2022 International Bison Convention a Great Success

NBA Executive Director Jim Matheson, along with many NBA members, attended the 2022 International Bison Convention (IBC) in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan this week.

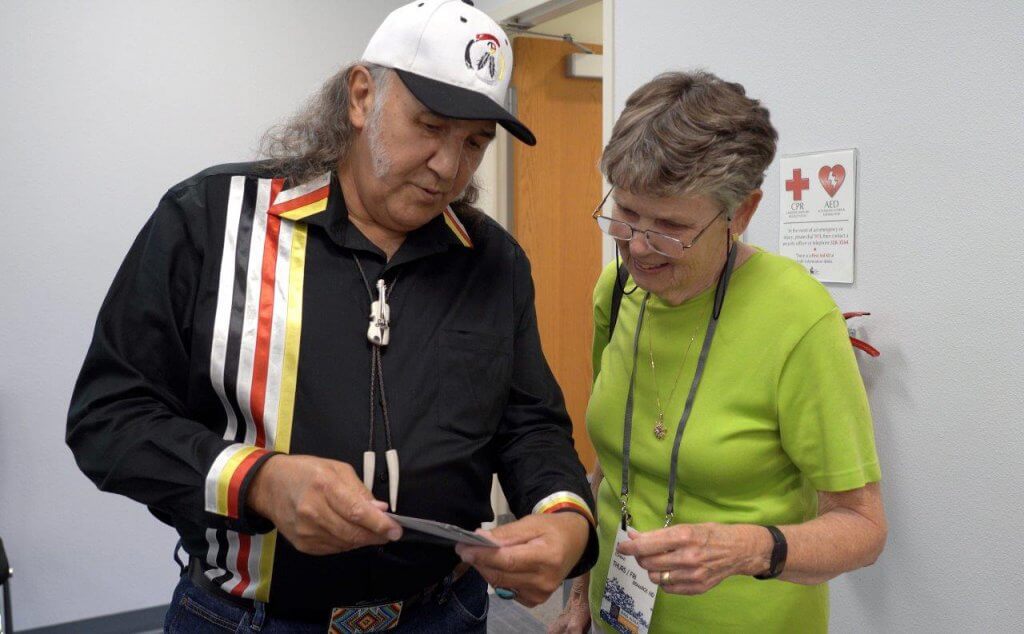

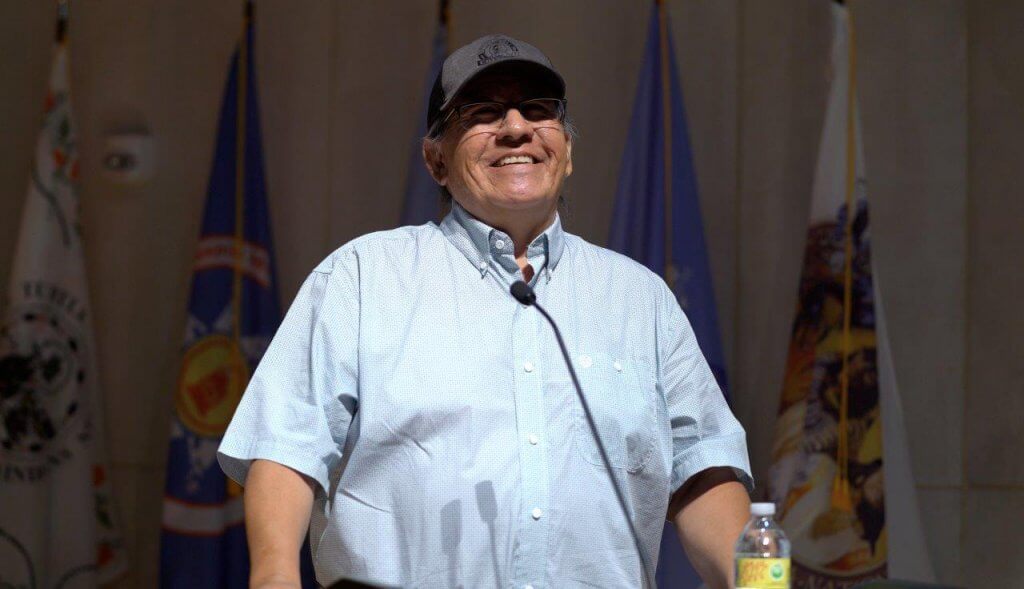

The conference was an enormous success, with hundreds of bison enthusiasts gathering in Canada to celebrate, learn, and network.

The International Bison Conference occurs every five years, with the NBA and the Canadian Bison Associaiton switching hosting duties each time. The last IBC was in Big Sky, MT in 2017.

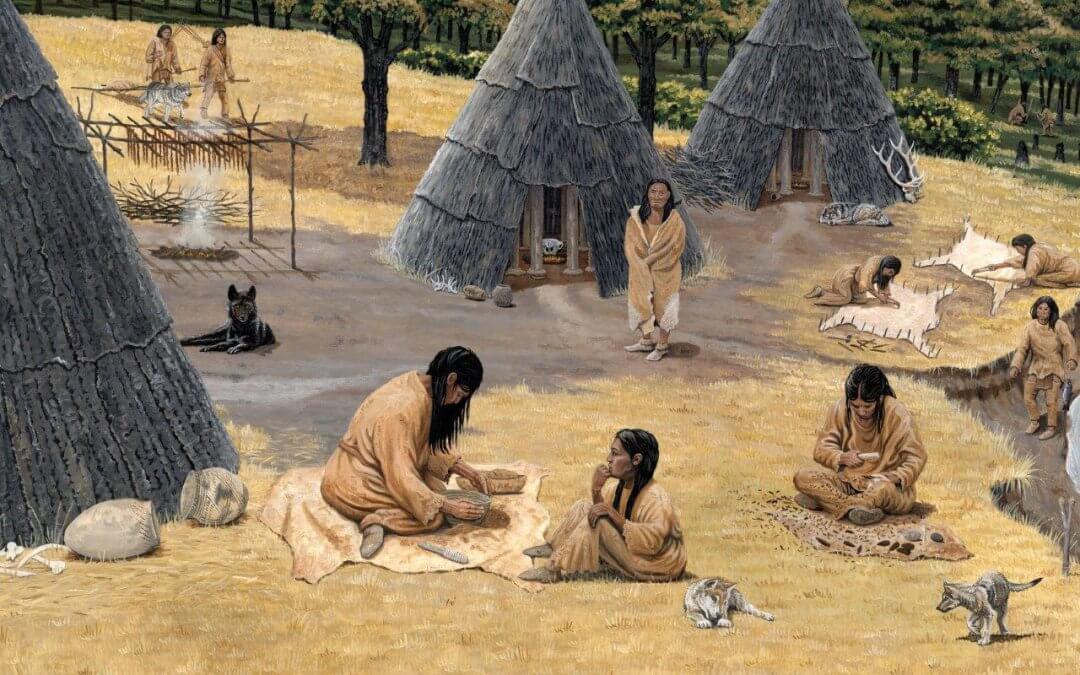

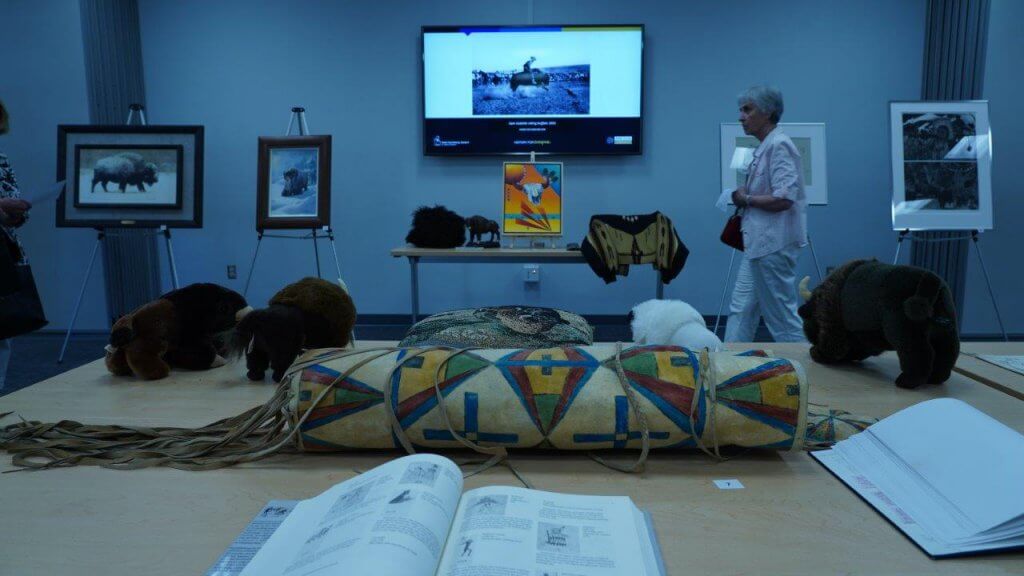

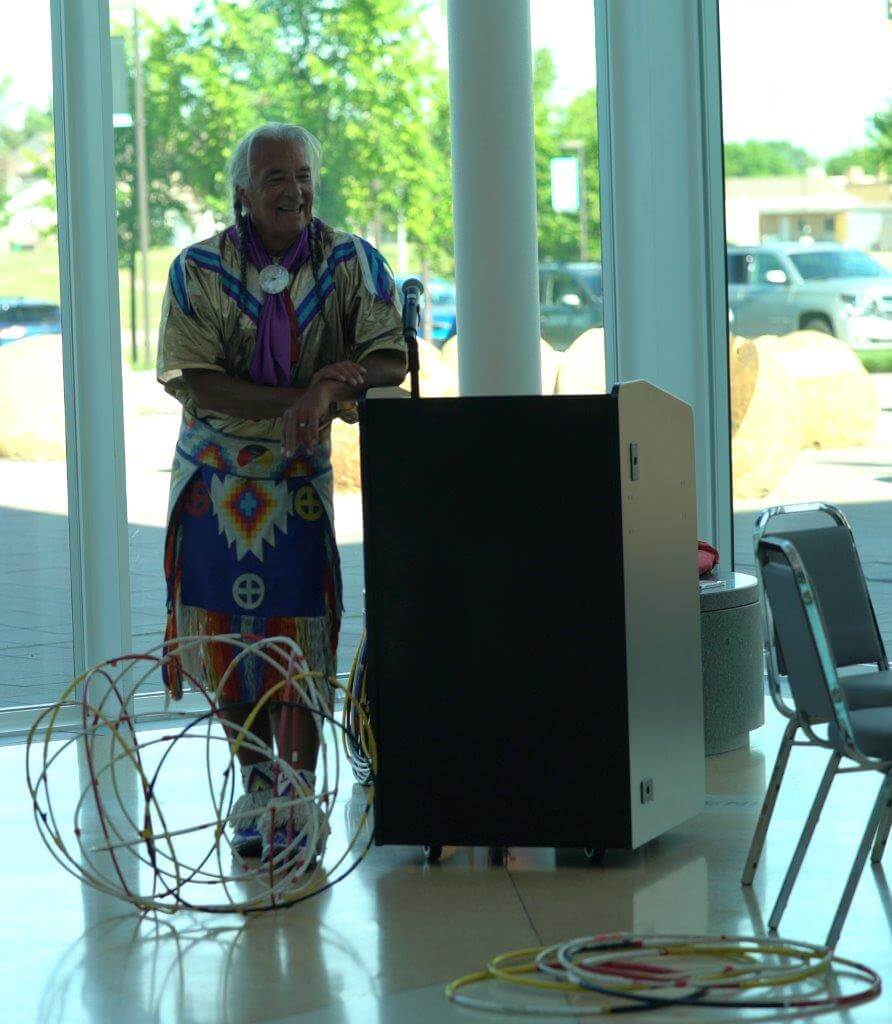

This year’s IBC had a diverse agenda that touched on all aspects of the species, from production to research to conservation to culture, the conference had it all.

Attendees were treated to wonderful gourmet meals at each sitting, all of which featured local Canadian bison. The CBA pulled out all the stops with entertainment the first two evenings, concluding with a banquet dinner on Thursday night that included a fun auction that raised significant funds for the association, graciously served by auctioneer, Brennin Jack.

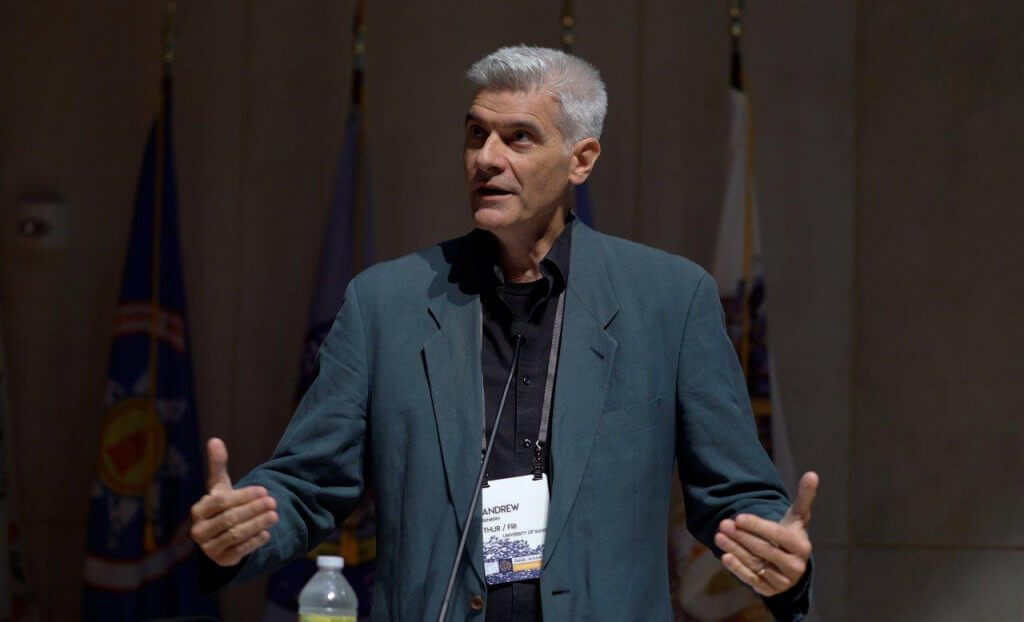

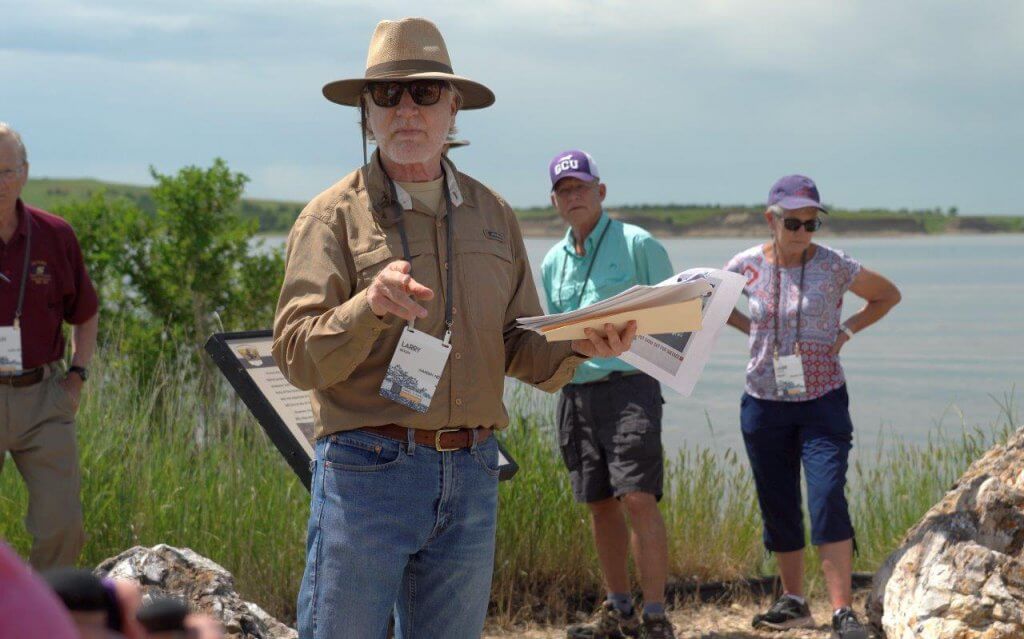

Matheson provided opening remarks and participated as a judge in the convention’s poster session, which featured innovative research by North American graduate and PhD students.

Said Matheson, “This year’s IBC was very well organized, planned and facilitated and was enjoyed by all in attendance.

“The get together was as much a reunion as it was a conference, and the CBA certainly raised the bar with IBCs to come. Kudos to all involved in making this IBC a tremendous success.”

NBA Weekly Update for July 15, 2022

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog