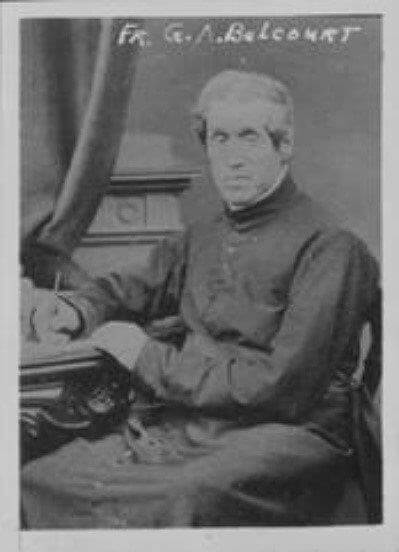

In 1845, Father G. A. Belcourt went on a bison hunt with the Métis (MEH tee or MEH tees) people of the parish where he had established a mission 13 years earlier. Soon after the hunt, Belcourt wrote to a friend in Quebec (Canada) and described the hunt in great detail. Following is his description of the hunt.

“The hunters gathered at Pembina where the 55 hunters assembled a train of 213 carts, 300 horses and 100 oxen. Their families, 309 people in all, went along, too.

Father George Antoine Belcourt was a French Canadian priest who established missions among the Chippewas and Métis of the Red River and Turtle Mountains. His letter of 1845 on the bison hunt describes the method of the hunt and the processing and preserving of the meat and other parts of the bison. Father Belcourt’s letter also tells how European American culture was beginning to have an impact on Métis culture. SHSND 0986-04.

“Carts carried a thousand pounds of gear including firewood, lodge poles for their tipis, drying frames and hide stretchers, as well as food. They were heading into the ‘boundless prairies’ of Dakota where they would have to bring everything they needed, including firewood.

“Their route took them south of the Turtle Mountains towards Devils Lake, the Sheyenne River, and west toward Dogden Butte (Maison du Chien).

“Scouts traveled ahead on horseback looking for good places to hunt and camp. The scouts rejoined the main group in the evening, bringing information on bison herds ahead.”

Soon, two young men returned to camp with fresh bison meat. Father Belcourt was offered the tongue, a delicacy, rather than the meat of the bulls which was more abundant, but likely to cause “mal de boeuf,” or indigestion.

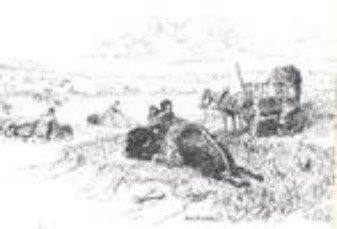

Metis hunters rode to the hunt with a loaded muzzle-loading gun and four more lead shot balls in their mouths. They re-loaded in the field by spitting the ball into the muzzle (front end) of the gun. Rapid re-loading meant that the hunters brought home more game and were able to protect themselves from charging bison bulls. Drawing by Vern Erickson, North Dakota History 38:3, page 340.

When they spotted a herd of bulls, Belcourt and a group of hunters approached to within 500 yards. They slowed their horses to a quiet walk so they could get near the animals without scaring them.

The bulls noticed the hunters and began to threaten them, stamping and tossing the earth with their horns. Other bulls watched the hunters and bellowed.

When they were close enough, a hunter gave the signal to ride their horses rapidly toward the herd. The bulls took off running “with surprising speed.”

Using guns, the hunters fired into the herd, killing some animals and wounding others. A half-hour later, the hunt on this herd was over. But a cloud of dust on the horizon signaled the presence of bison cows, and the hunters took off after them.”

Once the bison cow or bull had been killed, it was set up on its stomach and the hind legs stretched out behind. Drawing by Vern Erickson, North Dakota History 38:3, page 344.

Women then skinned the carcass and removed the meat, fat, bones and organs that were useful to them. The meat was dried for long-term storage. The fat was mixed with powdered dried meat and dried berries to make pemmican.

In that year of 1845, when Father Belcourt attended the hunt, Metis hunters brought home the meat and by-products of 1,776 bison cows.

The hunters were excited and their well-trained horses wanted to charge into the cow herd, but approaching the cows was the most dangerous part of the hunt.

The hunters had to ride through the bulls that were bunched near the cows. If a bull gored a hunter’s horse and knocked the rider to the ground, the hunter would be killed by the bull’s horns or feet.

The hunters carried muzzle-loading guns. They approached a herd with one shot prepared and carried 4 other balls of lead shot in their mouths.

They re-loaded their guns while riding their horses at great speed. They dropped the gunpowder into the muzzle and then spit a ball down the muzzle. A good hunter could load and shoot five times in the time it took to ride 100 yards.

On the first day, the hunters in Belcourt’s group killed 169 cows. In four days hunt, they killed and butchered 628 bison. By the end of the hunt, 1,776 cows had been killed.

Men and women worked together to butcher the carcass. After removing the hide, they took the hump (part of the back bone just below the neck) which was considered to have the best meat.

They also took the meat from the ribs and back bones, hips and shoulders. They removed the fat, the paunch or rumen (stomach), the kidneys, the bladder and the tongue.

The women cut the meat into strips about a quarter of an inch thick. These strips were hung on the drying frames for two or three days.

By then, the meat was so dry it could be rolled up and packed into large bundles.

Some of the less desirable pieces of dried meat were laid on a tanned hide and pounded into a powder. The meat powder was mixed with fat and poured into a rawhide bag called a taureaux (a French word for “bulls”). The mixture was called pemmican.

The Métis often added dried fruit into the mix. The resulting food was rich in nutrition and would keep almost indefinitely.

By the middle of October, the hunters were ready to pack for the return home.

The hunt resulted in 228 taureaux, 1,213 bales of dried meat, 166 sacks of fat (weighing 200 pounds each), and 556 bladders of marrow (12 pounds each).

Belcourt estimated the bison products to be worth £1700 ($218,179 today). The people had enough meat and pemmican for their winter food supply.

Father Belcourt concluded his letter with a commentary on the discipline of the hunt.

If a hunter started out alone, he might kill three cows and scare away the rest of the herd. He noted that in recent years, Métis hunts had lacked organization and leadership.

An organized, well-disciplined group of hunters could take 300 cows. Belcourt believed that religious leadership led to harmony and productivity on a bison hunt.

The Métis hunted bison in much the same way that their Chippewa relatives did, though they apparently lacked the tightly controlled organization that was necessary for a successful hunt.

Father Belcourt encouraged other priests to hunt with Métis of their parishes because, he believed, a priest could encourage the hunters to work well together.

Father Belcourt recorded an important part of Métis culture, and he also recorded the ways in which European American culture was bringing change to the people of the northern Great Plains.

Explorers and the Fur Trade

Fur traders entered the region that became North Dakota around 1800.

A few independent traders may have entered the region earlier, but Alexander Henry of Canada on the lower Red River (1799) and American Robert Dickson on Lake Traverse (1800) were the first to build trading posts that drew on the rich fur resources of eastern North Dakota.

The Hudson’s Bay Company and the North West Company competed with each other by building posts very close to one another.

They also tried to take business away from each other by offering better deals to their Indian trade partners.

Both companies engaged in over-trapping beavers to drive the other company out of the region. They succeeded in nearly destroying the beaver population of the region and in degrading the cultures of many Indian tribes.

Many smaller companies entered the fur trade, but most were eager to sell their business to a larger company after a year or two of tough competition.

In 1821, the beaver trade came to an end when European fashions in hats changed from felt made from beaver fur to silk.

The fur trade was both very good and very bad for American Indians who participated in the trade. The fur trade gave Indians steady and reliable access to manufactured goods, but the trade also forced them into dependency on European Americans and created an epidemic of alcoholism.

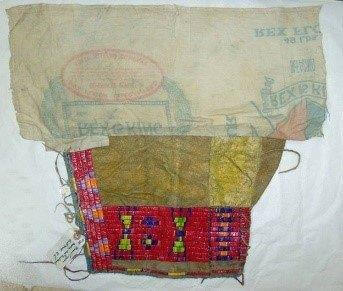

Indians who traded with European Americans received all kinds of manufactured goods in exchange for furs. Indians sometimes re-used the goods in ways that better suited them. These leggings were made by a Lakota woman, Anne Good Eagle. She constructed the leggings with a cotton cloth flour sack from the Royal Milling Company and leather. She then decorated them with dyed porcupine quills. The leggings would have been tied around a woman’s legs. Only the decorated leather would show below her skirt. SHSND Museum collections. 1986.234.222

There is no doubt that knives with steel blades, iron cooking kettles, guns, hoes with metal blades and other manufactured goods made life a lot easier for Indians. Though the trade items saved time for Indian women, much of that time was now given to cleaning and stretching beaver pelts or bison hides. There was a shift in the household economies of Indian families that, at first, seemed to produce greater security and efficiency.

American Indians often re-made trade goods into something they found useful.

For instance, manufactured pipe stems made of bone were intended to be used with corncob pipes. However, the Poncas used the pipe stems as beads.

The style spread to the tribes of the northern Great Plains and they became very popular for use in elaborately decorated breastplates. The pipe stems came to be known as hair-pipe beads.

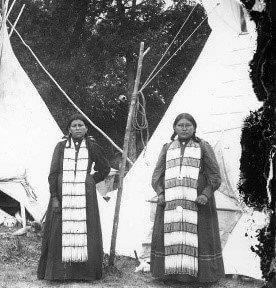

The young Dakota women in this picture are wearing breastplate necklaces made of bone hair pipe beads (light colored) and glass beads (dark colored). The hair pipe beads were originally designed to be pipe stems for corn cob pipes. Ponca Indians decided to use them as beads. The manufacturer, taking the new market into account, re-styled the hollow bone pieces as beads. The new use spread to the northern Plains where people of many tribes adopted the design. SHSND 0009-26.

Quill work. Traditional decorations like this horse brow band were made from porcupine quills. In the early 1800s, traders brought dyes to the northern Great Plains and women began to dye quills to make beautiful designs. SHSND Museum collections, 1882.

Colorful glass beads were a common item in the fur trade. Native women used beads to achieve a high level of artistic expression.

Beautiful designs stitched in colored beads graced their clothing, their moccasins, and ceremonial goods such as pipe stems, blankets and saddle bags.

Women still decorated objects with porcupine quills, now colored with dyes they received in trade, but increasingly more items were decorated with intricate beadwork designs.

Though traders might have thought that glass beads were a cheap item to exchange for beaver pelts, women applied their special design skills in beadwork.

Some women were able to trade their beading skills with other members of their tribe for food, horses or other things they needed.

This velvet vest was decorated with glass beads in a traditional Chippewa/Métis floral design. Glass beads were an important trade item. Indian women exchanged furs for glass beads and other manufactured goods. Glass beads were used to decorate clothing and other items. The most intricate designs were made for special occasions. SHSND Museum. Collections, 1987.84.1

Indian women were important agents in the fur trade. Men usually trapped beavers, but women scraped the flesh off the fresh hide, stretched it, and properly prepared the pelts for trade.

They often made the decisions about which company they would trade with. They also demanded the best rate of exchange.

They sometimes lost control of the trade when a trader, such as Alexander Henry, forced the trade to go in his direction.

During one visit to the Mandan villages, Henry fought with the women who owed their furs to the XY Company in payment for their debts. Henry finally won, but he had to force the women to give up the furs.

The women then had to acquire more furs (and work harder) to pay their debt to the XY traders.

Indian women were important agents in the fur trade. Native women scraped the flesh off the fresh hide, stretched it and properly prepared the pelts for trade. They often made the decisions about which company they would trade with. They also demanded the best rate of exchange.

Some Indian women chose to marry European American traders in the fashion of the country.

This generally means that these marriages were not recognized by law or religion. While many marriages brought loving couples together for the rest of their lives, other marriages were short-lived.

The children of mixed marriages in the Red River region formed a new culture called Métis. The mixed-blood children of marriages in other tribes usually grew up with their mother’s people.

Traders, especially those working for the North West Company, often used liquor to persuade Indians to trade. Sometimes, liquor was used to cheat Indians out of their furs. Liquor diminished the capacity of American Indians to make good business decisions.

Indians and trappers who drank too much got into fights; sometimes the violence led to murder. Though U.S. law (and the Hudson’s Bay Company) prohibited the transport of intoxicating liquors into Indian country, it was difficult to enforce this law.

If an Army officer found liquor on a fur trade boat, he would destroy all of the kegs, but there were not enough officers to patrol river traffic.

Many relationships between traders and their Indian partners were friendly and respectful.

Indian tribes and fur companies enjoyed mutual benefits from the fur trade. Indians obtained manufactured goods such as guns, knives, cloth and beads that made their lives easier. The traders got furs, food and a way of life many of them enjoyed.

However, competition among the tribes and among the fur companies created more conflict than peace. In addition, the fur trade led to the destruction of individuals and tribes even after the fur business ended.

Fur traders gathered information about Indian country that drew farmers, miners and railroads to the northern Plains.

The people who followed the fur traders were usually most interested in taking land from Indians. The Native Americans’ ability to resist was diminished by alcohol, disease and dependency on trade goods, as well as broken treaties with the US government.

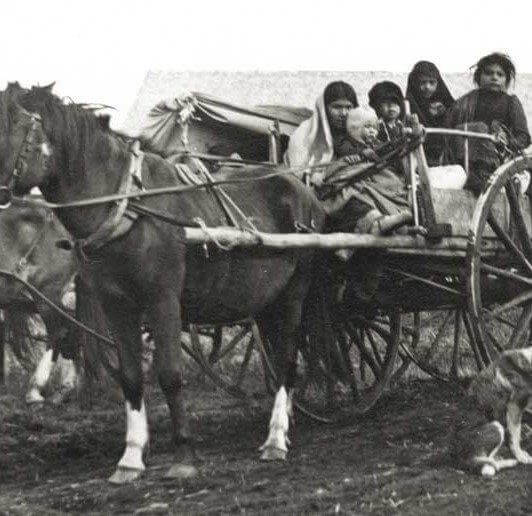

After successful buffalo hunting in the plains of Canada, Montana or Dakota Territory through the 1850s, long caravans of Metis often travelled on to St Paul or Winnipeg to trade buffalo products through the fur trade. These included hides, fresh meat, cured pemmican made of dried, pounded meat mixed with melted fat, and fine beadwork which were exchanged for such needs and desires as tools, guns, ammunition, housewares, cloth, blankets, beads and alcohol. By 1880 plains bison were nearly gone from Canada and Montana, as well as having disappeared from the southern plains by 1875. The last herds were killed in what is now North and South Dakota in traditional hunts on the Great Sioux Reservation by Lakota and Dakota Sioux.

The fur trade was a business that made profits for the owners and many of the traders. But it was also a cultural meeting ground where all of the participants were on equal footing. Everyone had something of value to trade.

However, in the long run, the fur trade was also destructive for the American Indian tribes of this region.

Many people forgot traditional skills for making things such as knives or hoes that they could now purchase with furs. Traders brought deadly diseases to Indian communities.

Violent conflict often broke out between tribes that participated in the fur trade. There was some good in the fur trade, but more often, the effects of the fur trade were not positive for American Indians.

______________________________________________________________________________

NEXT: WHAT’S AHEAD FOR THE BUFFALO?

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog

Hi

I Just read your story on Sir Donald. I did not know this story . . . Very interesting.

I grew up in the town of Stony Mountain and have read several stories of Col Bedson’s wild game farm and his Bison herd at Stony Mountain and have always found Bison history very interesting. I have a connection to Lord Strathcona’s Bison Herd that you may find interesting.

Now I have proof my Great Grandfather had a connection with some of the last wild Bison in Canada. Very Proud of him even though I never knew him.

I have heard the story of a picture of my Great Grandfather—Alexander Green—that was lost or stolen when my grandparents moved in the mid 1960’s. My Grandmother inherited the picture after her father died in 1948 and it hung in their home until they moved.

My Mother told me the picture was very old and said it was even published in a local newspaper. With the original long gone I have tried several times to find it on the internet. Finally just today I found the story but as a remembrance of 50 years earlier. Now I need to find if there was an original story and photo in 1897 or there abouts? This story is in The Winnipeg Tribune 1947-11-11. This paper no longer exists but the U of Manitoba have their records.

I will need to figure out what the connection is between Bedson’s herd in the corral and Lord Strathcona’s herd and the whole time frame. Would Sir Donald be in this Photo ?

Dale Baker

Balmoral MB, Canada