The Vore Jump site is considered important because of its location and the period of time it was used for buffalo hunting.

Literally it is located a stone’s throw from a major highway—I-90—the longest transcontinental freeway and interstate highway in the US which crosses the US from Boston to Seattle (3,021 miles; 4,862 km).

This northernmost transcontinental route was established in 1956, so it sees lots of traffic, especially in summer with families traveling to mountain vacation lands.

In fact, it made a rare curve to avoid the Vore Buffalo Jump itself—which was discovered by highway engineers surveying the I-90 route.

Because it is on a major route, people on the Vore Foundation board point out that their Buffalo Jump is the most accessible of the major Plains Indian sites to the traveling public.

“Thus it provides a perfect physical context for illuminating Plains Indian culture and history and presenting it to visitors.”

The importance of the Vore Jump is that it marks a clear transition in major movements of Native Indian populations from east to farther west after European settlement began on the east coast.

It was used as a buffalo jump for about 250 to 300 years, beginning in around 1500 when Europeans were just beginning their encroachment of lands on the Atlantic Seaboard.

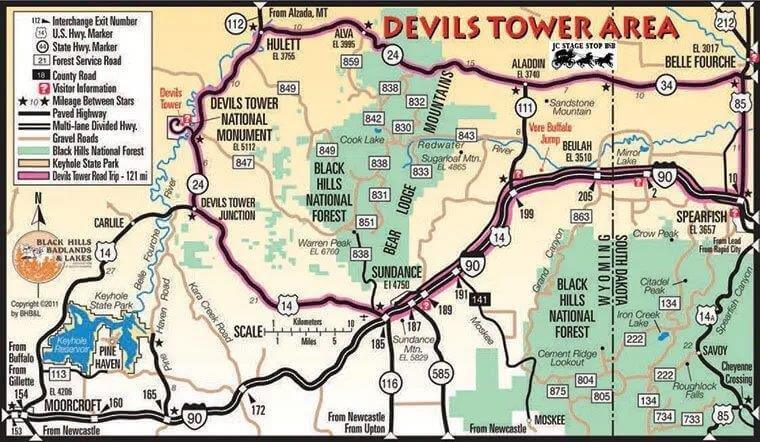

Map shows where I-90 goes west from Spearfish SD in the Black Hills, takes a swerve at the Vore Buffalo Jump site, from which it’s only a few miles to Devils Tower National Monument and on beyond to the east entrance of Yellowstone Park via Beartooth Pass and Cooke City. Photo credit Vore Buffalo Jump Foundation.

At that time, all Native weapons and implements were hand-made of bone or rock, sometimes traded from one tribe to the next. Dogs pulling travois were used to haul their goods.

Then came a time of western movement of Indian tribes. Many tribes left their homes and adopted a nomadic Plains lifestyle that followed buffalo herds, embracing a new culture interrelated with and dependent on the buffalo for most all their needs.

For most of their history, meat and hides obtained from buffalo jumps were used by Native Americans for their own subsistence. But as manufactured items became available, Plains tribes began trading for them with tanned buffalo robes, jerky and pemmican.

Gradually metal tools and guns became trade items that occasionally reached the Plains tribes, and they learned to value trade goods from various sources—beads, cloth, blankets, guns, knives and unfortunately, alcohol.

Then during the early 1700s some tribes, beginning with the Comanche and Apache in the south, began trading for horses that escaped the Spaniards—who had tried mightily to prevent Natives at Mexican border missions from learning to ride.

By 1750 horses reached the northern tribes, led by the Shoshone, who raised great herds of horses at an early date.

Native tribes understood the advantages of the horse immediately. They grew up from childhood with horses, trained them, rode long distances in war, raiding and hunting. They became some of the greatest horsemen the world has ever known.

And since on horseback, hunters could surround a herd of buffalo, ride alongside and kill their target with one bullet to a fatal spot—usefulness of the Vore Buffalo Jump came to an end about 1800. It had outlived its purpose.

Eventually horses made buffalo jumps obsolete, but trade expanded. Archaeology at the Vore Site will help us understand when and how this transition occurred.

We might say that the Vore Buffalo Jump Foundation is notable further because it is a non-profit organization in the finest sense. More about that later.

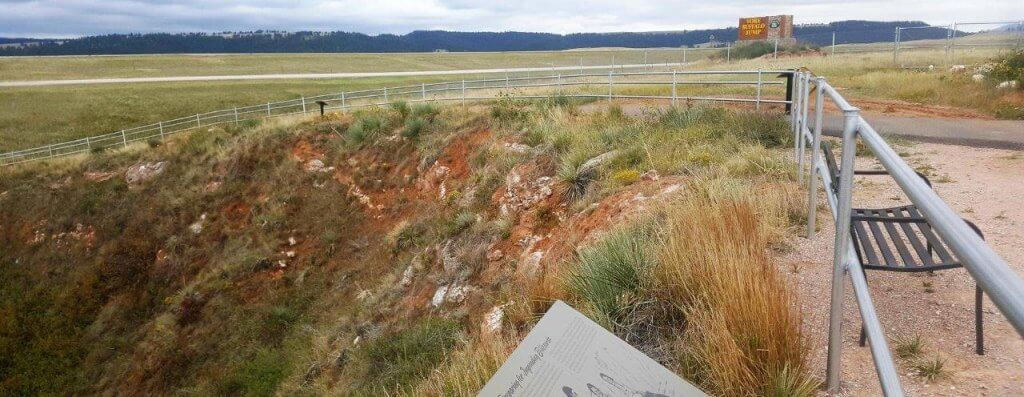

Interstate highway I-90 swung to the left in this photo to avoid the historic Buffalo Jump at the Sinkhole. It gets a great deal of east-west travel and is considered a major route to summer vacation lands in the mountains. VBJF.

When they were told they had to erect a handrail or close, the foundation had pretty much spent its last dime and requested donations. Local people who supported the project stepped up. Even a touring 4th grade class opened their pockets and donated—and the railing went up quickly. VBJF.

Who used the Sinkhole Jump?

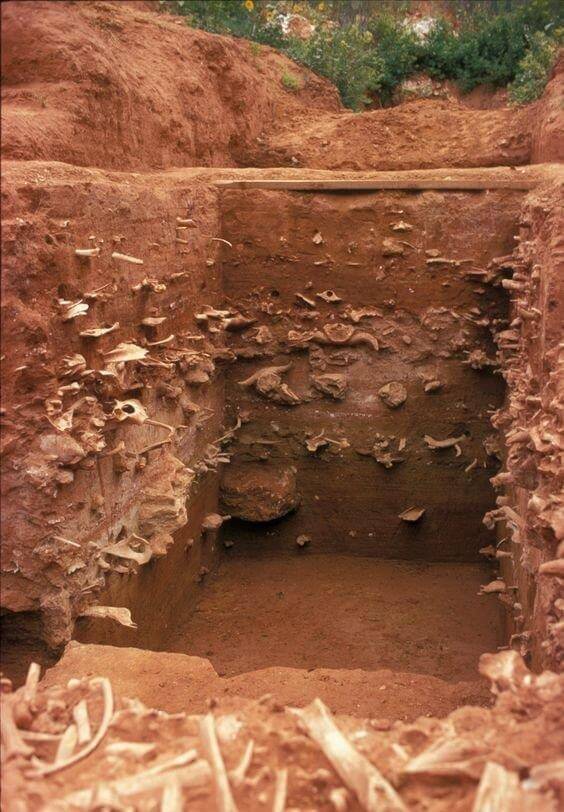

Buffalo bones are found at 22 levels at the Vore site, the top levels are most recent from about 1800. VBJF.

While no specific level of the sinkhole has been designated to one cultural group, the tribes who most likely used the Vore sink hole were the Lakota Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Crow, Kowa, Plains Apache and Shoshone, according to Greg Pierce, PhD, a Wyoming Archeologist who earned his graduate degree at the Vore Buffalo Jump site.

Dr Pierce’s specialty was weapons and implements used for butchering the bison trapped in the sinkhole at Vore. Pierce also served on the Vore Foundation Board for 12 years

Working with only the 6 upper bone levels, he found fewer stone tools and flakes used in the upper, most recent levels. This means a greater percentage of metal tools were being used more recently than before.

This was indeed a time of gradual transition from stone age tools to new reliance on metal.

For example each of the 5 top levels (with level 1 as the most recent, at about 1800) showed metal cut marks on the bones as well as stone marks. However the percentages clearly reveal the transition moving from stone to metal.

Near the top, in the most recent Levels, 1 to 5, he found between 100% and 63% of the bones showed gradually increasing numbers of metal cuts. While at Level 6 only 33% of butchering attempts were made by metal implements.

“An analysis for bone surface modifications can identify human made marks such as cutting, chopping and scraping associated with bison skinning, butchering and marrow processing. This analysis can show the difference between stone and metal tool marks,” he writes.

Even though researchers at Vore have as yet found no metal tools, Pierce was able to identify the various implements used from cuts on the bones. Some of the evidence required a microscope to see clearly.

“Since less than 10% of the Vore Site has been excavated, steel implements may yet be found,” he says.

Arrows can often be identified by the area they came from in trade.

All weapon points found at the Vore Site are arrow points like these. Except that all found here were broken or no longer re-workable. A broken arrow point or stone tool was found in nearly every square meter in every layer during excavations at Vore. VBJF.

“These tribes all occupied or moved through the area between approximately 1500 and 1800 AD,“ Pierce wrote in his research report ‘State Archaeologist reports on his Research at Vore Buffalo Jump.’

“Environmental changes during this time resulted in improved foraging for bison in the region, resulting in larger, more densely distributed herds.

“Taking advantage of the situation many native groups intensified their bison hunting activities. This brought a number of tribal groups living in the Great Lakes region of North America slowly moving westward onto the Plains as bison hunting took an ever increasing role in their subsistence practices.

As part of this transition these people gave up a semi-sedentary village lifestyle for a bison hunting way of life—on foot. By the 17th century Euromericans and Euromerican goods began to influence native lifeways. Native American groups began moving westward away from European settlements.

This influx of new populations had an impact on existing political alliances, hunting practices and tribal territorial claims. In some cases these movements led to conflict pushing existing populations in the region further west or south.

“This domino effect ultimately proved to be yet another factor in the migration of tribal groups into the High Plains and Black Hills during the 18th and 19th centuries.

“Part of this process involved the dissemination of the horse and gun throughout the West. The horse, gun and accompanying Euromerican goods reached the Black Hills and High Plains by at least the 18th century and were quickly integrated into native hunting and warfare practices.

“The most important result was the development of the Plains horse culture,” Pierce pointed out. “The horse brought the Native Americans a freedom of movement never possible before and many plains tribes developed a nomadic lifestyle that followed the herds.“

Stone tools transitioned to Metal in Recent bone Layers

Thus Pierce points out that the Vore site saw the transition from stone to metal tools, and it saw the transition from the bison jump method by men on foot to the introduction of the horse.

When discovered the Vore Buffalo Jump was merely a weed-covered hole in the ground. Arrow points and blades found in the Vore bone bed are mostly broken or unusable. It’s clear the good ones were not left behind, but were valued, pulled out and kept to use again. VBJF.

“The unique history of the use of the Vore site makes it an ideal dataset from which to examine this tumultuous era as this single site provides a cross section of time, in one location that researchers can use to investigate historic events, activities and processes,” he concludes

All weapon points found at the Vore Site are arrow points. An arrow point or stone tool was found in about every square meter in every layer during excavations here.

The arrow points found in the site were those lost during butchering or were broken and no longer re-workable

Many of the stone tools found in the sinkhole are Knife River flint from quarries in North Dakota about 200 miles to the northwest. These quarries were likely controlled by the Crow during the time of Vore Site use.

The crowd joined hands around the new tipi for a prayer and Friendship dance. VBJF.

Learning to Make a Tipi

A special event took place at the Vore Buffalo Jump site in 2014 when the Foundation Board decided they needed a tipi to exhibit in one of their buildings.

Not just any tipi, but an authentic tipi from the time the Vore Buffalo Jump was being used. They had high standards. That meant it had to be small enough and light enough to be hauled by one or two dogs.

People in charge of the Vore Buffalo Jump have tried to use ancient Native American methods and authentic Native tools in their work when possible.

The buffalo hides had to be tanned in just the way women tanned and sewed them together for tipis long before they had horses. So why not find Native women to do it?

They soon found that the main expert in the art was closer than they imagined. The ancient technique was taught at Chief Dull Knife College in Lame Deer, Montana—not so very far away.

A class of Northern Cheyenne women in Chief Dull Knife College was studying just that. They had their own mission and said they’d be delighted to come, tan buffalo hides the old way and make the proper kind of tipi needed right on the Vore site itself.

In fact it would be ‘a dream fulfilled.’ The seven women who came on that mission were Larie Clown, Victoria Haugen, Lori Killsontop, Tee Jay Littlewolf, Maria Russell, Rebekah Threefingers and Jodi Waters.

The last time their community had constructed a similar tipi was around 1877 when herds of buffalo were on the verge of extinction and reservations were being established.

The Vore foundation was determined to get grant funds together and do it right. And they did.

“The 5 buffalo hides, sinews and other materials needed were expensive,” says Jackie Wyatt of the VBJF, who lives in Sundance WY.

“To bring this long-sought dream into reality required the effort of the Cheyenne workers, Larry Belitz who directed the tipi-making, and behind-the-scene work of Vore Buffalo Jump Board of Directors.”

And so the tipi was constructed on site by students accompanied by an instructor from Chief Dull Knife College under the guidance of Larry Belitz, the world expert on the technique.

The tipi made by the Northern Cheyenne women found a home in the big research building down in the sinkhole. Because the Vore Jump was used before the time of horses, the tipi, made from 5 buffalo hides, was of the smaller size to be pulled by dog travois. It weighs about 90 pounds so the travois would probably be pulled by two dogs. VBJF.

When finished, the tipi found a home in the large research building in the sinkhole, providing inspiration to researchers and volunteers as they work to excavate new layers of bones and develop new educational panels.

Reaching out to the Next Generation

Kids enjoy the BJ Bison sketches and other age-specific materials designed for them as they learn about the ancient heritage of their state and region. VBJF.

Leaders in the Vore Jump Foundation feel a special responsibility to teach the next generation of young people about their heritage. They feel certain the legacy and future of this delightful site is in the hands of 4th graders and their teachers.

The location of the Vore sinkhole near the corner of four states—Montana, Wyoming and North and South Dakota, and literally only a stone’s throw from Interstate 90—makes it very convenient for schools in the area.

The BJ Bison drawing above is familiar to youth who’ve been on the Vore tour. A number of educational materials are directed specifically to their age group—especially the 4th graders who generally study their state’s history. After that, 8th graders and high school students who take Plains history are targeted.

The off-season field trip program hosts about 1,000 students every year. The Vore Site stays open from June 1 through Labor Day in September from 8 am to 6 pm.

After that it is available for schools and off-season tours by request. Volunteers happily give tours to school kids.

Contact for teaching staff please call 307-266-9530; Email: info@vorebuffalojump.org or write Vore Buffalo Jump Foundation, 369 Old U.S. 14, Sundance, WY 82729.

The Vore Buffalo Jump hosts about 1,000 students every year. It’s location near the corner of four states—Montana, Wyoming and North and South Dakota, and literally only a stone’s throw from Interstate 90—makes it very accessible to schools in the area. VBJF.

A true Non-profit: Vore Buffalo Jump

The non-profit Vore Buffalo Jump Foundation board operates like a true non-profit. They have virtually no administrative costs.

Think of what that means. That many highly qualified people are contributing their talents. It’s a labor of love.

And sure enough, Jackie Wyatt tells me that 8 people living within 50 miles serve on the Foundation Board—all volunteering their time, talents, concerns and money.

Another 10 or 12 persons serve as an advisory board. These include educators, college professors and US Forest Service anthropologists, who also volunteer their services.

These people rise to the occasion when needed. Contribute their time, talents and cash to this amazingly difficult million-dollar project that suddenly dropped in their laps, only because of where they happen to live.

And when I reflect, it’s to realize this is what rural people do all the time. They get the job done. These people won’t fail in their mission. It is indeed a labor of love.

The Vore decision makers also have high standards, not to be compromised.

For example when they commissioned the construction of the tipi. They found the best talent and paid what was needed.

For the Northern Cheyenne women too, the tipi project was a labor of love. They called their assignment ‘A dream fulfilled.’ To have the rare privilege of constructing a tipi in the old way, the way it ‘should’ be done—a task their community had last completed in 1887 apparently was reward enough.

At Vore only the hired interpretive staff are paid—admission charged visitors during summer pays their salaries. The buildings and exhibits have been funded through grants and donations. The VBJF took out a loan in 2013 to put up the tipi and drill a well, which allowed them to put in restrooms.

I’m impressed and overwhelmed by their generosity and willingness to go the second mile.

In this day and age we are all too familiar with so-called “non-profits,” launched by well-meaning people, perhaps at the start. But who go on to give themselves impressive titles, paying big salaries to themselves and relatives, making sure that donations pass through their own greedy hands, till there’s almost nothing left for the cause they claim to fight for.

The Vore Jump Foundation is a polar opposite of that. It’s well worth our consideration. Dedicated people like Jackie Wyatt and Gene Gade put in many hours but do not expect or want payment for their talents and work.

For instance, Gene Gade who writes well-researched articles in the VBJT newsletter took the job as County Extension Agent in Sundance Wyoming many years ago.

He must have thought to himself from his County Agent vantage position, “‘I know how to do this; I need to help,’ and put in over 20 years as president of the non-profit VBJ Foundation.

From his great USDA Extension conections he helped to develop and guide the research, education and economic potentials of the Vore site for all those years.

Now in retirement he and his wife moved to Oregon to help a daughter with their grandchildren.

From there he still writes timely articles for the Vore Buffalo Jump Newsletter, continuing to research fresh information.

In Oregon he’s involved in working for Native American causes from a new vantage point from which he says, “The devastation of the Columbia River salmon has been as disastrous to Indigenous people of the northwest as the near extinction of bison was to the Plains tribes.”

And how much is he paid for all this? Don’t be ridiculous.

And there’s Jackie Wyatt. When the Foundation Board was required to build a railing for the trail down to the research sinkhole or be closed down, she made many phone calls and people donated what was needed. Jackie says even a 4th grade class that happened to be there on a field trip emptied their pockets and gave what they could when they heard. Isn’t that cool!

No one is getting wealthy from donations to Vore Buffalo Jump. All funds go into essentials to keep the place running, add improvements and to advance ongoing research at the site. Concerned people just donate more. That’s what is done in rural communities—it is needed and they don’t count the costs.

The Future

The Vore Foundation is actively working to establish permanent facilities with the goal of creating a world-class research, education and cultural center at the Vore Site.

Foundation leaders are quick to point out that because less than 10% of the Vore Buffalo Jump has been excavated “there is potential for decades of scientific research in several different disciplines…archaeology, tribal ethnohistory, zoology, geology, and paleoclimatic studies.

“Dozens of technical papers based on data from the Vore site have already been published. Just as the Black Hills attracted Native Americans, visitors from around the world are fascinated by Plains Indians.”

The Foundation has resolved to save the past for future generations, and we know they will.

However our admission fees and generous donations will help as they continue their research and development of this major archaeological site of the Late-Prehistoric Plains Indians.

The Vore Buffalo Jump Foundation Research, Education, and Cultural Center project does need our help. Its a true non-profit foundation that counts on donations to meet the financial requirements of their vision for the Vore Buffalo Jump.

They also appreciate Volunteer assistance and ‘in-kind’ contributions.

If you believe in this cause your support is most welcome and certainly needed. (Must admit I support these people who nourish the Vore Jump at least partly because what they are doing is exactly what I’d love to have happen in our own area of historic buffalo sites. Maybe we could build a useful, carefully accurate and active Buffalo Visitors Center that comes off as wonderful and is fully supported by the home folk.)

In rural areas this is the way people mostly get things done—whether fighting fire, running life-saving ambulances or designing tourism projects. Volunteers do what’s needed.

And for sure, they’re the best kind. Many donations even come in anonymously! Who needs or wants credit for helping do something this good?

The Vore Site is managed by the 501(c3) non-profit Vore Buffalo Jump Foundation (VBJF) board. I can’t help telling them each one is a hero—”You are truly unsung heroes! You get the job done!”

Donations and your comments may be sent to:

Tel: (307) 266-9530

Email: info@vorebuffalojump.org

Vore Buffalo Jump Foundation

369 Old U.S. 14

Sundance, WY 82729

_______________________________________________

NEXT: The Shrinking Buffalo

_________________________________________________

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog