At the center of the Northern Plains is a rugged section of Badlands, buttes and fertile grasslands, where buffalo, cattle and sheep graze, and deer and antelope still roam.

Please join us on the 10-site tour we’ve put together of the last great hunts and other historic and contemporary buffalo events, each clearly marked by a yellow sign.

After the miracle when the last great buffalo herd of 50,000 returned here to the relative safety of the Great Sioux Reservation in the fall of 1880 they survived here for nearly three years before being killed off, mostly in traditional Native American hunts.

These included the winter hunt in the Slim Buttes of the Duprees, theHiddenwook Hunt, and the valley of the last stand—the final harvest of the last 1,200 wild buffalo by Sitting Bull and his band on October 12 and 13, 1883.

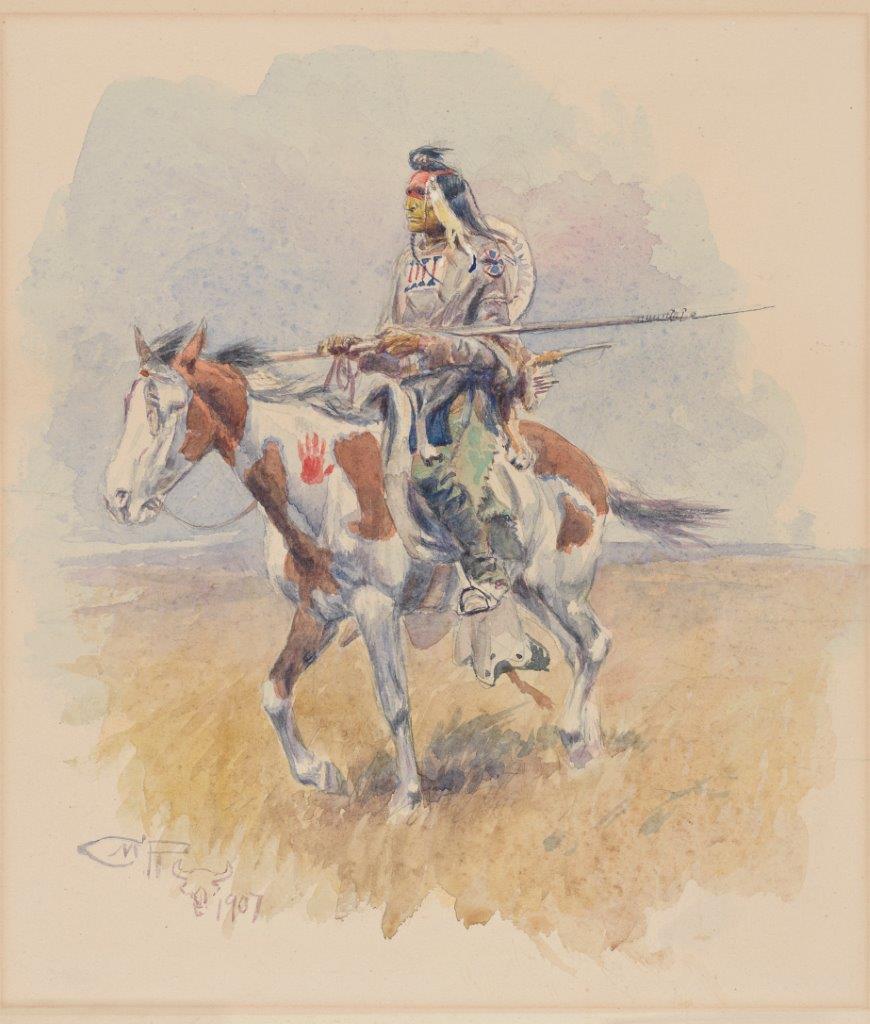

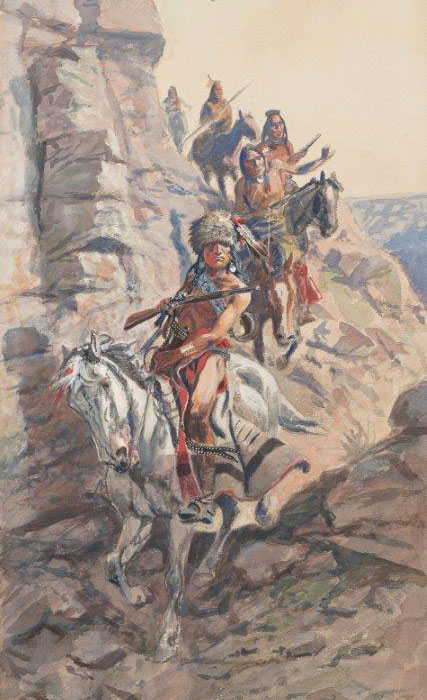

The Self-Guided Tour includes three of the Last Great Buffalo Hunts including the final harvest of 1,200 buffalo by the Sitting Bull band in 1883. Painting by CMRussell, Amon Carter Museum.

At the center of these events are previously untold stories and authentic, unspoiled places to envision where they took place.

This region, bordered by the North Dakota towns of Hettinger, Reeder and Scranton, and the South Dakota towns of Lemmon, Bison and Buffalo, is where Native people conducted the last traditional hunts of the majestic wild buffalo that once roamed here in huge herds on what was then the Great Sioux Reservation.

The history of the last buffalo hunts you’ll find here is true and documented from primary sources. Although not widely known until recently, it is told in detail by people who were there on those hunts.

They are traditional Native American hunts that somehow fell through the cracks of U.S. history.

Often showcased is the shameful history of the buffalo’s final days as a wasteful slaughter by white hide hunters.

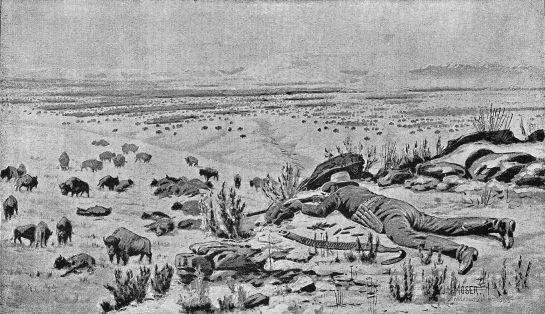

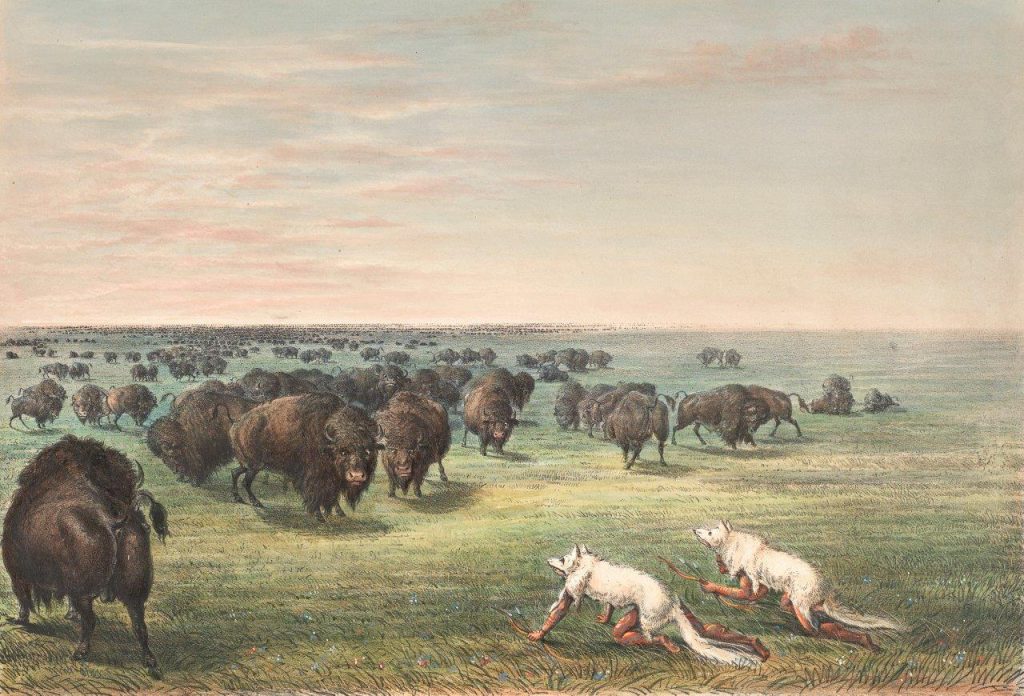

White hide hunters slaughtered huge numbers of buffalo with powerful guns, in what was called a stand—often a single shooter hidden from sight, killing any leader that attempted to run. Illustration from Wm. Hornaday’s 1889 book “The Extermination of the American Bison.”

That happened, of course. But it is not the whole story.

Instead, the first-person recollections from these final hunts bring together a heroic saga befitting the noble beasts themselves.

It features Native Americans, who followed time-honored religious traditions in planning and preparing for each hunt, following through, caring for the meat—and never failing to give thanks for their success.

And then, just before the last wild herds disappeared forever, the Duprees, one local Native American family returned to the hunt site to save 5 orphaned buffalo calves—and became internationally famous for nourishing their own herd.

Included on the tour are Prairie Thunder, a full-size mounted buffalo at the Dakota Buttes museum, and an authentic buffalo jump at Shadehill, S.D, used for thousands of years—long before hunters had the luxury of horses and guns.

In no other place in the world can you find the history of all these events brought together.

Here all parts of the Buffalo story come together. From ancient times until now, when nearly every Indian Tribe in the Plains owns their own tribal buffalo herd and are delighted to share it with you.

Visitors can plan their Buffalo Trails jaunt from anywhere in the world via online connections.

So if you’re a traveler smitten by the iconic American buffalo, you can plan your next trip around buffalo sites you find here and on our website. We outline world class trips to visit buffalo-related sites, both historic and modern day.

North Dakota Tourism has added our Buffalo Trails Tour to its Best Places and pitches it with international tours. South Dakota Travel provides links as well. (This information is available in our Self-Tour Guide “Buffalo Trails in the Dakota Buttes” available at local businesses and hettingernd.com/buffalotrails.)

Site 5. Saving Five Calves

This may well be the area where Pete Dupree and his family came with a buckboard wagon to capture buffalo calves. Although we don’t know the precise details, likely it happened in 1881, the next summer after their Slim Buttes hunt.

The Dupree party likely came over the ridge at the left in a buckboard wagon from their homes on Cherry Creek, and perhaps discovered a band of buffalo resting under the shade of the cottonwoods and cooling off in the shallow waters of the Grand River. Photo FM Berg.

As cattle ranchers, they no doubt looked for young calves they could catch and handle, but strong enough to survive the trauma of being adopted by reluctant range cows.

Imagine the Duprees coming from the southeast—center left—from their homes on Cherry Creek at the Cheyenne River.

Their small party must have included the wagon and several Lakota horseback riders, perhaps leading extra horses for packing fresh meat home. They travelled about 50 to 60 miles to the first buffalo herds—a two-day trip with the wagon—and not far from today’s town of Dupree, named for the family.

Methods of catching calves varied, as described in several sources. When buffalo stampeded from hunters, a number of calves usually fell behind and could be tamed. Or hunters could shoot cows and rope the calves that milled around their carcasses.

Young calves often came willingly to their captors. It was said a hunter might walk up to a buffalo calf and put two or three fingers in its mouth. After it sucked, the calf followed happily wherever he went.

Sometimes they followed a rider on horseback.

Young calves could be easy to catch when they fell behind the herd. Photo courtesy of South Dakota Game Fish and Parks.

Charles Goodnight, Texas rancher, said if he chased a herd of buffalo, young calves soon tired and fell behind. Then if he changed course and turned aside, the calves followed his horse rather than the herd. One day three buffalo calves followed him all the way to his ranch.

Not so, older calves. They sometimes fought so ferociously when roped that they fell dead. Many other captured calves died before they got the nourishment they needed.

The Duprees must have done things right to avoid the typically high death loss of orphan buffalo calves. They found range cows to mother the young calves, despite the challenge of coaxing wary range cows to accept the strange-smelling calves—and the lanky youngsters to nurse the low-slung cows.

The Duprees in their buckboard likely had outriders and pack horses along to carry fresh meat home for their several families. CM Russell painting, ACM.

But once bonded the five buffalo calves apparently followed their new mothers happily, grazing together on reservation lands with the Dupree cattle. Later they may have added more calves.

By 1888 Pete Dupree owned 16 buffalo. When he died in 1898, his herd had increased to more than 80.

Fortunately, his brother-in-law found a willing buyer in Scotty Philip of Fort Pierre, who ran thousands of cattle with his wife Sarah “Sally” on her reservation allotment—as a Lakota and French woman.

Phillip sent six cowboys to round up the Dupree herd and drive them the hundred miles to his fenced pasture. His nephew George wrote of the formidable task of chasing nearly wild buffalo, but they finally brought in 83 through the pasture gate.

By this time American buffalo were nearly extinct as a species. William Hornaday had made his official count of the surviving buffalo in a report to the Smithsonian Museum in 1887, as published in his book The Extermination of the American Bison, two years later.

His careful tally listed only 1,091 head for all of North America, with the largest herd being 200 in Yellowstone Park. Barely over 500 lived in the U.S., and he added 550 as “very old rumors” of buffalo in Canada.

The “bottleneck,” as it’s been called—came in the 1890’s, or perhaps a bit later, around the turn of the century when the “safe and protected” Yellowstone Park herd of around 200 was decimated by poachers.

The narrow bottleneck nearly closed off completely then. It could have happened. The American buffalo could have died out forever.

“There is no reason to hope that a single wild and unprotected individual will remain alive ten years hence,” Hornaday wrote in despair. “The nearer the species approaches complete extermination, the more eagerly are the wretched fugitives pursued to the death whenever found.”

Yet, amazingly, buffalo made it through the bottleneck and were saved from extinction.

“The buffalo were saved because a handful of men captured a few wild buffalo and raised them in captivity during the 1880s and 1890s,” writes David A. Dary in “The Buffalo Book.”

Five groups and families are honored as pivotal in saving the buffalo. They are the Pete Dupree and James “Scotty” Philip families in South Dakota; Samuel Walking Coyote and his herd purchasers Charles Allard and Michel Pablo in western Montana; James McKay and neighbors of Manitoba, Canada; the Charles Goodnights of Texas, and C.J. “Buffalo” Jones of Kansas.

Three of the five had Native American roots and knew well the cultural importance of buffalo in the lives of their people. The Dupree and Philip families, the Walking Coyotes and Allard and Pablo, and McKay, a Métis, all held a personal stake in buffalo survival. Rather than butchering or selling the increase, they tended to grow their herds, multiplying and strengthening their numbers. They valued the natural wild traits of the buffalo without trying to alter them.

The other two, the Goodnights of Texas and Buffalo Jones of Kansas, respected the natural world, cherished their buffalo and their own roles in preserving them.

However, more than the others, perhaps, both hoped to reap economic rewards, and engaged in considerable buying and selling. Also, both experimented with unsuccessful cross-breeding with cattle in the hope of developing hardier, more productive beef animals.

Likely others helped to save the buffalo, yet these families made special efforts to rescue and raise buffalo calves and kept sustainable adult herds for many years. Their herds flourished and eventually became the foundation for buffalo herds throughout the United States and Canada.

While men received most of the credit from early historians, women were much involved in saving the buffalo, as well. Native American women went on all the big hunts, watched the great herds disappear under the ruthless slaughter by commercial white hunters with their powerful, long-range rifles and called for saving them.

Ranch women, both Indian and white, likely helped the fragile calves to survive and thrive.

“Mary Ann Good Elk Dupree and Sarah Philip were unsung heroines in the saga, largely ignored by historians but credited by their families for their roles,” wrote Pat Springer in the Oct. 12, 2009, Rapid City Journal. “Both women were Lakota, for whom the buffalo are sacred. And both, according to their descendants, helped persuade their husbands to rescue buffalo for their preservation.”

Scotty Philip grew his buffalo herd to as many as a thousand. On the Missouri River bluffs west of Pierre his buffalo became a well-known tourist attraction. When he died in 1911, it took his sons 15 years to sell them. Many went to parks and wildlife sanctuaries in South Dakota and throughout the country as well as to private individuals.

History rightly gives the Duprees and Philips, the Walking Coyotes with Pablo and Allard, McKay, Goodnights and Jones a great deal of credit for saving the buffalo.

Also honored for this distinction are the visionary conservationists—William Hornaday, President Theodore Roosevelt, and George Bird Grinnell—who fought for buffalo sanctuaries and laws to protect them.

Today nearly half a million buffalo range across the face of North America, about half in the U.S. and half in Canada. It’s an incredible comeback for a species that hovered at the edge of extinction about a century ago.

Many of the 40,000 buffalo living in South Dakota today—still the state with the most buffalo, by many thousands—are direct descendants of those few calves the Duprees rescued on their reservation very near to this spot. For more than 40 years those buffalo were nourished and multiplied by the two families, the Pete Duprees and Scotty Phillips.

SITE 5. What happened to the Southern Herd?

While viewing these vast plains to the south is a good time to contemplate what happened to the southern herd that was decimated during the 1870s—several years before the buffalo returned here to Dakota Territory.

In 1871 an estimated 3.5 million head of buffalo grazed the southern ranges. Four years later all were gone, victims of white hide hunters with big guns. Only a few escaped to hide out in distant canyons. SD Tourism.

Visualize those wide-open plains farther south—200 miles and more distant—to central Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas and eastern Colorado and New Mexico.

In 1871 an estimated 3.5 million head of buffalo grazed those southern buffalo ranges. Only four years later—by fall of 1875—the entire southern herd was gone.

Most fell to commercial white hide hunters with long-range buffalo guns. It was made possible by the railroads crisscrossing those ranges, bringing huge numbers of eager hunters to previously inaccessible areas.

The first transcontinental railway Union Pacific crossed the nation in 1869, permanently dividing the buffalo into two great herds—the northern and the southern herd. Soon they became separated by 100 miles on either side as sporting men and hide hunters rode the rails and branched out from small towns along the way to a deadly slaughter of all buffalo within that range.

In the next few years other railroads cut across the heart of the southern plains. Farther north, this process delayed until after the Northern Pacific Railroad was able to cross the Missouri River at Bismarck in 1882.

The southern herd contained more buffalo, it was said, but on less territory than the northern herd, so they were somewhat more concentrated.

The “still hunt” or “stand” developed there as the systematic way to kill more buffalo faster with newly-developed big guns, even for inexperienced hunters.

The secrets of making a stand were simple: Lie on a ridge above a herd of 50 or so buffalo, brace the rifle on a rock and fire away. Shoot the leaders if they started to run, and the others likely hung around sniffing at them, waiting for another leader until all lay dead.

Thousands joined the rush. Hide hunters took along a skinner or two, a wagon and set out independently. Or they worked for merchants in small towns who outfitted their own wagons.

Railroads also hired buffalo hunters to furnish meat for their workers laying track. One of these was William (Buffalo Bill) Cody, who killed 4,280 buffalo in 18 months for the Kansas Pacific Railway. Later the famous Buffalo Bill took his Wild West show on the road and across Europe.

Other hunters claimed kills of 2,500 to 3,000 during a single season—November to February. One reported he killed 91 buffalo in one stand and another, that he shot 112 head within a radius of 200 yards in less than three-quarters of an hour.

Much of the meat lay wasted, and often even the hides rotted due to the inexperience and carelessness of hunters. At the height of waste, in 1871, every hide sent to market represented no less than five dead buffalo, according to William Hornaday’s careful estimates, gathered through extensive interviews and correspondence with military men, fur traders, hunters, railroaders and frontiersmen.

All too soon it was over. Last to go were a few scattered survivors that fled farther southwest to “wild, desolate and inhospitable” country inhabited only by desperate Indian bands. (For more details see Ch 10, Saving the buffalo, page 166, from the companion book “Buffalo Heartbeats Across the Plains,”)

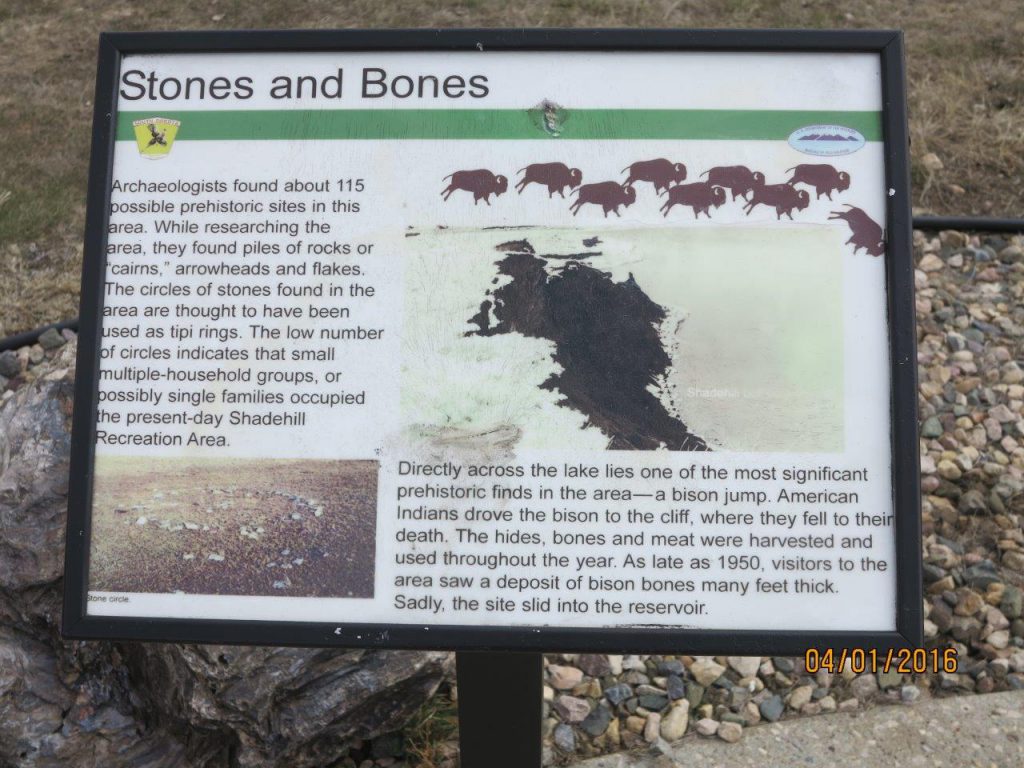

Site 6. Shadehill Buffalo Jump

Shadehill Buffalo Jump as viewed from the north side of the lake, damned in the 1950s. Photo by Vince Gunn.

For thousands of years before they had horses and guns, Native Americans in the northern plains had discovered the secrets of the buffalo jump. Research shows that a buffalo jump near Lethbridge, Canada, just north of the border, was used for over 5,600 years.

The rugged, broken terrain of the Great Plains was well suited to buffalo jumps. Grassy plateaus above steep, rocky cliffs often border rivers and creeks—as seen here above the waters of the Grand River.

This South Dakota Game, Fish and Parks sign describes the buffalo jump as well as 115 prehistoric sites and artifacts found in the area by archaeologists. However, the bones, once in two layers, one 12 feet thick and the other 4 feet on the side of the cliff, are gone, bulldozed off before the dam was built in the early 1940s and shipped to the west coast to make explosives in World War II. V Gunn.

Herds of buffalo frequently grazed on these plateaus above the cliffs. All it took was a stampede to drive them over the edge. And when panicked, wild buffalo stampeded easily, running faster and faster without regard to danger, the leaders unable to turn back.

The steeper cliffs you see ahead—when you look across the nearby bay to the left—was called a buffalo jump or mass buffalo burial by early homesteaders because of the bones exposed on its face. Large cedar trees fill the near draws, and on the other side of the trees are steep drop-off bluffs. A slump at this end shows where the bluff has fallen or was bulldozed off the top.

At this point the river holds the combined waters of both the North and South Grand and is now flooded by Shadehill Reservoir, dammed during the 1950s. To your far right is the earthen dam that holds back these waters.

Before the dam, the Grand River swung hard against the cliffs in flood stage, pulling down sections of the bank and its exposed buffalo bones—and revealing a fresh set of bones.

Archer Gilfillan, author of the classic book Sheep, described this bluff in 1939:

: Buffalo jumps have three parts, a steep cliff with a pile of bones below and evidence of drive lines above. Here a flock of wild turkeys visit a memorial to Mountain Man Hugh Glass who was mauled by a grizzly near the Shadehill Buffalo Jump site in 1823. V.Gunn.

“South of Lemmon, SD, 13 miles to Shadehill and then three miles west on a scenic road along the Grand River, is what has become known as the mass buffalo burial. This is a mass of buffalo bones exposed in a steep bank on the south side of the river. The river bank at this point is about 150 feet high.

“The bones are in two layers. The first layer, 12 feet thick, is about 25 feet below the top of the bank. Beneath this 12-foot layer of bones is a four-foot layer of earth. Then comes a second four-foot layer of bones, the bottom of which is still 100 feet above the bed of the river.

“The two layers of bones are exposed for approximately 100 feet up and down the river. Many of the bones are well preserved, although not fossilized. Horns and teeth are intact and there are large masses of almost indestructible stomach contents. All but the top layer of animals are crushed and smothered by those above.

“Two estimates were made by old timers of the number of buffalo involved, ranging from 500 to 20,000. . . . Obviously any estimate can only be guesswork at present, because no one yet knows how far the mass of bones extends into the hill.”

The two bone layers were well known locally and clearly visible on the face of the bluffs. Dorothy Durick Kroft of White Butte told of going there on a grade school trip during the 1920s to see the bones. Neighbors used the buffalo skulls to decorate their flower beds.

Settlers in the area reported the site and hoped it would be investigated by archaeologists. Finally it was, but too late.

During World War II there was great demand for bones in making explosives. People on the home front did what they could to help with the war effort. This is what happened to the Shadehill buffalo bone site, according to a neighbor, John//Don (dad) Merriman, who still lives south of the dam.

In the early 1940s, Merriman says, the land owner bulldozed off the top of the hill, uncovering the top layer of bones. He then scraped out that layer and the next, loaded and shipped them to munitions factories on the West Coast.

This was called mining bones. A Canadian source says, “Many buffalo jump sites were vigorously mined beginning around the turn of the century . . . to the end of WWII. Much of the natural phosphorus extracted from the bones went for the manufacture of munitions.” Earlier, bones also were used in fertilizer.

Renee Boen, Area Archaeologist for the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s Rapid City field office, reports that experts surveyed the Shadehill buffalo bone site in 1946 and again in 1992. They found no bones, but only the slump of earth at the bottom of the cliff.

After the dam, Shadehill Lake rose and covered the base of the bluff and heaps of earth. The only bones remaining lie deep under water, likely disintegrated over the years.

So, unfortunately, without evidence of butchering it can’t be proved whether this was an actual jump site or not.

Nevertheless, it illustrates the typical buffalo jump. The ideal site was a cliff that abruptly dropped off to a rocky bottom from a grassy plateau where buffalo commonly gathered to feed.

If the drop-off was hid by a slight rise so stampeding buffalo did not realize where they were heading, all the better, we are told.

When Indian scouts found a sizeable herd of buffalo grazing on a flat above a cliff—and the wind was right—the band made plans to stampede them. for a drive.

No one knew their prey better than did these seasoned hunters of the plains. They sensed the best way to direct each hunt—how to entice curious buffalo closer to the edge, when to drive hard and where to hide in safety as they plunged over.

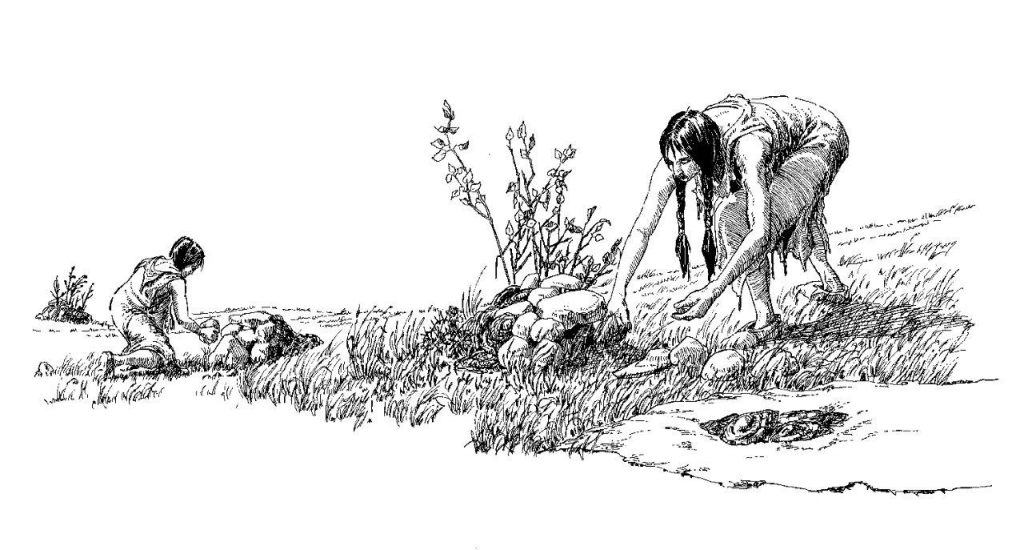

In this sketch ancient people set up tree branches with brush, rocks and clumps of sod to wave in the breeze, conveying a sense of motion as if people were waving hides along the drive lines. Courtesy of Imagining Head-Smashed-in book by Jack Brink.

Religious rites, traditional dancing and prayers played an important part in the hunts. These were people without horses or guns. They prayed for courage, skill and teamwork as well as cooperation from the buffalo.

When ready, the drive lines may have looked like this, directing the buffalo toward the low area and funneling them toward the drop-off. Drive lines sometimes stretched for miles above the jump. Courtesy of Shayne Tolman, Imagining Head-Smashed-in.

Women, children and dogs hid behind rock and brush piles at intervals on both sides of a wide drive line funneling toward the cliff, ready to leap out waving blankets at the right moment. Hunters unobtrusively formed a semicircle behind the herd.

Often the buffalo could be teased to the very edge of the cliff by young boys or a shaman. Dressed fancifully, perhaps in buffalo or wolf skins, the decoys attracted their attention and excited curiosity by prancing and bowing, alternately appearing and disappearing.

The closest buffalo began to watch and to approach. Then they eventually took chase, speeding toward the brink.

George Bird Grinnell wrote that the medicine man who brought the buffalo to the drop-off zigzagged this way and that, always attempting to lead, never to drive.

“The driving began only after the herd had passed the outer rock piles, and the people had begun to rise up and frighten them,” he said.

Panicked, the buffalo stampeded toward the precipice in a great mad run, charging blindly after their leaders, gaining speed, faster and faster. With the mass of huge animals ramming against them, the leaders lost the power to stop. Too late they saw the danger—and plunged over the cliff, landing in a fatal pile-up on the rocks below.

Scrambling down the cliff, hunters with sharp spears, stone knives and clubs finished off any crippled animals below and began the work of skinning and butchering.

At least a hundred buffalo jumps are identified in the northern plains. Likely thousands more are not researched or were mined of their bones before being studied.

Some are still accidentally being discovered in road-building—as was the Vore Jump when Interstate I-90 built through northeastern Wyoming and unearthed a sinkhole filled with buffalo bones (I-90 obligingly jogged south at that point). Or in excavations, as was another in that area while digging a water hole for cattle.

Other methods of harvesting large numbers of buffalo before Native Americans gained the help of horses included the surround (confusing the buffalo into milling in a circle), the impoundment (fashioning a pen at the bottom of a slope), and pursuing buffalo with dogs or on skis in deep ravines during times of heavy snow.

Before they had horses, hunters often disguised themselves to get close enough for a fatal shot with bow and arrows. The skins of wolves cause little fear among buffalo. Painting by George Catlin.

Then in the mid-1700s came horses and guns, and the glorious days of running buffalo with fast horses in the manner described here during the final great buffalo hunts of the 1880s began. (For more details see Ch 8, Way of the Hunt, page 128, from the companion book “Buffalo Heartbeats Across the Plains.”)

Side Trip A. Hugh Glass monument and Grand River Scenic Route

Many people like to stop at the nearby Grand River monument that marks the site near which Hugh Glass was left for dead after being attacked by a grizzly bear.

Hugh Glass was a hardy mountain man travelling up the Grand River with the Ashley and Henry fur trapping expedition party of trappers in 1823. You may have seen him in the Academy Award Winning the movie “The Revalent,”

While coming up the Missouri River on a keelboat, they had stopped at the Arikara villages at the mouth of the Grand River and traded for horses to travel overland.

The “Arikara” or “Arikarees,” known as Rees, seemed friendly but during the night they attacked the trappers, killing 13 men and wounding 10 or 11 more.

In retaliation the Army attacked and burned two large Ree villages.

Continuing up the Grand River, the trapping expedition was attacked again by Rees and two trappers killed. Shortly after, scouting near the forks of the North and South Grand in a heavily wooded area by the river, Hugh Glass was jumped by a grizzly bear.

The grizzly clawed and tore his body so badly that he lost consciousness and hovered near death. Major Henry left two men to guard him until his death and went on.

But Glass did not die. He lay unconscious with his terrible wounds as the days passed—with the two trapper guards growing increasingly anxious to get out of Ree territory. Finally, sure that he would die, they took his gun and knife and hurried off to join their party.

For five days he lay there. Finally he revived and in a nearly unbelievable feat of endurance, his leg badly maimed, he began to crawl back the way he had come. Wary of the vengeful Rees, he travelled only at night. Starving, he chased wolves away from a carcass, and caught small animals and birds to eat.

Finally he reached Fort Kiowa, near Chamberlain, 200 miles away.

There he joined a party of trappers going up the Missouri River, eager to return to trapping. For 10 years Glass continued to hunt and trap on the upper Missouri and then was killed by his old enemies the Rees as he crossed the ice on the Yellowstone River.

Legend has it that Hugh Glass swore revenge against the two trappers who deserted him, but forgave them when he met them again.

Below the monument and off to the right is the Shadehill Buffalo Jump.

“The steep bank just below this hill was the site of a large buffalo jump,” states the Forest Service map, “The Grand River and Cedar River National Grasslands: Land of vast horizons, rich history and enduring traditions.”

Also, on a high slope nearby, are the large faint letters “US-7th ”. Still visible, especially when the early spring grasses come.

They were carved by an Army detachment in 1891 on their way to protect settlers during a homesteader scare of an uprising over the death of Sitting Bull—which didn’t happen.

Site 7. Buffalo Lore on the Blacktail Trail

Native Americans honor the buffalo as sacred in song, dance, stories, artwork and ceremonies. In traditional plains belief, buffalo gave themselves up willingly as food for the Native people and furnished many other gifts as well—shelter, clothing, medicine and tools.

The Blacktail Trail—a 7-mile trail for walking, riding horseback or non-motorized vehicles—provides a nice place to consider the complex relationship between the buffalo and the Native people who lived and hunted here. CM Russell painting, ACM.

Blacktail Trail is a 7-mile loop for non-motorized use, constructed in 2004 by the Forest Service. Posts branded with deer antlers mark the trail. Interpretive signs give information on such topics as waterfowl, plants, wildflowers and the transition of this land from buffalo to cattle grazing.

A picnic spot and small fishing pond for youth offers a shady respite along the Blacktail Trail. FM Berg.

Spring-loaded gate keeps cattle out of picnic area. FMBerg.

A walk on the Blacktail Trail on a nice day offers a pleasant interval to consider the complex relationship between the buffalo and the Native peoples who lived here.

From being a source of food to providing social and cultural inspiration and close connections to spiritual life, the buffalo traditionally figured into all aspects of Native lives and they lived together in harmony.

Daily they thanked the buffalo and prayed for them to continue protecting them and helping them survive. Their close relationship with the buffalo is expressed by John Fire Lame Deer, “his flesh and blood being absorbed by us until it became our own flesh and blood. . . It was hard to say where the animals ended and the human began.”

Walking the Blacktail Trail you may see a sizeable cave or hole in the gumbo buttes.

Perhaps an aged Native grandmother told a creation story about this hole in the gumbo butte to children gathered around. Photo courtesy of Nicole Haase.

As you consider the lore and culture of the buffalo, we invite you to explore further. Many traditional stories speak to the mystery of the origin of life.

A common belief held by many plains tribes is of the creation of humans and buffalo and other wildlife emerging from a cave or hole in the ground. Perhaps it has been told of this very cave by a medicine man—or maybe an ancient grandmother told it to a circle of small children gathered around her.

How the World Began

This is the way the world began. Long ago this land was quiet and still. No people or animals lived on these hills. Not even in the green valleys or along the creek beds. No snakes, no lizards; no eagles or hawks soared overhead. All living things waited far underground. They waited for the right time to come out.

Great herds of buffalo lay there, all people, antelope, wolves, deer, rabbits, and even the little bird that sang ‘tear-tear.’ They waited as if asleep.

Then one day Buffalo Woman opened her eyes. She stretched and began to walk slowly among the others touching them lightly. As she did they began to stir and stretch. She saw an opening with a great shining light and felt warmth streaming into the cave from the light.

She walked toward the ray of sunshine. A young cow stood up and followed her. Then came another buffalo and another and soon a great line of buffalo was going out of the opening into the bright, warm, grassy place that was the earth.

Next the people awoke and streamed out one by one, the men, the mothers carrying their babies and holding little children by the hand. Then came all the other animals and even the small tear-tear bird stretching its wings and flying toward the warming sun.

They spread out in all four directions toward the horizon that circled all around. And the people saw that they were in a beautiful place—the right place—where they would live together with their relatives, the buffalo, and all would have plenty to eat.

Many different Plains tribes camped in these remote valleys to hunt buffalo and stayed to dry the meat and hides. Painting by CM Russell, ACM.

A traditional Cheyenne belief brought knowledge of how the sacred buffalo arrived on the plains.

In the old days, before people knew of the buffalo, a band of Native people camped near a spring at the head of a small rushing creek. Farther downstream the creek disappeared into a big hole in the ground.

The people were hungry and could find no food, not even a rabbit.

One day the leader said they must explore the hole and maybe they’d find something nourishing to eat. But who would go?

Three brave hunters offered to explore the hole. They knew it was dangerous—they might never return—but joined hands and jumped down into the deep darkness of the opening. When their eyes adjusted to the darkness they found a door and knocked.

An old Indian grandmother opened the door.

“Who are you and what do you want,” she asked.

They told her about the hunger of their people who were camped by the hole above and could find no food.

“Look out there.”

She pointed out her window and to their surprise they saw great herds of buffalo grazing contentedly.

Then she seated the hunters and gave them three stone bowls of buffalo stew. They ate their fill of the delicious food, and still more meat remained in the bowls.

“Take these special (magical) bowls of buffalo meat back to your people,” the grandmother said.

“Tell them I will send buffalo soon.”

They thanked her for her kindness and helped each other climb back up the hole without spilling any of the buffalo meat from her bowls.

The people were delighted to see them safe and bringing food. Everyone in the camp ate hungrily. But still more meat filled the three bowls.

The next morning they looked out of their tepees and saw vast herds of buffalo surrounding their village and covering the hills and prairies far into the distance. They knew this would be a good supply of food, shelter and clothing for their people.

Gratefully they gave thanks to the spirit grandmother and the buffalo for their generosity.

The 7-mile walking trail circles around a high butte overlooking broken, rugged country and topped by native juniper trees. FM Berg.

Petroglyphs on the Hills

Special places in these hills are revered. Rock carvings and petroglyphs can be found on cliffs and higher buttes throughout the west. Traditionally this art holds mystical power.

Petroglyphs on the rocky crown of a hill somewhat farther north [only a few dozen miles], in North Dakota, feature the carved tracks of buffalo travelling across a high point, capturing the view of a wide area.

The little-known site, not far from where the last buffalo were hunted on Standing Rock, is still visited with ceremony and offerings by Native people familiar with it. Note: Since these petroglyphs constitute a sensitive site, visitors who wish to visit them are requested to contact the ND Historical Society or archaeologists of the Forest Service.

The Black Hills are perhaps most revered of all, with their crown jewel, Bear Butte—a volcanic eruption at the north gateway to the Hills. Bear Butte rises from the flat plain in the shape of a large slumbering bear. With its sweat baths and private trails, it’s a sacred place for plains tribes, the site of many pilgrimages.

For many Lakota the cave of creation is in the Black Hills. The pine-covered hills there are coursed throughout with large caves, some among the largest in the world, most of them interconnected through tight honeycombed passages.

Because of her rarity and easy visibility at the home of the National Buffalo Museum and the World’s Largest Buffalo, we have added this stop to our tour. If you are travelling east on I-94, we hope you will stop and see this miracle for yourselves—a heritage that may stem from the famous Big Medicine himself.

In all of these places Native Americans have come to pray, to perform traditional ceremonials and offer gifts of tobacco, dream catchers, feathers and medicine bags. (For more details and Buffalo traditions see Ch 7, Buffalo lore, page 112 in the tour companion book “Buffalo Heartbeats across the Plains,”) In these pastures and in others here, ancient spirits walk.

Site 8. Buffalo Traits & Behavior

Older bulls often go off by themselves and may look lethargic. But don’t be fooled—buffalo bulls can turn on a dime, gallop 40 miles an hour and jump 6 feet over or into a fence, smashing it down. V Gunn.

There’s nothing quite like seeing live buffalo up close and personal—with sensible regard for safe distances of course.

While you journey throughout this region, you may notice private herds of buffalo belonging to area ranchers. A number of buffalo ranches operate within our tour area, but because they are not currently set up for entertaining tourists and for the safety of all concerned, as well as privacy and insurance issues, they remain anonymous at this time. However, you are welcome to stop along public roads to view them—quietly and with respect, please.

You may also see buffalo at closer ranges in Jamestown, N. D., or driving among them within their pastures in Theodore Roosevelt National Park, near Medora, N.D. (check the prairie dog towns toward evening) and in Custer State Park in the Black Hills.

Buffalo are large, strong, unpredictable, and potentially dangerous. Admire them from afar, but DO NOT APPROACH. Above all, DO NOT enter pastures with buffalo or drive through gates without permission.

Observe buffalo behavior

In most seasons the cows and bulls sort themselves out into separate male and female groups. Young bulls hang around with their mothers until two or three years old, when they join other males in small bachelor herds.

The Johnson herd visits a reservoir near Hettinger on its morning travels. FM Berg.

Buffalo cows are generally affectionate and attentive, fiercely protective of their calves. They are known for ease of calving, with relatively small newborns weighing only 30 to 50 pounds. When born, buffalo calves are red-gold with a thick growth of long woolly hair, which soon darkens, especially on the crown of their heads.

They are born without a hump—but that doesn’t take long either. By three months the hump emerges and so do inch-long stubs of horns. Calves shed their baby coat after three or four months, to be replaced by a growth of fine, new, dark hair. As yearlings, their horns grow into straight, conical spikes, four to six inches long, and perfectly black.

Calves can be playful. In his book The Time of the Buffalo Tom McHugh describes a group of seven exuberant calves.

Calves can be playful, but mothers are watchful and protective. The Oneida herd in Wisconsin. Photo courtesy of Oneida Tribe.

“All of a sudden they perked up their tails, kicked their hind legs in the air and bolted across the meadow to engage in what looked like a game of tag. As they milled chaotically, one calf bounded out of the little band, inviting another to follow.

A companion came forth and the leader broke into a rapid gallop, challenging him to a race around the herd. Before long all seven were tearing about in a frenzy of activity, butting, kicking and bounding to and fro in carefree frolic.”

During this play the calves uttered “sounds as unique as they are difficult to describe.”

Buffalo bulls often display a strong sense of responsibility for protecting the herd, even today. When they feel threatened they often come together in a tight group with bulls on the outside, cows and calves inside.

Dominance issues

Buffalo are social animals with a great understanding of where they stand in the herd’s ranking—or pecking— order. Size makes a difference in ranking, but other traits matter as well, including strength, fighting skill, endurance, maturity and aggressiveness.

McHugh spent three months studying the hierarchy ranking through patterns of dominance and submission in a Jackson Hole Wildlife Park herd of 16 buffalo. He named each individual and recorded its rank through interactions with each of the others. Most of their interactions were peaceable, as all knew and understood their rank order compared to each of the others.

Often a dominant buffalo walked over and displaced subordinates at a pile of hay just by his presence, without force or threat. The low-ranking animals simply moved away while wending their way carefully through the herd to avoid other superiors, indicating submissiveness. McHugh noted all this was subtle and almost imperceptible, but universally recognized and respected by each animal.

About one-fourth of the interactions involved warnings and threats or actual use of force. This might involve a steady stare, swinging horns menacingly, or placing a chin on the rump of a subordinate to force it to move away.

The Standing Rock Tribal Herd grazes through a prairie dog town in the Porcupine Breaks or buttes. Photo courtesy of LaDonna Allard.

When threats failed, a battle might follow. McHugh says disruptions occur when new individuals enter the herd, calves are born, or young bulls begin to assert their increasing size and strength over formerly superior cows. Once hierarchy is reestablished, combat dies down as each individual recognizes and accepts its place in the herd.

During breeding season—also called the rut—fights are staged between big bulls as they move between herds and fight for dominance. In the wild this was the time when males and females came together in huge herds.

A challenging bull might grunt, snort, blow or growl to get a female’s attention and the defending bull roars back. The challenge of a bull buffalo is described as an impressive bellow or growl that closely resembles the roar of a lion.

Cows normally breed in August or September and calve from mid-April through June, with a gestation period of about nine months or slightly longer.

Under favorable ranching conditions today buffalo cows live to 20 or 25 years old, producing a calf each year. In the wild, such as in Yellowstone Park, they rarely live past age 15 and may calve only every other year.

Working them in the chute can be stressful for bison. Being in the chute alone is stressful, but so is being too closely crowded with several others. It’s important for handlers to work quickly and quietly. FM Berg.

Rare visit by students allowed in working pens. Oneida photo.

Buffalo coats and shedding

You may be surprised to see that by early summer a buffalo’s rich brown winter coat is faded to light brown, with patches of it flying in the breeze.

William Hornaday described this shedding process in his 1889 Smithsonian study. “Promptly with the coming of spring, if not even the last week of February, the buffalo begins the shedding of his winter coat.

“It is a long and difficult task, and with commendable energy he sets about it at the earliest possible moment. It lasts him more than half the year, and is attended with many discomforts.”

The new hair grows so rapidly and densely “that it forces itself into the old, becomes hopelessly entangled with it, and in time actually lifts the old hair clear of the skin. The old and the new hair cling together with provoking tenacity long after the old coat should fall, and on several of the bulls we killed in October there were patches of it still sticking tightly to the shoulders.”

The bull attacks clay banks. He rubs on trees. He fights. He wallows. “When he emerges from his wallow, plastered with mud from head to tail, his degradation is complete,” wrote Hornaday. “He is then simply not fit to be seen, even by his best friends.”

Bulls wallow to shed winter hair, to get rid of insects and to establish dominance. Here young bulls take their turn at a wallow. SD Tourism.

The bull’s one redeeming feature in all this rag-tag display is “the handsome black head, which is black with new hair as early as the first of May, preserving the bull’s majestic appearance throughout this long shedding effort.” And by fall a wondrous transformation takes place and the rich brown coat is luxuriant and fully grown.

“The buffalo stands forth clothed in a complete new suit of hair—fine, clean, sleek and bright in color, not a speck of dirt or a lock awry anywhere.”

New growth hair on the beard and front can reach amazing lengths. From his own hunt for Smithsonian museum specimens Hornaday reported: “I have a tuft of hair . . . which measures 22½ inches in length, from the frontlet of a rather small bull bison. The beard was correspondingly long, and the entire pelage was of wonderful length and density.”

Be aware that buffalo are wild animals—as are lions and tigers born in zoos. They are not domesticated, even in the sense of undergoing a selection process to increase traits considered desirable and breed out undesirable traits, which passes down to offspring. Thus they are unpredictable.

In a seminar for tribal buffalo managers, Dr Trudy Ecoffey, InterTribal Buffalo Council Wildlife Biologist, cautioned the managers about getting up close. Her advice was “Don’t!”

“It is difficult for people who are around buffalo often to tell when an attack will occur, and for the person who is never around them almost impossible.”

The lumbering walk of the buffalo is deceiving, she said. They can turn, accelerate and charge in a heartbeat. A clue to their agitation is the stubby tail. When it hangs down and switches naturally, the buffalo is usually calm.

But if the tail flips up and over the back he may be ready to charge. Other signs of anxiety are grunting or shaking the head. These actions should prompt people to give the buffalo plenty of room and preferably, to place something huge between them and the buffalo, warned Ecoffey.

If you are not seeing any live buffalo, note that an indication of a buffalo pasture is usually higher fences. In the distance buffalo show up as wedge-shaped—with large extended forequarters and small, slender rear ends—compared to the blocky, rectangle-shapes of cattle and rounded curves of horses at a distance.

Buffalo prehistory

The first buffalo are believed to have arrived in North America about 43,000 years ago, crossing back and forth from Asia on the Bering Land Bridge in Alaska, along with mammoths, mastodons, the wooly rhinoceros, horses and camels. However, recent evidence suggests an earlier wave of bison may have come 195,000 to 135,000 years ago and then died out, as reported in 2017 by the University of Alberta, Canada.

One giant bison species stood one-fifth larger than our modern buffalo with horns 10 feet across. Most of these large mammals—including all buffalo species except one—vanished around 9,000 years ago, a mass extinction that is still a mystery. Horses found a new home in Asia before dying out here, and returned later with Columbus and the Spanish Conquistadors.

Modern American buffalo developed into two subspecies—the prolific plains buffalo of the open country and the wood buffalo of the forests and far north. Thus under scientific classification, the American plains buffalo is listed as genus Bison, species bison, and subspecies bison—for Bison bison bison. The wood buffalo is Bison bison athabascae.

Although controversial for a time whether they were separate species, recent research at the University of Alberta conclusively shows genetic differences. Plains buffalo have a more rounded hump, with its highest point directly over the front legs, and more predominant hair character—large chaps, a full beard and neck mane and a clearly-defined cape.

In contrast, the larger wood buffalo tend to have higher, often sharply-angled humps located farther forward on the body. They wear no chaps, sport only a thin pointy beard and skimpy neck mane and their less-defined cape blends smoothly back to the loins. Wood buffalo are usually a darker color.

Conserving the buffalo: Public, tribal and private herds

How many buffalo were here when the first Europeans arrived? In the 19th century, naturalists estimated 60 million or more, based on an assumed range of 3 million square miles.

However, range experts now put that number at closer to 30 million, given we now know their usual range was smaller, about 1.2 million square miles.

Today, buffalo in the United States and Canada total nearly 500,000, about half of them below the international border and half above. As the railroads, highways, and cities grew in the Great Plains, the massive herds dwindled to an endangered level, prompting many to look at ways to save the buffalo.

Today’s buffalo live in free-range herds within national parks, special herds through Indian tribes, and in private herds. A few live in zoos and other wildlife parks. These hardy animals live and thrive in all 50 states, every Canadian province and many countries throughout the world.

Buffalo vs Bison? What shall we call them?

What shall we call this magnificent Monarch of the Plains—buffalo or bison?

Call them what you are comfortable with, what you like best—and don’t feel guilty if that’s “buffalo.” It’s mistaken to believe they “should” be called “bison.”

Professor Lott, who surely loved and understood the animal as much if not more than any other scientist who wrote of them, used both terms, almost interchangeably.

“My scientist side is drawn to bison . . . scientifically correct and precise,” he wrote. “Yet the side of me that grew up American is drawn to buffalo—the name by which most Americans have long known it. Buffalo honors its long, intense and dramatic relationship with the peoples of North America.”

As the grandson of the chief ranger, Lott was born on Montana’s National Bison Range and grew up there and on a ranch within sight of those buffalo. Later he specialized in Biology and wrote the book American Bison as a college professor.

Indian tribes often use names in their own languages, such as the Lakota Tatanka and Pte.

Hornaday, who comes in a close second in his passion for buffalo as a scientist—initially intrigued with them as a taxidermist for the Smithsonian and going on to devote most of the rest of his life to the species—calls them bison in his own writings, but he also wrote in 1889:

“The fact that more than 60 million people in this country unite in calling him a buffalo, and know him by no other name, renders it quite unnecessary to apologize for following a harmless custom which has now become so universal that all the naturalists in the world could not change it if they would.”

So don’t apologize if buffalo comes most naturally for you. Of course in scientific usage it is bison—as is bovine, equine and canine. But we don’t call the cow, horse or dog those names in normal conversation do we?

Buffalo actually comes from French fur traders who called the animals les boeufs (la buff), for “the beefs” meaning oxen or bullocks. It has a long history in North America dating from 1625 when first recorded—even before bison was used, in 1774.

It even has a verb form—to buffalo (meaning to bewilder or overawe).

Here where buffalo are raised we quite naturally prefer the term buffalo. It’s a good, solid, friendly yet respectful label, with no formality separating us from these majestic animals. (For more details see Ch 6, Noble Fathers, page 92,and Ch 11, Buffalo Ranching Across America, page 186, from the companion book “Buffalo Heartbeats Across the Plains.”)

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog