American families and the remnants of their proud tribes,” writes Ruckman.

During the buffalo’s 300 or so years of travel from the Great Plains through Indiana, they left their pathways, he says.

“The Buffalo herds and the ever-trailing packs of panthers and wolves followed parts of existing footpaths, and then by necessity carved their own footpaths, not only through the eight southern Indiana counties, from Clark to Knox, but throughout other parts of Indiana as evidence and legend tells.”

Early travelers along the Buffalo Trace described the thousands of buffalo enjoying the salt licks and grazing the thick underbrush of the cane-breaks in Kentucky.

The mineral springs of the area, now famous for their high sulfur content, also contained high natural levels of salt. As the spring water spread over the rocks and ground surrounding them, the water evaporated and left the salt behind.

George Wilson, an early historian, wrote, “Those who traveled the Traces, in turn, were the buffalo, the Indians, ‘le coureur de bois’ priests, French salt hunters, pioneers, soldiers, settlers, governors, and mail carriers trod these tried and true routes.”

The Buffalo Trace across southern Indiana was followed by all these individuals and groups from earliest times. The Traces made it much easier for pioneers to travel through forests with their wagons.

Often dangerous too. The British incited Indian tribes, who hunted there, to make war on Americans who ventured into what was first called the Northwest Territory of Quebec.

Traveling the Trace

Used for hundreds of years by the Indians, the Trace was likely familiar to the French, who probably visited mineral licks along its route.

Known as the Buffalo or Vincennes Trace, the travel-way was known as durable as any road built today. Early pioneers used the Trace to cross the state and modern roads have been built along portions of its route.

As the colonists took control of the Illinois country during the Revolutionary War, the Trace became a busy overland route. This made it a target for Indian war parties, who were often armed by their allies, the British.

Early settlers and military men remarked on the importance of traveling on the Buffalo Traces. They could follow well-trod roads through the densest forests.

Later European traders and American settlers learned of the Vincennes Trace, and many used it as an early land route to travel west for settlement into Indiana and Illinois. It is considered the most important of the Buffalo Traces into Illinois.

Early settlers and military men remarked on the importance of traveling on the Buffalo Traces. They could follow well-trod roads through the densest forests.

George Rogers Clark was an American surveyor, soldier, and militia officer who joined other colonists from Virginia to claim new land in Kentucky. In 1786, Clark marched 1,000 militia men to Fort Sackville at Vincennes over the Buffalo Trace.

With the Revolutionary War, as the highest-ranking American officer on the northwestern frontier, he organized armies of men and led them several times on the Vincennes Buffalo Trace.

At the time the region was part of the British Province of Quebec, which spanned all or large parts of six U.S. states (Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and the northeastern part of Minnesota).

General George Rogers Clark’s strategy of collecting strong intelligence on the local defenses, followed by a surprise attack in winter were critical in catching the British leader and his men at Vincennes unaware and vulnerable.

He is best known for his captures of Vincennes and Kaskaskia during the Illinois Campaign.

After the war, in the late 1780s, the US government granted land in New York, Ohio and Indiana to veterans as payment for service. George Rogers Clark and his men were granted “many acres of land,” which became known as Clark’s Grant.

Some historians credit Clark with nearly doubling the size of the original 13 colonies when he seized control of Illinois lands from the British during the war.

Clark’s Illinois campaign—particularly the surprise march to Vincennes—was greatly celebrated and romanticized. He became known as the “Conqueror of the Old Northwest,” capturing territory in remarkable victories that helped America expand its borders.

After that campaign, he again followed the Buffalo Trace to return to the Clarksville area. There Clark, who was at one time the largest landholder in the Northwest Territory, was left with only a small plot of land.

Unfortunately, Clark went deeply in debt to finance his troops—outfitting and feeding them— expecting the Virginia officials to reimburse him for his military expenses. They did, but not until several years after his death, when the state granted his estate $30,000 as a partial payment on the debts it owed him (said to have a value of $677,912 today).

Buffalo Disapppeared East of Mississippi

At its most, there probably were about 2 to 4 million bison east of the Mississippi River, historians say.

By the year 1800, bison had mostly disappeared from east of the Mississippi River. Settlers filled the lands known as the Northwest Territory—the area around the Great Lakes and farther south. Urban sprawl began covering up most of their pathways.

The extinction of bison began in east Virginia tidelands by 1730, and proceeded westward as more people settled the frontier.

By the 1770s bison were gone from most or all of North and South Carolina, Alabama and Florida.

The last buffalo were seen in Illinois and Ohio in 1808, and Indiana as late as 1830. The last of the wild bison were seen in Kentucky around 1800.

Other terminal dates for buffalo are given as Georgia in the early 1800s, Pennsylvania 1801, Louisiana 1803, Illinois and Ohio 1808, Tennessee 1823, West Virginia 1825 and Wisconsin 1832.

Burying Buffalo Traces with Roads

Today, the Buffalo Trace is fading into obscurity. The line is left off of most modern maps. And on the ground, there are fewer places each year where the trace can still be followed.

The ‘Buffalo Path’ was known by various names, including Buffalo Trace, Louisville Trace, Clarksville Trace, and Old Indian Road. After being improved as a turnpike, the New Albany-Paoli Pike, among others.

The Trace’s continuous use encouraged improvements over the years, including paving and roadside development. Intensive settlement began to obscure the Pathways themselves.

Layers of civilization now cover the soil above nearly every Buffalo Trace. They have been buried by acres of corn fields, suburban sprawl and traffic snarls.

Still, though it’s rare, the careful observer may find an ancient rut made by the buffalo. Today, local historians and researchers are trying to piece those ruts and the Buffalo Traces together.

Historians have been alert too—surveying the ancient routes from historic documents, establishing parks along the way and placing signs at the Buffalo Licks.

Today, US Route 150 between Vincennes and Louisville, Kentucky, follows a portion of this path.

Sections of the improved Trace have been designated as part of a National Scenic Byway that crosses southern Indiana.

Lost and Forgotten Roads Being Searched

President Thomas Jefferson inspired an army of young men to go to Surveying School in the early days of 1805 to 1807, then sent them out to the Indiana frontier with William Rector and Crew and the mission of surveying the landscape into “thousands of square 160-acre farms, with north-south and east-west lines.”

They marked every half mile with wood posts and dirt mounds and also provided Surveyor’s notes and writings that explained where they intersected with the Vincennes Trace—”the path of the buffalo.”

David Ruckman says it is the notes these young surveyors made long ago that he and other surveyors are now relying on to find and understand the length and breadth of the Buffalo Trace and the various routes that it took.

It was not a single route, but in places multiple trails—sometimes local conditions such as certain years of flooding that may have changed routes.

In December 2014 a group of interested Hoosiers called the Buffalo Trace Working Group group—22 to 30 volunteers—began searching for and documenting the remnants of Indiana’s oldest trail, known as the Vincennes Buffalo Trace.

Today, a group of dedicated volunteers are researching this vital piece of Indiana history—the Buffalo Traces across southern Indiana. Photo courtesy of US Forest Service.

The group first met after Angie Doyle, the heritage program manager and tribal liaison with the Hoosier National Forest, wrote an article about the Buffalo Traces that appeared in The Times-Mail.

Almost immediately Doyle was inundated with phone calls and emails from people, many of whom knew where a segment of the Buffalo Trace was located.

“I’ve been trying to identify segments of the Trace for many years,” Doyle said. “I thought, I’m going to put all of these people together and introduce them to each other.”

An enthusiastic group of 22 volunteers began meeting monthly. They formed committees and

began working toward locating portions of the Buffalo Trace.

On one occasion the whole group—county surveyors, former surveyors, archeologists, research scientists, U.S. Forest Service workers and others—spent a day in French Lick walking along a creek in an area south of the town where the Trace may have been and learning about that Buffalo Trace.

The group shared information they had discovered about the Buffalo Trace, showing maps from the early 1800s that had a road that followed the old bison trail across southern Indiana, with smaller trails that led to the salt licks and springs near where French Lick now stands.

The group developed a mission statement to research, locate and preserve the location and historical significance of the Buffalo Trace in southern Indiana.

Working groups were established to reach these goals:

- Use historical records to determine the location for the primary trail from the Ohio River at Clarksville to the Wabash River in Vincennes.

- Physically locate the remaining remnants of the Trace in all the counties, which include Clark, Floyd, Harrision, Crawford, Orange, Dubois, Pike and Knox.

- Preserve the historical information and document its significance by publishing a brochure and developing other resources that will educate the public about the Buffalo Trace.

- Produce a final document compiling all that the group has learned—in time to have it be part of Indiana’s bicentennial celebration in 2016. This could include putting up signs, developing a website and planning special events, such as re-enacting early surveys.

The volunteer group agreed to track their hours of work as they move forward, Doyle said.

One of the goals for Ruckman is to use GPS, notes and photographs to create a path that can be used to make a 3-D flyover in Google Earth. He said this could be viewed by anyone interested in the Buffalo Trace.

NEXT: Such as “Part 2” of the Traces

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog

Hi, your articles are very interesting. I am Dr. Mike Stone, veterinarian in Minn. Are you any relation to or acquaintance of a Dr. Bert Berg. I believe he was a year ahead of me at U. of Mn. I have been raising bison since 1990 at a small farm here in Mn. Have always been very fascinating with such an intelligent animal. Keep up the writings. I will sign in. Thanks

Good to hear from you, Mike. Yes, my husband was Bert—a veterinarian in Hettinger ND for 35 years, with several buffalo herds in his North and South Dakota practice.

And yes, I too, think Buffalo are very intelligent. Do you think it’s because they are basically wild animals–alert and aware? A poultry expert tells me that wild geese are much smarter than tame geese–and he has raised some of each.

Best wishes, Francie

Since I began reading this blog about a year ago, I have become much more aware of the plight and history of buffalo in North America. The author, Francie Berg, has brought the history of buffalo to the forefront with her knowledge, research and many fascinating and captivating stories that she has shared. I wish I had had access to this information when I was teaching. The manner in which the history of the buffalo is presented would have delighted my students. I am looking forward to my next road trip when I can go and visit some of the sites with my new found information.

Thank you Carol! So glad you think this is valuable info for teachers–especially when they’re teaching Native American culture! They don’t always have time to read widely on any one subject while they’re in the midst of teaching. Have fun on your next road trip across Canada and the US–hope you see some buffalo!

Best wishes, Francie

As a child growing up in south eastern Ind.,Aurora., it would have been heaven to have learned this in school. At that time, 50’s and 60’s, kids did a lot of exploring. There were things to explore all around Southern Ind., Ohio, an KY. That kind of information could have life changing results, as for as what one would have chosen to do with their life. It would have opened up a whole new world for me. Thank you for your hard work an the new found imformation.

Hi Nyeatia

Your home state of Indiana has a wonderful history of buffalo migrations!! Of which I also was unaware when I first ran across that early News Release.

It did take some digging to get the rest of the story–and the interesting photos, but I’m glad you think it was worthwhile. And not just for Indiana kids, but all the rest of us interested in these magnificent animals.

Be sure to check in here again–because in one of the next blogs I’ll explain just what Southern Indiana students are learning about these newly discovered facts on the Buffalo Trace. And I do hope it’s reaching many more students and others throughout Indiana and nearby states–and why not from the Atlantic to the Pacific?

To me this is a cool part of the entire buffalo story which I’ve found is so often buried like the Indiana Traces beneath the dusts of time and the clutter of intense civilization–yet can still be found if we are patient enough to explore the various threads and stories.

Best Wishes, Francie