Louis Garcia and his wife Hilda Redfox of Tokio, ND, married for 48 years. Photo courtesy of author.

Louis Garcia, honorary tribal historian for the Spirit Lake Nation, teaches carpentry at the Cankdeska Community College at Fort Totten, ND. He is the author of “Grass Dance of the Spirit Lake Dakota,” published by Cankdeska Community College. It is available in the college bookstore and at www.writtenheritagebooks.com. He writes a column in the Benson Country Farmers Press entitled; A Message From Garcia: The History and Culture of the Spirit Lake Nation, and has written about 120 of these feature stories. Garcia is married to Hilda Redfox. A tribal member for 48 years, and 3rd generation Dakota Presbyterian Church Elder, she is employed by the Tribal health Department. They have a son Robert age 44 and a grandson Chandler and live near Tokio, ND on Spirit Lake Reservation.

For the Plains Indian nothing is more exciting and exhilarating than hunting buffalo or more enjoyable than feasting on their flesh.1

To the Plains Indian the buffalo was the source of life; this bovine scientifically called a Bison (Bison bison) provided everything required to exist in a plains environment. Every part of the buffalo was utilized including their excrement which was used for fuel.

The Dakota term for a buffalo hunt is Wanasapi which appears to be contraction of a descriptive name. During the period named Dog Days, before the coming of the horse, when dogs were used as burden carriers, the hunt was more individualized.

Hunters would don a wolf hide and crawl on all fours up to the herd. Buffalo have poor eyesight and depend on their sense of smell. As there were always wolves prowling nearby, the hunters would go unnoticed.2

Larger groups of hunters employed a Park, which was a fenced enclosure or by driving a herd over a precipice called a jump.

With the arrival of the horse circa 16853 and shortly thereafter by the white man, the herds of buffalo began to decline.

The beginning of this decline is attributed to disease4 by some writers (although this was disputed by Theodore Roosevelt5) and later overhunting. Buffalo herds were increasingly harder to find.

The threat from the Canadian Métis from the Winnipeg-Pembina area, who also hunted in large groups; and according to Indian territorial rights were trespassing on Dakota tribal lands.

These mixed race people increased the pressure brought upon the buffalo population.

One of the last of the large buffalo hunts occurred in 1882, the year known as “Wableza Lakota ob wanasapi waniyetu,” the year Major James McLaughlin went on a buffalo hunt with the Lakota and Nakota.6

Crazy Walking was the hunt leader and Running Antelope the camp crier.7 The location of this hunt was in Adams County, North Dakota along Flat Creek Cannahma Wakpala.8

The plains people were always on the move, when the herds moved they moved.

The Dakota /Lakota would have two large hunts a year, once in the spring and once in the fall. In the spring, the hunt was usually held in April.

Later on the people gathered for their annual tribal Sun Dance Ceremony in late June and then dispersed to gather other sources of food such as berries, nuts, and tubers. Deer, elk hunting, and also fishing supplemented their diet.

In late September they gathered again for the fall hunt. The Dakota / Lakota spring and fall hunts which were termed “running buffalo,” were an elaborate affair full of prayer, ceremony, and symbolism.

During the buffalo hunt and in time of war the large camp came under marshal law.

Louie Garcia in dance regalia. He began Native American dancing as an 11-year-old with the Boy Scouts. Photo courtesy of author.

A prominent family was selected to set up a tent in the Cokayata or center of the camp. It was a great honor for a family to give up their home. This tent became tribal headquarters called a Tiyotipi or Tent of Tents. No menstruating woman could go near this now consecrated council tent.

Each family had a designated camping location with in the circle of tents. If the camp was exceedingly large then the Tiyotipi was made larger by pitching two or three tents together called a Tiyokiheya.

Ten men were selected as leaders of the hunt or times of war named Wicaŝtayataŋpi— Honored men. They were chosen by unimus decision as they could have no blemish on their reputation.

They became the Wayacopi or judges. These ten men made sticks about six to eight inches long and a finger in thickness which they gave to each man in the camp.

These Canwayawapi or counting sticks were used to determine the number of men in the camp. Each man painted his stick red with iron oxide if he was without war honors, and black with charcoal if he had war honors.

These counting sticks were later used to keep score in the Moccasin Game, which was played to while away the time waiting for the scouts to return.

The ten Honored Men selected four marshals called Akicita to keep order, selecting one as the leader Akicita Itancan. These men were the enforcers of the orders given by the ten chiefs.

These men wore black stripes on their face to show who they were, distinguishing themselves from the others. They were very strict in carrying out their duties.

Any man disobeying the chief’s orders were Akicita kte or Soldier Killed, meaning the offender was punished by being whipped, his horse or dog killed, bow and arrows or gun stock broken, all depending on the severity of the offence.

Sometimes they even cut up his tent and broke the poles. This action was a double punishment as the lodge was owned by his wife, which would bring down upon him his wife and in-laws wrath. The Akicita even had authority over the Ten Hunt Leaders, all the camp was under their jurisdiction.

A Eyanpaha or Camp Crier was selected to circuit the camp making known the decisions of the ten chiefs.

Most times the individual selected as Announcer was known by everyone as the best man for the job. Naturally he had to have a strong-loud voice to be heard as he circled the camp repeating the commands.

To act as servants or waiters to the Tiyotipi; two virgin boys were selected called Wayuţaŋpi Touchers, who bring the firewood, cook and serve the food, and perform the sundry of duties required to keep the council tent running smoothly.

Dale Perkins, student in Louie Garcia’s carpentry class at Cankdeska Community College, Fort Totten, ND , shows his handmade project, a 4-drawer chest of drawers. Photo courtesy of author.

The fire in the Council tent was kept continually burning.

Two scouts Tuŋweyapi were now appointed. According to Rev. Riggs one was called Wakcanya or locator, and the other Wayeya One Sent.9

The scouts were selected from the best families, known for their dedication to duty. The relatives of all who were selected gave away to the poor for this great honor.

The two scouts were each given a wolf skin as a badge of office, with great ceremony. The head of the wolf was tied on their heads being secured by a thong around the chin. The wolf’s body hung down their back. The wolf hide was worn so as not to alarm the buffalo if they were detected.

Song of Departure

Eca ozuye kinhan (In war usually)

Tuweniwalakeŝni ca (I will never be seen)

Bliheiçiya waun welo. (I do the best I can).10.

The two scouts scattered out going in separate directions. Sometimes they were out twelve days before they found the herd.

If as it happened on occasion, they found nothing, they sulked back to camp attracting as little attention as possible.

The scouts looked for Tumble Bugs also known as ground beetles whose horns always pointed towards the buffalo. The large grass hopper was also a sign buffalo were near.

As soon as the scouts departed, the camp moved to the next predetermined camp location. As the general direction was known to all, the returning scouts could easily find the camping location.

Justin Azure stores computer equipment and supplies in the bookcase he made in carpentry class at Cankdeska Community College. Photo courtesy of author.

As soon as the scout was sighted in the distance and by his movements indicated that a pteoptya (herd) was sighted, the people became excited. A long stick was planted in front of the Tiyotipi or a pile of buffalo dung.

The camp leader painted himself red all over. Two lines of men assembled in front of the Tiyotipi with the ten chiefs seated within.

All was now ready. As the scout came near he ran in a zigzag pattern, calling out “Co-o, co-o.” He ran between the two lines of men and kicked over the stick or scattered the buffalo dung.

As he arrived at the Tiyotipi whose cover was pulled to the side so all could see inside; the ten seated chiefs raised their open hands and placed their palms on the ground crying hi-hi.

The hunt leader rose and taking his pipe placed a pinch of powdered buffalo dung on top of the tobacco in the pipe bowl. He lit the pipe with a coal from the fire and prayed to the four directions thanking God for the scouts find.

After the pipe was puffed on by the scout it was passed to the other nine hunt chiefs. A second pipe is presented in the same manner as the first.

Being presented with two pipes to smoke was an admonition to the scout to Wowicaķeya, truthfully report his discoveries.

The scout made his report as to the number and location of the herd, with his clenched fist and protruding thumb he pointed to the herd’s direction. This method of pointing with the thumb was the sign for a buffalo in the sign language11.

Based on the information the hunt leaders then had to decide their course of action. If the scout reported only a small herd after days of scouting, they may choose to send the scouts out again12.

After a decision is made the Announcer was instructed to announce to the people that a herd was found and to prepare to move camp as directed.

A typical announcement:

Aķin iyakaŝka (Saddle Bind)

Śiçeca teĥike (Children dear)

Anpetu Hankeya (Half a day)

Ecawaĥan kta ce. (I will kill).13

The camp was in a jovial mood and buffalo hunting songs were heard though out the camp14. Their prayers to God had been answered.

The camp was moved to a great distance from the herd, so as not to alarm them.

The Akicita gathered the hunters, giving them instruction and selecting those who would go with the two designated groups.

The hunters often rode a common horse, but switched to a trained horse used mostly for buffalo hunting. These horses were trained to run next to a fleeing buffalo.

Sometimes women would follow at a distance to assist in the butchering. With the scouts in the lead, the hunters approached in two arcs, one on each side with a gap in the middle, but to the rear down wind from the herd.

The hunt was usually started very early in the morning. Once the hunters were in position, all waited for the signal.

Sometimes a hunter may rush forward in his excitement upon seeing the herd. This action would start the buffalo to stampede before everyone was ready and the success of the hunt would be in jeopardy.

If all was lost, the offender would be whipped, and horse and hunting equipment destroyed right on the spot by the Akicita. Everyone knew the rules, the hunters kept their places until the prearranged signal was given.

At the signal, such as a blanket being waved from a visible location, the two arcs of hunters rushed forward. The hunters were primarily interested in the cows’ pte, especially two-year-olds. They were the easiest to tan into robes and tents.

The bulls Tatanka ran on the outside protecting the cows and calves ptehinzicana.

The weapon of choice is the bow and arrow, but the lance was also employed. Each hunter had identifiable colors and marks on their arrows; it was easily made known who made the kill.

The hunter would ride next to the cow and shoot an arrow behind the shoulder blade into the heart. He then rushed on to the next prey.

This was very dangerous work as the buffalo could turn and gore the horse, unseating the hunter to be injured or trampled to death by the fleeing buffalo.15

Young men who were inexperienced would trail behind killing the strays. Young boys on their first hunt would chase after the calves.

Their first kill was celebrated by the family to honor the young hunter and encourage him for future exploits. This honoring continues today on the reservation with the first deer and first fish celebrations.

Once the buffalo disappeared in the distance, the men began to locate their kills.

One tradition of the men was to remove the liver, squeeze some gall on it and eat it raw.

Old men who were unable to hunt anymore brought up the common horses to transport the hides and meat back to the camp. The hunters usually gave these old men a buffalo or part of one to honor them for their service to the people.

The men proceeded to butcher their kill until their wives could arrive to help.

The buffalo were butchered in a prescribed age-old way, learned from hundreds of years of experience. The method of butchering is described by Heĥakawakita (Looking Elk) from the Standing Rock Reservation.16

As the pack horses began to arrive in camp, the processing of the meat was begun.

The hides were staked out to dry, the meat cut into thin strips called Papa, to be dried for future use.17

Cooking fires were all ablaze for everyone wanted fresh meat.

Fresh meat was brought to the Tiyotipi to feed the ten chiefs. The two boys cooked the meat and served the meat in a special way.

A piece of cooked meat was impaled on a pointed stick and Wiyohnagwicakiya and placed into the mouth of each chief who gave thanks.

Once this ceremony was performed everyone could eat the freshly cooked meat.

Several days were required to process the buffalo. Usually some of the dried meat was deposited into cache pits to be saved for future use.

The tons of fresh meat had been dried, reduced to a trifling of the former weight dubbed Jerky.

Mostly the meat was made into Wasna (Pemmican) by pounding the dried meat into a powder and mixing it with dried Chokecherry, or June berries.

The mixture was then encapsulated in fat rendered from the marrow of the buffalo bones. The meat processed in this manner would last for years.

A number of years ago a cache of meat was discovered in the Pembina Hills and deemed safe to eat after 150 years.

The sacks of pemmican were placed into grass lined, bell shaped cache pits, its location hidden to all but the owner.18, 19, 20

Grass Dance of the Spirit Lake Dakota, written by Louis Garcia, was published by Cankdeska Community College. Available from the college bookstore.

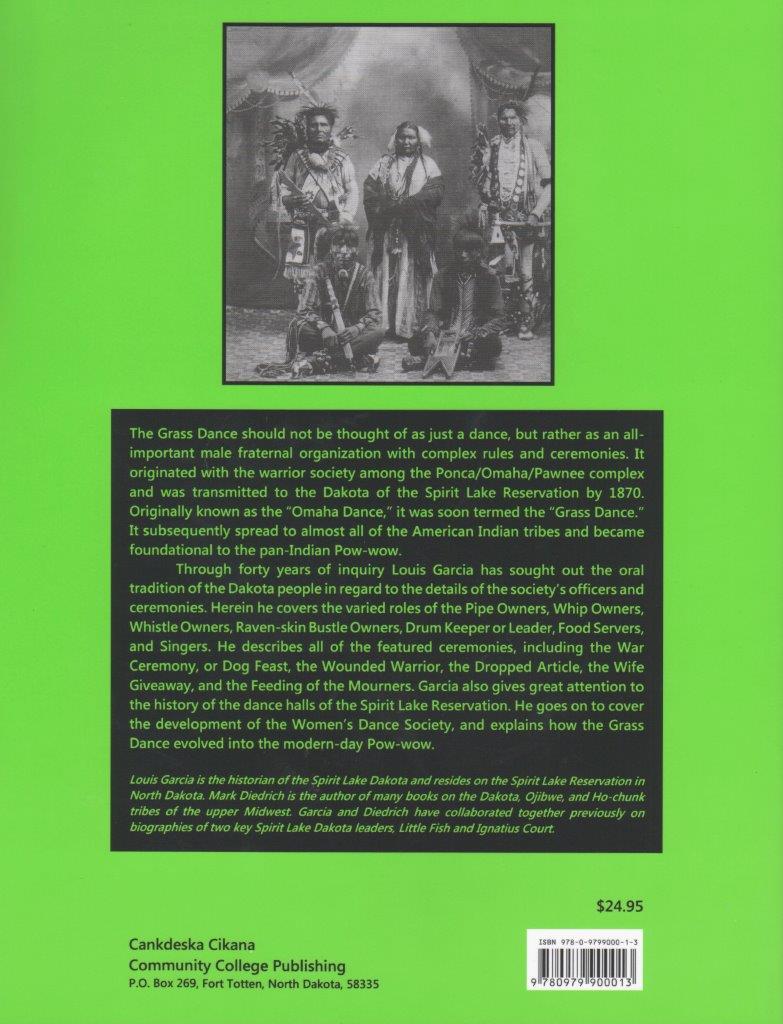

Back cover of book Grass Dance of the Spirit Lake Dakota by Louis Garcia. Photos courtesy of author.

Glossary

Akicita – Policeman, soldier, enforcer, sergeant at arms.

Akicita Itancan – Police Chief (Itancan=leader, captain).

Akicita Kte – Punishment by the police, Soldier Killed (Kte=to kill).

Buffalo Hunt – The last hunt of 1882 (Wableza=Inspector; Lakota= Sioux; Ob=both; Wanasapi=buffalo hunt; Waniyetu=winter time). By winter they are referring to the year in which the event occurred. The hunt actually happened in the summer. 5,000 buffalo were killed.

Cannahma Wakpala – HiddenWood Creek, (Can=wood; Nahma=to hide; Wakpala=creek in the Lakota dialect). Named Flat Creek by the railroad because the area is quite flat (Berg). Riviere du Bois Cache of the Métis. The creek is 50 miles long, rising in North Dakota and flowing southeast to join the Grand River a few miles below the junction of the north and south branches in Perkins County, South Dakota.

Canwayawayapi – Counting sticks (Can=wood, stick; Wayawa=to count: Yapi=causative).

Cokayata – The center of the camp circle. (Cokaya=center; [A]ta= at the). Eyanpaha Announcer, camp crier, speaker (Eyan=speak to; Paha= hill) meaning his voice had to be so loud it would reach the distant hills.

Papa – Dried meat, jerky. In modern times this treat is mixed with sugar.

Park – an enclosure in the shape of a keyhole, two wings allow the buffalo to be driven in and the gate closed. This is the origin of the name Park River, a western tributary of the Red River of the North located in Walsh County, North Dakota.

Ptehinzicana – Buffalo calf (Pte=cow; hin=hair; Zica=yellow like; Na=familiarity). A calf is a buffalo with yellow like hair. Sometimes pronounced as ptehincana.

Pteoptaye– Buffalo Herd (Pte=cow; Optaye=herd). The general name for buffalo in Indian is a cow—Pte, not as usually stated Tatanka (Ta=ruminating split toe animals; Tanka, =big, large) which means the bull.

Tiyokeheya– Enlargement of the council tent by joining two or three tents together. Ti=tent; [I]yokeheya=add to, an addition)

Tiyotipi – The Council Tent, the dwelling place of the council in the center of the camp circle. The tent of tents. (Ti=house, tent; Yo=in, at, on; Tipi=dwelling).

Tuŋweyapi – Scouts, spies (Tuŋweya=scout; Pi=plural).

Wakcanyan – Locator, Reporter.

Wanasapi – Buffalo Hunting (Wanasa=buffalo hunt [probably a contraction]; Pi=plural).

Wasna – Powdered meat, fruit and grease mixed together, commonly referred to as Pemmican.

Wayacopi – Judges (Wa=noun marker; yaco=to judge; Pi=plural).

Wayeya – Hunt, seeker.

Wayutaŋpi – Waiter, food touchers (Wa=noun marker; Yutaŋ=to touch; Pi=plural) two virgin boys.

Wicaŝtayataŋpi – Hunt and war chiefs, ten men were selected (Wicaŝta= man; Yataŋ=to praise; Pi=plural. There was no one who was the chief of the tribe. This change in government came during the treaty making era with the United States government.

Wiyohnagwicakiya – Put food into the mouth. (W[o]=abstraction; I=mouth; Yo =in, at, on; Hnag [contraction of hnake] to place; Wica= them; Kiya=causative).Wowicaķeya = Truthfully, factually.

Bibliography

1.Deloria, Vine Junior . Singing for a Spirit: A Portrait of the Dakota Sioux. Santa Fe: Clear Light Publishers 1999, p115.

2.Catlin, George. Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Conditions of the North American Indians. Volume One. New York: Dover Publications 1973, Plate 110.

3.Cowdrey, Mike; Martin, Ned and Jody. Horses, Bridles of the American Indian. Nicasio, CA: Hawk Hill Press 2012, 14-15.

4.Koucky, Rudolph W. M.D. The Buffalo Disaster of 1882. North Dakota History 50 (1) 1983: 23-30

5.Berg, Francie M. Buffalo Heartbeats Across the Plains. Dakota Buttes Visitors Council, Hettinger, ND 2018, 68. When homesteader RM Bunn wrote of his disease theory, upon finding a cluster of old whitened buffalo bones, President TR Roosevelt wrote to him: “I am very sorry not to agree with your reasoning. I was an eye-witness to the extermination of the buffalo. It was due to the number of hunters—partly by red men but chiefly by the whites. Nothing else was any real factor. The man with the rifle was the sole, appreciable, active factor.”

6.Berg. Buffalo Heartbeats, 2028, 55. The last 1,200 wild buffalo were slaughtered Oct. 12 and 13, 1883, by Sitting Bull and his band on the Great Sioux Reservation in what is now South Dakota, according to William Hornaday in his 1889 book The Exterimination of the American Bison.

7.Densmore, Frances. Teton Sioux Music Bulletin 61. Smithsonian Institute, Bureau of American Ethnology. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Printing Office 1918: 436-447.

8.Berg. Buffalo Heartbeats, 2018, 10-25. The Great Hiddenwood Hunt. Also personal communication, 2005.

9.Riggs, Stephen R. Dakota Grammar, Texts, and Ethnography. Minneapolis: Ross and Haines, Inc 1973: 200-202.

10.Densmore, 108.

11.Clark, W. P. The Indian Sign Language. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 1982:83.

12.Densmore, 441.

13. Riggs, 202.

14.Densmore, 440-442.

15.Catlin 26, Plate 9; 254, Plate111.

16.Densmore, 443-444.

17.Laubin, Reginald, Laubin, Gladys. The Indian Tipi: its History, Construction, and Use. Norman; University of Oklahoma Press 1977: 150.

18. Gilman, Carolyn, Mary Jane Schneider. The Way to Independence: Memories of a Hidatsa Indian Family 1840-1920. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press 1987: 19, 22.

19. Koucky. Old Names for Buffalo Meat, North Dakota History 50 (4) 1983: 16, 17.

20.Wilson, Gilbert L. Agriculture of the Hidatsa Indians: An Indian Interpretation. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press 1987. Lowie, Robert H. Dance Associations of the Eastern Dakota. New York: American Museum of Natural History 1913: 132-137. McLaughlin, James. My friend the Indian. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company 1926: 97-116. Olden, Sarah Emilia. The People of Tipi Sapa: The Dakotas. Milwaukee: Morehouse Publishing Co. 1918: 97-104. Standing Bear, Luther. My People the Sioux. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 1975: 49-66. Land of the Spotted Eagle. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 1978: 76-78.

Louis Garcia

Guest Blog from Tokio, ND