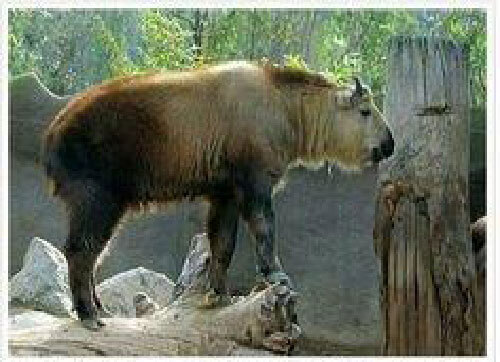

The cattalo herd at the Canadian Experiment Farm, Manyberries, Alberta, 1960. Photo by JH Gano.

Have you been thinking of crossbreeding some of your bison with beef cattle?

That has sounded like a good idea to lots of honest men and women for more than a century. If we can bring about in one animal: the best of both buffalo and cattle—that would be great, wouldn’t it?

How about having that sound intelligence and hardiness of American bison for every storm that comes along—evolved and adapted through thousands of years—to live in the far north?

And then mix in the abundance of great beef—not just what the slim-hipped buffalo provides, but real abundance in length and breadth of that tasty, tender loin and hip: mmmm.

Your beefalo—or catalo—or whatever you choose to call them—would certainly retain the best traits of both species, wouldn’t they?

Every few years it seems like some promoter is trying to sell that idea. Sounds like a good one, Right? Have you ever been tempted?

Sure, you dreamer! But wait a minute. Are you sure you’re getting the full and honest truth from that promoter? Maybe not.

There’s a long history here, well over 100 years—and for all that time some people have not been willing to tell us the facts.

Oh yes, veterinarians know the truth. Canadian researchers know it, too.

But they’re too polite—or discreet—to give us the facts. Or they’re too busy to get involved in something that doesn’t smell quite right.

So before you involve yourself—if you’re an honest person, listen first to the research I’ve uncovered.

It’s not pretty.

We all hear how much buffalo ranchers love their animals. You do too, don’t you?

Bison and cattle hybrids are also known as cattalo or beefalo. Bison mixed with Herefords often retain the white face like this cow from Buffalo National Park near Wainwright, Alberta. Photo Peel’s Prairie Provinces, U of Alberta Libraries

‘The Violent Cross’

The obvious, simplest way to get started in crossbreeding is to use Bison Bull semen and artificialy inseminate a dozen of your beautiful Angus heifers with it. The calves might even be born naturally hornless. Nice, huh?

But wait.

A Bison bull cross with a domestic cow. What could go wrong?

Well, what everyone interested in crossbreeding needd to know is that Canadian reseachers call this “the Violent Cross.”

So what’s the worst?

Would it be if you killed off a good share of those Angus heifers? Or that most calves were aborted or born dead? And any male calves were rendered infertile?

It’s hard to uncover statistics and facts from the research we get—even from Canada. Most generally the experts are evasive. Over and over they report simply,, “it didn’t work.”

They don’t say why: they don’t give figures and statistics, as researchers are supposed to do.

Even if you weren’t told why, but knew that the experiment meant killing a good share of your nice heifers would you do it? I don’t think so.

How about killing as many as 30 percent of your females and 77 percent of their calves?

All that could happen. It seems to have happened again and again in Canada over 50 years. Apparently the two species are genetically incompatable.

The bison hybrid cross was allotted only a few sentences, a couple of paragraphs in the Manyberries’ report: “One Hundred Harvests, 1886 to 1986,” published by the Research Branch, Agriculture Canada in 1986.

Seemingly, it’s a brush-off. Not much there. Just forget it happened.

It was terse and to the point. Plainly the entire 50-year experiment was unsuccessful: The 100-year report admitted the consequences bluntly: “The bison crosses with domestic cows resulted in 77 percent calf mortality and males of this and the reciprocal cross were invariably sterile.”

Also no advantage in growth or carcass performance. The end.

This was the most specific I was able to find in most any report. And It took a lot of digging.

It didn’t mention why—or the deaths of mother cows. But others did.

A second official report “Lost Tracks: Natl Buffalo Park, 1909-1939,” written by Jennifer Brower was more specific.

She says, “The bison male and domestic female cross resulted in a high number of calves aborted or stillborn. The cause of these deaths was attributed to an excessive amount of incompatible amniotic fluid surrounding the fetus.

“It was called the violent cross because the cows often succumbed as well.”

She does not explain what she meant by ‘often.’ Perhaps half—or more, or less?

“Because of the high incidence of mortality among the cows, they discontinued the bison sire and domestic cow cross in favor of the domestic sire and bison cow cross, with which the Dominion government had more success.”

Not a total success, however, as many calves still died: she was silent on the fate of cows.

The conformation of surviving adult hybrids was far from optimal. Each one had an odd look of its own.

Finally in 1965—after nearly 50 years—the Canadians threw in the towel: they butchered all the hybrids.

However the reason they came up with is unconvincing.

They reported: the hybrid wasn’t needed in the far north: ranchers said Hereford and Angus cows were doing just fine.

It’s disappointing to get an excuse like that instead of a real answer.

If at that point these good Canadian researchers would have given us the awful reality clearly: pointing out consequences in percentage of dead cows and aborted calves and what killed them, maybe this madness would have ended abruptly.

The two species are simply incompatible. Why not make this clear?

But they didn’t.

They continued to circle the wagons and avoid admitting the worst: while cows and calves may continue to die.

Canadian Experiment Begins

The violent cross: daughter of domestic cow and Bison bull. In one report 77% of calves died or were aborted before birth. Often the mother died too.

In 1916 the Canadian Parks Branch and Deptartment of Agriculture initiated the crossbreeding experiment inside the borders of Buffalo National Park near Wainwright, Alberta. The Park already held a big herd of Plains buffalo purchased from Michel Pablo of Montana.

Later the crossbreeding part of the buffalo program was moved to Manyberries, which was a government cattle experiment station.

It sounded like such a good idea.

The purpose of the program—which ultimately lasted over 50 years—was to create a hardier breed of range cattle to overcome the blizzards of the far north in northwest Canada.

In addition to their natural hardiness, the hybrids were expected to produce a larger quantity of high quality beef than the slim hipped buffalo could provide.

One glowing news article Popular Science Monthly imagined this magical herd of the future with high hopes: “A valuable new breed of hardy cattle called ‘cattalo’ that will range wild in the north.

“Feeding themselves, great herds of cattaloes, it is expected, will increase at no expense, as long as the northern plains remain unsettled. It is too cold in the north for ordinary domestic cattle, unless shelters are provided for them and they are fed artificially.

“Promises to become a reliable source of meat in northern Canada where domestic cattle, because of severe climate conditions, have found it hard to exist.

“Possessing some of the characteristics of both cow and buffalo, the new type of animal has the meat qualities of beef cattle, and like its buffalo forbearers is hardy enough to find its own food even in the coldest weather.

“The latter quality is highly desirable for the far north. By hunting their own food, the cattalo save settlers the labor of feeding them hay all winter. They can be left out to graze without fear of their becoming lost in the heavy snows.”

A ready-made partly hybrid herd was at hand from Mossom Boyd, a wealthy man from Bobcaygeon, Ontario, who began his cattalo experiments in 1894. He supposedly crossed a purebred bison bull he brought from California with several different breeds of domestic cows.

When Boyd died in 1815, his cattalo herd was sold to the Canadian government and moved to Buffalo National Park.

it was a program beset by difficulties from the beginning.

Not always did the various Directors of the Buffalo Program approve of the hybrid experiments. Often they were short on funding and the focus on hybrids faltered correspondingly.

However, of all the experiments up to this point, Boyd’s three-stage process appears to have been the most methodological. He identified the offspring from each stage by a different label.

- The first stage involved crossing bison with domestic cattle. The offspring he called hybrid.

- The second stage was to cross the hybrid product from the first stage with a purebred animal of either bison or domestic cattle descent. This was called by the percent of bison in the cross—as a ¼ or ¾ buffalo.

- The final stage, to be reached by 1913, involved breeding two animals, both of mixed parentage, with each other. Only the offspring of this stage would be called cattalo.

But after 10 years—by 1925—none of the animals from the Boyd herd had produced any offspring. Despite different combinations of sires and females used and each subject to regular examination by veterinarians.

Thus, the researchers were forced to start again from scratch and encountered all the obstacles with the first cross they had hoped to avoid.

Hardy Yakkalos

A yakkalo is a cross beween a bull yak and an American bison cow. Not occurring in the wild, they were created by Canadian scientists in the 1920s conducting experiments in hybridization.

For a time, the park at Wainwright also bred bison with yaks, producing ‘yakkalo.’

They reported, “Experiments now are being made in crossing the buffalo with the yak, a draft animal from Asia. Yaks are splendid range animals capable of withstanding the effects of long, rigorous winters in the open and at the same time they are domesticated.

“Their meat, except that it is finer grained, is almost identical with beef. The natives of Asia have crossed the yak with domestic cattle successfully for many years. Now, this yak hybrid is being crossed in Canada with the bison.

“The yak acts as an intermediate stage in the process of developing cattalo.

In the 1920s it was believed that bison were at the primitive end of an evolutionary continuum that eventually led to the ‘perfection’ of European domestic cattle. Yaks were thought to be at a halfway point between bison and domestic cattle.

The last word on the Yak hyybrids: “very few of the yakkalo calves survived and the program was discontinued in 1928.”

This was not the first time crossbreeding bison had been attempted.

In the US both Charles Goodnight of Texas and Buffalo Jones of Kansas had tried to crossbreed buffalo with domestic cattle. As had others before them.

Both claimed far more success than they could show.

Goodnight praised his herd lovingly: “The cattaloes are a decided success. They will carry their young and make beef at any season of the year. They do well in the extreme south or far north.

“I have been able to produce in the breed the extra rib of the buffalo, making 14 on each side, while ordinary cattle have only 13 ribs on each side.

“They make a larger and hardier animal, require less feed and longer lived, and will cut a greater percent of net meat than any breed of cattle.

“I believe it will only be a matter of time until they will be used on all the western ranges.”

Buffalo Jones boasted of his cattalo—to everyone who would listen. In his mind they brought together the very best qualities of both species: bison and cattle. Although some suggested the cross brought out the worst of both.

In reporting on Jones, Larry Barsness explains the worst in his book “Heads, Hides and Horns:”

“In 1877—typically slam-bang ways—he turned young buffalo bulls in with his Galloway cows, hoping for a hybrid calf crop: a wild hope, for these were scarcely bulls, they were the two-year-olds and yearlings he’d captured as calves on the Staked Plains in 1886.

“No calves resulted. The next year 1888 he reported 80 or 90 pregnant cows–but only produced 2 live calves. Worse, 30 of the cows died giving birth or before. But he cruelly kept on experimenting.”

That’s about 33% of mother cows.

Barsness summed it up, “Too many cows died abirthing, too many cows aborted bull calves, too many bull calves died, too many bull calves proved sterile’”

“When they continued to die, he went on breeding.

“Charles Allard gave up trying to raise catalo on Flathead Lake Wild Horse Island, because he lost too many cows.

“About the same time in New Jersey, Rutherford Stuyvesant gave it up when 19 of his Galloway cows died calving.

“P.E. McKilip in Kansas had quit after 10 years, for the same reason.”

Director Harkin Quashed Private Efforts

From the time Canada first acquired bison for Rocky Mountain Park in 1897 private ranchers were requesting bison for crossbreeding.

But park officials refused to supply or sell them, saying ordinary citizens would not have the technical information to do it right.

The cattalo experiments became their excuse for refusal, charges Brower in her official report.

It was true the Dept of Agriculture had the necessary facilities, equipment and staff.

Harkin, the director, held firm. But of course he knew more than he was letting on. Just like researchers and veterinarians: he knew death losses in hybrid breeding were severe. The species were incompatable.

Likely he didn’t want the awful results publicized because that might jeopardize the government experiments.

At first the researchers noted, “Angus, Shorthorn and Hereford cows were used in the first mating with the buffaloes.”

But after sizeable disasters they switched to the opposite cross: mating a domestic bull with buffalo cows.

“This cross works better than the other way,” they explained briefly.

But in 1951, the manager at the Manyberries station wrote that the low fertility persisted into the next generations even when the bison blood was reduced to a low percentage.

“Only a few of the male ‘cattalos’ were fertile. Generally, male domestic bulls were crossed with buffalo cows, producing offspring of which only the females were fertile.”

Not much was revealed in the rare reports written by the researchers. Some mentioned through the years that the greatest difficulty was infertility.

Really?

When 77% of calves abort or are born dead—as was cautiously revealed at last—and maybe one third of mother cows die from being bred to a buffalo bull: it’s more than difficult. it’s devastating!

Of course in Canada some researchers held high hopes for surviving calves. They had a mixed herd to deal with however they wished. Maybe they could ignore the swamp and celebrate small victories.

Maybe the fact that nearly all male hybrid calves were infertile—and others died—just added one more wrinkle to the experiments.

Most often, reports simply noted a study was not successful: without explanation.

Barsness suggests the cause of so many deaths in birthing was proved by the Canadian Government as “an abnormal secretion of amniotic fluid.” Or was it that the fluids of domestic cows was not compatible with semen from a buffalo?

Why couldn’t the Canadian researchers have simply told us this?

Instead, when they stopped the government experiments and butchered all the hybrids—cattalo, beefalo and however they wanted to label or spell them–they came up with one more flimsy excuse: after all those 50 years “a new breed of cattle was not needed.”

Ranchers didn’t need them: Hereford and Angus breeds were tough enough for the northern most winters.

The underfunded hybrid experiments were a problem some directors did not want to deal with. They didn’t like having to mix the 2 purposes at Manyberries station: the original purpose of research with cattle—and then adding the problems of hybrids.

When Bud Cotton was early director of the experiment station at Wainwright, he reported that in order to obtain a true breed, hybrids must breed true, and he said their hybrids did not breed true. Crossing hybrids instead resulted in a wide variation of conformation type and also a loss of vigor.

In other words, so far the crossbreds had become random creatures; how could a rancher build a nice-looking herd with the ragtag ungainly creatures they saw in their hybrid herds?

King—one of the most famous cattalo animals. He was a rare male hybrid from a bison bull and domestic cow cross. Because of the high death rate among cows, this cross was discontinued in favor of crossing a domestic bull with bison cow. Photo by JH Gano.

Cattalo Thrive on Winter Forage

Meanwhile the researchers gamely threw the newcomers in with beef cattle experiments.

Cattalo calves were all thin after the trip from Wainwright in the fall of 1949 and most of the calves of less than 1/4th bison breeding required special care and feeding in sheltered pens during the severely cold period.

Cattalo calves of ¼ Bison and ¾ domestic cattle breeding demonstrated outstanding cold tolerance and survival ability on the range during their first winter at Manyberries.

They were able to withstand the cold weather without access to sheltered pens, as did cattalo with higher percentages of bison genetics.

The breeding cows at the Manyberries Station were wintered on native rangeland with a minimum of supplemental feed. A deep coulee known as Lost River crosses the field diagonally, providing shelter from the wind.

During the winter of 1951-52, a daily record was kept of the number of cows of each breed that were found grazing on upland prairie over a 79 day period.

Number of days when some animals grazed on upland (out of 79 days):

Shorthorn 25

Angus 26

Hereford 34

¼ Bison Cattalo 41

½ Bison Cattalo 50

Average percent of animals grazing on upland when some grazed:

Shorthorn 42.1%

Hereford 49.5%

Angus 71.5%

1/4 Bison Cattalo 61.1%

1/2 Bison Cattalo 96.2%

Feedlot Research

Many of the Canadian experiments over the years involved feeding yearlings: for example they compared weight gain of hybrids with calves of various breeds in 6 month feeding tests.

Random findings:

- Cattalo cows were superior to range Herefords in ability to graze on winter range in cold weather.

- Cattalo calves were lighter at birth and made greater gains from birth to weaning.

- Cattalo made significantly greater feedlot gains than bison and lower gains than Herefords in a couple of experiments

- Hereford calves made greater feedlot gains and had higher carcass grades.

- There was a significant reduction in carcass grade; a reduction in proportion of carcass weight in the hind quarters; and an increase in dressing percentage as the proportion of bison breeding increased.

The researchers noted that cattalo had excellent feet and were long-lived. Also it would be a good thing to retain the buffalo cow’s small, frost-protected udder.

Then suddenly at the end of one report: this project has been “discontinued because of fertility and temperament problems.”

Let The Buffalo be Buffalo

The final report of 100 years of hybrid experiments summed it all up briefly: still no good reason for failure except infertility—and that indirectly:

“The bison crosses with domestic cows resulted in 77 percent calf mortality and males of this and the reciprocal cross were invariably sterile: no advantage.

“Functional males carrying more than 1/8th bison never were observed.

“Subsequent studies indicated that, compared with Herefords, the cattalo had no advantage in growth or carcass performance.

“The work was discontinued in 1965.”

The good Canadian researchers were undoubtedly wise to end it all: pardon me, but it took long enough.

Today crossbreeding is generally discouraged. It violates the Code of Ethics of both the National Bison Association and the Intertribal Buffalo Council.

There’s good reason—even if few people are willing to say it aloud: yes, it kills mothers and babies.

Most bison breeders today are dedicated to protecting the integrity of the species.

They are proud to maintain historic buffalo traits that produce nutritious meat, help buffalo survive harsh weather and require minimum herd care.

This philosophy is often expressed as: “Let the buffalo be buffalo!”

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog