Buffalo resting in the junipers at Teddy Roosevelt National Park, ND. Credit National Park Service.

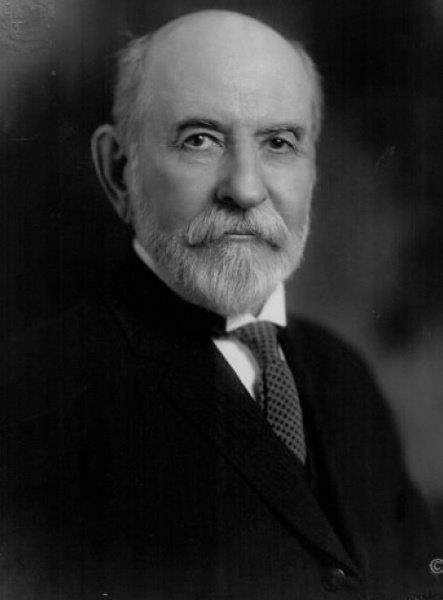

William Hornaday published his amazing report on the slaughter of the buffalo herds in a government book in 1889, which he titled The Extermination of the American Bison.

It was intended to be the last word on bison.

William Hornaday hunted buffalo in remote canyons of central Montana, shot, killed and mounted his large, majestic bull with its family of six for the Smithsonian—which became an icon for the nation–wrote his amazing book on how buffalo were being exterminated, and then devoted the rest of his life to saving live buffalo in Parks and wildlife refuges throughout the country. Photographer unknown.

Determined to get it right, he spared no effort in contacting every possible source of buffalo knowledge, from Army officers at far-flung western forts to fur traders, railroaders, hide hunters and cowboys.

He learned that the end of the big herds came in Dakota Territory—on the Great Sioux reservation—but offered few details. Except to state that Sitting Bull and his band were there at the end.

He soon discovered that small herds of buffalo here and there were not only surviving—but thriving and multiplying.

Upon publishing his greatest book—on extermination of the buffalo—Hornaday could have rested on his laurels, but fortunately for us, he did not.

Instead, he spent the rest of his life fighting for the conservation of healthy, live buffalo.

No longer solely interested in carcasses, he developed a vision for living buffalo—a way they could be kept safe in parks and public lands across America.

He had a new mission—to save buffalo and other game animals in refuges where they could live out their lives in safety.

In Washington, DC and New York he lectured and wrote impassioned articles on the need to set aside national reserves for buffalo and other wildlife.

But Congress did not act.

In no uncertain terms, Hornaday expressed his anger and despair.

“We are weary of witnessing the greed, selfishness and cruelty of ‘civilized’ man toward the wild creatures of the earth. We are sick of tales of slaughter and pictures of carnage.

“It is time for sweeping reformation; and that is precisely what we now demand,” he wrote.

“If the majority of the people of America feel that so long as there is any game alive there must be an annual two months or four months open season for its slaughter, then assuredly we soon will have a game-less continent.”

A gameless continent! A sobering thought indeed.

Yet, the west teemed with wildlife and the risk of that seemed impossible.

Westerners generally opposed laws to restrict hunting, knowing many desperate pioneers on the frontier survived by hunting and selling hides and meat.

Congress shrugged the conservation concerns aside.

As for using public land for grazing buffalo, that was highly unlikely when the public clamored for even more homestead land.

As an early leader in conservation and the passionate editor of Field and Stream Magazine Grinnell, too, played an important role in influencing the saving of buffalo in America.

An early conservation writer, George Bird Grinnell earned his PhD and editorship of Field and Stream Magazine, after first joining the Pawnee’s in their last great buffalo hunt of 1872 while still in college. Credit William Notman, c 1880.

George Bird Grinnell wrote often about the need for saving the buffalo.

Born in Brooklyn, New York, Grinnell lived in Audubon Park and had connections with the Audubon family, which likely helped spur his interest in the natural world.

Like fellow conservationists Hornaday and Theodore Roosevelt, Grinnell had a special interest in the west.

Like them he hunted buffalo and in fact, had joined the Pawnee’s last great buffalo hunt of in 1872 while still in college.

He rode with General Custer’s 1874 Black Hills expedition and the next year went with Col. William Ludlow’s expedition to Yellowstone Park.

For the Ludlow report he documented the poaching of buffalo, deer, elk and antelope that was going on in Yellowstone.

Grinnell earned a PhD from Yale in 1880, where he was already an editor of Field and Stream Magazine. He continued his long-term career as senior editor and publisher of that magazine.

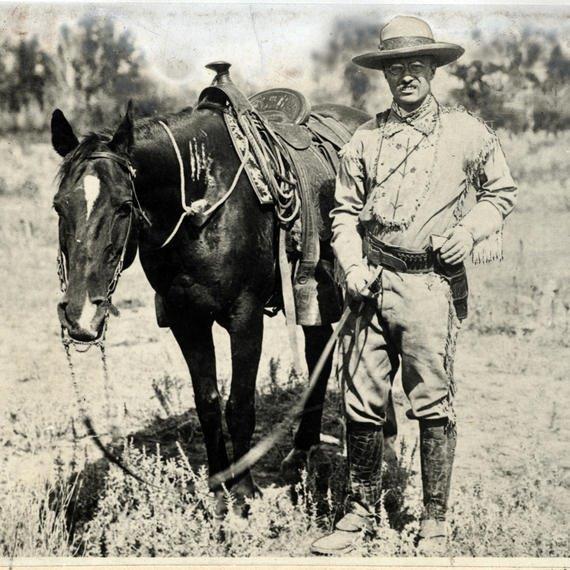

On his western ranch Theodore Roosevelt—who came to Dakota in 1883 to hunt big game and stayed to set up a ranch business—soon realized that the elk, bighorn sheep and buffalo that he so admired would not survive relentless overhunting or the destruction of their grasslands under modern civilization.

A frail asthmatic child, Theodore Roosevelt learned hard-riding cowboy ways on his badlands North Dakota ranch and built up his strength and endurance. He hunted big game and grew convinced of the need to preserve all forms of wildlife.

He became increasingly convinced of the need to protect the magnificent buffalo and provide large, safe places for them to live.

When the long and bitterly cold winter of 1886–1887 wiped out his herd of cattle and those of other ranchers, and with them over half his $80,000 investment, Roosevelt returned to the East.

The badlands of Theodore Roosevelt National Park after a rain, at sunset—rugged ridges, clay banks and fertile green bottomlands. Good ranching country. NPS.

After that disastrous winter, he let go of most of his ranch holdings but continued to maintain some cattle interests in the badlands.

In 1886, after his first wife’s death, Roosevelt married Edith Carow, a childhood friend.

He entered politics—first as a delegate to the Republican National Convention, then president of the NY City Board of Police Commissioners, and next as governor of NY where he battled corruption and fought for reform.

He launched the rules for his Square Deal: “Honesty in public affairs, an equitable sharing of privilege and responsibility, and subordination of party and local concerns to the interests of the state at large.”

Appointed assistant secretary of the navy by President William McKinley, Roosevelt worked for a stronger navy and railed against Spain for its interference in Cuba and North American affairs.

When war with Spain was declared in 1898, Roosevelt organized the Rough Riders and was sent to fight in Cuba. The successful charge of the Rough Riders up Kettle Hill July 1, 1898, during the deadly Battle of Santiago was well publicized and made him a national hero.

TR became Vice President of the United States in 1901—a powerless office. However, he gave one memorable speech at the Minnesota State Fair.

“I have always been fond of the West African proverb,” he told the crowd. ‘Speak softly and carry a big stick—you will go far.’”

The cartoonists picked up on his “big stick.”

It was a hint of the style he would soon put into practice. Within six months he was President, upon the assassination of William McKinley.

He continued to visit western North Dakota to hunt, renew himself and refresh his soul in the badlands, where he said “the romance of my life began.”

The American Bison Society

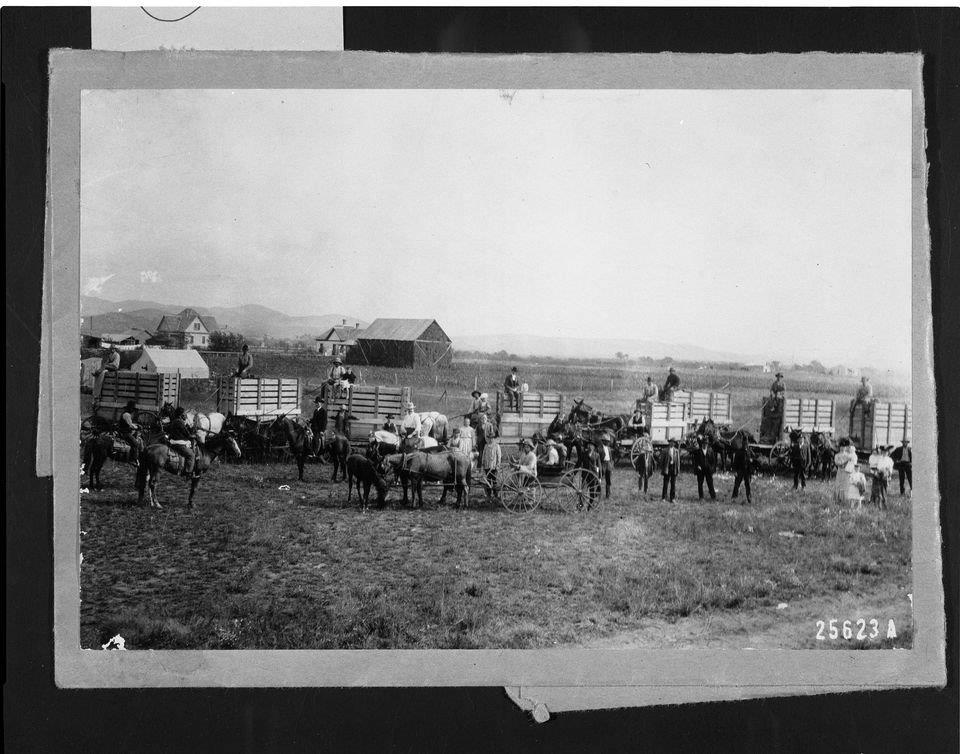

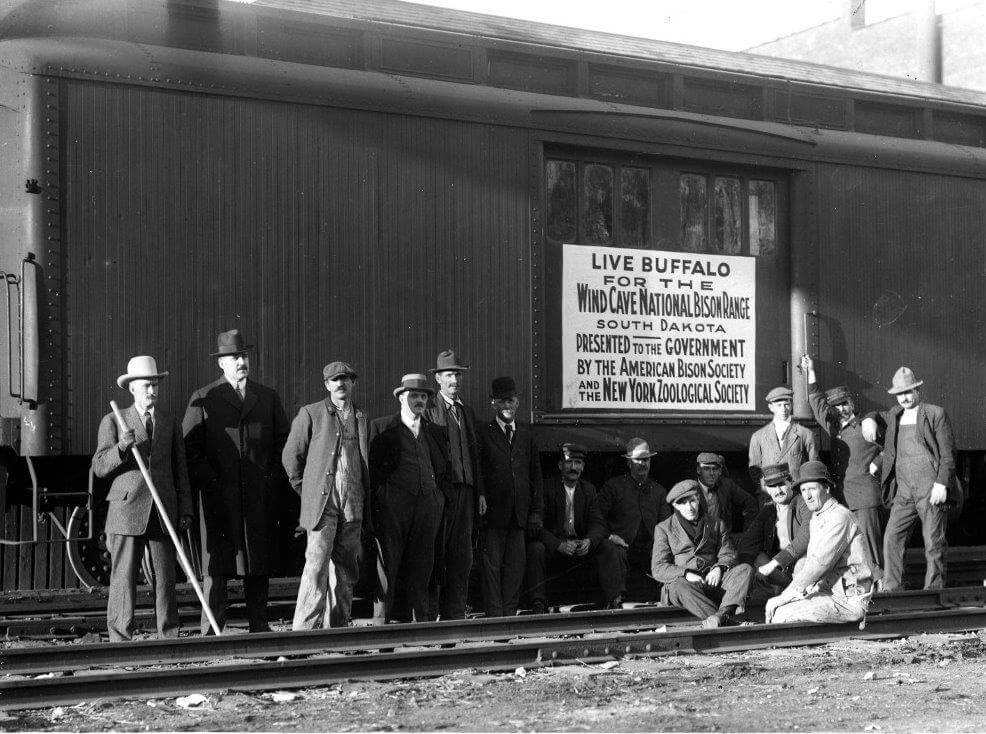

The American Bison Society arranged a donation of bison from the New York Zoological Society to the new Wichita National Forest and Game Preserve in Oklahoma. On Oct 11,1907, 15 of “the finest buffalo from the New York Zoological Park were shipped by rail to Oklahoma.’ Here the six bulls and nine cows were being safely returned to the plains and mountains of Oklahoma. Credit US FWS Archives.

Grinnell founded the Audubon Society of New York, and organized the New York Zoological Society. He wrote articles against market hunting and in favor of realistic game laws.

With Theodore Roosevelt he founded the Boone and Crockett Club, dedicated to the restoration of America’s wildlands. Together he and Roosevelt wrote the club’s first book in 1895.

For 35 years, until 1911, Grinnell had an ideal platform in Field and Stream for publicizing his passion on conservation and environmental issues.

Grinnell took hunting trips to what is now Glacier National Park in Montana, with the well-known guide James Willard Schultz.

In a 1885 visit they hiked over the St. Mary Lakes region naming outstanding features including the glacier named for him—Grinnell Glacier.

These experiences spurred him to write many articles urging protection of the buffalo and the American West. He spent many years studying the natural history of the region.

He was influential in establishing Glacier National Park when the park system began in 1910.

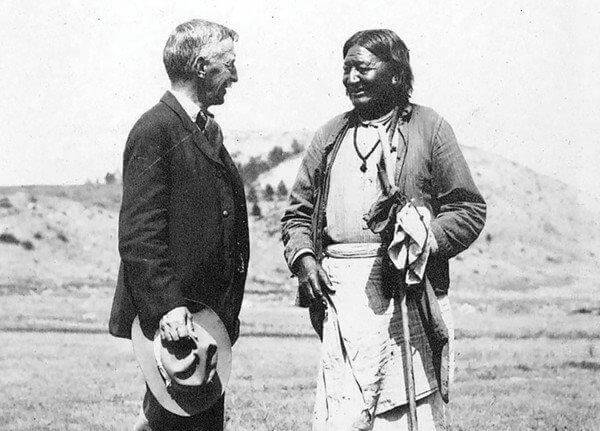

Grinnell also took a deep interest in Native Americans.

On his many trips west, he often lived with Indian tribes and became an advocate for them in the East. He wrote many books on the Native Americans, some of the most popular on the Cheyenne, the Pawnee and the Blackfeet. Also Blackfeet Indian Stories, When Buffalo Ran, and Native American Ways: Four Paths to Enlightenment

As a young man Grinnell lived with and became a friend of several Indian tribes. Later he became an advocate for them.

Then Hornaday discovered an amazingly effective route to his conservation goals.

The idea came on a lecture tour, when a listener asked, “Why not form a society dedicated to the permanent preservation of the buffalo?”

Americans could be mobilized for a cause, as Henry Osborn, president of the New York Zoological Society, wrote in his foreword to William Hornaday’s new book, Our Vanishing Wildlife:

“Americans are practical. Like all other northern peoples, they love money and will sacrifice much for it, but they are also full of idealism, as well as moral and spiritual energy.

‘The influence of the splendid body of Americans and Canadians who have turned their best forces of mind and language into literature and into political power for the conservation movement, is becoming stronger every day.”

Hornaday passed the idea on to the new president, who often voiced his regrets at the state of conservation in his country.

“The extermination of the buffalo has been a veritable tragedy of the animal world,” Theodore Roosevelt said.

In his message to Congress on Dec 5, 1905, the Conservation President Teddy Roosevelt called for a buffalo refuge.

“The most characteristic animal of the western plains was the great shaggy-maned wild ox, the bison, commonly known as buffalo.

“Small fragments of herds exist in a domesticated state, here and there. Such a herd as that on the Flathead Reservation should not be allowed to go out of existence.

“Either on some reservation or on some forest reserve or refuge, provision should be made for the preservation of such a herd.”

At last, a president who understood both buffalo and ranching—from his time as a western rancher—and with a heart for conservation!

Three days later, on Dec. 8, the American Bison Society was born, with William Hornaday as president and Roosevelt, honorary president.

Memberships poured in and suddenly Hornaday had the power he wanted.

He immediately proposed a federal range—on or next to the Flathead Indian Reservation in western Montana, where Michel Pablo still ran his half of the original Walking Coyote herd.

Within six months Congress appropriated money to enclose 8,000 acres of the National Wichita Forest Reserve in southwest Oklahoma with a high wire fence for a wildlife refuge and stocked it with 15 donated buffalo.

One of the first wildlife parks to get buffalo was the National Wichita Forest Reserve in southwest Oklahoma, stocked with 15 donated buffalo.

By 1909 the US government owned 158 buffalo.

Most were in Yellowstone National Park, along with 40 head on the National Bison Range, 19 on the Wichita Game Reserve in Oklahoma, and 7 in the National Zoological Park in Washington, DC.

Fourteen Buffalo donated to Wind Cave National Game Preserve in the Black Hills, SD, leave New York City after a send-off by men of the American Bison Society. Credit Wildlife Conservation Society.

The American Bison Society stocked Wind Cave National Game Preserve in the Black Hills with 14 buffalo, surprisingly from the New York City Zoo, and later added six from Yellowstone Park.

This remains a special herd that tests genetically pure because of its unique origins.

Grinnell founded the Audubon Society of New York, and was an organizer of the New York Zoological Society.

He was a founding member, with Theodore Roosevelt, of the Boone and Crockett Club, dedicated to the restoration of America’s wildlands. Together he and Roosevelt wrote the club’s first book in 1895.

Buffalo arriving at the Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge in Colorado. NPS.

He campaigned intensely against market hunting and for realistic game laws and was influential in the enactment of the Migratory Bird Treaty in Great Britain in 1916 as well as the adoption of strong regulatory control of hunting in all states.

Hornaday came up with another startling new idea that took root: Forever prohibit the sale of wild game.

Another federal herd of six donated buffalo, launched in the Appalachian Mountains near Asheville, North Carolina, failed to grow. The last lone buffalo died there a couple of decades later.

The Teddy Roosevelt Legacy

Perhaps spurred on by the popularity of their successes with the American Bison Society, President Theodore Roosevelt wielded his “big stick” and went on to establish numerous wildlife refuges stocked with buffalo and teeming with wild animals and bird life.

As president—from 1901 to 1909—he became one of the most powerful voices in the history of American conservation.

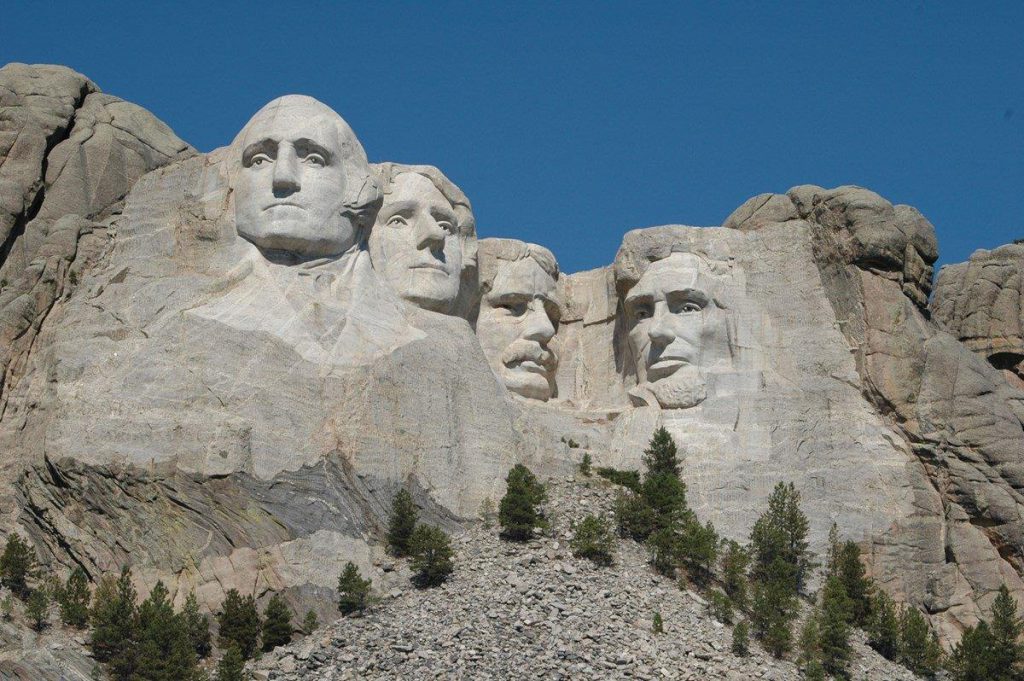

Roosevelt set aside almost five times as much land as all of his predecessors combined, and earned himself a place on Mt. Rushmore as this country’s greatest conservationist, along with three of its greatest leaders, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln.

Teddy Roosevelt earned his place on Mt. Rushmore as the Conservation President. NPS.

The Park System grew rapidly. When the National Park Service was created in 1916—seven years after Roosevelt left office—there were 35 sites to be managed by the new organization. Roosevelt helped create 23 of those.

He took the view that the President as a “steward of the people” should take whatever action is necessary for the public good unless expressly forbidden by law or the Constitution.

“I did not usurp power,” he wrote, “but I did greatly broaden the use of executive power.”

When it came to setting aside land and resources for use of the general public he did not hesitate. He said:

”We have become great because of the lavish use of our resources.

“But the time has come to inquire seriously what will happen when our forests are gone, when the coal, the iron, the oil, and the gas are exhausted, when the soils have still further impoverished and washed into the streams, polluting the rivers, denuding the fields and obstructing navigation.

“We have fallen heirs to the most glorious heritage a people ever received, and each one must do his part if we wish to show that the nation is worthy of its good fortune.”

After becoming president, Roosevelt:

- Created the United States Forest Service (USFS) and established

- 150 national forests

- 51 federal bird reserves

- 4 national game preserves

- Set aside 230 million acres of public land

National parks are created by an act of Congress. Roosevelt worked with his legislative branch to establish these 5 parks:

- Crater Lake National Park (OR) – 1902

- Wind Cave National Park (SD) – 1903

- Sullys Hill (ND) – 1904 (now managed by USFWS)

- Platt National Park (OK) – 1906 (now part of Chickasaw National Recreation Area)

- Mesa Verde National Park (CO) – 1906

- Also added land to Yosemite National Park (CA)

- Named for him is Theodore Roosevelt National Park (1978)

in the badlands of North Dakota, where he owned two cattle ranches

and where his Presidential Library is scheduled to be built soon.

Since he did not need congressional approval for national monuments, Roosevelt could establish them much easier than national parks. He dedicated these 18 sites as national monuments:

- Devil’s Tower (WY) – 1906

- El Morro (NM) – 1906

- Montezuma Castle (AZ) – 1906

- Petrified Forest (AZ) – 1906 (now a national park)

- Chaco Canyon (NM) – 1907

- Lassen Peak (CA) – 1907 (now Lassen Volcanic National Park)

- Cinder Cone (CA) – 1907 (now part of Lassen Volcanic National Park)

- Gila Cliff Dwellings (NM) – 1907

- Tonto (AZ) – 1907

- Muir Woods (CA) – 1908

- Grand Canyon (AZ) – 1908 (now a national park)

- Pinnacles (CA) – 1908 (now a national park)

- Jewel Cave (SD) – 1908

- Natural Bridges (UT) – 1908

- Lewis & Clark Caverns (MT) – 1908 (now a Montana State Park)

- Tumacacori (AZ) – 1908

- Wheeler (CO) – 1908 (now Wheeler Geologic Area, part of Rio Grande National Forest)

- Mount Olympus (WA) – 1909 (now Olympic National Park)

Roosevelt also established Chalmette Monument and Grounds in 1907, site of the Battle of New Orleans, now part of Jean Lafitte National Historical Park.

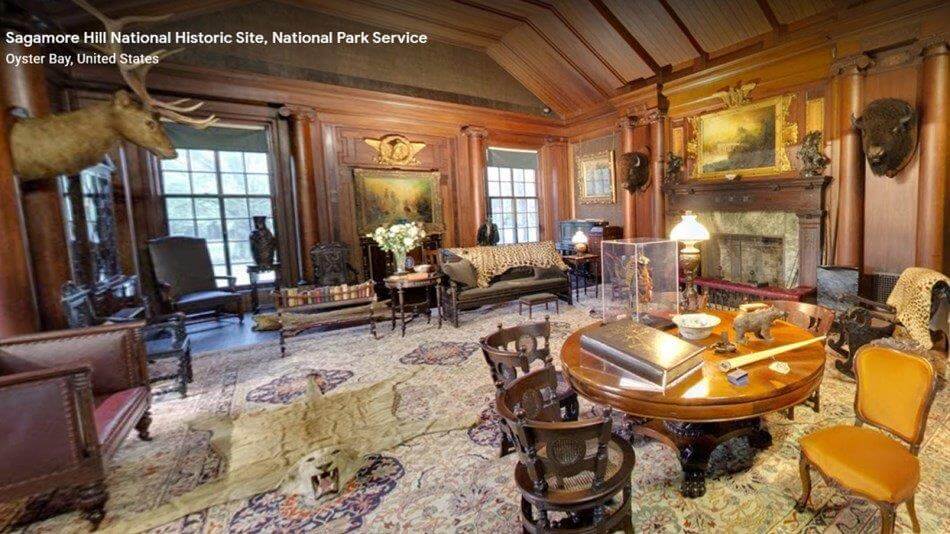

Sagamore Hill, New York, was the home of Theodore Roosevelt and his family from 1885 until his death in 1919. Called his “Summer White House,” during his time in office it is now a Historic Site with 83 acres of park grounds and historic buildings. NPS.

TR’s words and actions continue to affect how we approach and appreciate the natural world.

Though his many writings describe numerous hunting trips and successful kills, they are filled with his regret for the loss of species and habitat. He wrote:

“It is also vandalism wantonly to destroy or to permit the destruction of what is beautiful in nature, whether it be a cliff, a forest, or a species of mammal or bird.

“Here in the United States we turn our rivers and streams into sewers and dumping-grounds, we pollute the air, we destroy forests, and exterminate fishes, birds and mammals—not to speak of vulgarizing charming landscapes with hideous advertisements.

“But at last it looks as if our people are awakening.”

Today, Theodore Roosevelt’s legacy is found across the country.

His words and actions continue to affect how we approach and appreciate the natural world.

He saw the effects of overgrazing, and suffered the loss of his ranches because of it.

Here in North Dakota, where many of his personal concerns inspired his later environmental efforts, Roosevelt is remembered with a national park that bears his name and honors the memory of this dedicated conservationist.

Roosevelt continued to maintain some cattle interests in the badlands until he became Vice President of the United States in 1901.

For the rest of his life he continued to visit good friends he made in the badlands and to enjoy the renewal and inspiration—and what he called the ‘hardy life’—he found here.

“I have always said I would not have been President had it not been for my experience in North Dakota.

“It was here that the romance of my life began.

“I grow very fond of this place, and it certainly has a desolate, grim beauty of its own, that has a curious fascination for me.

“There is a delight in the hardy life of the open. There are no words that can tell the hidden spirit of the wilderness that can reveal its mystery, its melancholy and its charm.

“The Bad Lands grade all the way from those that are almost rolling in character to those that are so fantastically broken in form and so bizarre in color as to seem hardly properly to belong to this earth.

“Nothing could be more lonely and nothing more beautiful than the view at nightfall across the prairies to these huge hill masses, when the lengthening shadows had at last merged into one and the faint after-glow of the red sunset filled the west.”

At age 42 TR also expanded presidential power for support of the public interest in conflicts between big business and labor.

Although he promised continuity with McKinley’s policies, he transformed the public image of the presidency at once.

He led the nation toward an active role in world politics, particularly in Europe and Asia.

Theodore Roosevelt riding with others into Yellowstone Park from the train station in Gardiner, MT. NPS.

Roosevelt wielded his big-stick diplomacy in 1903, when he helped Panama pull away from Colombia and gave the United States a Canal Zone.

He secured the route and began construction of the Panama Canal (1904–14). In 1906 Roosevelt visited the Canal–the first president to leave the US while in office.

He reached an agreement on immigration with Japan, and sent the Great White Fleet on a goodwill tour of the world.

He won the Nobel Prize for Peace (posthumously) for mediating an end to the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905).

He renamed the presidential home “the White House” and opened its doors to entertain an array of people who fascinated him—cowboys, prizefighters, explorers, writers and artists.

He gained the respect and affection of ordinary working Americans everywhere despite his wealthy upbringing.

His refusal to shoot a bear cub tied to a tree on a 1902 hunting trip inspired a toy maker to name a stuffed bear after him—and a teddy bear fad swept the nation.

The North Room in TR’s Sagamore Hill home at Oyster Bay displays his buffalo head, his hunting skills and love for the natural world, along with a touch of elegance. NPS.

TR and Edith lived all their adult lives at Sagamore Hill, an estate near Oyster Bay, Long Island. They had five children: Theodore, Jr., Kermit, Ethel, Archibald, and Quentin.

The Roosevelt family with Theodore and Edith seated in front; oldest daughter Alice, center back. NPS.

His young children played on the White House lawn—along with TR himself at times. The marriage of his oldest daughter Alice in 1905 to Representative Nicholas Longworth of Ohio became a major social event.

Always the reformer, Roosevelt gave speeches from the presidency’s “bully pulpit,” aimed at raising public consciousness about the nation’s role in world politics, the need to control the trusts that dominated the economy, the regulation of railroads and the impact of political corruption.

He appointed young college-educated men to administrative positions.

“While President, I have been President,” he said. “Emphatically; I have used every ounce of power there was in the office . . . “

“I do not believe that any President ever had as thoroughly good a time as I have had, or has ever enjoyed himself as much.”

Roosevelt’s last visit to the North Dakota badlands came in the fall of 1918, just a few months before his death January 6, 1919 at the age of 60, in Oyster Bay, New York.

His Presidential Library begins construction in 2021 within the borders of Theodore Roosevelt National Park in the badlands, where his two ranches—the Maltese Cross and the Elkhorn—were located.

Who Really Saved the Buffalo?

So who really did save the buffalo?

William Hornaday took special delight in the new buffalo refuge in western Montana when it was finished with its magnificent view of the snow-packed Mission range.

At last his wildest dreams had come true.

“It is beautiful and perfect beyond compare,” he marveled.

Indeed. It is perfect!

There, in the shadow of the Rockies, buffalo still graze across the open grasslands of Montana’s beautiful Flathead Valley, rising in the stunning foothills and narrow canyons of what the Natives call Red Sleep Mountain to the high Missions beyond.

Big Medicine, the famous white buffalo, was born there and lived out his 26 years on the National Bison Range.

The refuge is kept as a natural, controlled ecosystem, with a target population of around 350 buffalo, 130 elk, 200 mule deer, 175 white-tailed deer, 100 antelope, 40 bighorn sheep and 30 mountain goats.

About 125,000 visitors come every year to enjoy its delights. Many drive the one-way 19-mile road that climbs up and over the mountain among grazing buffalo and other wildlife.

No going back once committed!

The road to the top and along the ridge is delightful—high switch-backs but no heart-stopping drop-offs. It’s a two hour drive—maybe somewhat longer with summer traffic. And well-worth it!

The main herds are often found with their calves along the creek bottoms.

Here and there up high on the mountain can be seen a lone buffalo bull or two.

And at the summit of Red Sleep Mountain the view of the valley and the rugged Mission Range beyond is nothing short of spectacular!

History rightly gives a great deal of credit for saving the buffalo to the Duprees and Philips, Walking Coyotes, Pablo and Allard, McKay, Goodnights and Buffalo Jones.

We honor these five family groups with ‘boots on the ground’ who rescued buffalo calves and kept them alive, healthy and multiplying.

Without them, there’d be no American bison today.

Buffalo roundup in Badlands of North Dakota via helicopter. NPS.

Still, we also need to honor these visionary conservatists for their dedication and determination to provide the buffalo with safe places to live out their lives.

For their persistence in developing wildlife sanctuaries for buffalo throughout the United States, making them available for the enjoyment of people everywhere—William Hornaday, George Bird Grinnell and President Theodore Roosevelt are Buffalo Conservation heroes.

And yes, I believe Teddy Roosevelt well deserves his place on Mt. Rushmore as our greatest Conservation President!

Bully for him!

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog

Well written research!

I had no idea that Teddy Rosevelt was such a conservationist. An incredible man. He deserves his face carved in a mountain.

Oops Roosevelt.

Hi Carol

Yes! Thanks for writing.

I must confess that by the time I pulled TR’s accomplishments together, I too was amazed at all he had done for us, the American people! Roosevelt’s timing was just right, too, of course. Anyone trying to set aside such lands today risks taking it from someone else, so that can pose a problem—as some have discovered to their chagrin.

Here in North Dakota we are proud of TR. And we look forward to the building of the Theodore Roosevelt Library beginning this summer within the borders of his National Park—at the top of the hill where buffalo still roam!

We’ll let you know more as it progresses.

Best Wishes, Francie