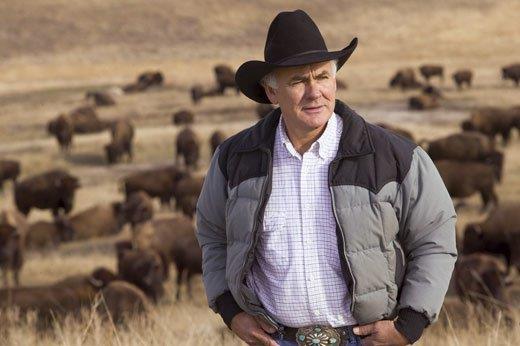

After 30 years building up his herd here in the South Dakota badlands, Frederick DuBray is frustrated. “Everything I try seems to make it worse.” But he is determined to see it through. Photo credit Fred DuBray.

A recent New York Times article by Mitch Smith describes the disaster that has come to one Native American rancher in South Dakota who has worked 30 years to build up his buffalo herd.

He reported that Fred DuBray’s bison herd on the Cheyenne River Reservation has been ravaged by Mycoplasma bovis, a tiny bacterium that is decimating herds across the Plains and the West. Smith’s report He Spent Decades Protecting Buffalo; A Microscopic Invader Threatens That Work appears in the March 12, 2022 issue of the Times.

Since last year, his buffalo have been dying by the dozens, victims of a microscopic invader, Mycoplasma bovis, that has ravaged pastures across the Great Plains and the West, according to Smith.

The reporter describes riding for miles with DuBray through his large buffalo pasture that stretches for miles through the badlands. There he saw for himself black buffalo carcasses scattered in the sprawling pasture—now speckled with skeletons in various stages of decay.

“You have no idea what’s going to happen,” DuBray told him. “I really don’t even know what to do. Everything I try seems to make it worse.”

Now this man, who over the decades has helped lead efforts to re-establish herds on Native American lands, fears that the bacterium is a major problem to the future of the buffalo.

As he drove, DuBray scanned the brushy draws for lone buffalo standing off by themselves. As Smith writes, “There were many. Standing by themselves, or limping or coughing—all signs of an infection.”

DuBray indicated a small group of gaunt bison off to the side—against a riverbank.

“All three of those are sick—this one’s coughing,” he said. “They’re kind of gasping for air. Once they get where they’re like this, their lungs are totally destroyed already.”

“When a calf starts coughing and gasping for air, it’s probably too late—their lungs already may be destroyed,” notes Fred DuBray. SD Game Fish and Parks, Chris Hull.

Gaining Publicity is Worth it

Of course ranchers don’t like to talk about sickness in their herd—especially when they are losing animals. That can trigger one disaster on top of another.

Ranchers who have outbreaks are not required to report them, and many producers fear stigma or financial hardship if they come forward. So obtaining statistics on Mycoplasma deaths has been a challenge.

But DuBray has gone public about his losses and his frustration.

He says his business has already suffered as a result of the outbreak and his openness about it. He expects to stir up more abuse because he speaks publicly about what is happening in his buffalo herd.

But to help the cause is a risk he is willing to take. “People are trying to hush it up—to hide it,” he told me. “But I think it’s too important for that.

“It destroys the lungs, causes respiratory problems. And buffalo are social; they are always trying to lick each other.”

DuBray grew up on a cattle ranch and used to work with the Cheyenne River tribal herd. He says he’ll never go back to raising cattle.

Zach Ducheneaux, the national administrator of the Federal Farm Service Agency and also from the Cheyenne River tribe, said the recent decision to compensate ranchers for their losses should give them a reason to detail their losses, eventually leading to better data about the scale of the problem.

“What’s the point of sharing your information if the door is closed?” asked Ducheneaux, who previously served as a tribal council member at Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation and has worked with DuBray.

“Now that we’ve opened it, I think we can have a freer communication with the buffalo industry about what their numbers are like, what their issues are.”

Both agree that for years the ranchers’ fight against M. bovisWi has been complicated by lack of information about its effect on buffalo.

Ranchers and researchers have relied on anecdotal accounts to come to a consensus that the ongoing surge in cases is probably the worst ever, even as they disagree about whether the bacterium is likely to have dire, species-level consequences.

“There’s just a ton that we don’t know about why this is happening and, therefore, how to manage it,” said Dr. Jennifer Malmberg, a veterinary pathologist from the Wyoming State Veterinary Laboratory who has examined some of Fred DuBray’s buffalo.

Widespread Infection: Causes and Effects

Jeff Martin, who grew up on a Wisconsin buffalo ranch and is now the Research Director at South Dakota State University’s new Center of Excellence for Bison Studies in Rapid City, said there is a link between the growing number of Mycoplasma bovis cases and the warming climate. This can cause stress for buffalo, weakening their immune systems and making them more susceptible to infections.

Dr. Martin has gathered a task force to help find a solution to the M. bovis problem, as they also call it. He said he knows of about 20 bison herds with confirmed Mycoplasma outbreaks in the last 18 months. He adds that it is made worse by drought conditions across the plains.

The Northern Plains, where many of the outbreaks have emerged, have experienced severe drought in recent years.

Many of the known cases in bison have hit private commercial herds, but officials said an outbreak last fall at Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve in Kansas killed about 22 animals, around 25% of their herd.

“This is just one of the expected outcomes of climate change worsening: drought, getting hotter, wildfires,” said Martin. When buffalo are run down or stressed they are also more vulnerable.

“It’s not just that you’re having poor forage quality. You also have poor access [to good water]. As droughts happen, that water begins to dry out and concentrates minerals and salts that are also not good for animals—let alone bison.

“So as they’re having to drink these less quality waters, that just is another compounding factor for their immune function.”

Martin adds what makes Mycoplasma bovis so hard to fight is that it doesn’t have a cell wall, which is what antibiotics target. That’s how most of them work—by destroying the cell wall.

The buffalo is integral to the Lakota Sioux creation story, said Richard Williams, a consultant on Native American issues who is Oglala Lakota and Cheyenne. Lakota people, who for centuries migrated across the Plains with the buffalo and were sustained by its meat, consider the buffalo a relative.

“It’s not just an economic enterprise,” DuBray agrees. “It’s a cultural relationship that I’m trying to restore, as well.

Ongoing Research with Mycoploasma bovis

Dr. Murray Jelinski, a Canadian veterinarian who studies Mycoplasma bovis at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon told the Times:

“When you look at these things under a microscope, they’re kind of a blob—they’re kind of like Jell-O, they sit there—without a firm cell wall. A whole group of antimicrobials don’t work against Mycoplasmas because they don’t have a cell wall.”

Several vaccines tests did not confer protection against M. bovis and even made it worse. Researchers are baffled. The result was post-challenge deaths and increased dissemination of the bacteria.

To learn what NOT to do, researchers might study the National Institute of Health PubMed report Developments in Vaccines caused by Mycoplasma bovis, published June 9, 2021.

I hope they are challenged—not discouraged—by its conclusion:

“Several vaccine tests did not confer protection against M. bovis and even made it worse. The result was post-challenge deaths and increased dissemination of the bacteria in the host.

“To some extent, the vaccine partially reduced M. bovis joint colonization. However, it did not protect against the M. bovis spreading from the inoculated to non-inoculated joints, which was observed in both examined groups of calves.

“Inactivated vaccines are the most commonly used in studies to prevent infections with M. bovis. However, it is generally considered that inactivated vaccines have some disadvantages, including high production costs as well as possible modifications of the proteins of the strains during subculture.

The PubMed article reviews a number of attempts at developing vaccines.

“Many studies have been done using experimental vaccines but to date commercially available vaccines are available only in the US and their efficacy is not fully satisfactory.

“Contagious bovine pleuropneumonia (CBPP), one of the great historic plagues of cattle alongside the now eradicated rinderpest, continues to inflict serious losses on livestock in many parts of sub-Saharan Africa.

“But why is CBPP continuing to cause problems when it has been eradicated from Europe, Australia, Asia and North America?

“Sadly, because of economic hardships, civil wars and droughts affecting the countries where the disease is endemic and the inability to prevent transboundary movement of livestock, control in Africa seems further away than ever. CBPP is a severe pneumonia of cattle caused by the wall-less bacterium Mycoplasma mycoides subspecies mycoides.

“The disease is localized in the lungs, where it causes a highly characteristic ‘marbling’ of the lungs in the acute stages and lesions known as a ‘sequestra’ in the chronic form of the disease, according to the government publication PubMed.

Clinical signs include rapid breathing, fever, nasal discharge, anorexia, cough on exertion and sudden death. Mortality rates can exceed 50% when the disease appears for the first time in herds.

The difficulty is identifying affected animals quickly enough to prevent the disease spreading because, though the lung may be very severely damaged, clinical signs are often lacking.

“Inactivated vaccines are the most commonly used in studies to prevent infections with M. bovis. However, it is generally considered that inactivated vaccines have some disadvantages

“Clearly, next generation vaccines to replace T1/44, should, ideally, be stable, given in a single dose, provide a longer duration of immunity and higher levels of protection and not cause adverse reactions.”

“A vaccine that would confer better immunity is urgently needed. What is clear, is that any M. bovis vaccine needs to be part of a wider vaccination program involving other respiratory pathogens,” NIH researchers say.

As stated prophetically by researchers in 2004: “this is by no means assured.” Indeed, since then no vaccines to date have met all these criteria. Despite encouraging immune responses, cattle, given an immune-stimulating complex (ISCOM) vaccine, had similar gross pathological and histopathological scores as non-vaccinated controls.

“In spite of two vaccinations at 6-weekly intervals and high antibody responses there was no evidence in the animals used of any protection afforded by either preparation; indeed, there appeared to be an exacerbation of pathology in the vaccinated animals compared to unvaccinated contact controls.

“Lesions and fibrin were most extensive and pleural fluid more abundant in vaccinated animals. In one group, half the cattle died before the end of the experiment, while a quarter died in the other group, compared to just under half that died in the control group.

“Data on the present commercial vaccines in use today are modest at best, with one showing an efficacy of 1%. Clearly, improvements need to be made before control of this fast-emerging disease is possible.”

Another vaccine did not protect against the effects of articular challenge with the virulent M. bovis strain, despite effective stimulation of the humoral response. Post-challenge, the clinical disease and the joint lesions in the vaccinated calves were similar to those observed in the non-vaccinates, which was additionally confirmed by histopathology.

The PubMed report continued, “The countries with the highest prevalence include Ethiopia, Ghana, Tanzania and Angola. Indeed, this has hardly changed over the last 20 years, showing that most attempts at control have been unsuccessful.

“The disease in sub-Saharan Africa is mostly characterized by occasional severe outbreaks when native herds are exposed to infected animals moved often illegally across borders. Moreover, due to the weak economies of many countries, stamping out the movement control, slaughter and compensation seen in Europe are not options.

“A Scientific Conference in Gaborone in 1994 concluded that vaccination of cattle remained the best way of controlling CBPP, but a vaccine that would confer better immunity than the T1 strain vaccine being used was urgently needed. Over a quarter of a century later, scientists came to the same conclusion.

“Calls for studies into the immunology of the diseases have also failed to provide sufficient insight to improve vaccines. No inactivated, sub-unit or attenuated vaccines have been developed which improve upon the live TI vaccine developed in the 1950s.

“The limitations of the T1 strain vaccine have been long recognized: short duration of immunity and tendency to cause adverse reactions, and because it is only semi-attenuated, it can lead to outbreaks in closed herds.

“Mass vaccination had been highly successful in many countries but failed in others due mainly to the inability to maintain annual vaccination.

“What is clear, however, is that any M. bovis vaccine needs to be part of a wider vaccination program involving other respiratory pathogens, including BVD, PI3V, Mannheimia, Pasteurella and possibly others.”

New Resources on the Way

“We are excited to assist the bison industry in this way,” says Martin, who is officially in charge of bison research in the US—as Director of the Center for Excellence for Bison. “We look forward to contributing in such a large and positive way that identifies some relief for bison managers while research advances to discover more effective vaccines and treatments.” He can be contacted at SDSU (605-688-4792) or email sdsu.extension@sdstate.edu.

Jim Matheson, now Director of the National Bison Association, located in Colorado—moving up from his position after many years as Assistant Director—tells me NBA will shortly have a one-page handout on M. bovis and what producers should watch for so they might relieve stress on bison and other problems at an early stage. www.bisoncentral.com

A world-wide problem, Mycoplasma bovis was first isolated in the US in 1961 from the milk of a cow with mastitis. It is one of 126 species of genus Mycoplasma, and the smallest living cell in nature.

It causes many diseases including mastitis in dairy cows, arthritis in cows and calves, likely late-term abortion and various other diseases. Mostly the M. bovis affects cattle, but except for calves not as fatally as it does bison.

Seemingly buffalo have no natural immunity against its devastating ravages. There’s no effective vaccine or treatment for M. bovis infections.

We may think that should be easy to solve. But the experts know better.

As of June 2017, only two OECD nations (an international economic organization of 34 countries, founded in 1961 to stimulate economic progress and world trade were considered to be free of Mycoplasma bovis. They are New Zealand and Norway, but in July 2017 some cattle near Oamaru, New Zealand were found to be positive; see 2017 Mycoplasma bovis outbreak.

Qualifying for FSA Indemnity Program

Dark buffalo carcasses were scattered over Fred DuBray’s big pasture—skeletons in various stages of decay. Photo NPS.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture Farm Service Agency (FSA) recently announced that bison death losses resulting from Mycoplasma bovis are eligible for the livestock indemnity program that reimburses ranchers to some extent. Authored by Jeff Martin, it is retroactive to cover loses in 2021.

Ducheneaux urges: “For now, please encourage any of your producers to notify their local FSA office of any and all losses as soon as possible and keep them updated as to further losses they may sustain and ask for an ELAP application.”

Also, if there is overlap of Mycoplasma losses with drought, the USDA requests that weather be documented as well to assist with decisions. Drought conditions for your area over the past year can be determined using the comparison Drought Monitor online tool.

Ironically, the most urgent recommendations in Martin’s article on M. bovis is how to dispose of infected carcasses. Financial assistance is available under the name Emergency Animal Morality Management as part of Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP).

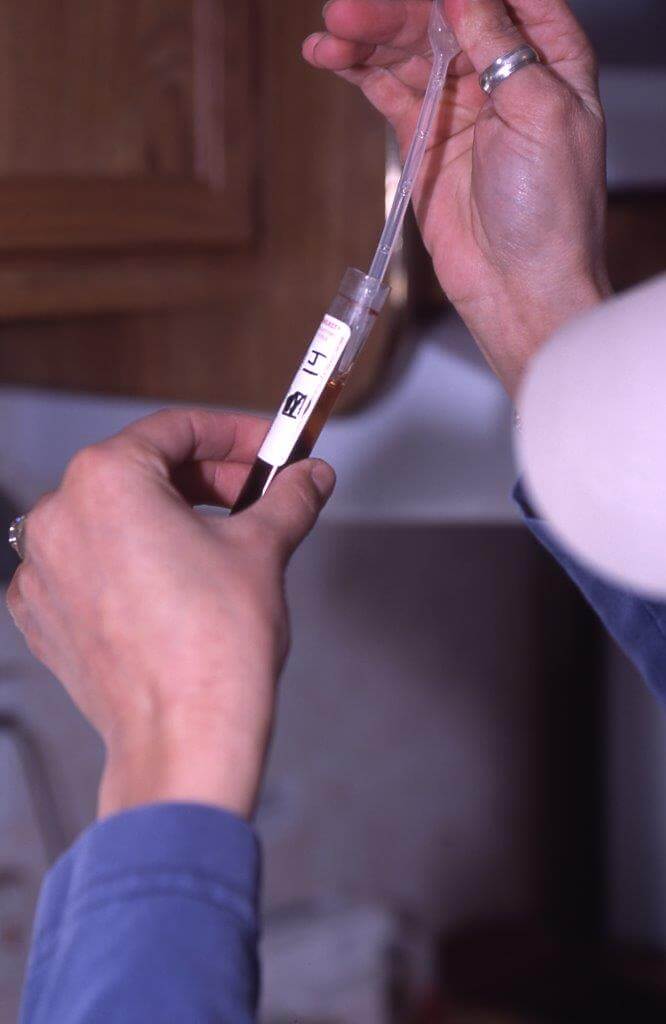

Agricultural producers and owners of nonindustrial private forestland and Tribes are eligible to apply for EQIP funds. To receive assistance, papers must be filed and approved before disposal of animal carcasses. Before payment, a mortality certification is required by a veterinarian or an animal health specialist.

Qualifying losses include those greater than 5% in young bison under 400 lbs and/or greater than 1.5% in mature bison larger than 400 lbs. Acceptable proof must be provided as follows:

- Of a beginning inventory prior to infection that year and a final tally of deaths by four categories: Bison less than 400 lbs. (broken down by males and females) and bison greater than 400 lbs. (broken down by males and females).

- That your property experienced adverse weather event(s) within a reasonable timeframe before the bison died, including, but not limited to, extreme cold, oscillating temperatures and/or precipitation and/or drought;

- Your local veterinarian’s certification of death loss attributed to Mycoplasma bovis. This may include, but is not limited to, a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test of at least one animal to confirm that Mycoplasma bovis was present in the individual and that symptoms were present in the remaining individuals. The FSA allows euthanasia of animals suffering from symptoms of Mycoplasma bovis, but the diagnosis must be verified by a veterinarian.

“We need to know more about Mycoplasma bovis. The manner of development of this disease in bison. We also need a well-designed and systematic scientific study of the distribution, frequency, patterns and risk factors for bison,” says Dr Woerner, Montana Veterinarian.

Prevention for Now

Dr Don Woerner, a veterinarian friend of mine from Laurel Montana visited Fred Dubray’s ranch and observed his wide-open South Dakota badlands pastures where there’s plenty of freedom for the buffalo.

“We need to know more about Mycoplasma bovis,” Woerner says. “The manner of development of this disease in bison. We also need a well-designed and systematic scientific study of the distribution, frequency, patterns and risk factors for bison. How it acts. Bison don’t have immunity to this.

It is unclear whether research underway can come in time to help Fred DuBray, whose herd continues to dwindle. Photo Chris Hull SD GFP.

“Feeding low-level antibiotics to our domestic livestock and poultry has never been a good practice and the fact we are getting all these strains of M. bovis may be a result of it.

“I like to see bison managed like a wild herd. Not using antibiotics for buffalo—that can cause complications. These organisms mutate and change.

“I don’t really like bringing buffalo together for sales or competition—and then taking them back home again after they’ve been with other animals.

“We need to quarantine them in a good facility before putting them back in the herd. Some say for 30 days; I prefer 45 to 60 days. Bio security is important—we need to be aware of it.

“We have to be able to deal with buffalo as they are. Sometimes its hard: bison have evolved without the help of man. What’s a good animal? Some have genetic issues.

“We should not manage buffalo with a ‘cattle mentality.’ Bison should be celebrated and managed as the wild animal they truly are.”

Dr. Danielle Buttke, a veterinary epidemiologist with the National Park Service who also has visited the DuBray ranch to study the deaths, said that the limited buffalo gene pool, a legacy of the large-scale slaughter during westward expansion, has made it harder for the species to withstand disease outbreaks.

“Without urgent action, Mycoplasma threatens to undo much of the painstaking conservation work that has stabilized buffalo herds.

“It’s not just the loss of individual animals,” Dr. Buttke added. “It’s a very, very different impact to a species that already suffers from genetic bottlenecking and isolation than it is in a cattle system.”

Dr. Buttke said she was working to develop a better test to detect buffalo carrying the bacterium without showing symptoms, which would allow ranchers to isolate those animals before they could spread Mycoplasma widely. She worries about mutations, about species-to-species transmission, about the challenge of developing treatments.

It was not clear that any of the research would come in time to help Fred DuBray and his wife, Michelle Fredericks DuBray, whose animals continue to suffer and whose herd continues to dwindle, according to the Times article.

“The ones that are surviving are they going to be OK?” asked Michelle DuBray. “Are they going to get this next year? Do we keep the calves? What do we do?”

###

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog

Thanks for your great research and writing.

Don “Doc” Woerner, DVM

Laurel East Animal Center

Field Museum of the American Buffalo

Laurel, Montana