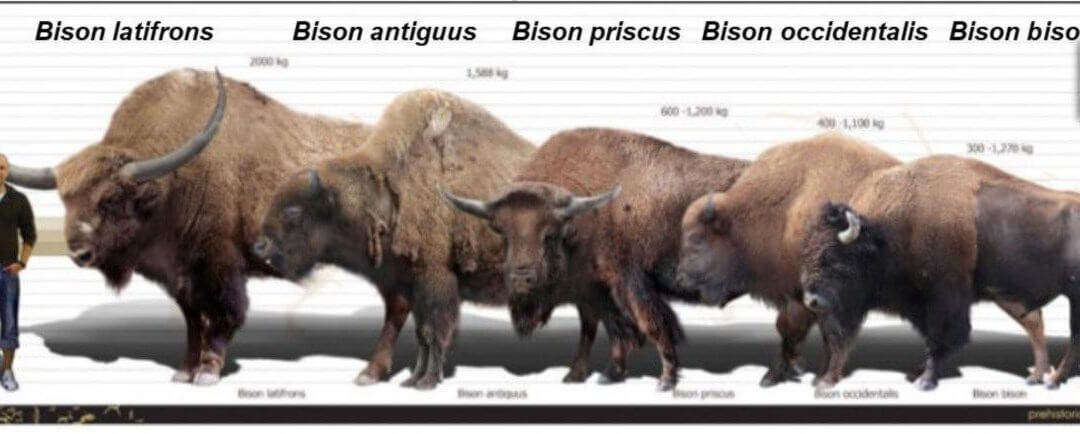

The Incredible Shrinking Buffalo

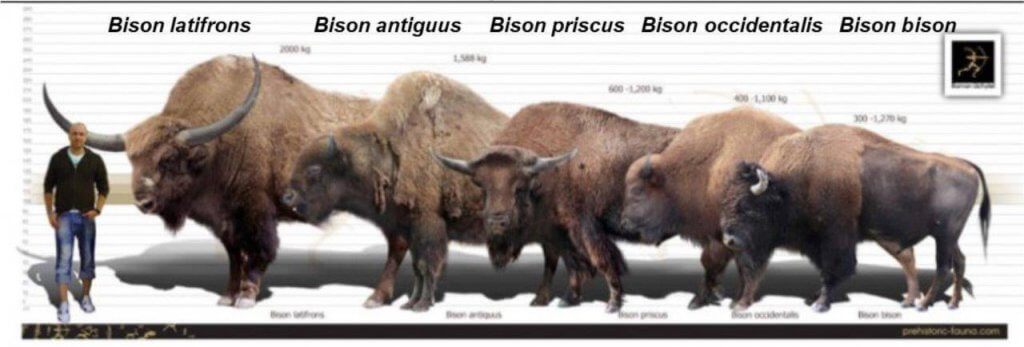

Ancient Bison in North Dakota include Bison latifrons, a giant buffalo with long and only-slightly curved horns now extinct, at left, and decreasing-size species that once lived in the western US. Only the smallest of them all—the Bison bison, at right, survives today. They exist in two subspecies: Bison bison bison of the plains and Bison bison athabascae of the far north.

The small party of Native American hunters were excited when they discovered a herd of bison grazing on open high prairie near some large hills connected by a steep ridge.

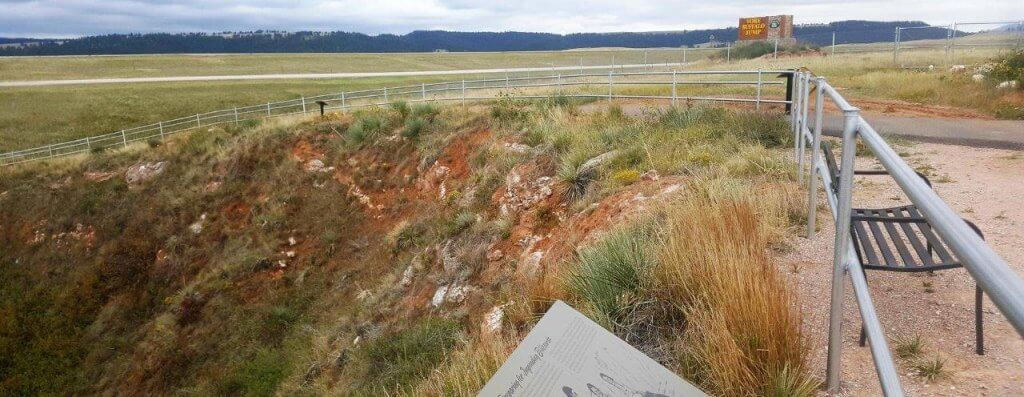

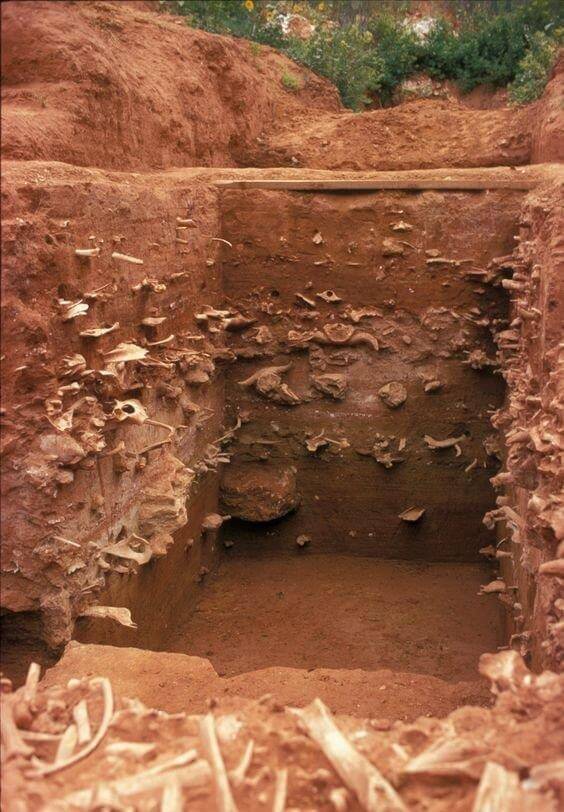

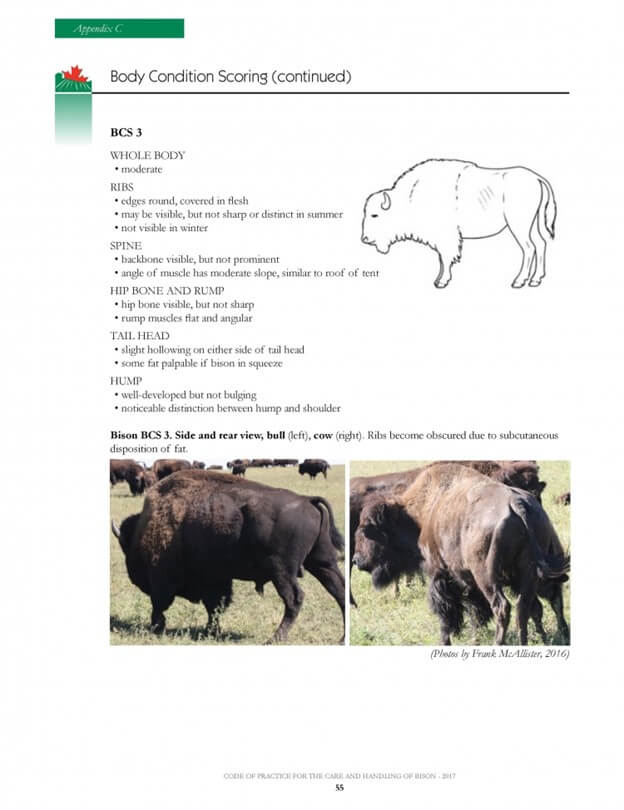

The experienced and opportunistic hunters quickly noted that the terrain favored them. Several arroyos, perhaps 30 feet deep and a hundred feet wide at their mouths, cut into the crumbly red sedimentary siltstone that formed the base of one hill.

These erosion features looked like possible escape routes to the bison, but their channels narrowed quickly so that they essentially became small box canyons.

The hunters recognized that, if they were to drive their prey into the gullies, the walls would be too steep for the bison to climb and the animals would have no room to maneuver.

The hunters could then get close enough to the large beasts and dispatch them with atlatl darts while standing safely on the rim of the arroyo.

The Indians executed their plan, killed a number of bison and butchered them where they lay.

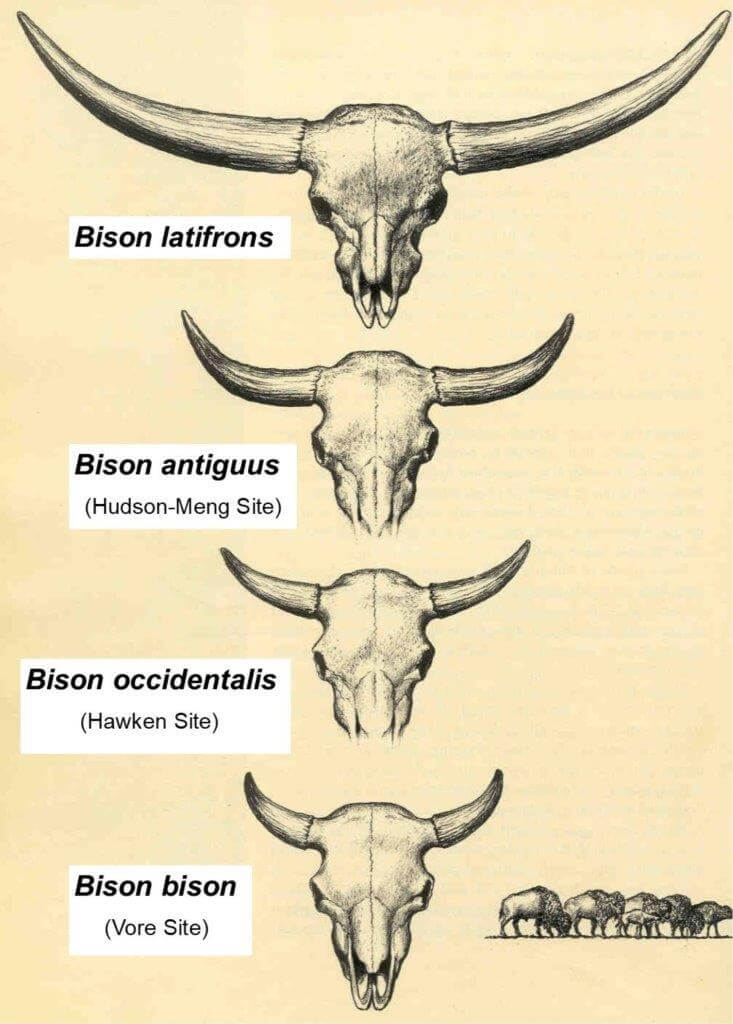

Comparative skulls of North American bison.

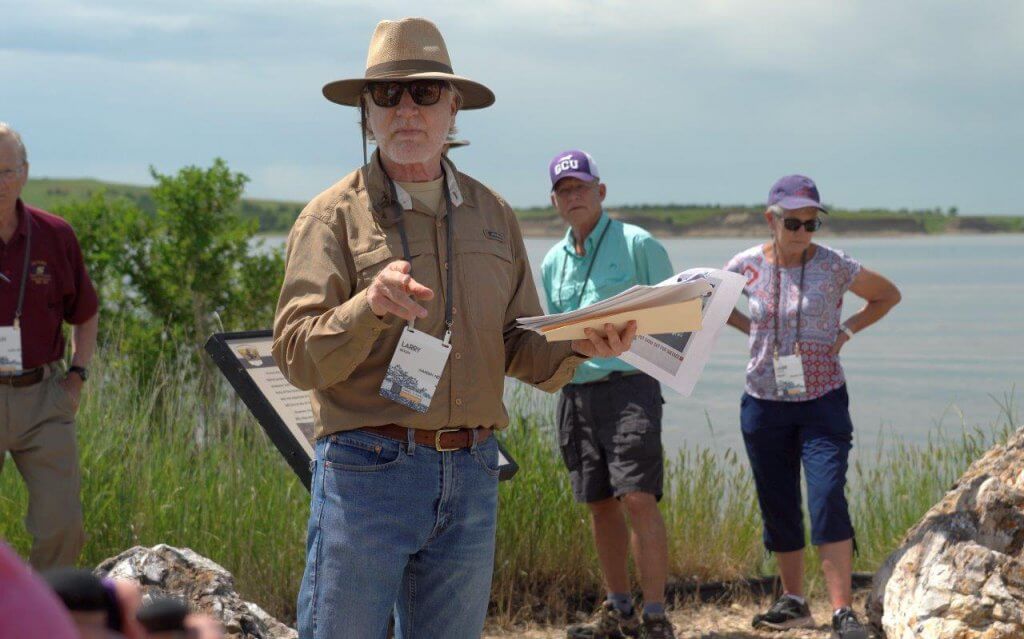

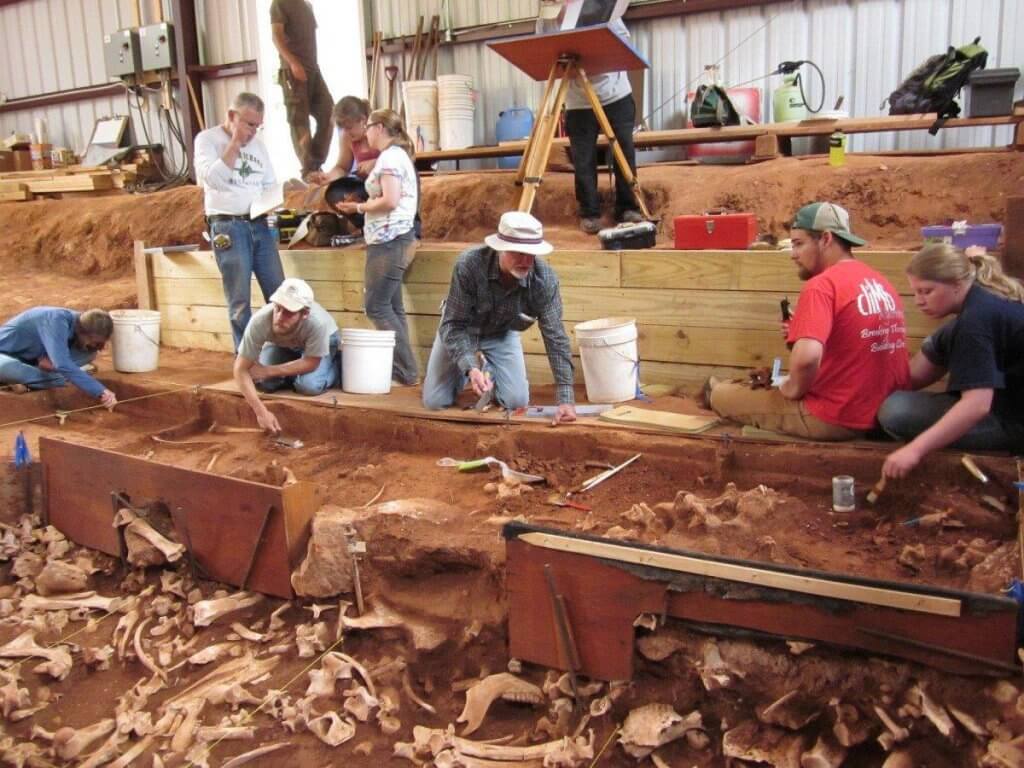

The bones and projectile points were soon covered by mud and remained there for six thousand years until a cowboy discovered some of them protruding from the walls of the arroyo.

The find was reported and was subsequently excavated by famed archaeologist George Frison and his crew from the University of Wyoming.

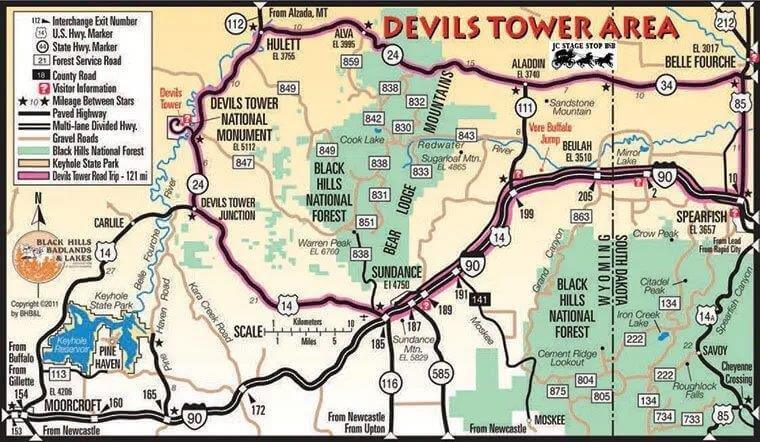

The find was named the Hawken Site after the owner of the ranch on which it was located, about 25 miles west-southwest of the Vore Buffalo Jump.

It proved to be one of the most important sites for the period it represented, the so-called Mid-Holocene Warm Period (a.k.a. “altithermal”).

The buffalo killed were of a species named Bison occidentalis that would become extinct fairly soon after the Hawken hunt.

B. occidentalis was one of several bison species that died out, leaving only Bison bison, often called buffalo, in North America.

The Bison Family Tree

Bison latifrons—An extinct giant buffalo.

The ancestors of modern bison appeared in Asia about two million years ago. They roamed the “steppe,” a vast, flat, grassland that stretched across southeastern Europe and much of Siberia at the same time as the progenitors of mammoths.

Steppe Bison—Ancestor of all North American bison species.

Steppe Bison shared the Old World with several other bovine species, including the Aurochs Steppe Bison—Ancestor of all North American bison species that gave rise to modern domestic cattle and several species of Asian and European bison.

During the last Ice Age, so much of earth’s water was tied up in glaciers that sea level was almost 300 feet lower than it is now.

Many continental shelf areas currently covered by shallow saltwater were exposed and became land between 240,000 and 220,00 years ago.

One such region was the seafloor between Siberia and the Seward Peninsula of modern Alaska. Falling sea levels there resulted in a land bridge that connected Asia with North America.

Animals were able to move both directions over this neck of land. Among other species, bison, mammoths, wolves and, later, humans and their dogs found their way into the Western Hemisphere.

Horses and camels moved the opposite direction, evolving in the New World but finding new homes in Eurasia. Horses evolved in North America but died out here after they crossed the land bridge and established themselves on the Eurasian steppe.

Horses were eventually domesticated and returned to their birth-continent with the Spanish Conquistadors in the early 1500’s.

The bison family tree branched after it was established in North America. The Steppe Bison is thought to be the ancestor of three now-extinct bison species, and eventually, the modern buffalo. The extinct species were all larger than the today’s bison.

The largest individuals of B. latifrons had a shoulder height of 8.2 feet and weighed as much as 4,400 pounds (25% to 50% larger than biggest modern buffalo). Some individuals possessed relatively straight horns more than three times longer from tip to tip than today’s bison.

B. latifrons lived in the warmer middle of North America grazing the grasslands and browsing in the forest. It became extinct between 21,000 and 30,000 years ago

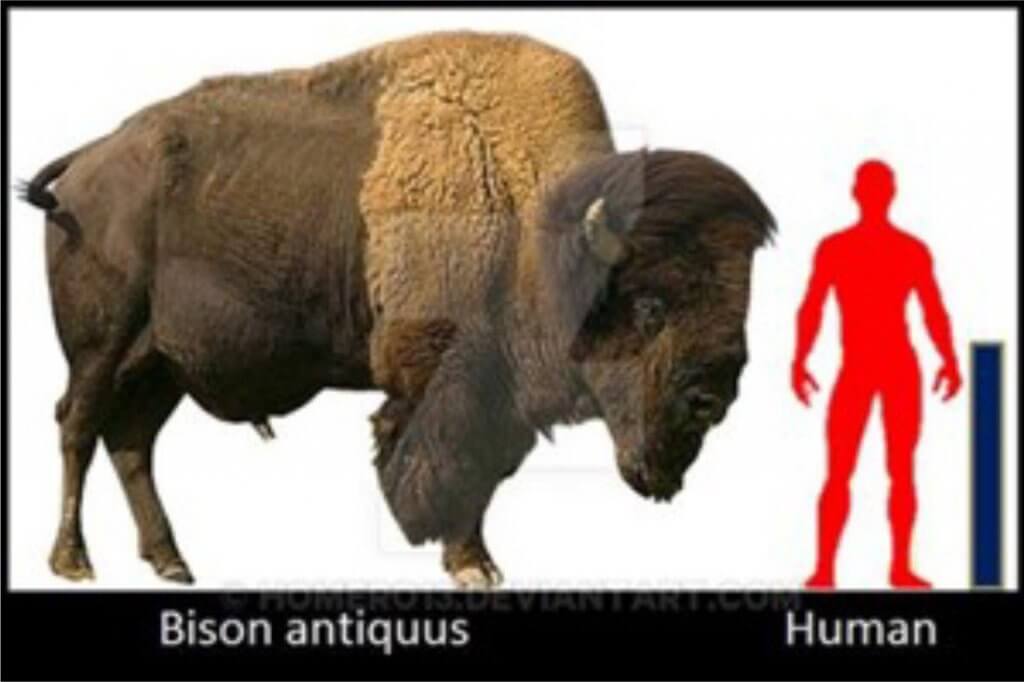

Bison antiquus — One of the “megafauna”

A second species, Bison antiquus, is thought to have evolved from B. latifrons.

B. antiquus was still massive (7 ½ feet and 3,500 pounds) with a more pronounced hump and less bulky hind quarters. Its curved horns also measured 3 feet from tip to tip.

They also lived in the midcontinent but were extinct by about 10,000 years ago along with many other species of the so-called megafauna (including saber-tooth cats, dire wolves, short-faced bears, mammoths and giant sloths).

There is much conjecture about the possible role of human hunting in these extinctions. Most likely these species were already stressed and declining because of changes in climate and ecology, but hunting by Native American was probably a factor in the extinctions.

The Hudson Meng Site managed by the US Forest Service on the south end of the Black Hills (20 miles northwest of Crawford, Nebraska) is an excellent place to see B. antiquus bones.

It is a large kill site apparently the work of Indians of the Alberta and Eden cultural complex.

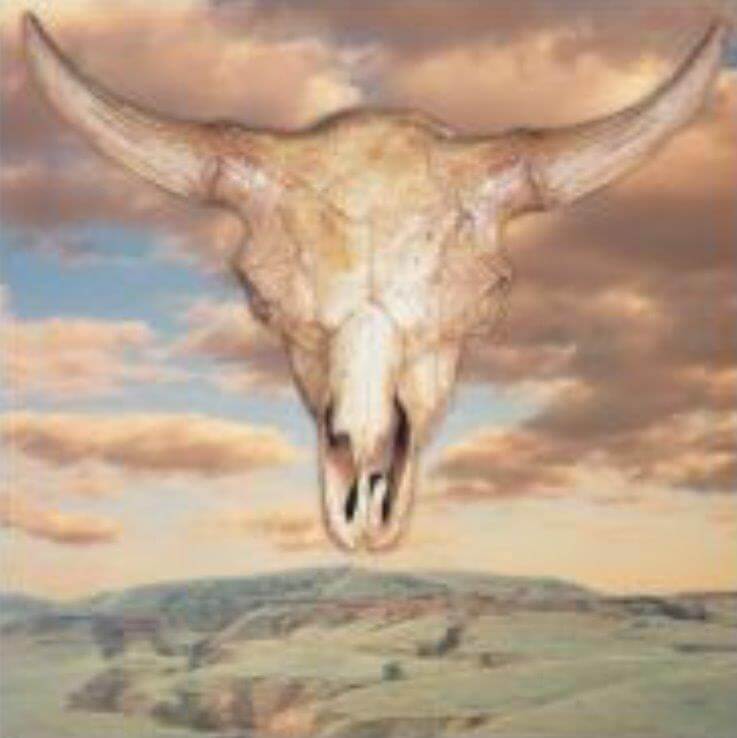

A poster of a Bison occidentalis skull from the Hawken Site imposed over a photo of the Wyoming arroyo where it was killed 6,000 years ago.

B. occidentalis became extinct near the end of Mid Holocene Warm Period about 5,000 years ago, but not before it gave rise to the modern Bison bison (6 feet tall and 2,000 pounds).

The abnormally warm period lasted from about 7,000 to 5,000 years ago and is thought to have been caused by slow and minute changes in the earth’s orbit.

During this time, the Northern Hemisphere was both warmer in summer and colder in winter than at present.

The result was that the Great Plains were drier and produced less forage for grazing animals like bison than it does now.

Lower elevation regions shifted toward desert-like conditions during the Mid-Holocene.

Populations of both prey animals and humans fell. Animals were attracted to higher elevation ranges such as the Black Hills and Bighorn Mountains, which were cooler with more precipitation.

There are fewer archaeological sites from the period, and most of them have been found at higher elevations.

That may explain why the B. occidentalis killed at the Hawken Site and the B. antiquss at Hudson-Meng were near the well-watered Black Hills.

(Another buffalo jump was partially excavated last summer on a ranch a few miles east of the Vore Site. The bison skulls found there appear to be B. occidentalis, though definitive carbon dates on the specimens are still pending.)

In any case, the more extreme conditions were probably a factor in the extinction of B. antiquss and B. occidentalis, and their replacement by the two subspecies of buffalo we know today.

The extant subspecies are the familiar Plains Buffalo (Bison bison subspecies bison) and the somewhat larger Wood Buffalo (Bison bison subspecies athabascae).

The latter live in or near the boreal forest in Canada. There are some differences in body form, behavior, habitat and forage preferences between them.

Their current ranges are separated by considerable distances. However, the subspecies can crossbreed and produce viable offspring.

Plains Buffalo (Bison bison bison) grazing near Hettinger, ND, with their newborn cinnamon-colored calves in July 2022. Photo Credit Kathy Berg Walsh.

In fact, in the desperate days when modern bison were hanging by a thread over the abyss of extinction, bison from the Plains [may have been] interbred with somewhat larger Mountain Buffalo that hung on in Yellowstone.

All of the buffalo killed at the Vore Site were Plains Buffalo, and the period in which the Vore Site hunts occurred was a colder, wetter time called the Little Ice Age.

Nature is dynamic. Change is constant. Living things must adapt or become extinct.

As the post-glacial period brought drier conditions to their primary habitat, bison adapted genetically by reducing their body size and, thus, their forage requirement.

Anyone who has spent time observing buffalo at close range is likely to be impressed by their size, power, speed, agility and general toughness. They are large, often unpredictable and potentially dangerous wild animals.

Modern bison are smaller than their extinct predecessors, but their population increased dramatically after the Holocene Warm Period.

Before the intentional destruction of the great herds in the 1800’s, there were, conservatively, thirty to forty million buffalo on the Great Plains.

In that environment, buffalo were so well adapted and abundant that the Native Americans of the region built their entire cultures around the great beasts.

Guest Article by Gene Gade. As the County Extension Agent in Sundance Wyoming, Gene Gade served 20 years as president of the non-profit Vore Buffalo Jump Foundation, helping to develop and guide the research, education and economic potentials of the Vore site until his retirement. He continues to write for the VBJF Newsletter. Now in Oregon where he and his wife moved to help a daughter with their grandchildren, Gade volunteers in working for Native American causes. It’s a new vantage point for him, he writes, “The devastation of the Columbia River salmon has been as disastrous to Indigenous people of the northwest as the near extinction of bison was to the Plains tribes.”

Reprinted from the VBJF Newsletter with permission: Vore Buffalo Jump Foundation, 369 Old US 14, Sundance WY 82729; Tel: (307) 266-9530, email: <info@vorebuffalojump.org>