Top Sales at Gold Trophy Bison Show and Sale

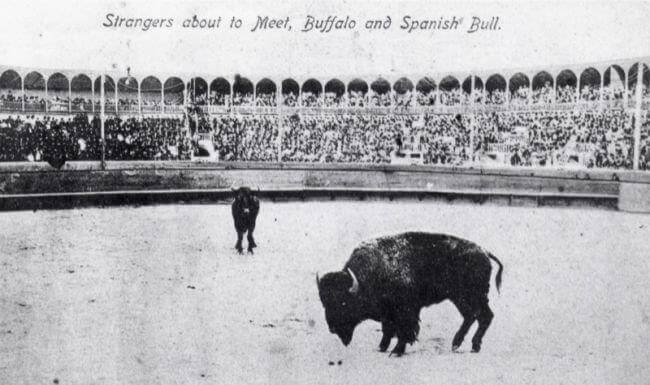

Westminster, CO (January 26, 2023) – Over 500 ranchers gathered last week for the National Bison Association Winter Conference, and brought with them about 100 head of live bison to the National Western Stock show to participate in the Gold Trophy Show and Sale.

The mission of the Gold Trophy Show and Sale is to create an environment where producers can compete to establish the value of their bison in the current marketplace.

Thank you to all of our consignors and buyers that made the 2023 Gold Trophy Show and Sale a huge success! Thanks too to our great volunteer handling team, the “Buffaleros”, as well as Karen Conley for organizing a great show and sale. Finally, thank you to our GTSS award sponsors, and Rocky Mountain Natural Meats for sponsoring the banquet dinner.

All of the bison growers bring with them a commitment to continue building the market for bison meat based upon the quality of the meat and a dedication to sustainable ranching practices.

John Graves, Yard Supervisor for the Gold Trophy Show and Sale, commented, “The GTSS animals were some of the highest quality we have had, making judging them quite a challenge.”

Wolverine Bison Company brought the Grand Champion Male. Buffalo Run Ranch had the Reserve Grand Champion Male. Snyder Land and Development brought the Grand and Reserve Grand Champion Females; and also received the high honors of Producer of the Year. Wrapping up the recognitions was Miller Bison, LLC, landing the Rookie of the Year award.

On Saturday, January 21st, at the National Western Stock Show, the award winning animals were sold by live animal. “Previous winning entries at the Gold Trophy Show and Sale have served as foundation seed stock for most of the top buffalo herds throughout the United States.

“We expect great things from these animals, and the prices reflected the quality charging through these pens today,” said Lydia Whitman, Program Manager with the National Bison Association.

The Gold Trophy Show and Sale is held annually at the National Western Stock Show by the National Bison Association and the Rocky Mountain Bison Association, which collectively represent nearly 2,000 members in 48 states and 10 foreign countries.

Information on the National Bison Association is available at www.bisoncentral.com.

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog