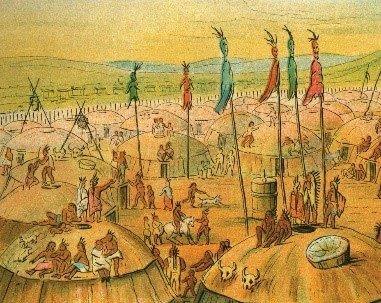

Birds-eye view of a Mandan village. Painting, Photo credit SHSND 970.1C289NL

Though the Mandans, Hidatsas and Arikaras grew enormous quantities of corn, beans, squash, and sunflowers, their agricultural practices were very different from the ones farmers use today.

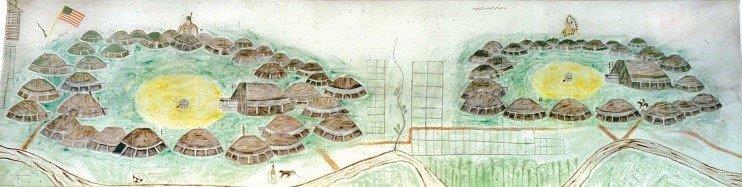

On-A-Slant village was built about 400 years ago near what is now Mandan, where the Heart runs into the Missouri River.

In 1915, a Hidatsa woman named Maxidiwiac (Mah HEE dee WEE ah), described to the anthropologist Gilbert Wilson her methods of growing corn.

She used traditional methods learned from her mother and generations of women before her.

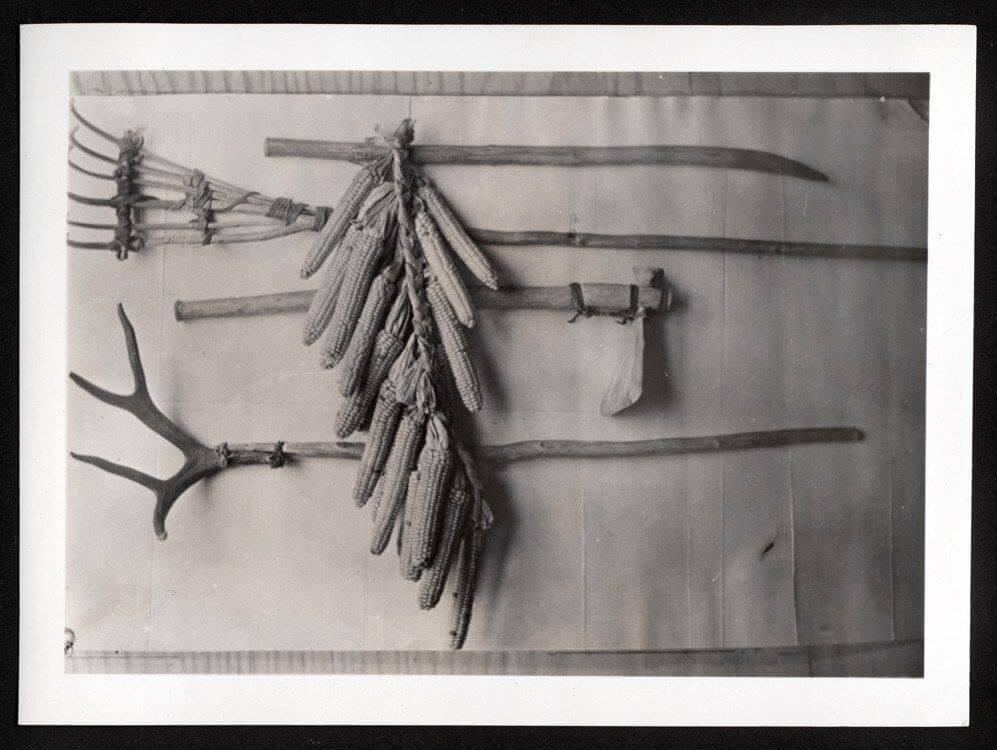

Image 1: This display of original gardening tools used by the women of the three tribes shows, from top down, a digging stick, a wooden rake, a hoe made with the scapula (shoulder blade) of a bison, and a rake made with a deer’s antler. In the middle is a braid of dried corn. Photo credit SHSND 0075-0386.

Maxidiwiac was known as Waheenee (Buffalo Bird Woman) when she was a young girl. At the age of 12, she began to assist her mothers in the garden. (Hidatsa children call their birth mother and her sisters “Mother.”)

Her first job was to sit on the watchers’ stage, a platform where little girls spent the day chasing crows and little boys away from the corn.

When she grew to be a mature woman, Maxidiwiac had her own garden. She was responsible for planting, protecting, hoeing and harvesting.

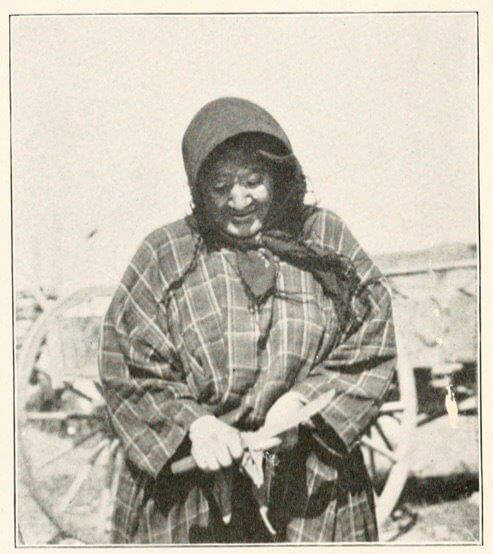

As an older woman, Maxidiwiac in her garden demonstrates corn drying and storage.

Her tools were made of iron and wood, but some women still used the traditional tools made of wood handles attached to antlers for rakes or wood handles attached to bison scapulas for hoes (image 1). The ground was prepared for seeding by digging with a sharply pointed stick.

Tools were made and used by Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara women for centuries, but when European American traders began to trade with these tribes, they brought hoes and rakes made with iron.

Many women kept the old tools because they could make them from local materials and did not have to depend on traders for their tools.

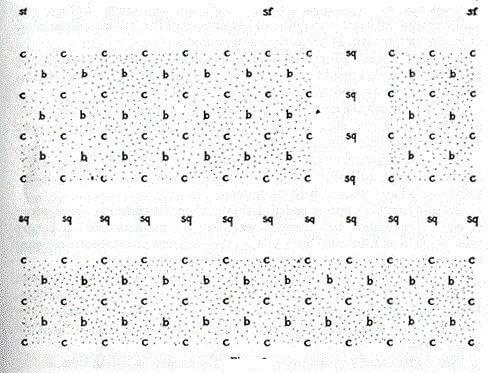

Image 2: The plan for Maxidiwiac’s garden shows rows of corn (c) alternating with rows of beans (b). Between the corn/bean patches are rows of squash (sq). Sunflowers (sf) were planted around the edges. The corn was planted about 12 feet from the garden fence so that stray horses could not reach the corn by leaning over the fence.

The women gardened on river bottom land. Upland ground (where summer homes were built) was too hard and dry, but the river bottoms were soft and moist.

When the leaves emerged on the gooseberry plants, the women started to plant corn. This was in May; planting was not completed until June.

The gardens included sunflowers, beans, squash and tobacco in addition to corn.

The seeds were planted so that each plant could take advantage of the qualities of the other. Beans were planted near corn (image 2). Several varieties of squash were planted in the wide spaces between sections where different varieties of corn were planted. The broad leaves of squash shaded out the weeds.

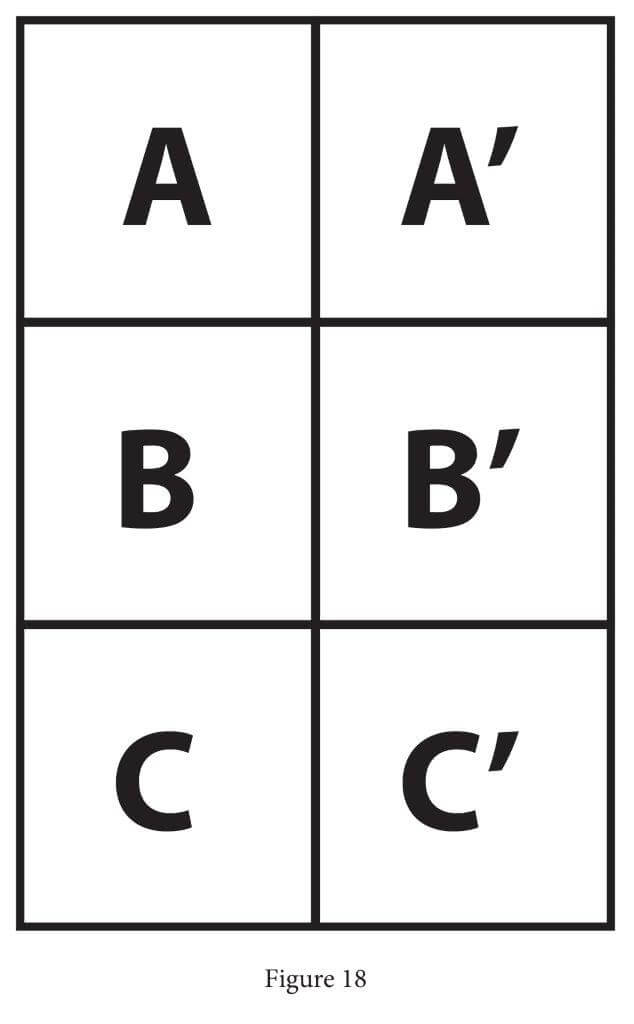

Image 3: Gardeners tried to avoid cross-pollination of their corn plants so they could maintain the genetic purity of the corn varieties. This illustration shows that one woman would plant the same variety of corn (A) next to her neighbor’s corn (A’). B and B’ were another variety of corn. Through cooperation and planning each woman could protect her seed corn for the following year.

First, Maxidiwiac, Buffalo Bird Woman, stirred up the dirt of last year’s corn hill with her hoe. She smoothed the soil with her fingers and placed six to eight dried corn kernels from the previous year’s crop in each hole. She patted dirt over the seeds with her fingers and moved on to the next hill which was about four feet away.

Each morning, Maxidiwiac planted several rows, each 90 feet long. Other women may have planted more or less corn according to the size of their families.

If a woman was ill and could not plant, members of her social group would plant for her. If they worked together, they could complete the planting in one morning.

Maxidiwiac’s garden was about three and a-half acres in size. It was divided into sections in order to keep different varieties of corn from cross-pollinating one another (image 2).

As the corn grew, the women hoed daily to keep the weeds from taking over the garden. They made scarecrows from wood frames and old blankets to keep the crows from stealing the young corn.

In early August, Maxidiwiac looked for signs that her corn was ripe.

“The blossoms on the top of the stalk were turned brown, the silk on the end of the ear was dry, and the husks on the ear were of a dark green color.”

This was “green corn” which was boiled and eaten fresh. Green corn was considered a great treat. Later in the summer, other varieties of corn were harvested and dried on the cob or as kernels. The dried corn was saved for the family’s winter use and for trade (image 6).

Image 4: In this Hidatsa woman’s garden, beans were planted between rows of corn. Each variety of corn was planted in a patch that was separated from other varieties. Squash was planted between corn patches. A typical garden was about 3 to 5 acres in size. SHSND 0086-0307.

Seed corn was specially selected and set aside. Maxidiwiac “chose only good, full, plump ears” without any sign of disease.

She put away enough seed corn to last for two years, so that if the crop failed in the next year, she still had seed for the following year.

Maxidiwiac raised nine varieties of corn. Each type had a different use: some were better for eating fresh, others better for drying. Some corn was ground to make flour.

To maintain the purity of their corn genetics, the women kept each variety separate.

Maxidiwiac usually coordinated her planting with the woman who had the neighboring garden so that their gardens would not cross-pollinate. (See Image 3.)

Corn was an important food for the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara, and it also had spiritual quality. The people of the villages performed certain ceremonies to ensure that they would always have a good crop of corn.

Corn agriculture gave the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara a secure and reliable source of nutrition. In addition, the tribes were able to trade their surplus corn for other goods and in that way, they became wealthy.

Mothers taught their daughters how to raise corn and other crops. Women of the tribes accumulated information on methods of raising corn and maintaining the qualities of each variety.

It was women’s work, agricultural skills and knowledge that brought economic and social advantages to the tribes.

These women were braiding corn for drying. Buffalo Bird Woman usually made 100 braids of dried corn for winter storage. The braids could be hung in the earthlodge. SHSND 0086-0277.

Yellow Nose sits with her husband Bear on the Water in front of their Mandan home. She uses a mortar to pound dried corn into flour. Behind them is a pile of braided dried corn. SHSND A0126.

Section 3: Mandan and Hidatsa Horses

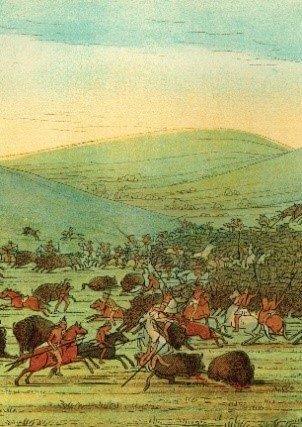

The Mandan and Hidatsa acquired horses at about the same time as the Lakotas did, around the middle of the 1700s (in the 18th century).

Like the Lakota, Mandan and Hidatsa made a place for horses in their culture. They found that horses were very helpful in hunting bison and allowed them to travel much farther in search of the wild herds. Work became easier.

Horses did not change traditional village organization, but the acquisition of horses became an important “calendar” date. Events were identified as having happened before or after the tribes acquired horses.

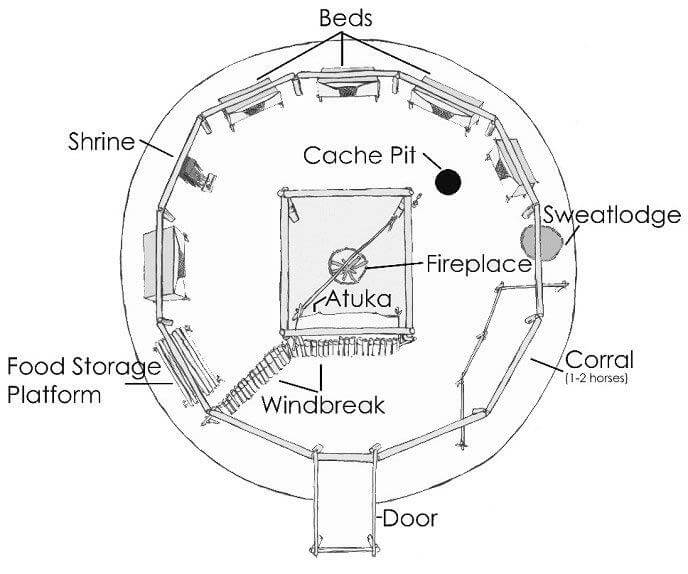

Image 5: Earthlodge. Mandan and Hidatsa lived in roomy, comfortable earthlodges. To protect their horses from raids, the men often brought their best hunting or war horses into the lodge. Women brought corn husks and stalks to feed them. The plan of this typical earthlodge, shows the small corral on the right side for horses, near the lodge door. SHSND.

Horses were so important that they soon became integrated into many village traditions.

Both men and women owned horses. However, women owned mares and foals while men owned stallions and geldings. Women had horses for riding and horses for carrying burdens.

Mandan men acquired horses through raiding the herds of their enemies, but women acquired horses through certain family or clan relationships.

A young man paid respect to a woman of his family or clan by offering her horses. When a young man went on his first horse raiding expedition, he gave the horses he captured to his eldest sister. This was a way of honoring her.

If his sister was already married, she extended that honor by offering the new horse to her husband. If a young man struck his enemy while capturing horses, he would be given a new name by an elderly woman of his father’s clan. The young man paid the woman for this honor by giving her horses.

Horses made everything easier, from hunting buffalo to moving camp and hauling garden produce for storage from the Missiouri River lowlands up the hill to Mandan and Hidatsa earthlodges.

Horses were also important in arranging a marriage between young people.

The Mandans had several systems for arranging a marriage. In one form of marriage, a young man’s family found a young woman who would make a suitable wife for their son.

The man’s parents offered horses to the parents of the young woman. If the woman’s parents agreed that the young man would make a good husband for their daughter, they accepted the horses.

The bride’s parents then gave the horses to their sons, who honored their sister (the bride) by giving the horses to her. The bride offered the horses to the father of the young man she was going to marry. In this exchange, both families acknowledged their approval of the marriage and showed respect to each family.

Mandans and Hidatsas considered horses to be a sign of wealth. The trading of horses between the families symbolized to the bride’s family that the young man came from a respectable family with enough resources to provide well for the young woman and her future children.

The young man’s family offered enough horses (wealth) to demonstrate to the bride’s family that they held the young woman in high esteem.

Horses did not come to the Mandans and Hidatsas without some notable problems.

Horses like to eat young plants and corn at any stage of growth, so they had to be kept out of the large gardens where the women of both tribes raised corn, squash, beans and sunflowers.

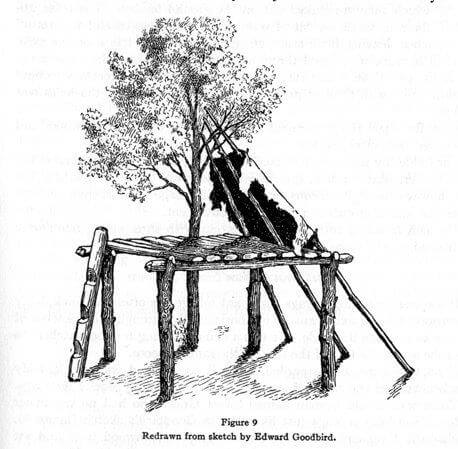

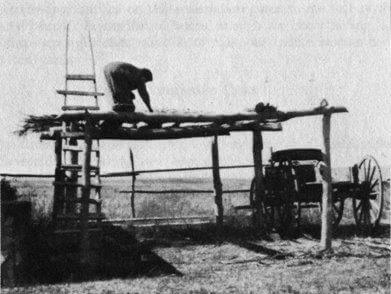

Women usually erected platforms in the garden where they or their children watched over the growing crops and kept horses and other garden-raiding animals away. The platforms were also used for drying corn and squash and other plants after harvest.

Horses also needed feed in the winter, especially when the snow was too deep for them to reach the grass. Usually cottonwood or willow bark served as winter feed, but finding and carrying winter feed to the horses added extra labor to ordinary winter chores.

Buffalo Bird Woman and other Hidatsa and Mandan women fed corn stalks to their horses, but also had to prevent horses from destroying the gardens.

Maxidiwiac (1839-1932) explained gardening to Gilbert Wilson around 1915, when she was a very old woman. In the following paragraphs, taken from Gilbert Wilson’s ‘Buffalo Bird Woman’s Garden,’ Maxidiwiac describes how Hidatsa gardeners adapted their gardening methods to horses.

Acquiring Horses, by Buffalo Bird Woman

“At the very first it is true, we did not own ponies; but we soon got them. I think my tribe obtained ponies from the western tribes. In my own youth we Hidatsas got many of our horses from western tribes, especially from the Crows. . .

“In the early part of the harvest season, when we plucked green corn to boil, we gathered the ears first.

“Afterwards we gathered the green stalks from which the ears had been stripped. These stalks with the leaves on them we fed to our horses, either outside the lodge, or inside, in the corral.

“We commonly husked our corn, as I have said, out in the fields, piling up the husks in a heap. After the corn was all in, we drove our horses to the field to eat both the standing fodder and the husks that lay heaped near the husking place.

“Horses readily ate corn fodder, and by the time spring came again, there was little left in the field. Not only were the husks devoured, but most of the standing stalks were eaten off nearly or quite to the ground.

“Okĕi’jpita. . . is a small ear that sometimes appears at the top, on the tassel of the plant. Okĕi’jpita ears, if large enough, we gathered and put in with the rest of the harvest. But smaller ears of this kind, hardly worth threshing, we gathered and fed to our horses.

“Sometimes, if the harvesters were in haste, these ears were left in the field on the stalk; a pony was then led into the field to crop the ears.”

Protecting the Gardens from Horses

Bridle band. This brow band fit across the horse’s face above the eyes. It symbolized how much the owner treasured his or her horse. The brow band is made of leather decorated with dyed porcupine quills, tinkling cones and dyed feathers. This band is in the collections of the State Historical Society of North Dakota. SHSND Museum, Hoffman Collection.

“Horses did not trouble us much, as we did not permit them to graze near our garden lands. They were pastured on the prairie,” said Maxidiwiac.

“We always had fences around our fields as long ago as I know anything about and I have heard that our tribe had such fences in the villages they built at the mouth of the Knife River, to protect their fields there from their horses.

“Such, I have heard, has been our Indian custom since the world began.

“I think our fences stood 12 or 15 feet away from the cultivated ground, as I pace it here on the ground. I know no reason why they were run thus, except as I have said, to keep the horses from nibbling the corn.

“You see, 15 feet is quite a little distance; and the fence could have stood closer to the cultivated ground and still been far enough away to keep the horses from nibbling the crops. All I know is that it was a custom of my tribe and I always followed this custom if I had a fence to build.

“Pacing it off here, on the ground, the length of the stage was, I think, about so long–30 feet. Its width was about thus–12 feet.”

Image 6: Stage platforms were built for watchers to protect the gardens from horses, birds and boys as crops began to ripen. This sketch shows ladder at left, buffalo calf skin folded fur out made seat for watcher, folded to make a cushion for sitting on the uneven pole floor. A tree may be incorporated for more shade. Sketch from Bird Woman’s Book.

Three poles supported a second calf skin used as a shield against the sun. Image 6 shows three moveable poles that could be shifted to provide shade through the day.

“From the ground to the top of the stage floor was a little higher than a woman can reach with her hand, or about 6 feet, 6 inches. There were horses in the village and the stage floor must be high enough so that horses could not reach the corn.

The woman above is placing slices of squash she has threaded onto long sticks for drying. Corn and other foods as well were laid on the platforms to dry and preserve for winter eating.

“The season for watching the fields began early in August when green corn began to come in; for this was the time when the ripening ears were apt to be stolen by horses, or birds, or boys.”

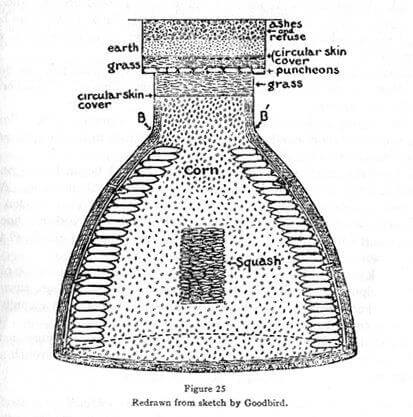

Dried foods were then placed in cache pits for storage within and just outside the earthlodges which were built on plateaus higher up above the river.

Image 7: Maxidiwiac explained that she dug the cache pit like a jug—deep enough so she could just see out the top and as large as a bullboat at the bottom. Then she lined it with grass and filled it with dry corn and vegetables.

“The pit was dug into the ground in the shape of a jug. The entrance was about 2 feet across and the size of a bullboat at the bottom. It took two or three days to dig.”

The big ones had a ladder, the smaller ones when standing on the floor, her eyes just cleared the top of the ground above. The cache was lined with a special bluish grass that did not mold.

They covered the cache and heaped earth in the pit until it was level with the ground.

“Lastly, we raked ashes and refuse dirt over the spot, to hide it from any enemy that might come prowling around in the winter, when the village was deserted.”

Smaller caches may be buried inside the lodge itself. “A cache pit lasted for a long time, used year after year,” she said.

Horses for Carrying Burdens

“In the fall, when we went to our winter lodges, corn, squash, beans and whatever else was needed, we loaded on our horses and took with us. As soon as we came to our winter lodge we made ready a cache pit at once and stored these things away.

“We Hidatsas did not like to have the dung of animals in our fields. The horses we turned into our gardens in the fall dropped dung and where they did so, we found little worms and insects.

“We also noted that where dung fell, many kinds of weeds grew up the next year. We did not like this, and carefully cleaned off the dried dung, picking it up by hand and throwing it 10 feet or more beyond the edge of the garden plot.

“We did likewise with the droppings of white men’s cattle, after they were brought to us.

“I do not know that the worms in the manure did any harm to our gardens, but because we thought it bred worms and weeds, we did not like to have any dung on our garden lands and we therefore removed it.”

Horses brought significant changes to the Mandans and Hidatsas, but having them did not change the fundamental organization of the two tribes.

Although horses also gave them greater mobility, the two tribes continued to live in permanent villages. The Mandans and Hidatsas, like the Arikaras who joined them later, incorporated horses into their long-standing traditions.

Gilbert Wilson wrote Buffalo Bird Woman’s Garden after long conversations with Maxidiwiac about the gardens of Hidatsa women.

Buffalo Bird Woman’s Garden: As Recounted by Maxi’diwiac (Buffalo Bird Woman—Waheenee 1839-1932) of the Hidatsa Indian Tribe. Originally published as Agriculture of the Hidatsa Indians: An Indian Interpretation. Edited by Gilbert L Wilson, 1868-1930. http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/buffalo/garden/garden.html#XI

______________________________________________________________________________

NEXT: Blog 74 Happy Holidays—Dec 27

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog

Thank you Francie. We should take note of how they grew their crops! The watching/drying platform is also interesting!