Signing the Buffalo Treaty

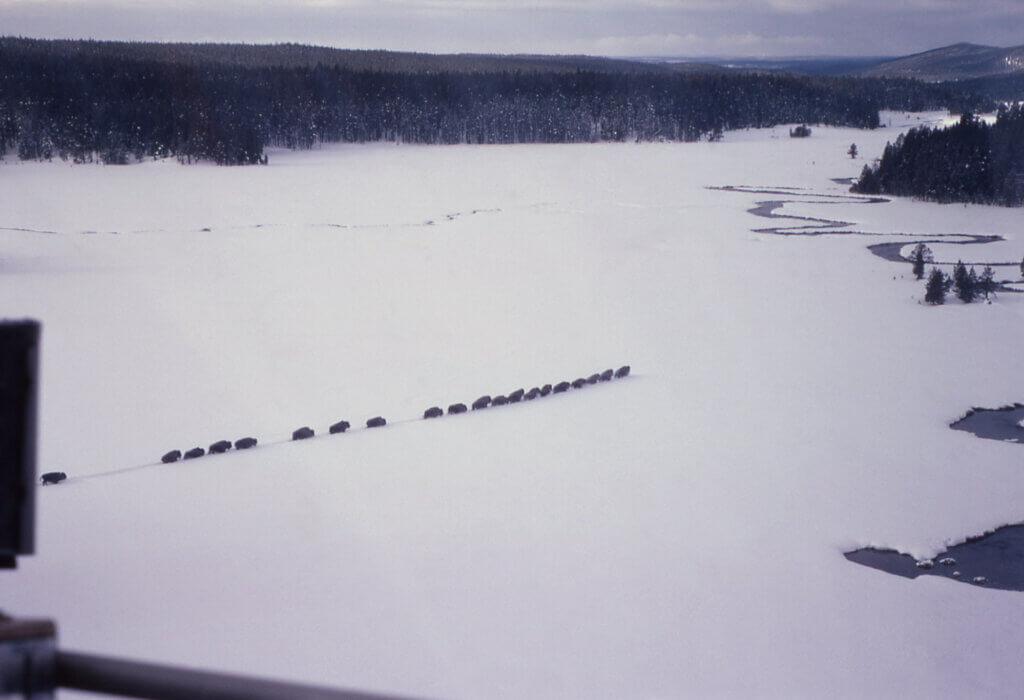

Coming together for signing the Buffalo Treaty on Blackfeet Territory in Montana Sept 23, 2014. Photo NPS by Keith Aune

The Buffalo Treaty is an agreement of cooperation, renewal and restoration of the ways that Native Americans envision the past and future with buffalo.

It is designed by Native American tribes to help create a national agenda that will return bison back to the land and allow them to roam freely between the United States and Canada.

The treaty originated when, following the advice of Elders, Blackfoot professors Leroy Little Bear and Amethyst First Rider of the University of Lethbridge envisioned a Buffalo Treaty and began to generate interest among the leaders of the InterTribal Buffalo Council.

Little Bear and First Rider organized a network of non-governmental organizations, corporations and others of the business and commercial community, to form partnerships with the signatories to bring about the manifestation of the intent of this treaty.

It took 10 years as a grassroots effort, designing the document, determining what to include and coordinating the network.

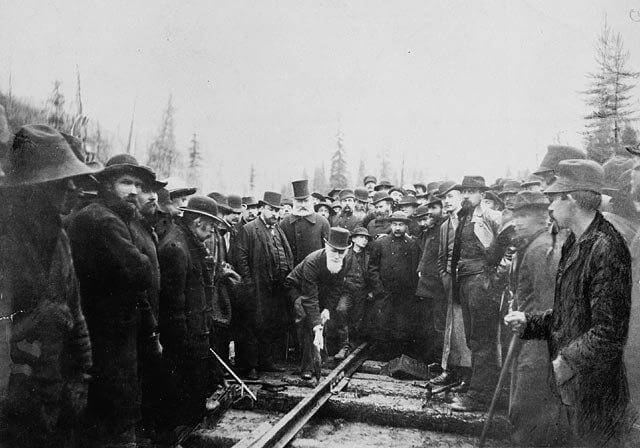

Then history was made. For the first time in 150 years, 13 nations from 8 reservations came together on Sept 23, 2014 and signed the first cross-border indigenous treaty on the Blackfeet Reservation in Montana.

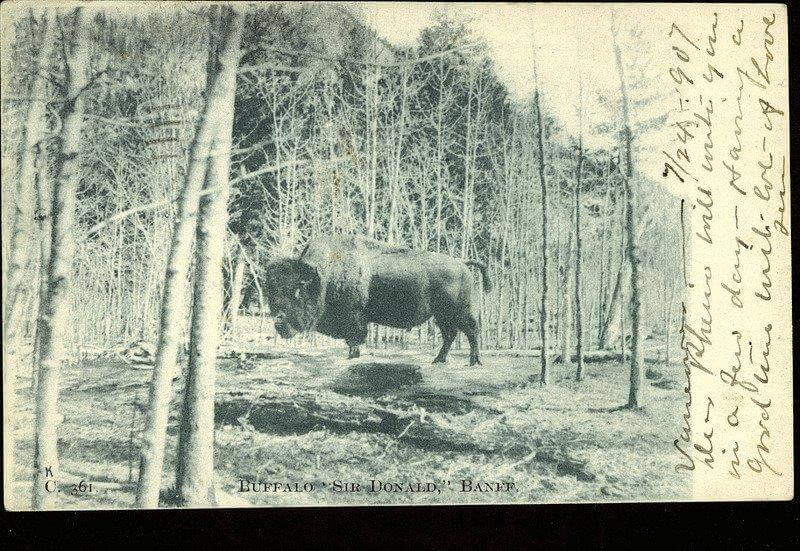

Four additional First Nations signed the treaty in Banff, Alberta the next year in August 2015.

This treaty, often referred to as the “Buffalo Treaty,” is an agreement of cooperation, renewal and restoration. It represents a significant step by indigenous people to preserve prairie ecosystems and their culture.

Since that time, hundreds of First Nations across North America have signed the Buffalo Treaty. To achieve the treaty’s vison, collaboration between researchers, governments and conservation groups is considered a must.

One of the most recent was when several First Nations from Canada and the U.S. came together at Wanuskewin in July 2023 to sign the Buffalo Treaty.

This treaty established an intertribal alliance to restore bison to 6.3 million acres of land between the United States and Canada—an area the size of Massachusetts!

Chief Daryl Watson of Mistawasis Nehiyawak first signed the treaty back in 2017. He asked, “How do we incorporate this knowledge and develop curricula’s around it so that our children have the ability to understand what the bison meant and what they’re going to mean in the future.”

James Holt from the Nez Perce Tribe in Idaho flew to Canada for the first time to make his mark and sign his name.

“It’s refreshing to see so many people from so many different walks of life come together for our love for buffalo,” Holt said.

It represents a significant step by indigenous people to preserve prairie ecosystems and their culture depending on restoration of the buffalo in both Canada and the US.

The treaty is aimed to help create a national agenda that will return bison back to the land and allow them to roam freely between the United States and Canada.

Initial signing of Buffalo Treaty with Blackfeet in Montana. Photo NPS by Keith Aune.

“Creator gave us many gifts and teachings to survive this world. One of those teachings is everything is interrelated. In the Indian practice, the interrelated world is realized through Treaty-making with all my relations.”

THE BUFFALO: A TREATY OF COOPERATION, RENEWAL AND RESTORATION 2014

Fort Battleford National Historic Site

RELATIONSHIP TO BUFFALO

Since time immemorial, hundreds of generations of the first peoples of the FIRST NATIONS of North America have come and gone since before and after the melting of the glaciers that covered North America. For those generations, BUFFALO has been our relative. BUFFALO is part of us and WE are part of BUFFALO culturally, materially and spiritually. Our on-going relationship is so close and so embodied in us that Buffalo is the essence of our holistic eco-cultural life-ways.

PURPOSE AND OBJECTIVE OF THE TREATY

To honor, recognize and revitalize the time immemorial relationship we have with BUFFALO, it is the collective intention of WE, the undersigned NATIONS, to welcome BUFFALO to once again live among us as CREATOR intended by doing everything within our means so WE and BUFFALO will once again live together to nurture each other culturally and spiritually. It is our collective intention to recognize BUFFALO as a wild free-ranging animal and as an important part of the ecological system; to provide a safe space and environment across our historic homelands, on both sides of the United States and the Canadian border, so together WE can have our brother, the BUFFALO, lead us in nurturing our land, plants and other animals to once again realize THE BUFFALO WAYS for our future generations.

PARTIES TO THE TREATY

WE, the undersigned, include but not limited to BLACKFEET NATION, BLOOD TRIBE, SIKSIKA NATION, PIIKANI NATION, THE ASSINIBOINE AND GROS VENTRE TRIBES OF FORT BELKNAP INDIAN RESERVATION, THE ASSINIBOINE AND SIOUX TRIBES OF FORT PECK INDIAN RESERVATION, THE SALISH AND KOOTENAI TRIBES OF THE CONFEDERATED SALISH AND KOOTENAI INDIAN RESERVATION, TSUUT’INA NATION, along with other nations.

ARTICLE I – CONSERVATION

Recognizing BUFFALO as a practitioner of conservation, WE, collectively, agree to: perpetuate conservation by respecting the interrelationship between us and ‘all our relations’ including animals, plants, and Mother Earth; to perpetuate and continue our spiritual ceremonies, sacred societies, sacred languages and sacred bundles to perpetuate and practice as a means to embody the thoughts and beliefs of ecological balance.

ARTICLE II – CULTURE

Realizing BUFFALO Ways as a foundation of our ways of life, We, collectively, agree to perpetuate all aspects of our respective cultures related to BUFFALO including customs, practices, harvesting, beliefs, songs and ceremonies.

ARTICLE III – ECONOMICS

Recognizing BUFFALO as the centerpiece of our traditional and modern economics, We, collectively, agree to perpetuate economic development revolving around BUFFALO in an environmentally responsible manner including food, crafts eco-tourism and other beneficial by-products arising out of BUFFALO’s gift to us.

ARTICLE IV – HEALTH

Taking into consideration all the social and health benefits of BUFFALO ecology, We, collectively, agree to perpetuate the health benefits of BUFFALO.

ARTICLE V – EDUCATION

Recognizing and continuing to embody all the teaching we have received from BUFFALO, We, collectively, agree to develop programs revolving around BUFFALO as a means of transferring intergenerational knowledge to the younger and future generations and sharing knowledge amongst our respective NATIONS.

ARTICLE VI – RESEARCH

Realizing that learning is a life-long process, We, collectively, agree to perpetuate knowledge-gathering and knowledge-sharing according to our customs and inherent authorities revolving around BUFFALO that do not violate our traditional ethical standards as a means to expand our knowledge base regarding the environment, wildlife, plan life and the role BUFFALO played in the history, spiritual, economic and social life of our NATIONS.

ARTICLE VII – ADHESION

North American Tribes and First Nations, and NATIONS, STATES, AND PROVINCES may become signatories to this treaty providing they agree to the terms of this treaty.

ARTICLE VIII – PARTNERSHIPS AND SUPPORTERS

WE, collectively, invited non-governmental organizations, corporations and others of the business and commercial community, to form partnership with the signatories to bring about the manifestation of the intent of this treaty. Organizations and Individuals may become signatories to this treaty as partners and supporters, providing they perpetuate the spirit and intent of this treaty.

ARTICLE IX – AMENDMENTS

The treaty may be amended from time-to-time by simple majority of the signatories.

SIGNATORIES AND RESOLUTIONS

Map, Resolutions and Official Letters

- Buffalo Treaty Map – High Resolution

- The Treaty – High Resolution image

- 2021 Letter from USA DOI office of the Secretary to Montana American Indian Caucus

- 2021 Letter from Montana American Indian Caucus to Secretary of Interior

- 2021 Canada Federal Minister of the Environment and Climate Change – Letter to the Buffalo Treaty

- 2021 Buffalo Treaty letter to Canada Minister of the Environment and Climate Change – finding ways and means to work together

- 2021 Buffalo Treaty letter to U.S. Secretary of Interior – DOI Bison Conservation Initiative

- 2020 Buffalo Treaty letter to Canada Minister of the Environment and Climate Change – Bison Conservation Initiative

- 2016 Buffalo Treaty all supporters Resolutions

- 2016 Buffalo Treaty Alberta Wildlife Bison letter and resolution signed

- 2016 Buffalo Treaty Badger Two Medicine letter and resolution signed

- 2016 Buffalo Treaty National Bison Range letter and resolution signed

2016 Buffalo Treaty Tunnel Mountain Name change letter and resolution signed

2016 Buffalo Treaty Yellowstone Bison Quarantine letter and resolution signed

What Signers of Buffalo Treaty Say

“I grew up without having a herd. As far as the cultural side, we missed the buffalo all these years and the younger kids were losing interest. But, with us getting the buffalo back now, I hear a lot of talk among themselves and that’s why we do it. We have to keep the culture alive, we have to keep the language alive and the buffalo has that spirit.”– Wyman Weed, Eastern Shoshone Tribe, Wind River

“The herd has grown. The work now is to create more space and make more of our lands available for them to exist on, and to grow a population to a sustainable level where we can begin harvesting them again. We can begin utilizing them in ceremonies, have an education program to work with our youth, bring our elders together with our young people, and to reinvigorate our language to learn about how we use all the parts of the buffalo. That’s part of the cultural revitalization. We are just glad to be part of this effort and to be with these other tribes that are working on bison conservation.” – Jason Baldes, Eastern Shoshone Tribe, Wind River

“Some of our creation stories are around the buffalo. I think it’s our time now as the two-leggeds help our four-legged silent nation, the buffalo nation, that was almost extinct. And to continue the teaching of our ancestors, our grandmas and grandpas and pass that on generation to generation. The more we help each other nation-to-nation, tribe-to-tribe, the more powerful we’re gonna be. The stronger voices we’re gonna have. The more relationships we’re gonna build.” – Ricky Grey Grass, Fifth Member Oglala Lakota Nation

“I’ve seen maps of the buffalo and how wide a range they used to have. But with this Buffalo Treaty, the two-legged have to do their part. We have the intelligence to be able to combat these things. A lot of it is storytelling – we have to compel people to try to understand.

“Back in the day, policies were put in place to eradicate us from our ceremonial, hunting and medicine grounds and that severed our connection to parts of the continent. Wherever the buffalo went, that’s where our territory is. But it took allies, it took people of compassion, people like yourselves, the allies and the NGOS that have seen something different, seeing that those policies are not good for their hearts…

“I think today with the Buffalo Treaty signers, they’re all allies together to find other options. We shouldn’t be treating the buffalo like livestock and trying to have so many restrictions on them. All they really want is their own place to go, they can take care of themselves. We used to be that way, we can’t be that way anymore because of our own fences that we’re stuck in too. We can’t go out and hunt or prepare for the winter.

“It kind of gives us hope if we can help the buffalo to be happier, more at peace and maybe that’ll help heal us. That’s the big message you hear with a lot of tribes—maybe if we can help them, it’ll help us.” – Mike Catches Enemy (Lakota name Sacred Thunder Buffalo), Oglala Lakota Nation

“We were established in 1992 and our mission was and is to return buffalo to tribal lands. Ideally, the way I see ITBC and the Buffalo Treaty working together is to heal across the land and bring the buffalo across the landscape. It’s a beginning and it’s a start to something new and better, for the buffalo and our future generations, not just us.” – Arnell Abold, Executive Director, Intertribal Buffalo Council

“The Buffalo Treaty is a testament to the agency and sovereignty of Indigenous nations. This international treaty unites diverse Nations and Tribes across North America by acknowledging the sacred relationship we have all had with the buffalo since time immemorial. The buffalo is our relative and our source of life. Nations recognize that by working together to restore and renew this relationship with our relative, we will grow stronger. Each year this treaty has welcomed new signatories and supporters. I am confident this momentum will continue to accelerate and that we will once again see the buffalo roam free on our homelands.” –

Marlene Poitras, Regional Chief, Assembly of First Nations Alberta Region

https://parks.canada.ca/lhn-nhs/sk/battleford/culture/Buffalo

Chief Isaac Laboucan-Avirom of Woodland Cree First Nation signs in 2019. Credit Edmonton Journal.

The college professors generally focused their efforts on increasing buffalo on tribal lands and to educate young people around bison culture.

Native tribes are being challenged to bring back and strengthen the Buffalo Culture as in the past.

The treaty commits the nations to ongoing dialogue and compelling advocacy for buffalo conservation, restoration and the reintroduction of buffalo to the grasslands.

At the same time, the treaty wisely leaves it up to each signatory to decide how to approach buffalo

and ecological restoration.

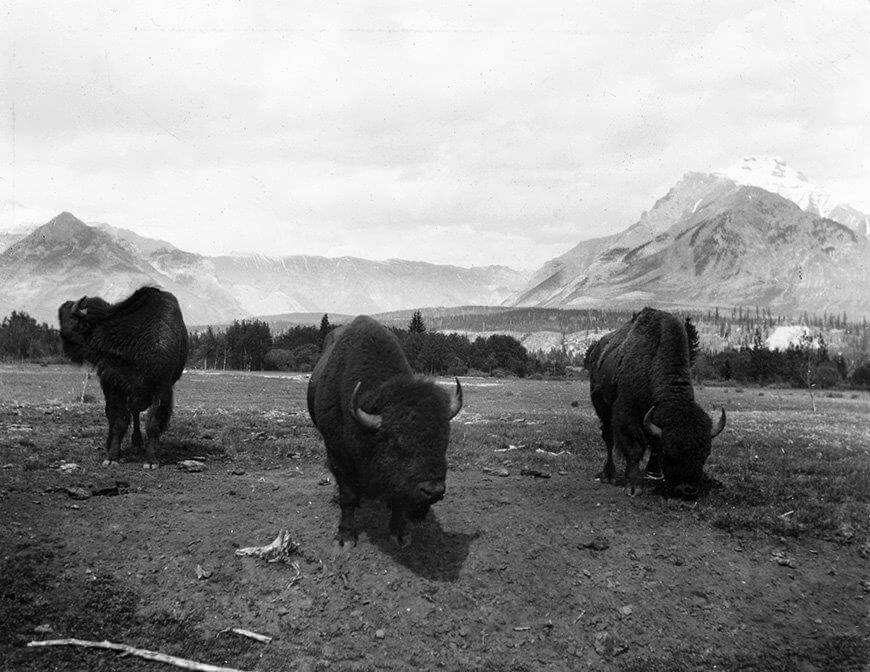

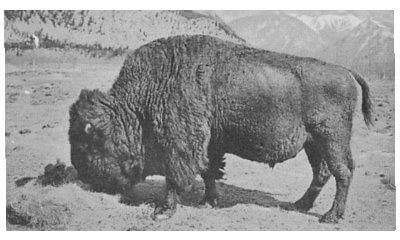

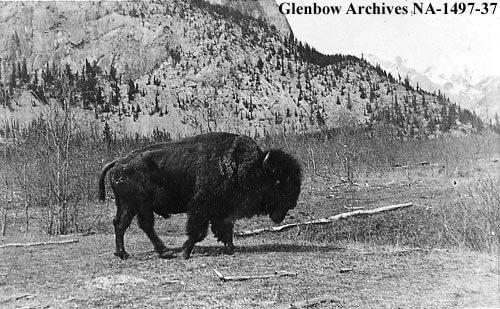

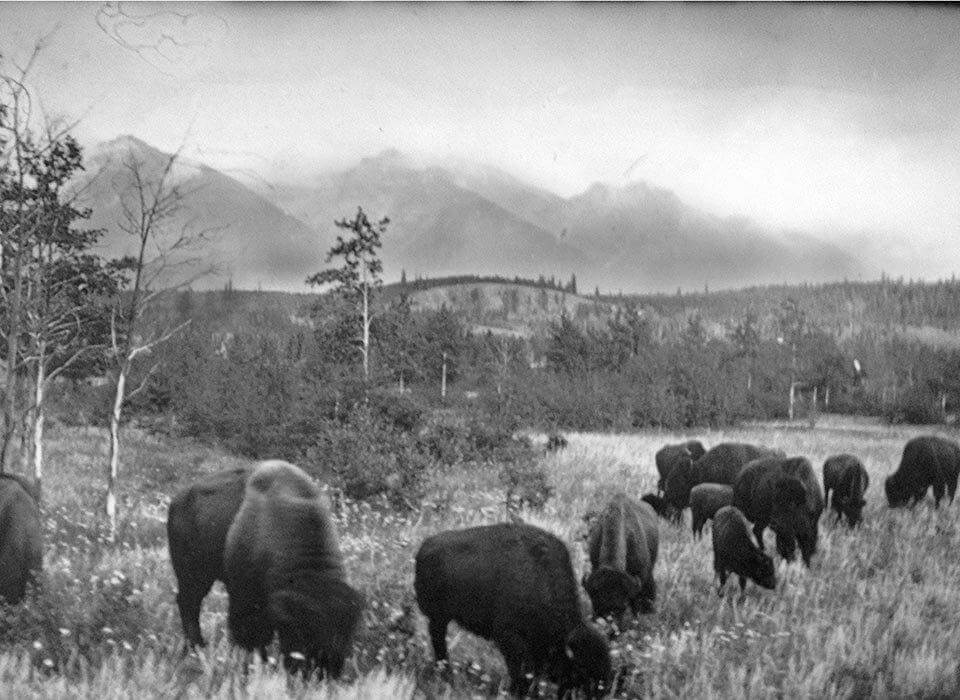

cows and calves from Elk Iland. Parks Canada

Honoring Relationships, Teaching Youth

There are so many great ideals in this treaty and we applaud them. Learning the old languages, songs and positive culture and customs. Teaching youth how to respect and take pride in their heritage and culture.

To honor, recognize and revitalize the time immemorial relationship tribal people have with BUFFALO, culturally, materially and spiritually. To perpetuate the health benefits of BUFFALO.

Continue economic development revolving around BUFFALO in an environmentally responsible manner including food, crafts eco-tourism and other beneficial by-products.

Perpetuate knowledge-gathering and knowledge-sharing according to their customs and inherent authorities revolving around BUFFALO that do not violate their traditional ethical standards.

‘Being environmentally responsible. Not violating ethical standards.’ Surely this means moving ahead with peaceful and positive attitudes and intentions—not glorifying anger, violence, bitterness, resentment, pain and other harmful or self-defeating activity.

However, some people also wonder if there might be negatives.

If the corridors for free movement of buffalo are established, will tribal buffalo migrate and perhaps never come back to the people who have nurtured and cared for them for so many years? Will Canada again be depleted of its Plains Buffalo? How can that be sorted out?

We wish them all the best in restoring the good things of traditional buffalo culture. If there are negatives, we would hope that the wiser heads will prevail. And any negatives that might better go by the wayside are avoided. Are there possible negatives here?

Of course we need to rise above the old cultures of warfare. Be accepting of all persons, rather than moving certain groups of people out of their homes as more powerful groups move in and force them out.

But we still see that happening.

Personally, I am mourning the deliberate breaking up of historic 5- and 6-generation neighborhoods and small towns by the American Prairie Reserve group in Montana, led by Silicon Valley consultants who aimed to “move fast and be nimble” in the manner of high-tech start-ups. And they did.

Their target is the Missouri River Breaks where I was born, where my family lived and loved, celebrated with friends and neighbors and survived through the terrible droughts of the 1920s and 1930s.

Now their lands are considered empty as these friends get pushed aside, their history, hard work and conservation projects obliterated from the face of a vast, empty wildlife playground for world-wide benefactors and “environmentalists.” (See my MT Blogs 8 and 17, June 23 and Oct 6, 2020.)

A pair of bulls graze near the Grande River in North Dakota. Photo courtesy of Vince Gunn.

Letters Attached to the Buffalo Treaty

Some of the letters attached to the Buffalo Treaty can strike fear in cattle-ranching families. For example, one letter comes from members of the Montana Legislature’s American Indian Caucus.

It asks Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, who is “the first Native American to serve as a cabinet secretary and other federal officials” to begin a dialogue with the Tribes to restore buffalo to public lands in general, as well as to the Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge in central Montana and Glacier National Park in northwest Montana.

“As Montana legislators and members of the Montana American Indian Caucus, we also urge you to take action to work with Montana Tribes to restore buffalo on public lands in the state,” says the American Indian Caucus letter.

Montana has a great deal of public lands. What of these 5-generation families who have worked hard to establish the recommended irrigation projects in the area? Who have sons and daughters ready and eager to take over their ranches?

The town of Malta, MT is losing its population of 2,000, say ranchers. They worry that each ranch lost to the community drains taxes from the county treasury, children from schools and business from stores.

The properties purchased by American Prairie Reserve are all strategically located near two federally protected areas: the 1.1 million-acre Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge and the 377,000-acre Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument. Other Federal and State lands intersect as well. Most of these lands are managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), a division of the Department of Interior (DOT).

Needless to say, cattle ranchers and many local townspeople—who have been watching the inevitable disintegration of formerly close communities, as one rancher after another sells out and families and businesses leave—are not pleased with what is happening.

Marko Manoukian, Phillips County Extension Agent of Malta, represents the Phillips County Livestock Association in presenting the cattle ranchers side of the Montana controversy over Prairie Reserve.

“They are crowding out the ability of ranchers to compete economically for agricultural land—in this case grazing land. Because they are a 501C3 charitable organization they get tax-free dollars to compete,” Manoukian says.

“Because American Prairie pays a premium for the property—more than a neighboring rancher could pay off with cows—this doesn’t allow for young people to come back and engage in livestock production.”

Who wins?

_____________________________________________

NEXT:_______________________________________

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog

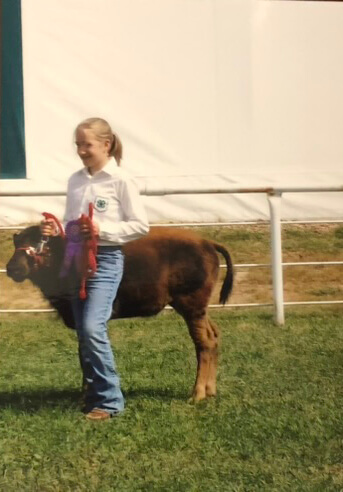

For achievement of this project, you may be required to prepare a display of your information depending on the individual project you have selected to do. This may be done using pictures, words or even demonstrations. Provincially, you are strongly encouraged to attend the Wild Rose Show and Sale held in Camrose. This show will provide all members the opportunity to meet other youth from across the province, and will teach you valuable skills needed in the industry.

For achievement of this project, you may be required to prepare a display of your information depending on the individual project you have selected to do. This may be done using pictures, words or even demonstrations. Provincially, you are strongly encouraged to attend the Wild Rose Show and Sale held in Camrose. This show will provide all members the opportunity to meet other youth from across the province, and will teach you valuable skills needed in the industry.