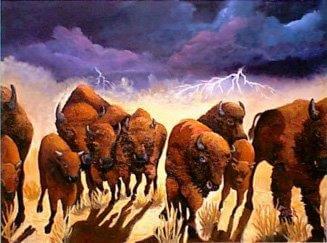

Once wild Buffalo started to run, they tended to stampede faster and faster, trying to stay ahead of the sharp horns pressing from behind. Photo courtesy of SDTourism.

Buffalo stampedes terrified people travelling across the plains.

Stampedes were often described by hunters, soldiers and early settlers on the plains and prairies. No one wanted to get caught in the midst of one without a way to escape—the stampede could be terrible in its consequences.

It took only a small trigger at times to start a buffalo stampede. The yipping of a prairie dog, the cry of a wolf or coyote, a flash of lightening, or a clap of thunder could set it off.

Sometimes it took just one buffalo snorting and starting to run on her own, for others to join in a chain reaction. In seconds a peaceful herd of grazing buffalo could become a charging mass that ran hard for 10 or 20 miles.

Once running, the buffalo herd trampled everything in their path, including other buffalo too slow to keep ahead of the mass. They could not be turned. Or they would turn abruptly at some obstruction.

In April 1846 George Andrew Gordon was out hunting with four friends on the plains of northwestern Texas.

Gordon became separated from the others and in trying to find them, he lost all but one of his rifle bullets. To see better, he began to ride his horse to the top of a nearby hill.

Suddenly he heard a low murmuring sound “as of the wind in the tops of pine trees.”

The sound increased and became a deafening roar. The ground shook and he said his horse shook with fear. But the only place of safety seemed to be a small grove of trees at the top of the hill.

A moment later he saw the buffalo coming and kicked his horse into a gallop.

The trees were about a foot in diameter and free of undergrowth. Only one tree had branches low enough for him to reach.

Gordon stood up in the saddle and grabbed a branch, pulling himself and his heavy rifle up into the tree.

The rushing buffalo were almost upon him, when they apparently heard or smelled his terrified horse, and tried to turn or stop, but slid and fell in a heap.

“In the twinkling of an eye,” he recalled later, “they were overwhelmed by the pressure behind. I have never seen two railroad trains come together, but one who has seen the cars piled up after a wreck can imagine how the buffalo were heaped up in an immense pile by the pressure from behind.”

A small trigger could start a buffalo stampede. The yipping of a prairie dog, the cry of a wolf or coyote, a flash of lightening, or a clap of thunder could set it off.

The buffalo in the rear kept coming at a gallop, but as they reached the heap of trampled and dying buffalo just in front of the horse and man, they dodged to one side or the other.

He watched from his perch on the tree, while his horse stood there against the tree shaking with fear.

“I could now enjoy a spectacle which I fancied neither white man nor Indian had ever before seen. The front rank as they passed was as straight as a regiment of soldiers on dress parade. The regularity of their movements was admirable.

“It appeared as though they had been trained to keep step. If one had slackened in the least his speed, he would have been run over.”

It took nearly an hour of “alternate terror and pleasure,” as Gordon described it, for the entire herd to pass out of the small grove of trees, as he clung tightly to his branch.

He sat there a few minutes after they’d gone, wondering if he’d had a bad dream. Then he climbed down from the tree and took up the reins of his horse, who was still standing there shaking. (Told by (Ital) David A. Dary, The Buffalo Book: The Full Saga of the American Animal, 1974.)

Sharing the Expertise of Buffalo Jones

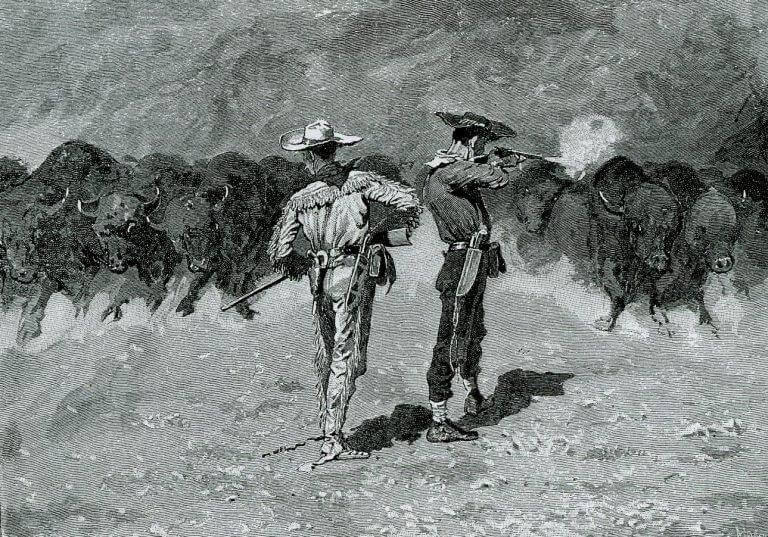

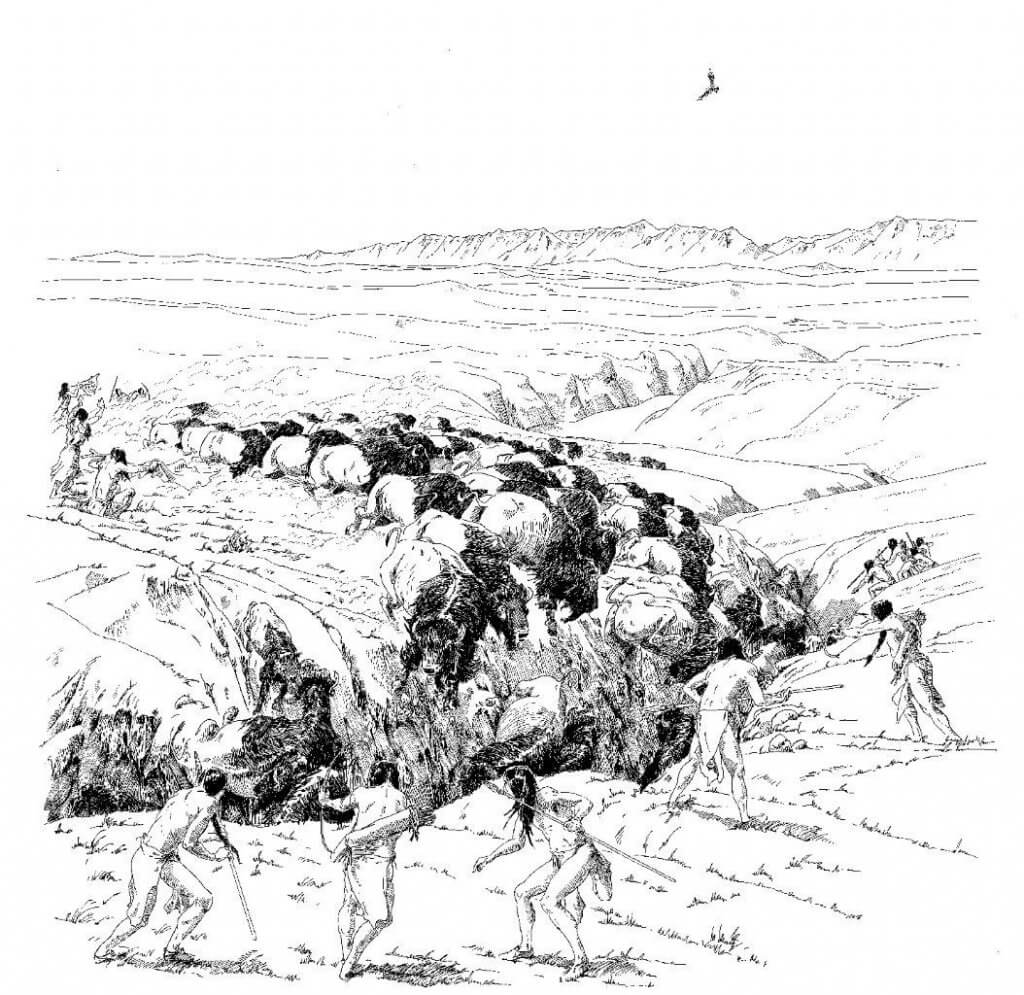

This drawing depicts Theodore Roosevelt’s account of a Texas hunt in 1877 by his brother Elliot and his cousin John, who were caught on the Staked Plains by a buffalo stampede. Their only chance was to split the herd, which they did by shooting continuously into the charging mass. Credit Frederic Remington.

Buffalo Jones describes a stampede and how he coped with it, in his book Buffalo Jones’ 40 Years of Adventure

“During the third of a lifetime spent on the Great Plains of the interior of the continent, I have witnessed many stampedes of buffalo, wild horses and Texas cattle.

“Twenty-five years ago a stampede of buffalo—which then roamed in vast herds numbering millions—was an everyday affair.

“What caused the huge, shaggy monsters, accustomed to the tornado, the vivid lightning, the terrible hail that frequently accompanies the sudden, short storms of the prairies, the wolves and the thousand-and one strange phenomena of nature to stampede at apparently nothing is one of those problems that will admit of no solution.

“Sometimes it was a flash of lightning from a dark cloud. Again, a cry of a starved wolf, the appearance on the horizon of a single figure, a meteor, or perhaps something as insignificant as the barking of a prairie dog sitting on the edge of its burrow.

“If a single animal snorted and started to run, if only a rod, all others near it would start in an opposite direction from it and thus others were frightened until all were a surging mass.

“A herd once started, I have seen the whole prairie for miles absolutely black with the fleeing beasts.

“There was nothing so indescribably grand, yet so awful in its results. The earth, shaken by the heavy tramp of their hoofs upon the hard ground, fairly reverberated as they passed a given point.

“Woe to him, her, them or it that stood in the way of the mighty throng of infuriated, maddened animals!

“Nothing but annihilation, absolute and complete, their portion.

“A buffalo stampede, indeed! How few there are today who have ever passed through this thrilling experience; this moment when the heart fluttered at the roots of the tongue. When the pursuer, revolver or gun in hand, the spurs rolling on the sides of his frightened steed, endeavored to force him nearer to the most horrid of all beasts to the eye of a horse.

“Still on and on, like a cyclone in its fury went the great mass, the living cataract, plunging up as well as down the hills and over the plains, tearing and cutting every vestige of vegetation. And woe unto any and all living creatures that chanced to be in its pathway!

“Often have I heard the heavy rumble as if a terrific peal of thunder were reverberating in the distance. I could see a great cloud without water.

“I could feel my blood run cold and my hair stand on end, as I knew that the sound was not thunder, but the roar of the beating hoofs of a living avalanche.

“I knew the cloud which was approaching nearer and nearer was not rain, but dust and dirt thrown high in the air by the nimble feet of the countless host of buffalo.

“To flee from their wrath would have been the height of folly. All that could be done was, if possible, to find a high bank which they could not ascend and station myself on the highest cliff and rest content until the herd had passed by.

“If no such retreat was near, then I must rely on my trusty rifle, which was always with me, both day and night.

“To be sure, I did not depend on shooting them to lessen their number, but to divide the herd and turn their course.

“This was done by elevating the weapon over the herd just enough to miss their great humps that rolled on toward me like millions of iron hoops, bounding in the air at every little obstacle encountered.

“Then, when they were within 50 yards, the trigger was touched and the ball whistled furiously over their heads.

“The buffalo with one great impulse of dodging the missile, swerved to the right or to the left, owing to which side of them the bullet had passed. Then a great rent or split would open out and the moving mass would pass by on either side.

“With wonderful instinct those coming up in the rear would follow the footprints of their leaders and the great rent in the herd would remain open for hours at a time, for a quarter of a mile both in front and behind, when they would gradually come together in the rear of where I stood and thunder along in their mad career.

“It is true that one animal alone could not have made any impression on the great phalanx, but there is unity in strength and both were absolutely required in such time of peril.

“Such sights and sensations cannot be satisfactorily pictured to the millions of people now living and those unborn.

“I regret exceedingly that the Kodak was not a more ancient contrivance, so that a true representation could have been taken from life and handed down to those who will now only be permitted to read pen-pictures of the days which will never more return.

“As soon as the stampede ended the single herd was broken up into many smaller ones that traveled relatively close together, but led by an independent guide.

“Each small group is of the same strain of blood. There is no animal in the world more clannish than the buffalo. The male calf follows the mother until two years old, when he is driven out of the herd and the parental tie is then entirely broken.

“The female calf fares better, as she is permitted to stay with her mother’s family for life unless by some accident she becomes separated from the group.

“The resemblance of each individual of a family is very striking.

“Perhaps only a few rods marked the dividing line between them [the family herds], but it was always unmistakably plain, and each moved synchronously in the direction in which all were going.

“These groups are as quickly separated from the great herd after a stampede as is a company of soldiers from its regiment at the close of ‘dress parade.’

“The several animals know each other by scent and sound. The grunt similarly to a hog, but in a much stronger one and are quickly recognized by every member of the family. When separated by a stampede or other cause, they never rest until they are all together again.

“Their sense of smell is so wonderfully developed that neither animal nor man can pass them on the windward side within two miles without being immediately discovered.

“Indeed, often a herd has been stampeded by the scent from a single hunter even four miles away.”

Tragedy of a Stampeding Herd

Dary tells of a tragedy created by a stampeding herd. He quoted from Henry Shoemaker’s small booklet published in 1915 called “A Pennsylvania Bison Hunt.”

Shoemaker wrote that settlers were moving into Middle Creek Valley in central Pennsylvania and settling below the Seven Mountains where some 350 buffalo lived in summertime.

The wild buffalo were in the habit of coming down into the valley where conditions were easier with the deep snow and cold of winter.

The crops and haystacks of the new settlers would made this even more tempting.

So it happened that as the first winter of 1799-1800 became more and more severe, the hungry buffalo moved closer to the sheltered valley of Middle Creek.

One cold morning—led by a gigantic black bull the community had dubbed ‘Old Logan,’ after a Mingo chief—they came on the run into the barnyard of a settler named Martin Bergstresser.

“His first season’s hay crop, a good-sized pile, stood beside his recently completed log barn. This hay was needed as feed for the winter for his cows, sheep and team of horses.

“The cattle and sheep were standing close to the stack when they scented the approaching buffaloes. With Old Logan at their head, the famished bison herd broke through the stump fence, crushing the cows and sheep beneath their mighty rush and pulling to pieces the hay pile.”

Bergstresser in a nearby field cutting wood and his 18-year-old daughter Katie rushed to the scene and with Samuel McClellan, a nearby neighbor, they shot four buffalo.

The buffalo, terrified, stampeded up the frozen creek and disappeared.

“Woe to him, her, them or it that stood in the way of the mighty throng of infuriated, maddened animals!” Credit Nature Conservancy, Harvey Payne.

“Awful was the desolation left behind. The barn was still standing, but the fences, spring house and haystack were gone as if swept away by a flood. Six cows, four calves and 35 sheep lay crushed and dead in the ruins. The horses inside the barn remained unharmed.

“McClellan started homeward, but when he got within sight of his clearing he uttered a cry of surprise and horror. Over 300 bison were snorting and trotting around the lot where his cabin stood, obscuring the structure by their huge dark bodies.

“The pioneer rushed bravely through the roaring, crazy, surging mass, only to find Old Logan— his eyes bloodshot and flaming—standing in front of the cabin door.

“He fired at the monster, wounding him which so further infuriated the giant bull that he plunged headlong through the door of the cabin.

“The herd, accustomed at all times to follow their leader, forced their way after him as best they could through the narrow opening.

“Vainly did McClellan fire his musket. And when his ammunition was exhausted, he drove his bear knife into the beasts’ flanks to try and stop them in their mad course.

“Inside were the pioneer’s wife and three little children, the oldest five years, and he dreaded to think of their awful fate.

“He could not stop the buffaloes, which continued filing through the doorway, until they were jammed in the cabin as tightly as wooden animals in a toy Noah’s Ark.

“No sound came from the victims inside. All he could hear was the snorting and bumping of the giant beasts in their cramped quarters.

“The sound of the crazy stampede brought Martin Bergstresser and three other neighbors to the spot, all carrying guns.

“It was decided to tear down the cabin, as the only possible means of saving the lives of the McClellan family.

“When the cabin had been battered down, the bison, headed by Old Logan, swarmed from the ruin—like giant black bees from a hive.”

McClellan shot Old Logan as he emerged, but it was small satisfaction.

“When the men entered the cabin, they were shocked to find the bodies of the pioneer’s wife and three children dead and crushed deep into the mud of the earthen floor by the cruel hoofs.

“Of the furniture, nothing remained of larger size than a handspike.

“The news of this terrible tragedy spread all over the valley, and it was suggested on all sides that the murderous bison be completely exterminated.

“The idea took concrete form when Bergstresser and McClellan started on horseback, one riding toward the river and the other toward the headwaters of Middle Creek, to invite the settlers to join the hunt.

“Meanwhile, there was another blizzard but every man accepted with alacrity.

“About 50 hunters assembled at the Bergstresser home, and marched like an invading army in the direction of the mountains . . . They were out two days before discovering their quarry as fresh snow had covered all the buffalo paths.”

“The brutes were all huddled together up to their necks in snow in a great hollow space known as the Sink in the heart of the White Mountains.

“The hunters looking down on them from the high plateau above, now known as the Big Flats, estimated their number at 300.

“When they got among the animals, they found them numb from cold and hunger, but they could not move, so deeply were they crusted in the drifts.

The hunters shot and slit throats with long bear knives . . .

“After the last buffalo had been dispatched, the triumphant hunters climbed back to the summit of Council Kup where they lit a huge bonfire.

“It was a signal to the women and children in the valleys that the last herd of Pennsylvania bison was no more and that the McClellan family had been avenged!”

Photographer nearly trampled to death

Cowboys on horses chase stampeding bison out of the pine trees. Forsyth used his dual cameras to shoot these stereographic scenes. Montana Historical Society.

One of the men attracted to Michel Pablo’s grand roundup of his near-wild buffalo was Norman A. Forsyth, a young photographer who began selling stereo cards and viewers door-to-door while attending college at Wesleyan University in Lincoln, Nebraska.

After college he moved west, still selling for Underwood and Underwood, an early producer and distributor of stereographic views. Attracted by the scenic beauty of Yellowstone Park, Forsyth worked as a tour guide and stage driver in Yellowstone five summers, taking scenic stereographic views along the way, and then set up a photography studio in Butte where he sold them.

Fascinated by what he read of Michel Pablo’s great roundup of near-wild bison he took his cameras to Ronan, Montana. There he made friends with Charlie Russell, a cowboy painter also attracted to the dramatic buffalo action they saw every day.

Forsyth shot stereographic views and Russell painted and sketched numerous scenes over the first three summers during which the Pablo buffalo roundup shipped most of the animals to Canada.

One day Forsyth scrambled down into some trees to get the perfect shot as the cowboy wranglers brought in a herd of buffalo across the river toward the corrals.

The Wainwright, Alberta, newspaper reported Forsyth’s near brush with death as the buffalo herd leaped up out of the river and charged directly toward him.

“The entry of the buffalo into the corral came nearly being accompanied by a regrettable fatality.

“Mr. Forsyth, an enterprising photographer from Butte, Montana, being anxious to get some photos of the animals in the water, had stationed himself at a point of vantage amidst a clump of trees close to one of the booms in the river where he judged he would be out of path of the oncoming herd.

“However, they chose to take the bank directly below where he was standing, and before he could reach safety they were upon him in a mad, irresistible stampede.

“How he escaped being trampled to instant death is a miracle which even he cannot realize.

“He has a recollection of the herd rushing upon him and of having in some way clutched a passing calf which he clung to until it passed under a tree.

“He then managed to grasp a branch and although he was unable to pull himself up out of danger he was able to keep above the feet of the plunging herd.

“His dangling legs were bruised and cut by their horns and his clothes torn to shreds, but he still clung to the limb for life.

“Twice the herd passed under him as they circled back in an attempt to escape, but fortunately before he became exhausted they rushed into the corral.

“The Canadian Pacific officials and riders who knew the location chosen by Forsyth shuddered when they saw the animals rush in there and expected to find his body trampled out of semblance in the clay.

“Consequently, they rejoiced to find the luckless photographer slightly disfigured, but still hugging his friend the tree in his disheveled wardrobe.”

As the buffalo stampeded up out of the trees and into the corral, the cowboys rode to his rescue.

Scratched, bleeding and with his clothing ripped apart, Forsyth dropped out of the tree.

On the ground were his two costly cameras that shot dual picture stereographs, both shattered into many pieces and trampled in the mud.

He greeted his would-be rescuers with a sheepish grin, saying, “I think I have had enough of buffalo!”

[From a story told on her Blog [www.BuffaloTalesandTrails.com] by Francie M. Berg, Aug 25, 2020. ]

Racing a Train Across the Tracks

Tom McHugh discusses the leadership of a buffalo stampede in his book “The Time of the Buffalo.”

“The initiating animals, alarmed by some disturbance, dash off in headlong flight, thus giving the signal for retreat. Following by the others is virtually automatic. Some stampedes burst forth so suddenly that it is impossible to distinguish lead animals—if indeed there are any.

“At the beginning of a stampede, the buffalo rush headlong into a tight bunch, massing together with a herding instinct so powerful that the group can seldom be divided.

“This same stubborn tendency to bunch often thwarts ranchers attempting to drive a buffalo herd onto a different range.

“No matter what the technique—pushing with a line of men, chasing with jeeps or encircling with horsemen—the task is so difficult that many drives end in failure.

Buffalo can turn on a dime in the middle of a stampede and split off in several directions. Forsyth photo, MHS.

“Sooner or later one buffalo manages to outmaneuver its pursuers and squeeze through a minor break in the line, whereupon the rest of the animals quickly slip through the opening like so many links of a chain and the drive falls apart.

“Men within touching distance of the stampeding herd may shout and whistle and frantically wave their hands, but to no avail.

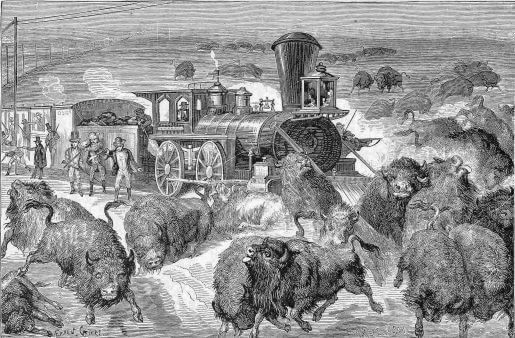

“Just as a single buffalo breaking through a line can disrupt a contemporary drive, a number of historic bison setting a determined course across the railroad tracks could derail a train. Once a few leaders had crossed, the rest of the herd would try to plunge after them, even when a train moved in to block the way.”

As Colonel Richard Dodge observed in 1872, the result would be utter chaos:

“At full speed and utterly regardless of the consequences, [the whole herd] would make for the track on its line of retreat. If the train happened not to be in its path, it crossed the track and stopped satisfied.

“If the train was in its way, each individual buffalo went at it with the desperation of despair, plunging against or in between locomotives and cares, just as its blind madness chanced to direct it.

Buffalo were known to set a determined course across the railroad tracks. Once a few leaders crossed, the rest of the herd plunged after them, even when a train was standing in the way. This could derail a train. Sketch credited to Wm. Hornaday.

“Numbers were killed, but numbers still pressed on, to stop and stare as soon as the obstacle had passed. After having trains thrown off the track twice in one week, conductors learned to have a very decided respect for the idiosyncracies of the buffalo . . .”

Helpful Stampedes

Stampedes can be dangerous, even today.

On the other hand, stampedes were an essential tool for ancient hunters planning a buffalo jump. One secret of every Buffalo jump was how to get the stampede just right.

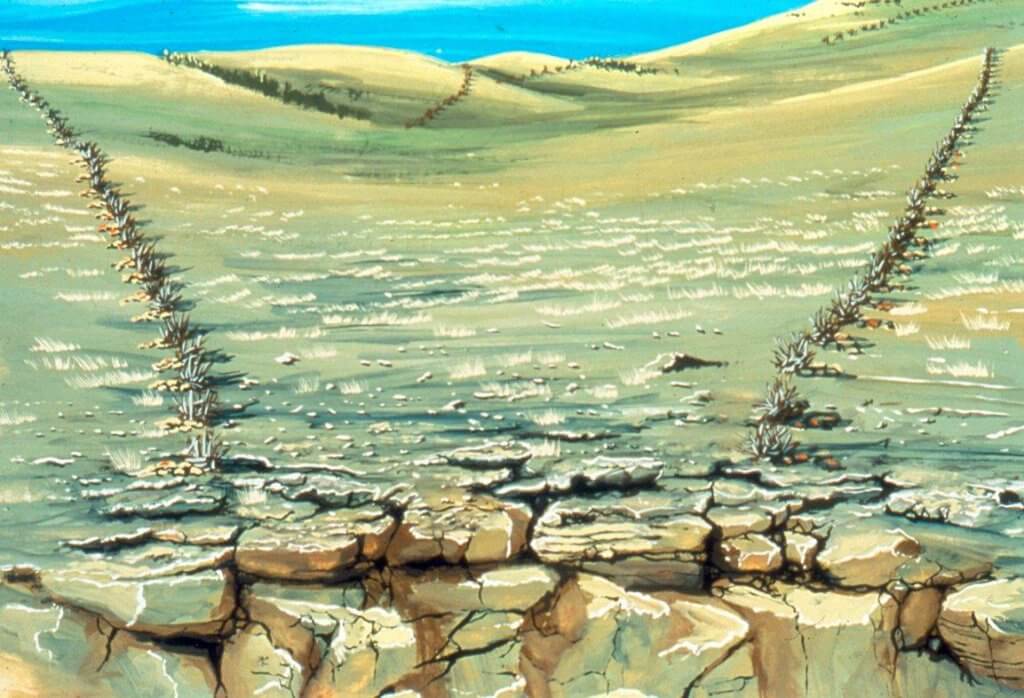

Stampeding a buffalo herd a quarter-mile before they came to the cutbank was a trick that often sent them over in confusion. Sketch courtesy of Jack Brink from Head-Smashed-In Jump.

Drive lines for ancient Buffalo Jumps may have looked something like this, funneling a stampeding herd toward the drop-off and a successful harvest. Courtesy JBrink.

No one knew their prey better than did those ancient hunters of the prairies and plains.

They had to be experts. For thousands of years they hunted buffalo without horses or guns.

Archeologists believe those ancient hunters started a stampede as they brought the herd fairly close to the cliff, probably less than a half-mile away.

Then the hunters pressed hard, plunging their prey into an all-out stampede. With huge bodies packed tight on all sides, stout horns slashing from behind, all charging at full speed—the lead buffalo could not stop or slow down.

The mass of horned animals behind would have prevented any escape. They could only run faster.

Their headlong charge carried them over the precipice at the last moment—for a successful harvest!

______________________________

NEXT: Crossbreeding Buffalo

___________________________

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog