It’s a Girl! Bison Herd at Wanuskewin Heritage Park Welcomes New Member

bonus baby bison joined the herd at Wanuskewin Heritage Park, Saskatoon, in September 2021. Photo Wanuskewin Heritage Park

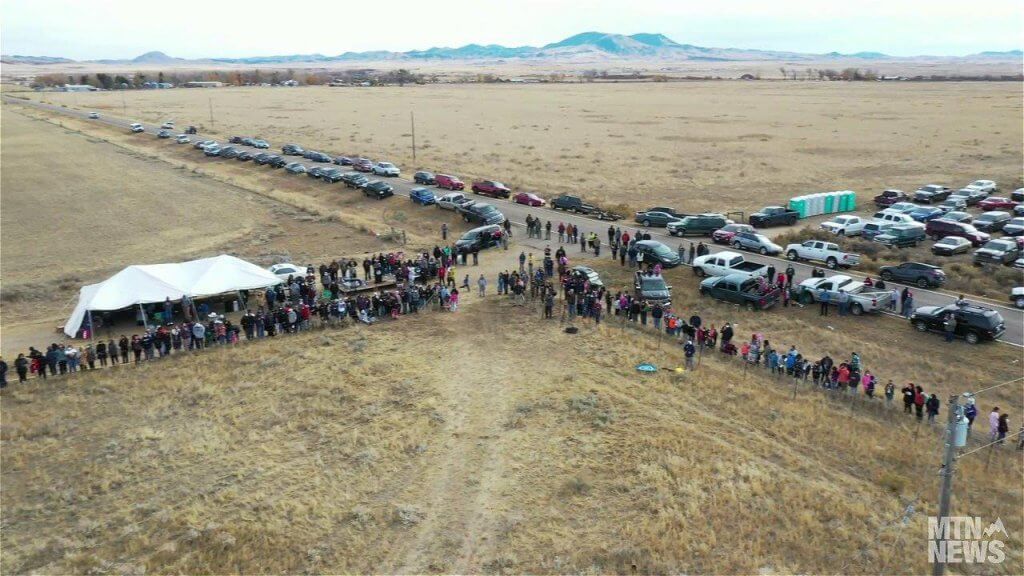

Wanuskewin Heritage Park welcomed back Plains buffalo on Jan 17, 2020 after nearly 150 years since bison grazed on the land where the Park now stands—on the outskirts of Saskatoon.

Elder Cy Standing of the Wahpeton Dakota Nation welcomed eleven plains bison to their ancestral home on the outskirts of Saskatoon.

A partnership—which includes Parks Canada, Wanuskewin and Yellowstone National Park in the U.S.—brought the animals back. They included six female calves from Grasslands National Park, four pregnant females and a mature bull from Yellowstone National Park.

“Bison almost became extinct. There were less than 1,000 animals in the late 1800s,” said University of Saskatchewan Prof. Ernest Walker.

The park’s chief executive officer said bringing in the animals could help in its bid to become a UNESCO World Heritage Site and will help provide world-class programming at the park.

“And the ability to draw people from all over the world to the park. Having a … species like the bison here is just a wonderful opportunity,” Darlene Brander said.

“I’m sure our elders from the early 1980s, wherever they are, are smiling. We did it. We came through for them 40 years later,” Walker added.

Wanuskewin received a $5-million donation from the Brownlee Family Foundation which is going towards the conservation effort and making sure the bison thrive.

The park’s leadership reported that it has been thinking about bringing the animals back to roam the area for decades, but funding and administrative hurdles proved to be difficult.

The park aims to have a herd of 50 bison after a number of years.

Fast forward to fall 2021. Much has been accomplished.

The herd has grown to 17. And, on September 12th, well past calving season, the ‘bonus baby’ bison girl was born–healthy and with a very protective mama!

Even more exciting, the site’s 19 dig sites though the hills and coulees have revealed tipi rings, stone cairns, pottery fragments, bones, a medicine wheel and other items. The excavations give a hint of the secrets of the bustling life that once dominated the area.

The repatriated herd now roams Wanuskewin’s expanse of historical lands and can be spotted by lucky visitors to the Park.

The growing lineage of these animals on this sacred land is the fruit of Parks Canada’s efforts to re-wild a selection of protected spaces across the country.

The bison can be viewed by passersby year-round on self-guided walking tours of the park and special event tours. They are a majestic reminder of the deep, historical significance of Wanuskewin.

Dating back 6000 years, the land was a meeting place for northern plains people from all around North America.

Archaeological finds, dating back to before the Egyptian pyramids, show that virtually every pre-contact cultural group in the Great Plains visited the area.

The reintroduction of plains bison to their ancestral home is a reflection of Wanuskewin’s deep and unique commitment ‘to be a living reminder of the peoples’ sacred relationship with the land.’

The arrival of a new calf is both a connection to the past and a living, breathing reminder of what is possible in the present.

Interpretive Centre at Wanuskewin Heritage Park. When walking the grounds visitors find themselves at the bottom of a steep cliff directly beneath dramatic peaks. They stand at the foot of the buffalo jump where thousands of plains bison were driven to their deaths over the span of centuries.

Visitors do not come to Wanuskewin just for informational plaques and stories of artifacts, though these things do exist in its state-of-the-art interpretive centre.

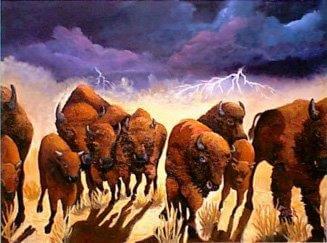

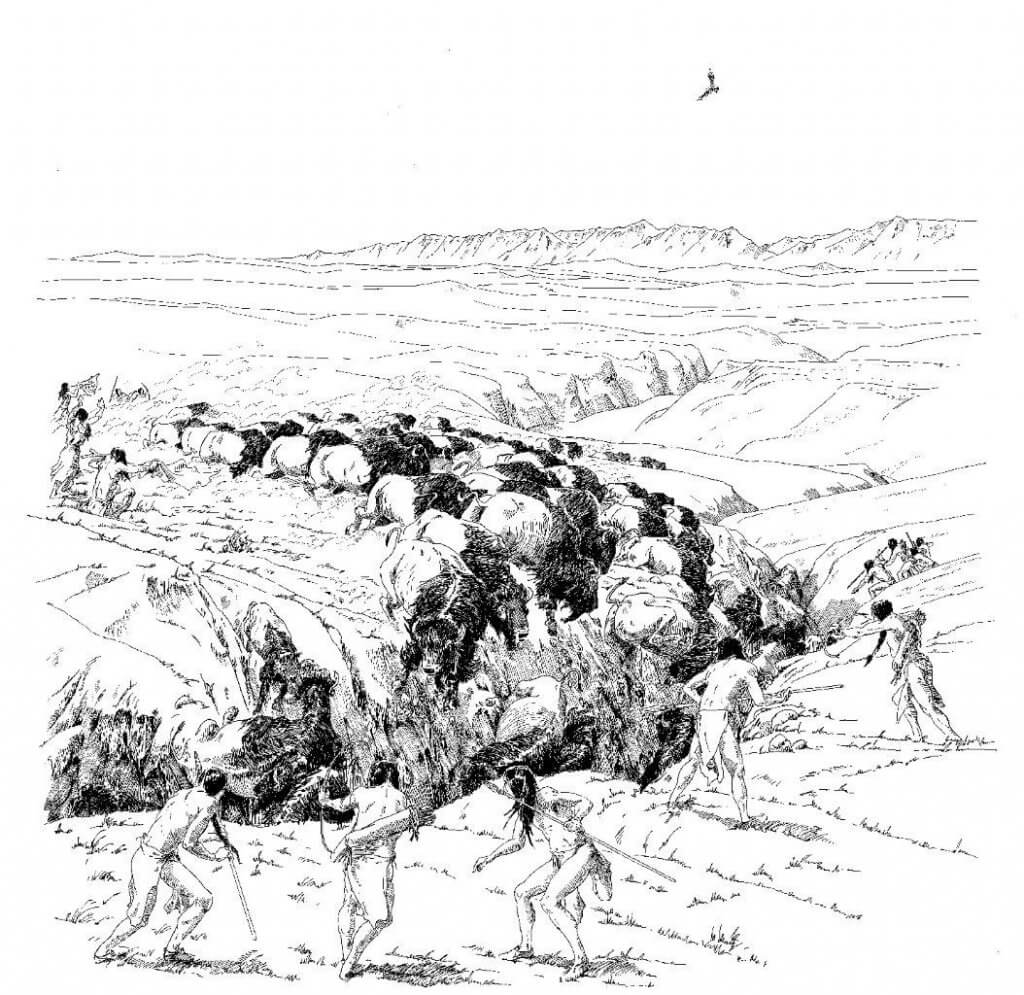

Rather, they are drawn into a land of subtle beauty that holds the remnants of a sacred, heart-stopping ritual—the buffalo hunt.

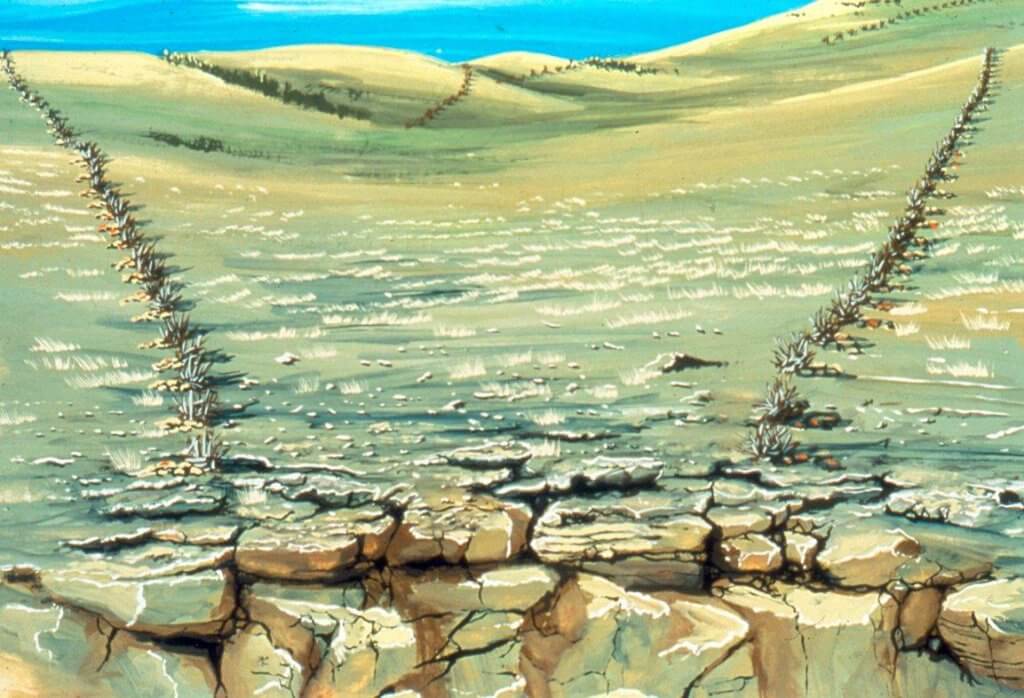

When walking the grounds of Wanuskewin, visitors will shortly find themselves at the bottom of a steep cliff directly beneath the dramatic peaks of the interpretive centre. True to the unassuming nature of the park, the land itself reveals nothing more than native plants and a green hillside.

But that exact spot is the foot of the ‘buffalo jump’ where hundreds if not thousands of plains bison were driven to their deaths over the span of centuries.

Truly the highlight of any visit to Wanusekwin is simply pausing at this spot and honoring the vision of stampeding animals and the people that used their hides, bones and flesh to survive.

2022 International Bison Conference in Saskatoon

The International Bison Conference will be held in Saskatoon July 12-15, 2022. Hosted by the Canadian Bison Association, in partnership with the Saskatchewan and US National Bison Associations. The convention is held in Canada every 10 years and will welcome close to 800 delegates who are stakeholders in the bison community including producers, chefs, consumers, researchers, conservationists, marketers and policy makers.

Get the details and register at https://bisonconvention2022.com/. Listen to inspirational speakers on bison history, conservation, research, marketing and the business of bison. Also, you will have the opportunity to visit local landmarks including Wanuskewin Heritage Park before, during, or after the convention. Learn, network and celebrate!

(Above news reported from Saskatoon Jan 17, 2020 to Oct 2021.)

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog