Eleven buffalo arrived at Wanuskewin Heritage Park in 2019. Eight months later they uncovered a petroglyph carved by human hands a thousand years ago in the paddock where they water. Photo credit Wanuskewin Heritage Park.

The rocks were discovered by Chief Archaeologist Ernest Walker, a professor at the University of Saskatchewan.

He remembers the exact date the discovery happened—Aug 16, 2020.

Walker immediately told Wanuskewin CEO Darlene Brander about the discovery.

“(Walker) knocked on the door and he knocked in a way that I knew something was up,” Brander recalls.

“He came in and said that, ‘We found it, we found rock art.’

“My eyes got kind of big,” Brander said.

Months before, they had been talking about what Wanuskewin really needed or would like to have. And that conversation led to one thing, she said.

“Wouldn’t it be great if we had rock art?”

Walker himself was stunned by the discovery.

He listed the other artifacts that have been discovered around Wanuskewin: bison jumps, tipi rings, buried campsites, projectile points, bones, bone and stone tools, charcoal, potsherds, seeds gaming pieces, personal adornments and the most northerly medicine wheel found on the plains.

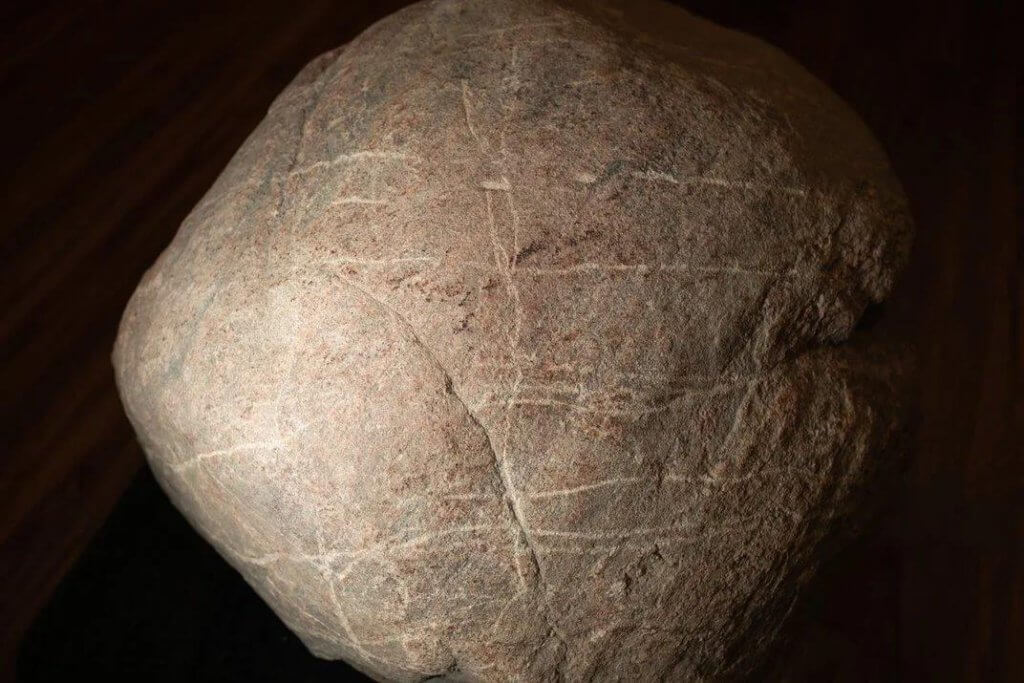

The first boulder was carved with parallel lines. “They’re a glimpse into somebody’s hopes and dreams,” said Ernie Walker who first identified the petroglyph. Credit WHP.

“What we didn’t have was rock art, and all of a sudden we’re in the rock art business.”

Both Ernie Walker and Darlene Brander made sure the next steps followed protocol and ceremony, which included consulting elders.

Rocks Fulfill an Indigenous Prophecy

The elders of the Wahpeton Dakota Nation had long prophesized that the return of Plains buffalo to their ancestral lands would portend a welcome turn of events for Canada’s First Nation peoples.

What they did not predict was that it would take just eight months after the buffalo’s arrival for this prophesy to come true.

“The elders used to tell us ‘When the bison come back, that’s when there’ll be a good change in our history,’ ” says Wahpeton Dakota Elder Cy Standing.

“We’ve been down a long time. But it feels like we are starting the way up.”

The elders called the rocks “grandfathers.”

After some discussion with them, Brander said the elders granted Wanuskewin permission to move some of them onto the site ‘so that we could share them with the world.’

She said elders and knowledge keepers were surprised and thoughtful about the discovery.

“There are no manuals that come with the petroglyphs, so really it lends itself to contemplation and thinking about spirituality and the role in culture within the different cultures within the Indigenous communities,” Brander explained.

“To see the elders experiencing that was really special.”

Indigenous peoples have a complicated relationship with traditional archaeologists.

Excavations have often been compromised by strangers who arrive, dig into important places without permission and steal sacred objects.

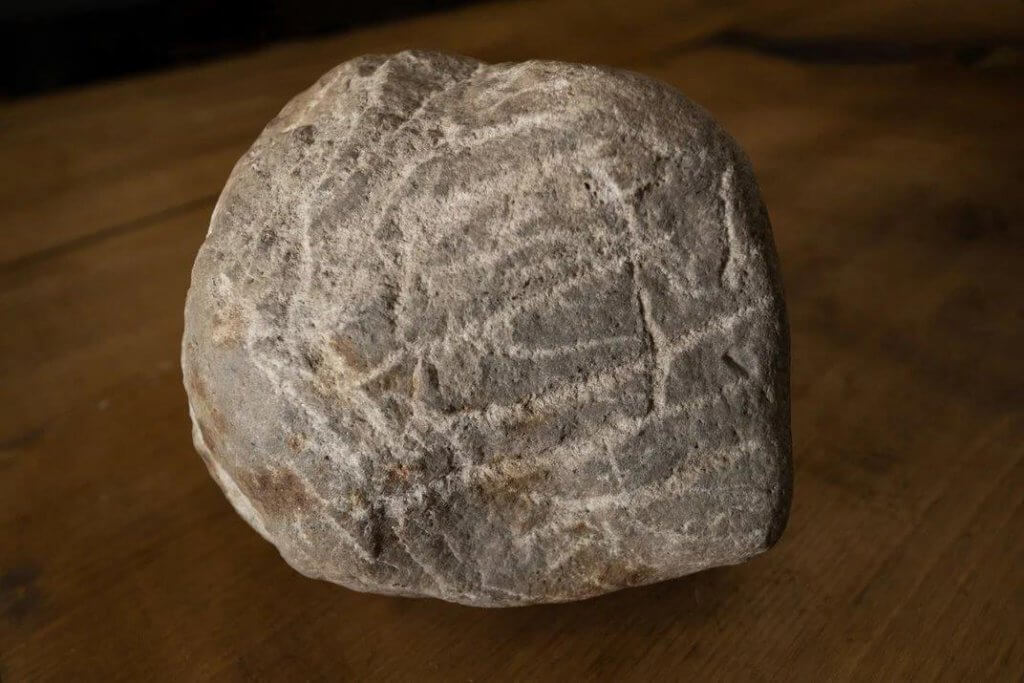

Days after the first discovery, Walker and his team found three more petroglyphs and the stone knife used to make the carvings. He says he thinks these discoveries are a sign the buffalo “are happy to be here.” WHP.

But after being offered a role in Wanuskewin’s development and management, the elders saw this as an opportunity to reclaim their history for their children—and share it with non-Indigenous people.

“When you come here, you can feel the energy,” says Cy Standing.

He had joined the team with Wanuskewin’s first elders and recalls attending sweat-lodge ceremonies and other events during the park’s development.

“We asked for direction and guidance [from the ancestors],” he said.

The park, which ‘was a gathering, healing and ceremonial place,’ had the potential to reconnect Indigenous people with each other, their culture, the land and the bison.

“Bison [are] very sacred to us, and in our stories we call them our brothers,” adds Standing.

The stone knife used to carve the newly discovered petroglyphs was found buried nearby, 10 centimetres below the surface. WHP.

Everything about Wanuskewin centers on the plains bison.

But for the park’s first 35 years, the animals only existed in oral history and as bones and artifacts recovered from the park’s 19 pre–European contact archaeological sites in the area.

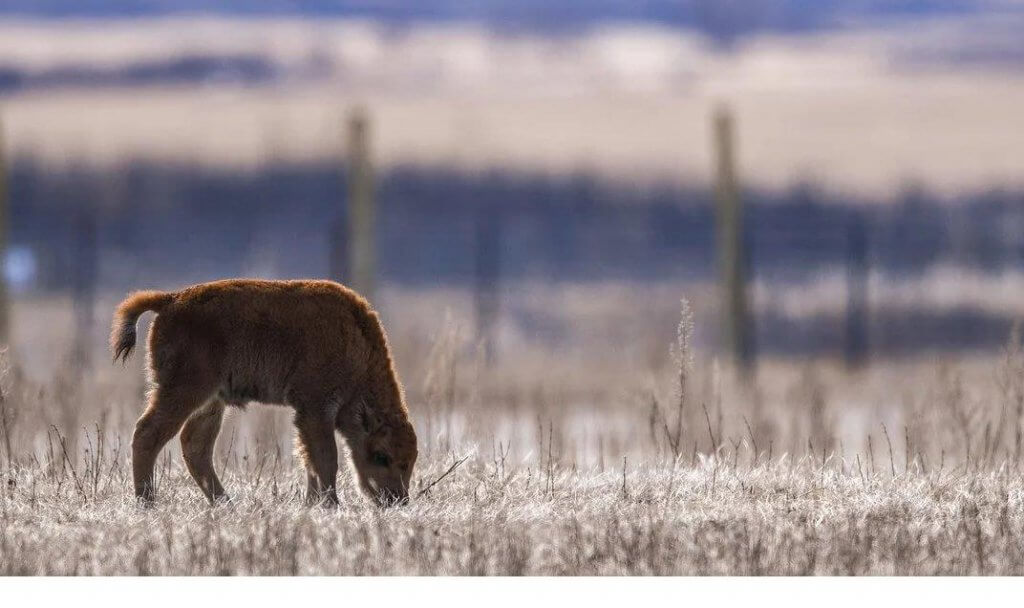

Then in 2019, as part of a $40 million dollar expansion, six female calves were brought in from Grasslands National Park to help establish the buffalo herd at Wanuskewin, as well as four pregnant females and a mature bull from Yellowstone National Park.

Only months after the 11 buffalo arrived—after almost 40 years of human-led archaeological excavations—the bison unearthed the park’s first petroglyphs.

“We’d found the detritus of everyday living: broken stone tools and debris from the manufacture of stone tools. Things like that,” Walker says.

“But [we] didn’t find ideas. [We] didn’t find emotions. The petroglyphs brought that. They’re that other dimension. … They’re a glimpse into somebody’s hopes and dreams.”

Staff invited park elders in to see the petroglyphs and offer advice on spiritual guidance and a management plan for the boulders.

Though the First Nations believe that all rocks are sacred and shouldn’t be moved, in this case, the elders felt that moving the boulders to protect them and to share them with the world would be acceptable, says Standing.

In Indigenous culture, the hoofprint tradition revolves around the feminine, fertility and renewal.

Pointing to a little tailed spirit figure in the center of the ribstone, as the first stone was called, Walker says the surface of the rock acts like a curtain or a screen between the physical and supernatural.

He adds, “The little figure’s tail is going into the crack in the rock. It’s meant to portray a passage from this world to the supernatural world.”

Like Walker, Standing acknowledges the fortuitous nature of the bison’s discovery of the petroglyphs.

Cy Standing says the petroglyphs help tell Native people—and especially children—about the good life they had when there were great herds of buffalo running free. He suggests that knowing this can help them move ahead. WHP.

“You know, we don’t really know our history. We have oral history,” he says, “but all the books were written after contact. [The petroglyphs] show us more.

He wants people to understand that the petroglyphs come from thousands of years ago, when the Native people were living well and cared for themselves and their tribe without outside help.

“We had a good life. Our children need to know that so they can go forward.”

Walker’s Discovery in the Paddock

Archaeologist Ernie Walker and bison manager Craig Thoms made the find last summer while visiting the park.

They were out feeding the bison at the paddock. Standing near a wallow—a bare spot where the buffalo give themselves dust baths—about 800 meters west of the Wanuskewin building.

Walker looked down at the ground where the bison had been rolling and noticed a grooved rock protruding through the dirt, according to Laura Woodward, reporting on CTV News Saskatoon, Nov. 19, 2021.

“I just happened to look down at my feet and there was a boulder protruding, partly protruding, through the ground and it had a kind of strange groove over the top of it,” Walker recalled.

He said at the time he thought the groove may have just been damage. Assuming the cut was from tool damage, he brushed away the dirt, only to expose another groove and then another.

“They were all parallel, all symmetrical,” he says.

Walker brushed at the grooves.

Carvings on the petroglyphs are dated at between 300 and 1,800 years ago, with a probable age of around 1,000 years old. WHP.

“I was trying not to have a heart attack because I hadn’t expected it,” Walker told reporters at the rock unveiling.

“It was at that point I realized this [was] actually what is known as a petroglyph. This was intentionally carved.”

“The interesting thing is the bison were the ones that actually partially uncovered it because we’re in their paddock, where they water. They have to pass through this paddock going from one pasture to another.

“So they do spend quite a bit of time there. They will wallow. They will give themselves dust baths, and they had denuded most of the vegetation.

“They were responsible for showing us these buried boulders,” Walker added.

“They’re just very happy to be here.”

The ribstone is currently on display at the park’s interpretive center.

The park received a letter from the Saskatchewan Archaeological Society—after submitting their findings—which attests that the carvings on the rocks are indeed the result of cultural modification.

“The placement and alignment of the carved images could not be created any other way,” executive director of the Archaeological Society Tomasin Playford wrote.

Brander said this was an extra layer of verification that supported Walker’s expertise.

She said this kind of support is really important for the park’s UNESCO World Heritage designation.

The park was named to the tentative list in 2017 and is still awaiting official designation.

She said that if it was anyone else who came across the rock the day Walker did, they may have just walked on by.

Brander calls the petroglyphs the final piece that makes Wanuskewin unique in the world.

Some of the petroglyphs they found were large boulders; others smaller rocks. WHP.

Walker says the carving resembles the bones of a bison and represents fertility.

He believes Indigenous people carved the rock more than a thousand years ago.

He had surveyed the area in the 1980s and didn’t find anything. Not until the bison themselves brought it to the surface.

“They uncovered it, just with their normal activity,” Walker says.

Is this a sign the buffalo like living here?

Walker thinks so.

“I like to think it’s their message that they’re happy to be here.”

Days after the first ribstone discovery, Walker and his team found three more petroglyphs.

To their surprise, they also found the tool used to make the carvings. A stone knife was found adjacent to it about 10 centimetres below the surface.

“This is a stone tool, no question. It had been used and re-sharpened.

“When I measured the width of the cutting edge of the stone knife, it’s the same width as the grooves on the rock,” Walker said.

“This is tremendously significant and very unusual,” Walker says of finding the knife.

The archaeologist says it is rare to find the carving tool.

“You never get that,” he says.

“Whoever did that, left it there or misplaced it, probably over a thousand years ago. I like to think it’s their business card. They left their business card here.”

“It’s significant and monumental,” Brander says.

The petroglyphs and carving tool are secured in glass, on display in the park’s building.

Petroglyphs are carvings, engravings or incisions into a rock, Walker explained.

He said rock art can be found around the world and in the northern plains. There are about nine different styles.

Walker said the four petroglyphs found are carved in the hoofprint tradition, most common in southern Alberta, southern Saskatchewan, North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana and Wyoming.

It’s called hoofprint because instead of engraving a whole bison onto a rock, which would take a lot of work, Indigenous Peoples engraved just the split hooves, Walker said.

“So it’s very metaphorical. Those hooves represent a bison.”

From ethnographic information, Walker said there are three things involved with the hoofprint tradition: femaleness, fertility, and renewal.

“And it has to do with bison. It’s about the sacred relationship between females and bison.”

From the spot where the petroglyphs were found, it’s a straight, 380 yards across the Saskatchewan grassland to the edge of some of the steepest cliffs that line the park’s Opimihaw Creek valley.

Formed about 7,000 years ago—after the recession of the Wisconsin glacier—the 130- to 160-foot drop from the edge of the surrounding prairie to the valley bottom was identified by nomadic Indigenous peoples as an ideal buffalo jump once used in hunting.

The site attracted almost every pre–European contact group in the region.

For thousands of years, Blackfoot, Cree, Ojibwa, Assiniboine, Nakota and Dakota people following the migrating bison found food and shelter at the fertile confluence of the South Saskatchewan River and Opimihaw Creek.

They left behind ample evidence of habitation and—after Europeans and Métis arrived in the region as part of the fur trade in the 1860s—metal implements such as gun cartridges and a strike light.

“Everybody was here at some point,” says Walker of the site’s almost continuous, 6,000-year occupation.

Then came Treaty Six, an 1876 agreement between the English crown and Indigenous representatives that opened up the land for white settlement by promising every Indigenous family of five one square mile of land.

After its passage, First Nations people were, ‘of course . . . moved off to reserves’ away from their traditional nomadic migration routes, Walker adds.

Around that same time, hunting decimated the bison population, leaving no wild bison in Canada by 1888, according to the Wildlife Conservation Society.

With the bison and people gone, the land that now forms the park became a small, private ranch and homestead owned by white settlers.

These new residents first received a sign that the property was home to something special in the 1930s, when a medicine wheel, a healing landmark consisting of a central stone cairn and an outer ring of rocks, as well as multiple smaller cairns, was rediscovered.

Bison Return after More than 100 years

It has been nearly 150 years since Plains bison have grazed on the land where Wanuskewin Heritage Park now stands.

The buffalo brought in from Grasslands National Park and Yellowstone National Park involved a partnership—between Parks Canada, Wanuskewin and Yellowstone National Park in the US.

All the buffalo have pure Plains bison genes and will replicate the species that once roamed the Prairies, according to Kyle Benning of the local Global News on Jan 17, 2020.

“Bison almost became extinct. There were less than 1,000 animals in the late 1800s. They’ve come back, but of course, there are questions of genetic purity and all these sorts of things,” said Walker.

Wanuskewin said the grasslands of North America are among the most endangered biomes in the world, and by bringing bison back into the fold, they will be able to restore native grasses and hopefully re-establish the species.

The park’s chief executive officer said bringing in the animals could help in its bid to become a UNESCO World Heritage Site and will help provide world-class programming at the park.

“And the ability to draw people from all over the world to the park. Having a … species like the bison here is just a wonderful opportunity,” Darlene Brander said.

Wanuskewin also received a $5-million donation from the Brownlee Family Foundation which is going towards the conservation effort and making sure the bison thrive.

The park’s leadership said it has been thinking about bringing the animals back to roam the area for decades, but funding and administrative hurdles proved to be difficult.

“I’m sure our elders from the early 1980s, wherever they are, are smiling. We did it. We came through for them 40 years later,” Walker added.

The plan is to eventually have a herd of 50 bison in Wanuskewin Park.

Discovery of Carving Promotes UNESCO Angle

The park’s chief executive officer Darlene Brander said bringing bison to the site could help in its bid to become a UNESCO World Heritage Site and will help provide world-class programming at the park.

Wanuskewin is in the process of getting recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

New baby bison born to a cow from Yellowstone National Park grazes contentedly in a field at Wanuskewin Heritage Park. WHP.

With the rare discovery of the petroglyphs, Brander says Wanuskewin is one step closer to reaching the designation.

“It’s significant and monumental,” Brander says.

She says petroglyphs were the missing puzzle piece in their UNESCO application.

The petroglyphs and carving tool are secured in glass, on display in the park’s building.

Verification of each step is also important for the park’s UNESCO World Heritage designation.

The park was named to the tentative list in 2017 and is still awaiting official recognition.

There are 20 World Heritage sites in Canada. None of them in Saskatchewan.

The first hint that this place was home to something special came in the 1930s, when a medicine wheel, a healing landmark consisting of a central stone cairn and an outer ring of rocks, as well as multiple smaller cairns, was researched.

“The story goes that professors from the University of Saskatchewan used to come out and have tea parties on Sunday afternoons at the medicine wheel,” Walker says.

An archaeological dig in 1946 and another small excavation in 1965 followed, but it wasn’t until the 1980s that the land’s archaeological wealth was recognized and a serendipitous series of events saved the site from being developed into condos.

As Walker and the park’s other founders sought funding and made plans in the early 1980s, they realized that a heritage park focusing on First Nations culture and history needed to include First Nations people in the planning.

Walker reached out to a friend, the late Hilliard McNab, an elder from George Gordon First Nation, for guidance.

“He said, ‘This place wants to tell its story,’” the archaeologist recalls.

McNab helped find other elders who wanted to be involved in the project and the archaeologists reached out to them as well.

Brander says the petroglyphs are the final piece that makes Wanuskewin unique in the world.

Wanuskewin hopes to become a UNESCO World Heritage site by 2025.

______________________________________________________________________________

NEXT: Bison in Theodore Roosevelt National Park

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog