Part II: Saving the Buffalo from Extinction

His life adventures took him from his home in Kansas to the frozen Canadian North and the steaming jungles of Africa.

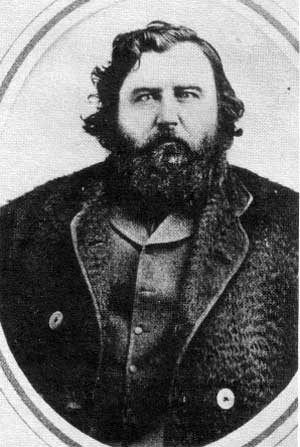

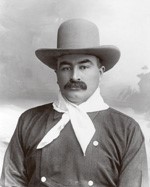

Buffalo Jones was a flamboyant speaker, a dreamer, and an entrepreneur who risked his profits over and over in buying, selling and shipping buffalo.

He prospered and suffered as a farmer, buffalo hunter, town developer and rancher. An expert roper, he captured calves in Texas and New Mexico. And, as a friend of President Teddy Roosevelt through the new American Bison Association, he was appointed as the first Superintendent of Yellowstone Park, in charge of restoring that depleted buffalo herd.

His greatest contribution was—not only capturing and raising a profitable buffalo herd—but finding ways to buy and sell buffalo and ship them across North America to help start new herds.

As a child, Jones caught and tamed small animals. He made his first money by capturing and selling a squirrel. That “transaction” Jones said “fixed upon me the ruling passion that has adhered so closely through my life.”

Jones said that he conceived his buffalo rescue plan in 1872.

He said he had killed “thousands of buffalo” in his hunting days and he regretted it.

“I am positive it was the wickedness committed in killing so many that impelled me to take measures for perpetuating the race which I had helped almost destroy.”

Filled with remorse, he set aside his big buffalo rifle, gathered some of the last wild buffalo calves and committed himself to helping the buffalo survive and thrive throughout North America.

He bought buffalo from as far north as Winnipeg in Canada and sold buffalo across the North American continent to help get parks and private owners started.

According to Ken Zontek, in Buffalo Nation: American Indian Efforts to Restore the Bison, during the last days of the wild buffalo, Buffalo Jones and his assistants went four times out to the buffalo ranges from his ranch near Garden City, Kansas, down into the Texas Panhandle, and captured 60 buffalo of all ages. Not all, however survived, or made the trip home.

Jones was a flamboyant speaker and told entertaining tales of those trips—roping buffalo calves, grabbing their tails, and hand-throwing them.

He explained to his biographer, Henry Inman, that on his first calf-catching expedition he had to protect his charges from wolves that closed in on the calves he had thrown and tied.

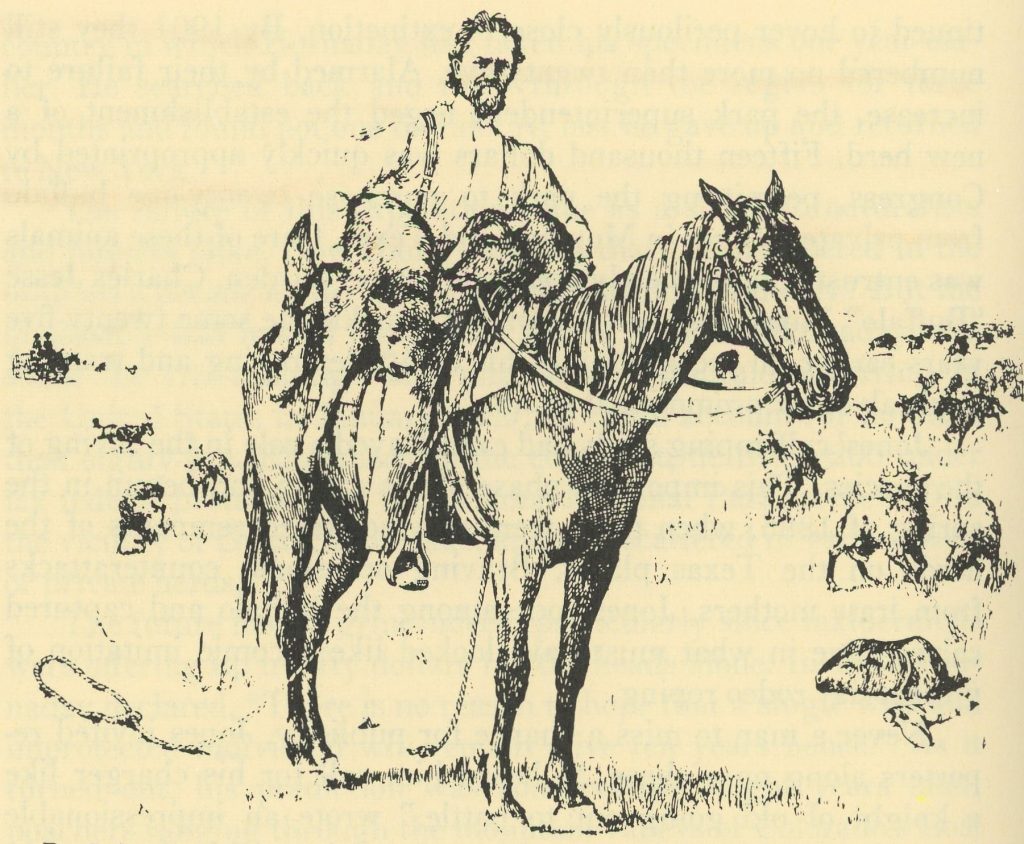

> With a buffalo calf under each arm, Buffalo Jones kept the Texas wolves at bay until the supply wagon arrived. Sketch by J.A. Ricker from Buffalo Jones’ 40 years of Adventure.

Jones could not pause while he worked to catch as many calves as possible, he said, so he left an article of clothing on each calf to warn away the hungry wolves.

“Half-naked and burdened by a calf under each arm,” Jones then rode back to aid his captives. Finally, his support wagon, furnished with pails of milk, arrived and saved the day.

Emerson Hough, accompanying Jones’ second expedition, provided a vivid description of Jones’ capture method. “Up came his hand, circling the wide coil of the rope. We could almost hear it whistle through the air. … In a flash the dust was gone, and there was Colonel Jones kneeling on top of a struggling tawny object.”

During that buffalo-saving trip, Jones, like Goodnight, was “compelled to kill” a ferocious mother buffalo with his revolver. “An unwished result and much deplored, for we came, not to slay, but to rescue,” wrote Hough.

Jones successfully captured and mothered up many calves with milk cows, brought along each time for that purpose.

This usually involved an initial fight until the calf and cow grew attached to each other during the long trip from Texas back to Kansas.

Buffalo Jones’ last two calf-catching expeditions in 1888 and 1889 proved noteworthy for a couple of reasons.

First, Jones roped adult buffalo and tried to drive them home—unsuccessfully, however. Jones explained that the grown buffalo “took fits, stiffened themselves, then dropped dead, apparently preferring death to captivity.”

Many of the 60 he roped died, both calves and adult buffalo.

Second, it was on this expedition that he claimed he roped the last wild buffalo calf of the southern range.

“I whirled the lasso in the air … [and] laid the golden wreath around the neck of the last buffalo calf ever captured.”

Zontek notes that Jones—like the other rescuers of buffalo—was a buffalo hunter and a westerner. He saved buffalo near the ranch where he worked and lived as well, as making calf-hunting trips farther afield.

Like the others, Buffalo Jones worked hard to make a living. He saw nature as something beautiful, created to serve humankind.

The Buffalo Jones’ herd numbered 50 by 1888.

That year he had a chance to purchase 86 Canadian Plains buffalo originating from the herd of Tonka Jim McKay. Jones willingly paid $50,000, an average of $582 each.

Shipping them from Winnipeg to Kansas proved difficult, however, and added to the expense. Of the first thirty-three he cut out to drive to the railroad, a number of buffalo broke and ran back to the herd.

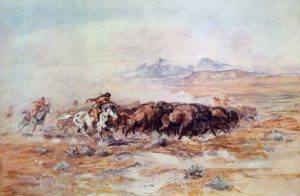

> Rounding up and shipping 86 buffalo from Winnipeg to Kansas proved a challenge.

Three more were killed by others in the railroad car near St. Paul. Thirteen escaped when unloaded for water in Kansas City and stampeded through town.

Shipping the remaining buffalo home to his ranch at Garden City, Kansas, proved a challenge, but once there, they increased rapidly.

He soon owned over 150 head and began selling buffalo to zoos, parks and private individuals.

Like Charles Goodnight, Jones experimented with crossing buffalo with cattle. He also learned what did and did not work from Goodnight. Often the cross-breds were not fertile, and most did not show the desirable traits he wanted.

By 1895 Jones was deep in financial trouble.

Forced to sell his ranch and holdings, he dispersed his buffalo. Some went to Pablo and eventually back to Canada. Others shipped to west coast locations.

As a friend of President Theodore Roosevelt through work with the American Bison Society, Buffalo Jones requested and was granted an appointment as the first superintendent and game warden of Yellowstone National Park.

There he led the effort to rebuild the remnants of the Yellowstone buffalo herd, with a mix of buffalo from numerous sources. From long experience, he knew exactly where to find viable buffalo herds and how to handle them.

Unfortunately, Jones was not so skilled working with employees and eventually lost favor and his ideal job.

He continued lecturing on his experiences with buffalo and his African adventures, but gained a reputation for exaggeration, and even hints of shadiness in his dealings.

Pete Dupree kept his buffalo herd intact

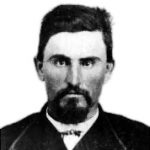

In what is now South Dakota, Fred Dupris (also spelled Dupree) watched the buffalo disappear from Dakota Territory.

The buffalo had migrated farther west because of settlement in the eastern Dakotas and hunting pressure throughout the territory during the late 1860s. For 15 years they were gone from Dakota Territory.

The son of a distinguished French-Canadian family in Quebec, Fred Dupree arrived in South Dakota in 1838 and prospered through a variety of ventures, including fur trading and cattle ranching, according to Dave Carter, director of the National Bison Association.

> Fred Dupree, Fur Trader and cattle rancher on the Cheyenne River. SD Historical Society.

He married a Minneconjou Sioux, Mary Ann Good Elk Woman, and set up a trading post in a pleasant wooded area along the Cheyenne River within the Great Sioux Indian Reservation, just at the point where Cherry Creek flowed into the Cheyenne.

As a Native American woman, Mary Ann held rights to run cattle on the reservation, and they built up a herd of 200 range cattle, along with running the prosperous trading post.

There they raised a large family, with 10 children.

Fred Dupris became one of the state’s leading pioneers. As each of their children married and started a family, he and his wife built another log cabin in the cottonwood trees along the river.

Late in his life, when Fred Dupree was in his 70s, amazingly, the last 50,000 buffalo migrated back onto the Great Sioux Reservation.

It was December of 1880. The Duprees immediately notified relatives and friends and prepared for a winter buffalo hunt. They also invited the young missionary Thomas Riggs from the Oahe Mission, just east of the Missouri River, to join them.

Riggs wrote a detailed description of the three-month buffalo hunt, so we have a first-hand, documented account. (See “Buffalo Heartbeats Across the Plains,” Winter Hunt in Slim Buttes, by FM Berg, page 26.)

That winter of 1880-1881 they spent in tepees and tents in the Slim Buttes was one of the coldest, heaviest-snow winters in years, Riggs said.

Soon after—that spring or the following one, in 1881 or 1882, Pete Dupree and some of his brothers, and likely sisters, too, went out to rescue buffalo calves.

They likely drove a buckboard wagon pulled by a team of horses, with outriders leading pack horses for carrying home additional buffalo meat, always much needed by their many families.

Until 1883, plenty of buffalo still grazed there on the Great Sioux Reservation—but almost nowhere else.

Fred Dupree, the old fur trader is historically credited for “sending out his sons” to capture the buffalo calves. However, by then he was an older man in his mid-70s and stayed home by the fire while his family went out on their last winter hunt. His sons were grown men.

One might imagine the old trader telling visitors that he sent out his sons to rescue calves, even if it didn’t quite happen that way. Again, conflicting stories abound.

A more likely scenario may be that Mary Ann Dupree and her sons and daughters hatched the details of their plan to rescue buffalo calves during their long three-month buffalo hunt.

Mary Ann was the woman who suggested the missionary Thomas Riggs join them and share their family tent in the Slim Buttes. She was very resourceful and known by her husband and others as “a good woman.”

In the extreme cold of that winter they spent many hours together in the tent and were, naturally, very familiar with the Native Americans’ deep concerns about buffalo soon becoming extinct.

After 15 long years of heartbreak over their disappearance, the buffalo had returned to them.

They had migrated right into the Duprees’ own backyard, so to speak. If these Native people failed to help them now, who would?

Some historians suggest that the Duprees brought their buffalo calves home in their wagon in February 1881, at the end of that long, cold hunt in the Slim Buttes.

But there’s no logical way that could have happened.

First of all, wild nine- and ten-month-old buffalo calves would have been much too large and aggressive in February to be handled and would never have gentled well.

Second, there was no extra room in the wagons. The Dupree wagons carried full loads of hides and meat—no room for lunging, brawling half-grown calves! The long trip home through deep crusted snow with heavily loaded wagons was difficult enough without trying to wrestle big calves.

Third, Riggs made no mention of hauling buffalo calves home in his summing up of the three-month hunt’s successes.

Besides, until 1883, plenty of wild buffalo still grazed there on the Great Sioux Reservation—but almost nowhere else within riding distance.

Another story, that their father Fred Dupree picked up the calves on the Yellowstone River in earlier years, also seems unlikely. The fragile calves would hardly have survived that long trip home without milk and good nourishment. Many such captured calves died of starvation long before they ever reached a home ranch.

Most likely the location was the south fork of the Grand near the juncture where the north and south forks flow together or within a few miles.

South Dakota historians writing for 4th graders have identified the south Grand River as the site where the Duprees found their buffalo calves. That was only a couple of days drive by wagon from their home on Cherry Creek—around 60 miles. [1. South Dakota State Historical Society, “Buffalo in South Dakota, Unit 3, Lesson 3: Preservation of the Buffalo,” The Weekly South Dakotan: South Dakota Treasure Chest for 4th-Grade History, www.sd4history.com.]

Also, the Grand River is identified as the place where Pete caught his five calves by Wayne C. Lee, writing in “Scotty Philip, the Man Who Saved the Buffalo.” [2. p157 and p225. Caxton 1975.]

That Pete Dupree immediately found fairly gentle range cows and quickly “mothered up” his buffalo calves was another major achievement. In this effort he may well have had help from his mother and sisters—and thus avoid the typically high death loss of “rescued” buffalo calves.

> Buffalo calves often died of malnutrition before they could be successfully “mothered up” with a range cow. SD Game, Fish, Parks.

Mothering up—trying to coax half-wild range cows to accept the strange-smelling calves, and the lanky youngsters to nurse and bond with the low-slung cows—could not have been easy. But once accepted by their adoptive moms, the gangly buffalo calves grazed contentedly on lush reservation lands, and within a few years, began raising calves of their own.

While the other four buffalo rescuers engaged in considerable buying and selling of buffalo, even donating many buffalo for new public herds, Pete Dupree kept his growing buffalo herd intact, and allowed them to increase naturally on the Great Sioux Reservation.

> Pete Dupree kept his growing buffalo herd intact grazing and multiplying on the Great Sioux Reservation. Photo by Stephen Pedersen.

He neither sold nor purchased buffalo. As buffalo, they required little or no care. They just naturally multiplied. And occasionally, a stray buffalo joined his herd.

Also, from time to time they interbred with range cattle, resulting in the crossbred animal, then called “cattleo.”

For ten years Pete’s herd increased. Then in 1898 Pete Dupree died.

Scotty Phillip took over the bison rescue

His younger sister’s husband, Douglas Carlin handled the sale of his estate. In a highly fortunate move, Carlin found the right buyer for Dupree’s buffalo.

James “Scotty” Phillip was born in Scotland in 1858 and traveled throughout the American West panning gold, working as a scout, and ranching in Wyoming, before marrying Sarah “Sally” Larribee, a Lakota Sioux, in 1879, according to Dave Carter, of the National Bison Association.

> Like the Duprees, Scotty and Sally Philip intended to do what they could to save the buffalo from extinction.

They settled down near Fort Pierre in South Dakota in 1882, prospering in the cattle business, running cattle on the Great Sioux Reservation, under Sally’s Indian allotment, as well as on privately owned lands the purchased.

When the chance came to buy Pete Dupree’s buffalo for $10,000, Sally urged her husband to buy.

“We must not let the buffalo die. My people might need them again,” Sally Philip is quoted as saying.

It is likely, she was thinking not only of Lakota needs for food, shelter and clothing, but also their spiritual and emotional ties to buffalo.

Scotty agreed that helping save the buffalo was a way he could support his Native friends, who often were not treated well.

Philip sent six cowboys to round up the Dupree herd and drive them the 100 miles to his pasture. His nephew George Philip, a budding lawyer, was pressed into service and later wrote about the difficult venture.

George Philip wrote of the formidable task in which he and the cowboys finally brought to the Philip pasture gate 83 buffalo, plus a number of cattalo.

They’d had to let go of the old renegade bulls that escaped from their several roundups.

> Philip’s cowboys had to let of old renegade buffalo bulls that refused to cooperate in the roundup. Later most were shot for their heads. Photo by Chloe Leis.

Philip declared the cattalo worthless and quickly sold or butchered them, according to his biographer, Wayne C. Lee, in “Scotty Philip: The Man Who Saved the Buffalo.”

He believed that buffalo were unique, and deserved to retain their natural traits. (This attitude prevails today among breeders, and is listed among the ethics policies adopted today by both the National Bison Association and Intertribal Buffalo Council. No cross-breeding, unless accidental. This is sometimes expressed as “let buffalo be buffalo.”)

The Phillips became willing and devoted buyers and protectors of the Dupree buffalo herd. Like the Duprees, they took their mission to save buffalo seriously. They intended to do what they could to save the buffalo from extinction.

When the U.S. government opened the Great Sioux Reservation lands in South Dakota for homesteading, Scotty Philip asked that 3,500 acres on the Missouri River bluffs north of Fort Pierre be set aside for grazing native buffalo.

Congress agreed and located the reserve just north of Philip’s own buffalo pasture, leasing it to him for $50 a year.

On the Missouri River bluffs his buffalo herd of several hundred head became a well-known tourist attraction. Special excursion boats brought visitors upriver from Pierre to view the rare and amazing buffalo ranging in the rugged badlands.

One day a delegation of Mexican officials from Juarez came to see the tourist buffalo. They laughed and declared the big bulls lazy and slow moving. Definitely unworthy of comparison with their own fiery Mexican fighting bulls, they thought.

Scotty Philip and his Fort Pierre friends took offense and challenged a bull fight.

This actually took place in January 1907 in the bull-fighting ring in Juarez.

Fortunately, Phillip’s nephew George was called on again to attend the two buffalo bulls shipped there, when a blizzard emergency kept Scotty home with his cattle. George described the Mexican bull-Buffalo fight in delightful detail for historical records. (See “Buffalo Heartbeats,”Mexican Bullfight, page 182.)

Native buffalo owners grew their buffalo herds

Thus, these five family groups are especially honored as having saved the buffalo from extinction.

Men received the credit from early historians for saving the buffalo, in the fashion of the times. However, women were much involved, as well, and are celebrated today.

Native American women went on all the big hunts and watched the great herds disappear. They despaired over the ruthless slaughter by commercial hunters with powerful, long-range rifles.

Women and children, too, undoubtedly helped to bottle feed calves, and coax the adoptive milk cows and half-wild range cattle mothers to bond with their gangly new calves.

The men “may have been considered ‘Buffalo Kings’ by their fellow ranchers, but it was the wives who should be remembered as ‘Buffalo Queens,’” says Susan Ricci, manager of the Buffalo Museum in Rapid City.

Modern historians rightly give the families a great deal of credit for saving the buffalo. Not just the men.

These were the five family groups who made special efforts to care for their buffalo herds and raised sustainable adult herds for many years:

- Sam Walking Coyote and his herd purchasers Charles Allard and Michel Pablo in western Montana;

- James McKay and neighbors in Manitoba, Canada;

- Pete Dupree and his herd purchasers the Scotty Philips in South Dakota;

- Charles and Molly Goodnight of Texas;

- Buffalo Jones of Kansas.

Doubtless, other people were involved in raising buffalo for a time here and there. Nevertheless, the herds of these five flourished and eventually became the foundation for literally all the Plains buffalo herds populating the world today.

All were westerners, all hunted buffalo and all were ranchers.

The first three of these groups had Native American roots and knew well the cultural importance of buffalo in the lives of their people. They all held a deep cultural stake in survival of the Buffalo.

Rather than butchering or selling the increase, the Native families mostly grew their herds, multiplying and strengthening their numbers. They cherished the natural wild traits of the buffalo without trying to alter them. Cross-breeding, when it occurred was accidental, the result of cattle and buffalo sharing the same ranges.

> Native American families grew their herds and cherished the wild traits of the buffalo without trying to change them. South Dakota Game, Fish and Parks.

The white ranching families, the Goodnights and Buffalo Jones, respected the natural world, cherished their buffalo and appreciated their own roles in preserving them. However, perhaps more than the others, both these non-Indian families hoped to reap economic benefits and engaged in much buying and selling of buffalo.

Also, both experimented with cross-breeding in the hope of developing hardier, more productive beef animals. This was generally unsuccessful, and today cross-breeding is discouraged and violates the Code of Ethics of both the National Bison Association and the Intertribal Buffalo Council.

Much has been written through the years about the role that noted conservationists from the east played in pulling bison back from the brink of extinction.

The work of William Hornaday, George Bird Grinnell, President Theodore Roosevelt and others of the American Bison Society was important in setting aside public lands for buffalo and providing long-term sustainability for public herds. They were visionary conservationists, and also had hunted buffalo.

But Ken Zontek, buffalo historian, raises an interesting point in his book. He says not much attention has been paid to westerners who actually kept the young calves alive.

He notes that, while conservation-minded people in the east put forth a valuable effort in founding wildlife parks and sanctuaries for long-term survival of the buffalo, they would have failed, had it not been for westerners who caught and saved calves in their own localities.

His observation is absolutely true.

Once the buffalo were thriving in viable herds, men and women from the east made sure they were safe long-term and multiplying in buffalo parks and sanctuaries throughout the United States.

However, if not for the five rescuing groups and their families caring for young starving calves in their own communities, the Plains buffalo would not have survived as a species.

Without them there’d be no buffalo alive today.

To a greater or lesser extent their vision involved the survival of an endangered species.

Their herds flourished and eventually became the foundation of all the Plains buffalo herds now populating the United States and Canada.

These are the families—with boots and moccasins on the ground—who kept the buffalo species alive at their lowest ebb.

_____________________________________________________________________________

NEXT: Banff restoration Project

_____________________________________________________________________________

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog