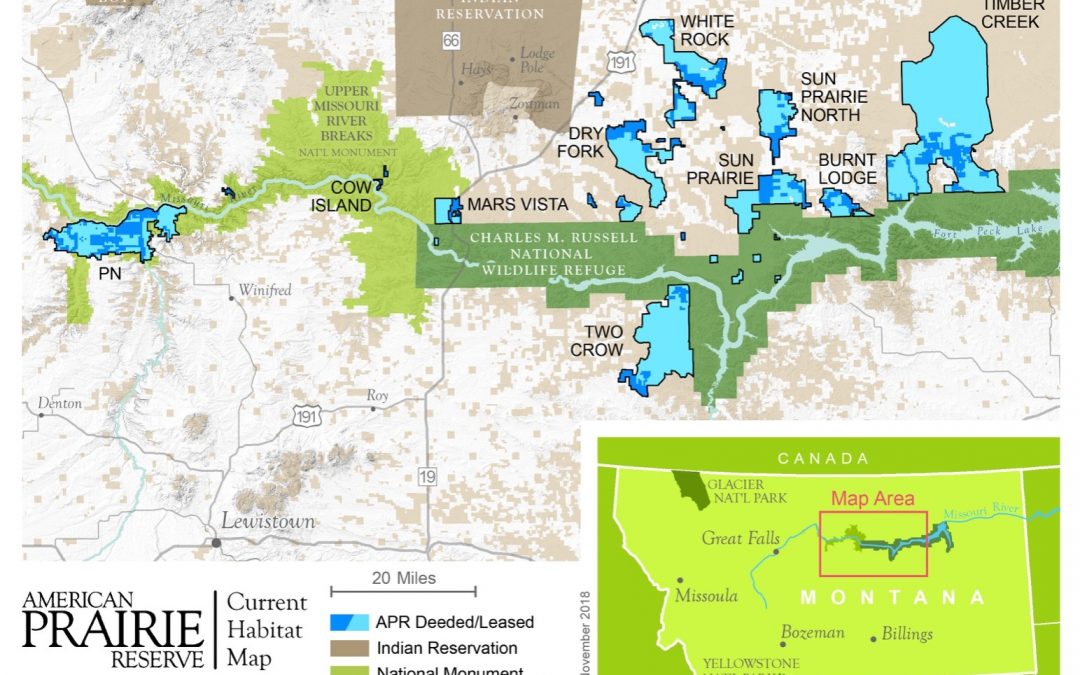

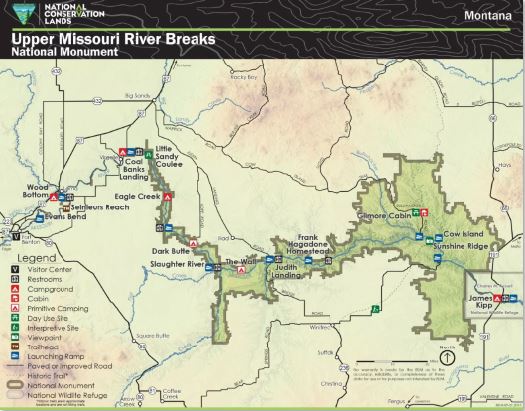

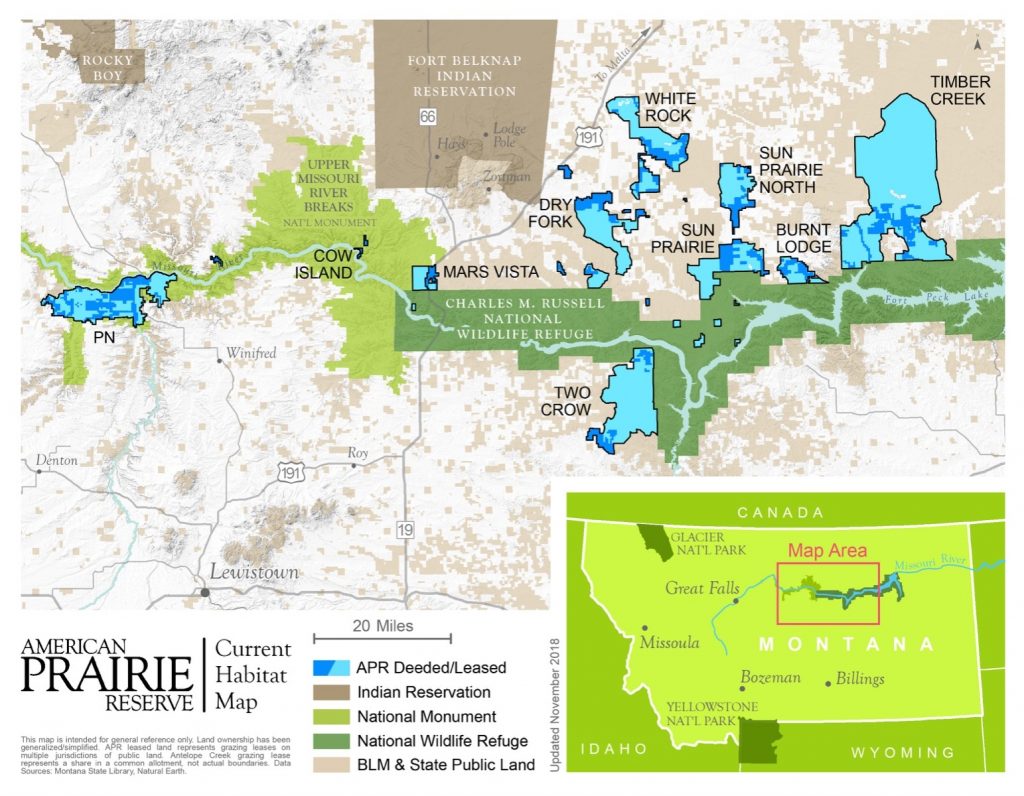

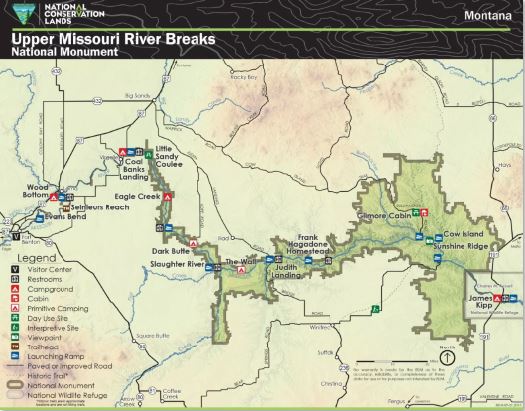

Blue areas depict lands purchased and leased by the American Prairie Reserve in the last 19 years. The APR plan is to connect them with Federal lands including the Charlie Russell National Wildlife Refuge (dark green) and the Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument (light green) and other state and federal and perhaps Indian lands. APR Map.

In northcentral Montana an enormous wildlife project is taking shape in a bold new way that is shaking the foundations of community development and progress—to bring about what has been called the American Seringetti.

The American Prairie Reserve—APR, or simply the Prairie Reserve–on the upper Missouri River is an ambitious plan to develop just such a place as that vast and unspoiled Serengeti National Park in Tanzania, which still experiences the last of the world’s great wildlife migrations.

This Prairie Reserve would be the largest nature reserve in the continental United States. It aims to turn back the clock and restore the wildlife that roamed here two centuries ago. All the large predators: grizzly bears, packs of wolves, mountain lions will be here—along with great herds of wild buffalo.

This Montana area was discovered in 2000 by a group of environmentalists who proclaimed it critical for preserving grassland biodiversity.

“One of the largest intact landscapes in the Great Plains,” they said. “A top priority” and “pristine grasslands.”

One year later, a member of that group, a biologist named Curt Freese, teamed up with a Montana native named Sean Gerrity and together they formed the American Prairie Reserve (APR). Gerrity, a former Silicon Valley consultant, says the idea was to “move fast and be nimble,” in the manner of high-tech start-ups.

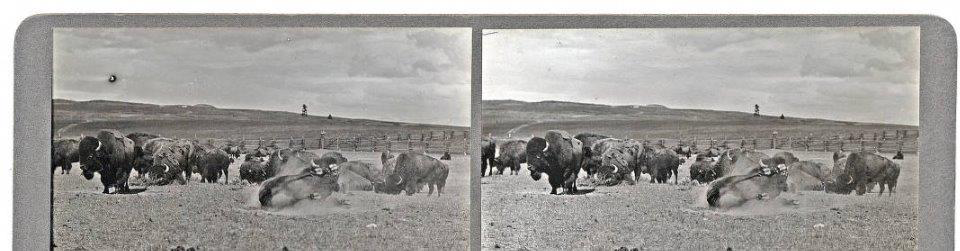

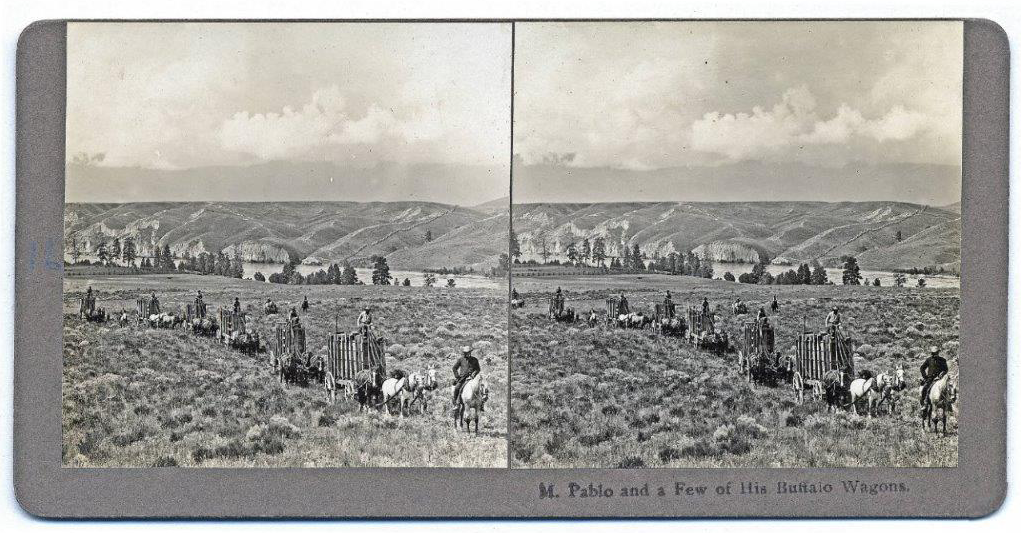

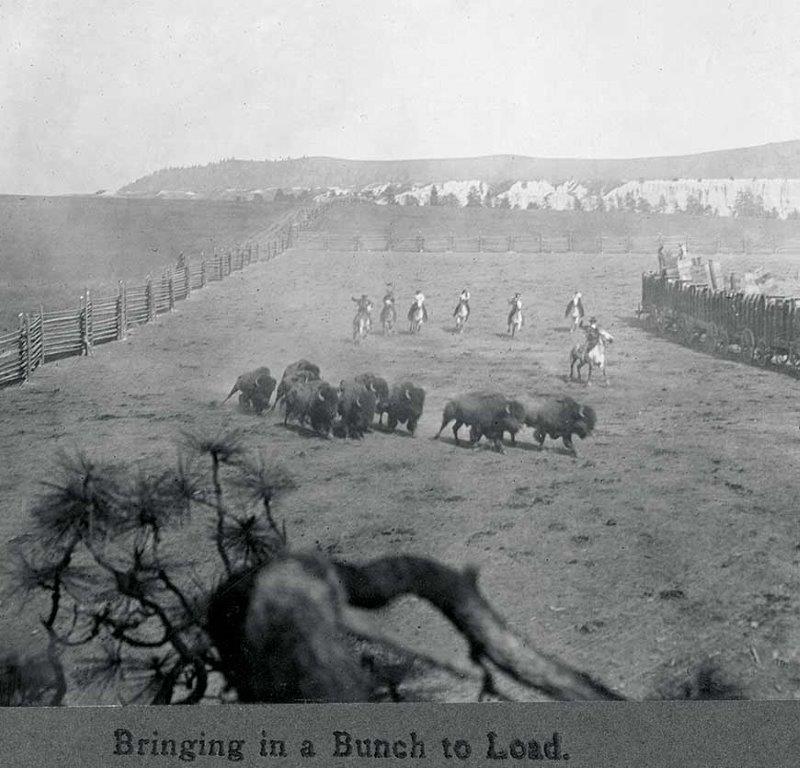

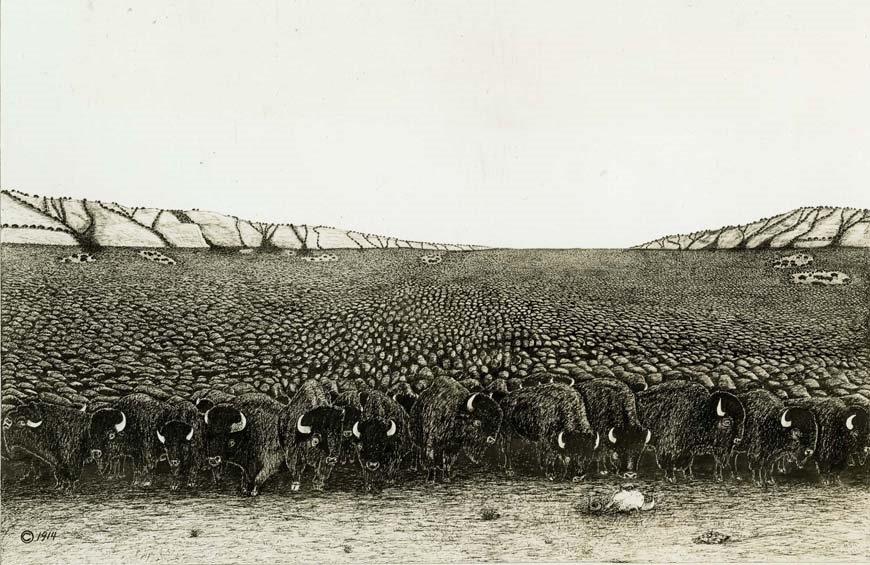

They would remove the hundreds of thousands of cattle grazing the land, stock it with 10,000 buffalo, tear out divider fences, restore native vegetation, and create conditions whereby the missing wildlife would return and thrive in a natural setting.

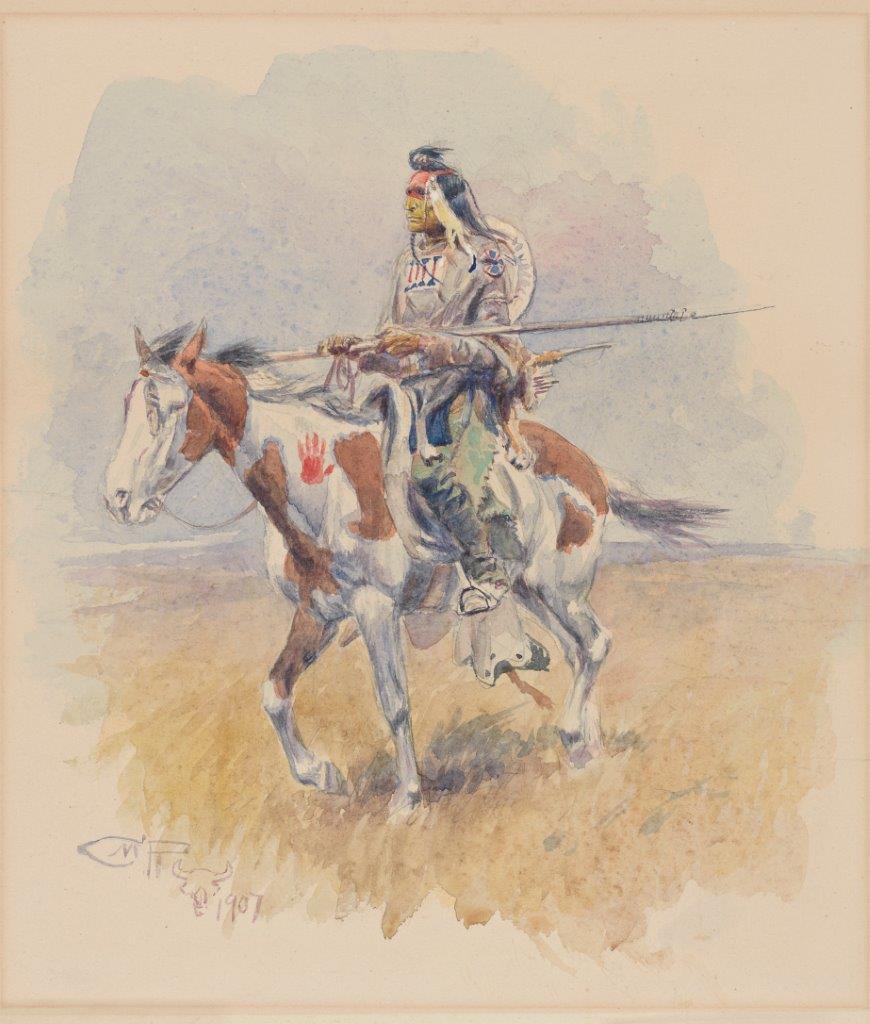

Buffalo on the move. The American Prairie Reserve plan is to replace cattle on their land purchases—and adjoining lands—with 10,000 free-roaming buffalo. Painting by CM Russell.

They began raising private donations with the goal of bringing together 3.2 million acres, or 5,000 square miles, of mixed private and public grassland along the Missouri River, acquiring ranches at what they said were market prices.

Think Big

In the 19 years since that time, the Prairie Reserve group has raised $160 million in private donations, nearly all of it from out-of-state high-tech and business entrepreneurs across the U.S. and beyond.

They have acquired 30 properties, totaling 104,000 acres. To this they added about three times that—more than 300,000 acres—in grazing leases on adjacent federal and state land. This is what owners do when they purchase land with grazing rights.

These environmentalists are claiming lands in a unique and ambitious way. They are buying up the private ranches one by one, adding each to large tracts of federal and state land along the upper Missouri river, and then working to set aside all these lands in ways that can be difficult to ever reverse.

Others have long purchased lands for conservation, such as The Nature Conservancy, but none have done it in the large-scale they propose, and few have had the ambition, as the Prairie Reserve does, says National Geographic, of retaining ownership and management authority of that land and adjoining publicly owned lands.

Best of all, in the view of the new Prairie Reserve, enormous pieces of federal and state land span the area. Linking them together with available private lands makes sense, particularly with the possibility of controlling all of it into the distant future.

The ranches purchased are all strategically located near two federally protected areas: the 1.1 million-acre Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge and the 377,000-acre Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument, according to National Geographic (Feb.2020, p69-89), which partners with Prairie Reserve in the Last Wild Places initiative. Other Federal and State lands intersect as well.

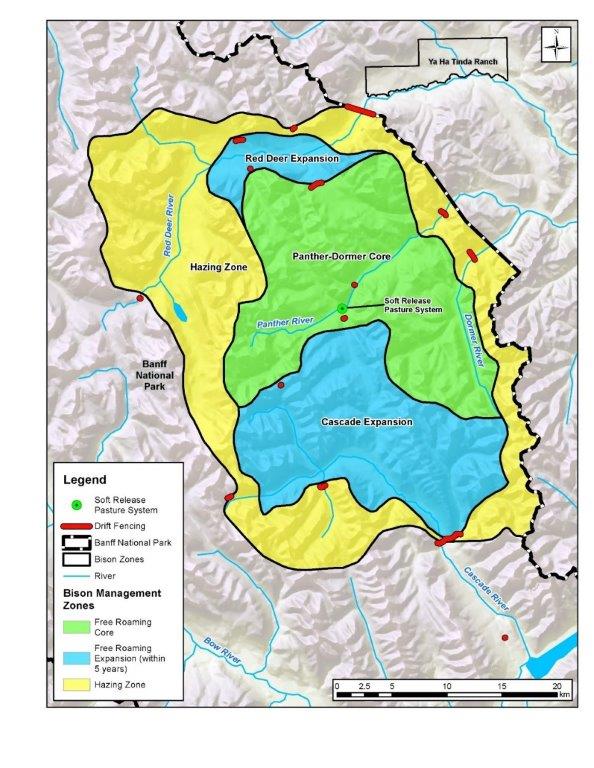

The Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument cuts through an awe-inspiring stretch of scenic rugged country, planned to be part of Prairie Reserve’s set-aside refuge, but disputed by local ranchers. National Conservation Lands map.

Even a nearby Indian Reservation, Ft. Belknap with tribal bison, has joined the Prairie Reserve in talks about letting their buffalo roam free in the area, an idea that has great appeal for Native Americans with their buffalo-hunting heritage and culture.

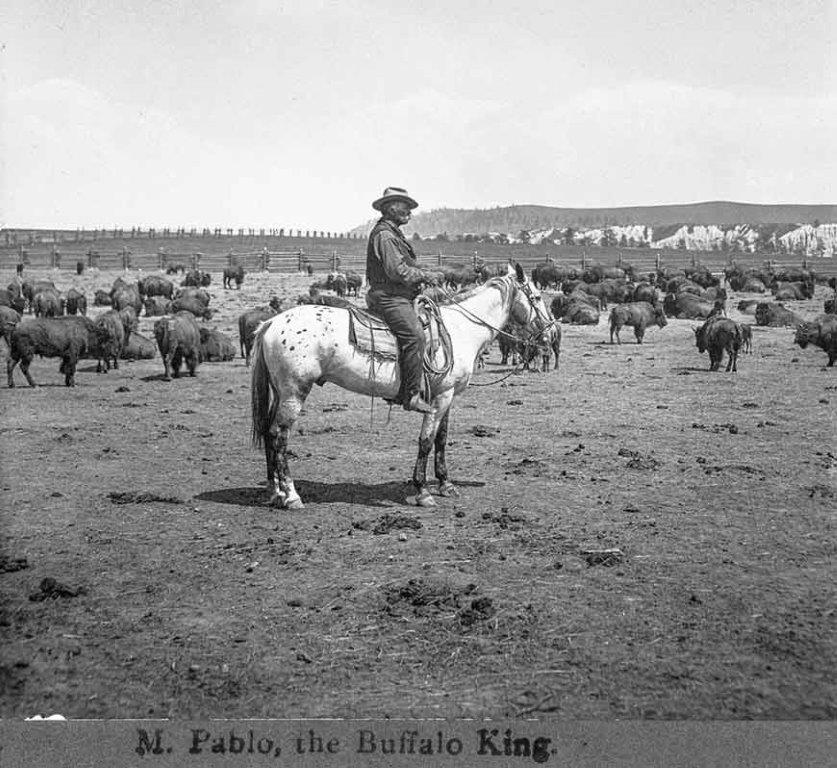

At a powwow, Kenneth Tuffy Helgeson, a member of the Nakoda Tribe, said the reserve’s goal of bringing back thousands of wild bison to the plains will help restore a crucial part of his tribe’s culture. The animals were nearly eradicated from the prairies by white settlers.

“It’s a reminder of days past,” says George Horse Capture Jr., a member of the Aaniiih Tribe. “It’s hard to put into words. To me they are a symbol of strength, endurance and the failure—the absolute failure—to go the way of the dodo bird. They were teetering, but now they’re back.”

Tribes and others are given regulated opportunities to hunt American Prairie’s bison.

Grassland biodiversity requires abundance, Freese says. “You’ve got to think big.”

Think of the refuge and monument as the trunk of a tree, Gerrity adds.

“In buying nearby properties we’re trying to expand the girth of the tree,” adding branches to the trunk and bringing about easy movement of wildlife between river systems and grasslands.

Beauty of the Land

Sean Gerrity, founding co-father, stands on one of the vast ranching properties his Prairie Reserve recently purchased. It looks like a miniature Grand Canyon—a panorama of deep, white canyons cut through by a wide, winding river.

“What you’re seeing here is the incredible beauty of the Missouri River out in front of us,” he declares. “Those beautiful cliffs and the raking light coming across in the afternoon.”

His goal is to “rewild” this swath of the Great Plains and return all the species that once lived here, before white settlers arrived. Wolves, grizzly bears, mountain lions and 10,000 wild bison.

Gerrity points down to the valley below. “Over here would be some elk,” he says. “Over here bison. On the riverbanks would be a mama grizzly bear with two or three little cubs walking along the mud there.”

The Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument spans 149 miles of the Upper Missouri River. Cutting through rugged badlands, it is little changed in over 200 years since Meriwether Lewis and William Clark travelled through on their epic journey of exploration. Photo by BLM.gov.

These animals can be seen in Yellowstone Park. But the APR goes it even better. A new kind of national park that is free to the public and privately funded through both small donors and some of the wealthiest people in the world.

For Gerrity, who moved back home to Montana from Silicon Valley, where he ran a firm that consulted for companies such as AT&T and Apple, the project promised a different kind of long-term investment.

“To work on something—pour your heart into it—and arrange it like a giant work of art and the public would by and large appreciate and realize it would last far, far beyond my lifetime? That just seemed like a dream come true,” Gerrity says.

This is one of only a few intact grassland ecosystems in the world, he says, and he wants to fully restore it before it disappears.

“This wildlife habitat is going away and there is almost none left,” he warns. “This is the last bit in the great plains, for the most part, where we can do a project of this size.”

Trying to be Good Neighbors

Multimillion-dollar donations have poured in from heirs to the Mars Candy Company—Forrest Mars, Jr. and John Mars— a German billionaire, Hansjoerg Wyss, Susan Packard Orr, and top executives in the finance industry. Current board members, Erivan and Helga Haub, Gib and Susan Myers and George and Susan Matelich, are also major donors.

Even though the money comes almost entirely from out-of-state, the staff of American Prairie Reserve, experienced negotiators, have tried to be good neighbors. They made all the right moves in their goal of bringing together this huge plot of lands along the Missouri river.

They established a firm Montana base, placing what they call their national headquarters in Bozeman, Montana. They hired as many employees and staff with a Montana connection as they could.

They encourage hunting, fishing and other recreation on the Prairie Reserve—all of which appeals to Montanans.

They’ve donated beef and bison to local Native American food banks, sponsored rodeo athletes, and donated buffalo-hunting events for local fund-raisers, according to National Geographic, which assisted by sponsoring a “Living with Wildlife” conference for ranching neighbors, who are concerned about the arrival of more predators on the prairies.

Importance of Collaboration

The APR staff talk reassuringly of their desire—and in fact, need—to collaborate with local communities and ranchers.

Their website praises teamwork. “When appropriate and when it will lead to smoother, faster and better execution, we act collaboratively to accomplish results. We proactively contribute, and act, on ideas to improve cross team collaboration and enthusiastically support the efforts of others to do the same.

“We work to understand the goals of others, and effectively communicate our own, and make consistent efforts to help each other achieve them.”

Conner Murnion bails off a bronc at the Milk River Challenge Open Rodeo during the Phillips County Fair. Photo by Pierre Bibbs, Phillips County News

Both the Bureau of Land Management and Montana Parks, Fish and Wildlife seem ready to support the APR request for a change in rules for leases, which would enable bison to displace cattle.

Montana PFW Director Martha Williams, stresses the word collaboration, too, while supporting APR in its desire for bison to be classed as wildlife. She sees the plan to change the status of bison from livestock to wildlife as an opportunity.

“Wild bison have been successfully restored under a variety of management regimes and in a wide range of ecosystems,” Williams said in a press release. “But in order for a proposal to proceed in Montana, it must be devised collaboratively, taking into account the concerns of landowners and communities small and large, and it should follow the model of other successful wildlife restoration efforts.”

Tom France, Regional Executive Director of the National Wildlife Federation assures people that the APR group has local support. “The fact is, an overwhelming majority of Montanans support restoration,” he says.

On their website Prairie Reserve emphasizes the value of teamwork and collaborating with others.

Yet APR is very clear in its goals. They are out in plain sight: “Our mission is to create the largest nature reserve in the continental United States, a refuge for people and wildlife preserved forever as part of America’s heritage.”

“When we’re done with it,” Garrity told National Geographic, “it’s going to last hundreds of years.”

Is the area really empty of people?

It’s true the APR does have the support of many Montanans. They have always supported the freedom of enjoying nature, hunting, fishing, outdoor recreation of all kinds, and keeping it available for all.

When viewed from the far-off crowded seaboard states, where the majority of Americans live, it may seem that central Montana is an area empty of people and unneeded for agriculture, as Prairie Reserve staff tell their story.

“We watched a video narrated by Tom Selek, and most people watching it would have believed that nobody was really here,” says Deanna Robbins, a rancher from Roy and co-founder of the United Property Owners of Montana, an advocacy group.

“The video never shows a ranch. It rarely shows a person, and totally ignores that there are families on the land with lives and communities that support and depend on them.”

But people do live here. Hundreds of men and women have planted their roots in Phillips County for well over 100 years—have worked hard to build strong communities, invested their lives, their incomes and their families. Literally, blood, sweat and tears.

Phillips County Fair brings out the crowds. Though sparsely settled, it is cattle country and made up of close-knit communities. Photo by maltachamber.com.

This is cattle country, so it is sparsely settled. Still, it’s not empty.

Furthermore, every rocky ridge has its own history, its own story. Every badlands creek bed that runs high in springtime and only trickles through by August, could tell a tale or two. Is all this to be obliterated with the goal of returning these coulees to nature?

Every town, no matter how small, has its doctors, dentists, bankers, teachers, churches, and businesses of all kinds, courthouse, public buildings, its city boosters and all the rest—built up through all those years—just like any small new England town.

For its part, APR makes the argument that the reserve, once completed, will be a relatively small island in a sea of agriculture.

Not so small, local people contend—the area is larger than Yellowstone Park. As large as Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Park put together.

Anna Brown takes a fall during the Mutton Busting event at the Youth Rodeo. She finished in fourth place with a score of 61. Photo by Pierre Bibbs, Phillips County News.

Already the Prairie Reserve swallows up the 30 ranches purchased, with a planned 20 still to go. That’s at least 50 families gone from parts of seven counties, much of it in Phillips County.

Why can’t they stop now, be content with what they have?

Sure, there’s room for some buffalo on this range. Prairie Reserve already runs nearly a thousand buffalo there.

Prairie Reserve already has nearly a thousand head of buffalo grazing their property in the area. Photo by National Park Service.

Maybe that’s enough. Why would 10,000 be that much better?

APR also makes a case that their project will bring in thousands of tourists.

But ranchers don’t see the benefits of tourism replacing the close-knit vibrancy of their own community.

Roger Siroky, a rancher who lives near Roy and Bohemian Corner, foresees just the opposite effect. Towns drying up without agriculture to sustain them.

“All these businesses, ranches and farms, they all complement each other so you have a vibrant community, with all the various businesses and services that serve that community.

“It is total fallacy how the APR is going to [bring all this] tourism. It’s going to destroy the economic vitality and financial workings of the whole area.

“As people leave, there are less people. This business shuts down, and then that business shuts down until you have a few people left as an island without the infrastructure remaining to serve a producing community, and it simply goes downhill.

“It gets to be a domino effect,” he adds.

World hunger continues

Furthermore, ranchers feel a strong commitment to help provide food for a hungry world. They know that throughout the world, people are going to bed hungry every night.

By the year 2050 the world population is estimated to increase by over 35 percent to 9 billion. The U.S. Department of Agriculture says this will cause the demand for food to nearly double—a rise of 70 to 100 percent.

In 2017, Sub-Saharan Africa had the highest prevalence of food insecurity (55 percent) and severe food insecurity (28 percent), followed by Latin America and the Caribbean (32 percent food insecure and 12 percent severely food insecure), and South Asia (30 percent and 13 percent), according to USDA. A lot of hungry people.

Drought in Somalia in the Horn of Africa. Up to 178,000 children were expected to be impacted by severe acute malnutrition between July 2019 and June 2020. Adding to challenges were swarms of locusts destroying crops near the end of 2019. Photo by Stuart Price.

“We provide food for the world,” says rancher Alex Bellmayer. His family has run cattle on the shortgrass prairie near Malta, Montana for more than a century.

“It’s a lot of work,” he said. “But it’s a good lifestyle.”

“Agriculture is Montana’s number one industry,” agrees Gladys Walling of Winifred. “When my husband and I purchased land with allotments on public lands administered by the Bureau of Land Management, we worked with BLM in managing those allotments. In a dry year, we limited the number of cattle and moved our cattle out earlier.

“The APR is requesting that the BLM allow them to graze bison year around and remove interior fencing on their Federal allotments connected to their private property.

“My hope is that the BLM will continue leasing with good management of these allotments and deny the APR’s request,” she adds.

BLM range specialists explain to ranchers the merits of cross-fencing and rotating cattle frequently from one smaller pasture to another to make the best use of available grass.

But instead, the APR theory seems to be that buffalo will “know” when they are overgrazing and naturally make the best use of the grass in their single enormous pasture. So no divider fences?

“Having the traditional use of the Federal grazing districts is a large part of many of these operations out here, and it certainly plays a role in growing protein for a hungry world,” says Robbins.

Robbins understands the APR appeal to outside investors, but she’s not buying.

“It’s such a marketable pitch—this big American Serengeti,” she said. “They don’t have to stick to the truth much, and people fall for it.”

“Agricultural producers have protected this land. It is pristine due to 100 years of agriculture caring for it,” Robbins added.

Greg Oxarart, a 60-year-old rancher who has lived in Phillips County his entire life, says the outside money financing the project bothers him.

“I just don’t believe in their mission,” Oxarart said of the APR. “They plan on taking over this whole county. Malta would be off the map if they have their way.

“People who make a living here take good care of the land because if they don’t they’re soon gone.” They also help to feed the nation, he said. It’s the contribution farmers and ranchers make to the hungry people of the world and they are proud to do this.

How can Young People return Home to Ranch?

“I can’t believe that people would support what they’re trying to do,” says Bill French, an 81-year-old rancher who owns property abutting the reserve. “They’re trying to ruin what I’ve worked the last 60 years of my life to build up. They don’t say that, but that’s what they’re doing.”

One of the most distressing aspects is how the APR enterprises aims to co-opt the future. If they succeed, land set aside for conservation is land that will be unavailable for cattle far into the distant future for ranching families to expand.

Ranchers contend that their millions of fund-raising dollars gives APR an unfair advantage when ranches come up for sale.

Younger generations already have difficulty financially, taking over ranching from parents and grandparents. It can take a lifetime to get the land to pay for itself.

Phillips County Farm Bureau President Tom DePuydt explains it is difficult for agriculture producers in the county to compete financially with the American Prairie Reserve for land.

“We are seeing young families coming back to many of these places, but it’s almost like there’s a cloud hanging over their head,” said DePuydt. “What’s their future if these people keep coming in with that type of money? Are they just going to get squeezed out if they can’t even compete for leases?

“There are a lot of kids who want to come home and ranch. We see the land around here priced really high for the recreational value, and agriculture won’t pay for it.”

“Not everybody has enough money set aside to sell at a lower price,” said Robbins “Making a go in ranching is challenging, and the APR’s ability to raise funds and receive grants makes it all the harder for ranchers to compete for land.”

Rancher Greg Oxarart moves cattle up road in south Phillips County. He has concerns about the impact of Prairie Reserve in cattle country. Photo by Lauren Chase, Montana Stockgrowers.

Oxarart has three sons who would like to come home to Phillips County to ranch, but land prices, which he says have increased since APF began buying property, are making that difficult. If four or five people banded together to buy land in order to make a living, he’d support that, he said.

The land is beautiful, he says, but it’s difficult to make a living here because it’s not intensely productive with cattle ranching its best use, Oxarart says.

“That’s why not many of them will live here,” he says of APR supporters. “When it’s 40 below in December, it becomes a challenge to get things done. Then you depend on your neighbors when you have breakdowns.”

Concerns for their Cattle

Other issues divide as well. Cattle men and women can’t help feeling deep concerns over basic difficulties bound to confront them if bison are established, and large predators not currently living on APR lands are brought in, as they have been in Yellowstone Park.

For example:

- How can ranchers protect their livestock from the relentless goal of environmentalists introducing still more large predators such as packs of wolves, grizzly bears and mountain lions? Already, wolf packs brought into Yellowstone Park have multiplied and spread into many Montana counties.

- How will ranchers protect their livestock from devastating diseases like brucellosis that run rampant in elk and other wild animals?

- Will all those miles of exterior fencing be built high enough and strong enough—and consistently maintained well enough through all kinds of weather and conditions to hold buffalo—including those lone bison bulls on the rampage?

These are serious, important questions. But they all hinge on that larger question. Which vision or goal do Montanans want most for their citizens?

Vibrant communities can disappear

Are Montanans willing to sit by and watch thriving communities shattered and broken apart, in order that people can enjoy the wildlife refuges and parks that have always been there for them?

The only difference being, with Prairie Reserve they’ll be under another name, without cattle, with outsider, big money control, and surely some long-lasting bitterness over how changes have taken place.

Montanans have always supported the freedom of enjoying nature, hunting, fishing, outdoor recreation of all kinds, and keeping it available for all.

Yet having it forced on them in this way can be galling. The high-handedness of these outsiders is appalling. They have discovered something good and seem to believe they can take charge of it and keep it in “pristine” condition better than local people.

The federal bureaucracy of BLM seems all too willing to change leasing rules to accommodate the wishes of Prairie Reserve. Even Montana state wildlife officials approved a plan to allow bison to be categorized as wildlife outside of Yellowstone National Park.

“It worries me more than water, wind, drought, prices,” says Craig French, a rancher whose family is involved with the anti-APR movement in Phillips County.

“I see them coming in with big money, buying up ranches and walking over the top of the people who are already here,” says ranch owner Conni French. “For them to be successful in their goals, we can’t be here, and that’s not OK with us.”

French, who owns C Lazy J Ranch, believes in stewardship of the land and says she will never sell her spread to the reserve.

“We are the best hope to keep this land here,” French says. “I really feel like ranchers—these land stewards—are the best option for conservation.”

Two visions for the land, two goals that collide and divide

There are two visions here, two separate goals for this land. One continues the local vision for progress as American settlers have always understood it. The other is the dream of turning the clock back to nature in a big way.

The concept of “wilding,” so precious to the environmentalist, means something different to the rancher. It means obliterating—destroying all progress.

Malta, a town of 2,000 population, could dwindle, say ranchers. They worry that each ranch APR acquires is one lost to the community, draining taxes from county treasury, children from schools, and business from stores. Photo by maltachamber.com.

The land can’t revert to nature in the way the Prairie Reserve supporters envision without clearing away the history—and the people. It means selling off all the cattle that graze this productive country.

This is what concerns the ranchers, who are realists. Its about two very different visions of how people want to use land in the American West. And who decides?

On the Great Plains of Montana, conservationists, environmentalists, and some tribes want to rewind the clock and return wild bison to the shortgrass prairie.

But ranchers say if that happens, their way of life—their very culture—will disappear. Sadly, it seems to be true.

They say each acre taken from cattle grazing threatens ranching operations and hurts the local economy.

Robbins said, “We feel the APR is not being honest. What APR really wants is a takeover of Federal land and control of how it’s managed.

“APR wants the rules changed to year-round grazing for their bison, rather than seasonal. The private land they own is a pretty small piece in proportion,” Robbins added. “They want to buy as little land as they can and control the Federal Land.

“Now they want the BLM to change the rules on your public land so they can graze year-round, tear out interior fences… If BLM changes its rules for APR then they’re actively empowering APR to bulldoze Montana families and communities.”

“We should not allow them to conduct a radical experiment on BLM land,” testified Chuck Denowh, of the United Property Owners of Montana.

Small Town Businesses Decline and Disappear

In Phillips County, where the American Prairie Reserve has most of its land holdings and 86,000 head of cattle graze the land, many neighbors remain skeptical of the ambitious and groundbreaking conservation effort to save unbroken native prairie, viewing the growing reserve as a threat to a way of life and productive agricultural ground that fuels rural economies.

“I wasn’t aware of this purchase, but I think the loss of a ranch, and especially the continuation of additional ranches, will have an effect on our county,” said Phillips County Farm Bureau President Tom DePuydt, of a recent sale to Prairie Reserve.

For its part, APR makes the argument that the reserve, once completed, will be a relatively small island in a sea of agriculture.

Not so small, local people contend, since it displaces the 30 ranches already purchased, with a planned 20 still to go. That’s 50 families gone from parts of seven counties, and a great deal of Phillips County. They ask, why can’t they stop now, be content with what they have?

“Our country is real,” says Bill French, whose biggest fear is that the lands being set aside by the reserve will eventually be declared a national monument, sealing their future. “These people at American Prairie think they’ve discovered it.”

French’s grandparents homesteaded in the area in 1917, his wife’s, in 1910. He has served on the local soil and conservation district for 55 years.

“For these people to introduce or want to introduce free-roaming bison would basically put every rancher within reach of them out of business,” said Dee Boyce, who ranches between Lewistown and Grass Range.

Ranching is what makes Malta tick. Bellmayer said without it, his town would just be a brown smudge along the Amtrak railway line between Chicago and Seattle.

“If you have nothing but wild bison and antelope, then you might as well take the town out,” a rancher from the nearby town of Malta recently said on a local public radio station. “They’re destroying not only a way of life,” said another. “They’re destroying a very vital economic base which is a foundation of America.”

Boyce says, “I want the people in Lewistown and anywhere else to stop and think how they’re going to replace production agriculture as we know it. Agriculture is an important thing to this community and to me as a producer.

“For these people to introduce or want to introduce free-roaming bison would basically put every rancher within reach of them out of business.

“There are other options for conservation” other than APR, says Conni French. “Ranchers and other land stewards have been caring for and restoring this landscape for generations. This attitude of stewardship continues today.

“Local communities are working together with multiple stakeholders to create a win-win scenario,” she assures them. “Ranchers, wildlife, communities, economies and this unique ecosystem can all benefit from this type of collaboration.”

Yet, many ranchers feel—in some ways—that they are fighting this battle alone, with little support from town neighbors.

Maybe it is time for all Montanans to take a closer look at what is here, and what’s at risk of being destroyed. Surely many will say, “Stop! It’s enough.”